A ‘new Covenant’ in Ireland

By Madeleine Davies

WHEN the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, welcomed Pope Francis at Dublin Castle last August, he did not flinch from reciting a catalogue of the “dark aspects” of the Roman Catholic Church’s history (News, 31 August 2018). “In place of Christian charity, forgiveness, and compassion, far too often there was judgement, severity, and cruelty: in particular, towards women and children and those on the margins,” he pronounced. “Magdalene Laundries, mother-and-baby homes, industrial schools, illegal adoptions, and clerical child abuse are stains on our State, our society, and also the Catholic Church. Wounds are still open.” Overshadowing the visit, already fraught with fears that the Pope would fail abuse survivors, were fresh revelations from across the Atlantic. A grand jury had concluded that more than 300 priests had abused more than 1000 children in Pennsylvania. It was, Mr Varadkar noted, “a story all too tragically familiar here in Ireland”. His speech was complimentary towards the Pope himself, fulsome in its acknowledgement of the Church’s gifts — the schools that it had established “in the open air next to hedgerows”, the “brave missionary priests and nuns” — and appreciative of the ties between faith and the fight for independence. But nobody watching could be left in any doubt about the balance of power. It was time, he told the Pope, for “a more mature relationship” between Church and State: “a new covenant for the 21st century” — one in which “religion is no longer at the centre of our society, but in which it still has an important place”.

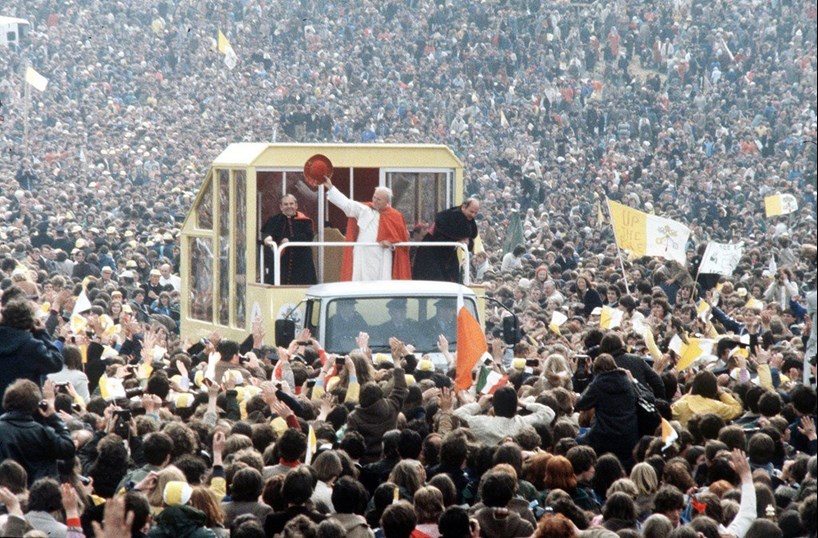

IN THE 30 years since 2.7 million people — almost half of the population — turned out to see Pope John Paul II, Ireland has been transformed. In 1979, it was illegal to sell or import contraceptives, abortion was illegal, and homosexuality was a crime. Today, a gay man leads an Ireland that overturned the abortion ban by popular referendum. Although 78 per cent of people still identify as Catholic, only 35 per cent of them go to mass weekly. This is a high number compared with most of Western Europe, but, in 1979, it was 90 per cent. Just five men were enrolled at the national seminary in 2018 — the same year in which Columba Books, named after a sixth-century Irish saint, published Five Years to Save the Irish Church. “A lot of people ask me: why are you still a Catholic?” the founder of the Irish Hospice Foundation, Mary Redmond, told Dr Gladys Ganiel, when she was researching her latest book, Transforming Post-Catholic Ireland: Religious practice in late modernity. “Imagine! Being asked that question in Ireland!” Dr Ganiel is a research fellow in conflict transformation and social justice at Queen’s University, Belfast. Adorning the cover of her book is a mournful, slowly oxidising angel, its hands joined in prayer in a faded graveyard. “The Catholic Church established a monopoly over the religious beliefs and practices of the majority of people on the island of Ireland,” she writes. “From the vantage point of the early decades of the twenty-first century, there is little doubt that this monopoly has been displaced and Catholicism in Ireland has been transformed.” Yet when I ask her about the chief misconception that people make about her work, she is quick to observe that “the collapse of Catholicism in Ireland can be overdone . . . Culturally, there is still a lot of Catholicism around.” Indeed, in the the opening pages of her book, keen to pre-empt critics, she emphasises that Catholicism has not “gone away”. What she is writing about is “a shift in consciousness, in which the Catholic Church, as an institution, is no longer held in high esteem by most of the population, and can no longer expect to exert a monopoly influence in social and political life”. Such is the freedom with which the Church is criticised — even openly reviled — today that it can be hard to imagine a time when such words were hushed. Two days before Pope Francis was due to arrive in Ireland, a young man posted a question on Twitter: “What’s