|

Sisters’ plea to the Catholic Church: ‘I want the truth to be known’

By Jeremy Rogalski And Tina Macias

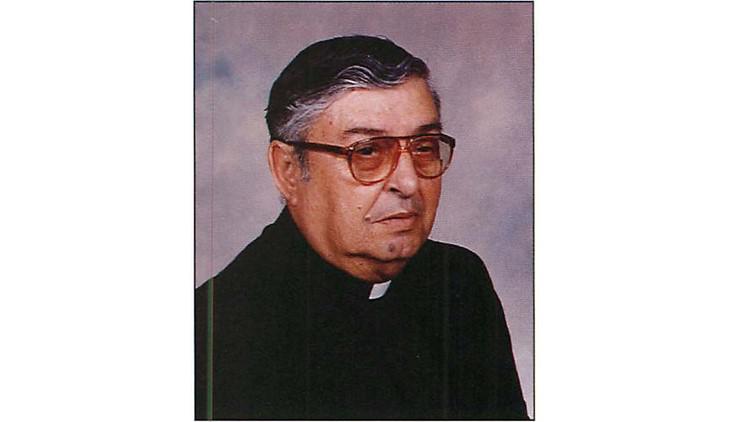

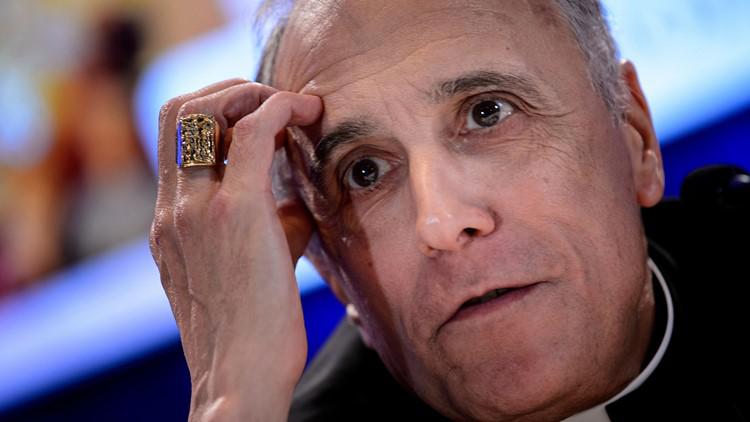

[with video] This story is part of KHOU 11 Investigates' series “Unforgivable.” Parts may contain graphic descriptions of sexual assault. If you or a loved one have experienced sexual abuse, get help through the free and confidential National Sexual Assault Hotline (1-800-656-HOPE). There was a time when Monica Deanda Baez was a little girl that she prayed to God to let her die. In her family’s modest home in northeast Houston, she would climb on top of the toilet and scream out the bathroom window to God, to whomever — to whatever — would listen. “I would beg God,” Baez said. “Please let me die, ‘cause I don’t want him to do this to me anymore.” Baez, now 53, said for years she was sexually abused by her family’s priest. It was only later she learned that her older sister, Elodia Flores, and three of their siblings also said they suffered the same abuse by the same priest. Their priest at Our Lady of St. John Catholic Church in the 1960s and 70s, Rev. Lawrence Peguero, would drop in on the family, the sisters said. It’s something that is usually an honor for a deeply religious family. “It was just like you had Jesus come over,” Flores said. “He was a holy man.” Their mother often reminded them about the importance of the Catholic Church, telling them, “We were poor people and religion was the only thing that we had left to give our children,” Baez said. Baez said she remembers Peguero arriving unannounced at their home when the other children went to school, and she was alone with her mother. “He would ask for tortillas or whatever breakfast he wanted, something he knew she made from scratch always — and if it was for a priest, she was going to do her best to make whatever meal he wanted,” Baez said. While her mom cooked, Baez said Peguero would take her into another room, just on the other side of a curtain and rape her, sometimes under the guise of taking confession. It didn’t matter if she was too young for confession. “He would get me forcefully, and he would pray out loud while he would try to penetrate (me),” Baez said. “There’s a curtain in between that’s closed … but he’s praying out loud, so my mother is hearing the praying.” She would struggle and fight but said Peguero would cover her face and pray loudly to muffle the sound. She said the abuse went on for years. ‘He was my monster’Before Baez, Flores said Peguero raped her. “Since I was 4 or 5, all the way ‘till age 11,” she said. “He was my monster.” She can’t help but question: What did a grown man want with a 4-year-old girl? “He would grab me,” Flores said, now 60. “He would get me, put me on his lap, ‘Oh let’s ride the horse,’ and the whole time he was just dripping with sweat. He was just grabbing me. He was grabbing my breasts, which I didn’t have any, just squeezing me tight, and I felt like I was going to break.” Fear was compounded when, during the assaults, Baez and Flores said Peguero whispered threats and telling them that no one would believe them if they told. “’You tell anybody you’re a liar. You’re a nasty, dirty little girl and your daddy is not going to love you,’” Flores said Peguero told her. “You know, ‘Don’t tell your mom. … I’m going to kill them, I’m going to kill your baby sisters.’ What are you supposed to do? You believe him.” The threats were similar for Baez, who said Peguero would whisper to her, “You don’t want your mother to go to hell, do you?” The intimidation always came when she struggled, she said, so she learned to “faint or pretend I was dead, go somewhere else in my mind.” Baez turned to prayer. She was still a little girl and believed God would hear her best from the highest place she could reach, which led her to the tank of the toilet. “How could you let … a man of God — you know, this is someone under you here on Earth — do this to me?” she said. Buried for yearsEventually, Baez did tell her family when she said Peguero tried to target a younger family member. Peguero remained a priest