|

A mother’s mission to fight the Catholic Church and find justice for her son

By Jeremy Rogalski And Tina Macias

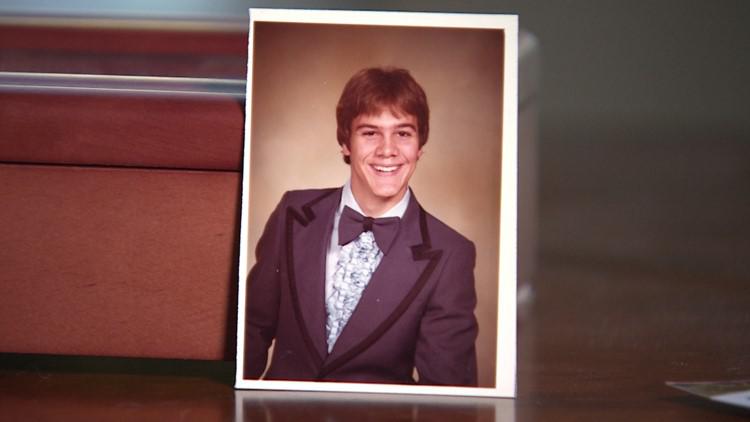

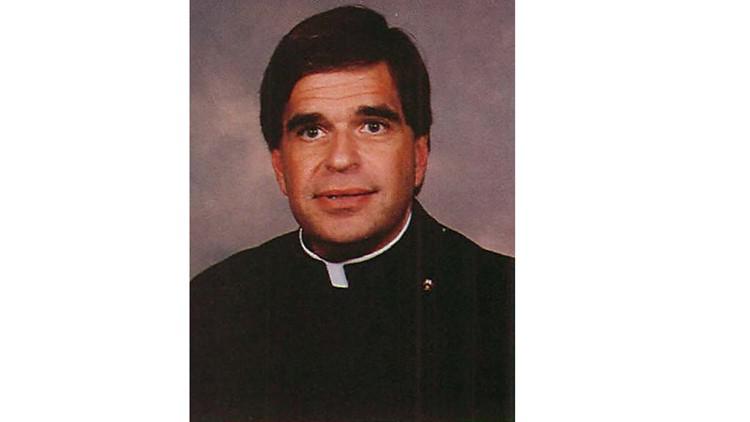

[with video] [with pdf] With the sun dipping below the trees on a late November afternoon, Carol LaBonte stood outside the black wrought-iron gates of Prince of Peace Catholic Church in Spring with a sign that read “Jesus Weeps.” Although her seven children left the nest decades ago, she still finds herself protecting them. That’s what she was doing on this afternoon, joined by a group of others gathered outside the church with signs reading “Your pastor has secrets” and “Protect children not abusers.” “It’s been all these years that the truth has not come out,” LaBonte said, now silver-haired and a cane resting by her side. “The pastor is still the pastor and abuser of my son.” The priest, Rev. John Keller, has been at Prince of Peace for nearly 20 years. But there was a time in the mid-1980s he was the associate pastor at another church just a few miles away, Christ the Good Shepherd, where the LaBontes were parishioners and heavily involved in the church. LaBonte’s late husband, Stephen, was a deacon. A change in her sonTheir teenage son, John, was especially pious, spending his time doing odd jobs at the church — yardwork, cleaning and working at the desk. He aspired to be a priest, and even spent three summers at a seminary program for teenagers interested in joining the ministry. “He used to sign his letters, his cards to us, Mother’s Day cards, ‘In Christ’s love,’” LaBonte said. “He was very spiritual.” But LaBonte noticed a change in her son shortly after he took a trip out of the county with Keller. In the months after, she discovered books about suicide on his desk and later found two letters from Keller. “Talking about, ‘I know you were upset about what happened. I’m so sorry that you were hurt. It isn’t my intention. Please don’t blame God. I really love you. I love you so much.’ And, ‘I love you, I love you,’ repeated in both of the letters,” LaBonte said. “I felt sick to my stomach. … I just couldn’t believe that a friend — a priest — would do something. And I knew something terrible had happened.” She said her son later told her Keller gave him wine and groped him by putting his hands in his pants. But at the time, he downplayed the abuse, only saying Keller “talked about how lonely he was and asked him into his bed.” Livid, LaBonte confronted Keller. Years later, the archdiocese and Keller would say he acted inappropriately, but did not abuse John. But when he was confronted by Carol LaBonte in the ‘80s, she said he was nervous and anxious but didn’t deny her accusations. “He didn’t say what had happened, but he didn’t say, ‘What are you talking about?’ He didn’t say, ‘I don’t know what you mean?’ He didn’t say, ‘Nothing happened.’ He didn’t say any of that,” LaBonte said. She told him to leave her family alone and seek therapy. She said Keller reassured her that he was getting help. Her husband Stephen wrote a letter to then-Bishop Joseph Fiorenza, who at the time oversaw the Diocese of Galveston-Houston, warning him of a predator priest. “We were so naïve at the time, thinking, ‘You don’t tell someone else’s sin, you don’t call scandal to the church. We’ll give it to the bishop; he’ll know what to do,’” LaBonte said. But LaBonte said the letter went unanswered. “And I was stupid enough to let it go,” LaBonte said. “I wish we called the police. … I can’t even have imagined doing that at the time … I suppose because we had trusted the church.” It was the 1980s and the thought of a priest abusing a child was unfathomable. At the time, only a few accusations were public. RevelationsThen in 2002, a ground-breaking investigation by The Boston Globe uncovered a systemic issue of clergy sex abuse in the Greater Boston area. The LaBontes realized they were not alone. “This wasn’t a one-time thing that happened to our son by a priest. This was pervasive