ur fave story of the church being c***s?” More than 10,000 people “liked” the tweet, and almost 1000 replied, with stories of physical and sexual abuse among those aired. Shame was a prominent theme. One woman recalled how nuns had insisted that the children of divorced couples walk behind the rest of the group at their first communion. “It’s all about power,” one respondent observed. “That power is crumbling now as more and more people find the strength to reject the structures of oppression.” If the Church is no longer “at the centre”, as the Taoiseach put it, has its power really disintegrated? “I think the Church has more of an influence in Ireland than it has in most European countries,” Dr Ganiel says. She points to a recent Pew report that suggested that Ireland was the third most religiously observant country in Western Europe. “What I really found when I was researching the book is that people make this distinction in their mind between the institutional Church, which they think of as the Pope and the Vatican and the bishops, and then the Church on the ground, which is their local priest and the people that go to mass,” she says. “They are very, very critical of that institutional Church . . . [but] most people are very pleased with their local priest and so forth, and have nothing but good to say about them in some ways.”

SHE did not, in fact, set out to write a book about post-Catholic Ireland at all. The original research project that it draws on set out to explore ecumenism and religious diversity. But, in the course of conducting it, she was stuck by the “long shadow that the seemingly steady demise of ‘traditional’ Irish Catholicism cast over the project. . . [I was] surprised by how vigorously some people defined themselves, or their faith community, in contrast or opposition to the Irish Catholic Church.” There is a contrast to be drawn here with the English experience, where to be a “None” often signals ambivalence towards religious institutions rather than hostility. It is hard to predict whether Ireland will follow suit, Dr Ganiel says. “We do know that, when you look at the data for people under 35, they are much happier to say they have no religion than people of older generations. . . It wouldn’t surprise me at all if Catholic identity and mass-going totally collapsed among that generation. At the same time, we do know, as sociologists of religion, that, in countries with a historically Catholic heritage, people tend to hold on to that identification, more so in some ways than in Protestant countries. . . It’s a bit of a stickier identification.” Much will depend, Dr Ganiel suggests, “on what the Church itself actually does in the next five to ten years: whether it is able to establish a place for itself in Irish society that is kind of relevant to people, and especially relevant to that younger generation.” Among those interviewed in Transforming Post-Catholic Ireland is Ben, a 25-year-old postgraduate student involved with a collaborative lay-clerical Jesuits’ young adult ministry. Among his observations was the importance of social action: “I think, to be honest, if there wasn’t an element of ‘social justice’, I don’t know how relevant [church-going] would be for me.” The young people involved in this ministry “perceived themselves as truly living out their faith in ‘another way’ than that of stereotypical, traditional, passive Irish Catholicism,” Dr Ganiel observes. One recalled: “My experience of church would have been, you just go to mass on Sunday, and that’s it. And, when you’re home, your ma asks you who said mass to make sure you were there.” Another, Patricia, a 62-year-old member of a PCC in Dublin, spoke of ignoring the institutional Church “as best I can”. The younger generation, despite low levels of mass attendance, were “an awful lot more Christian” than their forebears, she suggested. “They really care about each other.” “I don’t have any fears about their spiritual health,” she observes. “I find mass on Sunday nourishing — and I wouldn’t be able to cope without that nourishment — but I’m sure they’ll find whatever is good for them.”