until he died in 2000. The sisters grew up and suppressed their abuse for decades. “As the years go by, you’re trying to bury it all and forget about it and compensate,” Baez said. “Some of us go into drug use, prostitution, suicide. Really, a lot don’t ever make it — they don’t live.” They married and had children of their own, doing what they could to stay busy. But after years of burying it, a flood of emotions came rushing back for both. “All the emotions come back to you and it’s like you can’t breathe,” Flores said. “You’re just frozen and it’s just replaying everything again, and it’s just an awful feeling.” Baez felt it when her daughter was preparing for a rite of passage for Catholic children — First Communion and Reconciliation — when a memory hit her. She remembers a priest holding out his hand to her daughter. That’s when Baez pulled her daughter away. “(I) started crying and gave her to a relative, and I ran into the restroom,” Baez said. “I went hysterical in the restroom. I was curled up on a ball in the floor and everything just started coming back about what that predator did to me when I was small.” ‘Kiss his ring’The sisters and other siblings who said Peguero abused them retained an attorney and sent the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston a letter, prompting a meeting with Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, according to court documents. DiNardo oversees the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston and is now the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. The siblings wanted “him to listen, to hear the truth and say, ‘I’m sorry that happened. I believe you. What can we do to help you? Can you forgive?’” Flores said. As they recounted their abuse to DiNardo, they said the Cardinal never offered the apology they sought and seemed to brush them off. Flores recalled when DiNardo walked in, he “put his hand out, wanted us to kiss his ring, which I refused.” “All he did was say, ‘I’ve never heard of that. (Peguero) was never, never in trouble for anything like that,” Flores said. In a statement, the Archdiocese said DiNardo “has never been comfortable with the ring tradition and he absolutely did not require or suggest that his ring be kissed. Unlike their recollection he recalls apologizing to the family no fewer than three times.” But Baez and Flores remembered the interaction differently. “He did not apologize,” Baez said. “It was a slap in the face to be there, to be asked to come here, and tell your story … and for you to just be looked at and shrugged at.” The sisters and their siblings sued the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston in 2010 for their abuse. Another former member of Our Lady of St. John also filed a separate suit the same year, alleging abuse. The suits all settled out of court. “There is no price that they could ever give to anyone for what they took away from you — your innocence, your childhood,” Flores said. “I mean, they took your soul. How are they going to give it back to you? “You could never replace that. I don’t care how much money they’re going to give to you. … Just say I’m not a liar. It was real. It happened. And he’s the one that did it.” A pleaThe desire to have the Archdiocese admit Peguero was an abuser drives the sisters now. They hope to see his name on the list of “credibly accused” priests that all Texas dioceses plan to release soon. “I want his name to be on there. I want the truth to be known. What was done in darkness, come to light,” Flores said. “That’s all I want.” If his name is on the list, Flores said it would give her “peace and hope.” If not, “he won,” she said. Baez is more optimistic and was certain Peguero will be on the list, but said that won’t lead to forgiveness. They are still reeling from the abuse they suffered as little girls, from a man who was supposed to be a man of God. “I’m angry and torn because people say, ‘Oh, you have to forgive.’ But they’re coming from a religious standpoint,” she said. “(It’s) unforgivable — unspeakable — the things that were done.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.