within the church,” she said. “Clergy abuse was all over.” The revelation led Stephen LaBonte to again report the allegations to the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston with their son’s permission. The National Conference of Catholic Bishops had just adopted the “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People,” commonly known as the Dallas charter, which outlined how to address sex abuse allegations. The charter required dioceses to form review boards made up of mostly lay people. The boards assessed allegations and made recommendations to the bishop. The archdiocese added another layer to that, creating a special panel of three to five people, including at least one priest. That panel was tasked with interviewing the victim, the accused and witnesses and preparing a written report for the review board. LaBonte’s son was asked to speak in front of the newly formed group. His dad worried that going into a building full of priests would bring back the trauma “and he’s going to be right back to being 15,” LaBonte said. But their son, now an adult, declined his dad’s request to go with him to the Chancery, telling him, “No, dad, I can handle it,” LaBonte said. That review board determined Keller “acted very inappropriately” but could not conclude that it “constituted sexual abuse,” Fiorenza wrote in a 2003 letter to John LaBonte. “Father Keller has acknowledged that he crossed a proper boundary by holding you in a manner inappropriate for a priest. However, he denies any sexual intent or abuse in his conduct with you,” the letter read. Keller was assigned to Prince of Peace in 1999 and remained there through the process, according to archdiocesan directories. He’s still the pastor today. The archdiocese said in a statement that John LaBonte’s accusation is the only one they’ve received against Keller. Even today, LaBonte’s delicate purple glasses fog with anger when she reads the letter. “He crossed a boundary he shouldn’t have, but, yet, it’s not sexual abuse? It’s called bullshit,” she said. ‘I won’t keep the secret’Labonte feels the pain again every time a new sex abuse scandal surfaces, especially when she learns that Keller often addresses his congregation during those times. “Just recently, Keller stood up again and said … ‘A long time ago I was accused of sexual abuse, but they found that I was innocent. I had to learn that you have to be careful about hugs,” LaBonte said, as she shook her head and let out a sardonic sigh. Even with her exasperation, she said she’s forgiven Keller. “I see Keller as wounded, I see that as an illness,” LaBonte said. Forgiving the church, “that’s harder,” she said, her voice cracking. “What they do is make it capable for sick people to continue … to hurt children,” she said. “You certainly don’t put them in charge of children. You certainly don’t say, ‘It’s OK for you to wear the collar that says I represent Christ.’” She hopes to see Keller’s name on the list of credibly accused priests the archdiocese said it will release by the end of the month, though she has her doubts. “I don’t have a lot of hope,” LaBonte said. “I won’t keep the secret. Whether they will or not, I don’t know.” Sometimes she feels she helped keep that secret, feeling her inaction in the 1980s protected the church instead of her son. Her son, John, now lives out of state with his wife. He still sees a therapist. LaBonte still wishes she would have done more to protect him back then. “Whenever any of your children are hurt, you’re hurt,” she said. “When they’re hurt in their soul, when they’re hurt like this, it’s too much. I haven’t done my job.” But she won’t stop fighting for him now. Even if that means standing outside the black wrought-iron gates of Prince of Peace Catholic Church as the sun dips beneath the trees, standing for her truth. “I still have hope that the Catholic Church can be what it’s supposed to be,” she said, “but it can’t be if the truth isn’t out.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.