TO A significant extent, the story of the declining power of the Roman Catholic Church entails the faltering of a powerful alliance between mothers and priests. Women were once, Dr Ganiel notes, one of the key drivers of Ireland’s “abnormally high rate of vocations”. Their entry into the workplace, in the 1980s and ’90s, and the Church’s stance on contraception, were key drivers of change. Three-quarters of the Irish Catholic women who responded to a 2010 Trinity College Dublin study stated that the Church did not treat them with “a lot of respect”. “May I remind your readers how far Irish women have come,” Aida Lennon Kilmacud, of Dublin, wrote to The Times recently. “Back then, we had to wear headscarves to mass, were not ‘allowed’ inside the altar rails except to wash the floor, and could not attend our own baby’s baptism as we had not yet been ‘churched’ [cleansed], with the christening fast-tracked to save the baby from limbo.” “Vincit qui patitur,” she signed off (“They conquer who suffer and endure”). One of the most vocal critics of the Church is a former President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, who described it as “an empire of misogyny”, and the World Meeting of Families as “a right-wing rally”. During the month of the Pope’s visit, RTE broadcast the programme Mary McAleese’s Modern Family, which included a visit to two men who had fostered a five-year-old boy in rural Ireland. An opinion poll carried out by the Irish Independent found that more than half of respondents agreed that the Church did not treat women equally. Two-thirds stated that it should ordain women and allow priests to marry. But it was the abuse scandal, and speculation about whether the Pope would apologise, that dominated the media narrative in those weeks, Dr Ganiel recalls. “The impression that Irish people are very critical of the Church stems a lot from the abuse crisis, and the abject failure of it to be handled in a satisfactory way internationally or in Ireland.” In the weeks after the visit, she conducted polling that revealed that only 30 per cent of respondents thought that the Pope had done enough to address abuse during his visit, rising to 50 per cent of practising Catholics. Of the 80 per cent who did not attend any of the events during the visit, 51 per cent cited “I was not interested”, while 30 per cent said that they disagreed with the Church’s handling of child sex abuse. Fewer than 130,000 people attended the papal mass in Phoenix Park, for which 500,000 tickets were issued. People are not confident that the Church is now on the right path, she says. The resignation in 2017 of Marie Collins, a survivor of clerical abuse, from the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, was a “damning indictment”. In her letter, Ms Collins cited the reluctance of some members of the Curia to implement the Commission’s recommendations, despite their approval by the Pope, as the biggest problem: “It is devastating, in 2017, to see that these men still can put other concerns before the safety of children and vulnerable adults.” Dr Ganiel believes that Pope Francis’s apology, delivered during the penitential rite at mass in Phoenix Park (News, 24 August 2018), was “probably one of the better apologies that someone speaking on behalf of the Church has given in Ireland”. But words are not enough, she says. “They are still kind of waiting for action to come, and I think they expect Francis to lead that — and there is a sense of disappointment that he hasn’t really done that.” Writing in The Tablet on the eve of the visit, she noted that the State had picked up all but ?115 million of an estimated compensation bill of ?1.1 billion for survivors. “The Church, it seems, pays a mere pittance for its crimes.” THE article “Only the people can now save the Church in Ireland” reflected a strong theme in Transforming Post-Catholic Ireland: a shift among the laity from passivity to extra-institutional action.“It is only when people take responsibility for their own religion that revival follows,” she suggests. Some, like Roy Foster, have suggested that Catholics in Ireland are becoming “Protestant”, she notes. “That kind of stereotypical Protestant attitude: that it’s not so much conformity to the institution that matters, but your individual conscience.” The people she interviewed were “passionate about this idea that faith could make a difference in Irish society, and they weren’t really that pressed whether that happened through the institutional Church or not,” she recalls. “They thought the Christian message was compelling, and it could contribute to the common good, with or without the institutional Church.” The concept “extra-institutional” is important, she argues, in providing a counter-balance to the idea that contemporary religion entails constructing “a God of one’s own, quite unmoored from traditional religious institutions”. It is “more solid”, because those involved still maintain some sort of relationship with institutions. These practices have more potential to contribute to reconciliation in Ireland than traditional denominations, she argues: they have “more freedom and flexibility to critique and speak to the mainstream”. Case studies tell the story of an increasingly diverse “religious market”, from a multi-ethnic Pentecostal congregation in Limerick, many of whom had Catholic backgrounds, to an ecumenical one under Methodist oversight with more than 20 nationalities represented, including many Africans. Pentecostal and Charismatic churches are “now noticeable actors”, she notes — the second fastest-growing denomination, after the Orthodox. Members of one such church, Abundant Life, described being helped by the “maturity” of immigrant members: “They really believe in putting God first in every aspect of their lives.” Among Dr Ganiel’s interviewees were immigrants who were “shocked” at what they found in the Catholic Church in Ireland. Enoch, an African, was surprised that mass lasted only half an hour rather than two, and that, while his church at home was full, most of those in the pews in Ireland were “of the older generation”. Magdalena, an Eastern European, says that her ideas about faith in Ireland were “crushed”. “I was Googling to try and find out a little before I came here, and every congregation had a website. . . So I thought, this is so vibrant. And it was so the opposite.” Another case study is Holy Cross, which, in 2004, became the first Benedictine monastery to be opened in Ireland in 800 years. Devoted to “spiritual ecumenism” and reconciliation, the monks are openly critical of the Church, including its response to the abuse crisis, and the monastery has become a “a place of refuge for Irish Catholics who had been hurt and disappointed by their Church”, but also people from other Churches. The message is that “the people are the Church.” WITH vocations to the priesthood so few, a shift away from a clerical model may become inevitable. “Ireland faces a priestless future, for which no preparations are being made,” Fr Bernard Cotter, a parish priest in the diocese of Cork and Ross, wrote in The Tablet in August. “Instead of planning for the obvious future, prayers for vocations are insisted on, even though the clerical model that led to such abuse of power and of vulnerable people is visibly coming to its end.” Those who do enter face a public steeped in stories of abuse and hypocrisy. Priests interviewed by the Royal College of Surgeons spoke of feeling “besieged” in places where they were not known, Dr Ganiel says. “One priest put it, ‘I feel I am wearing a paedophile uniform.’” Yet, while there is no shortage of negative or satirical depictions of the priesthood in modern culture, there are positive pictures, too. The 2014 film Calvary, for example, tells the story of a priest who remains at the heart of a hurting community. “The unknown priests in the hierarchy are sort of stereotyped as bad, whereas the known priest, and the local, if you have had good interactions with them, are seen as a good guy doing a hard job,” Dr Ganiel says. Her next book is a biography of Fr Gerry Reynolds, a hero of the peace process. “In the early years of the Irish state, the Catholic Church did provide a lot of the man- and woman-power that educated the country, provided health care, and social welfare,” she observes. “It attracted some of the brightest and best of the Irish young people to serve society. People are critical of the Church, but I suppose they are aware of, and remember, that legacy, particularly from the ’60s and ’70s. There is a significant tradition in the Irish Church of social justice and calling out the State when it sees policies as unjust or unfair to the poor.” The Catholicism being displaced, she writes in the book, was “a defining characteristic of Irish nationalism, that had a ‘monopoly’ on the Irish religious market, that had a strong relationship with state power, that elevated the status of the cleric to extraordinarily high levels, and that emphasised the evils of sexual sin. At the same time, for many it was a Catholicism that provided comfort and fuelled their spiritual and ethical imaginations.” Among the texts that commentators drew on during the Pope’s visit was Seamus Heaney’s “A Found Poem”: . . . There was never a scene when I had it out with myself or with another. The loss of faith occurred offstage. Yet I cannot disrespect words like “thanksgiving” or “host” or even ‘communion wafer’. They have an undying pallor and draw, like well water far down. The author of the prize-winning novel A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, Eimear McBride, has said: “You know, being Irish, oh, God, sex, death, religion, shame, here it all is. I thought, I really don’t want to write this book, but, you know, it’s a bit like asking English male writers not to write about the war. It’s just there, and it’s going to come out at some point.” Conducting her research, Dr Ganiel found that “people on the island could not stop talking about Catholicism — whether they were Catholic or not, whether they were Irish-born or not.” Among those she interviewed was John, a 33-year-old Catholic father (and visitor to Holy Cross) who had hope for the future of the Catholic Church, and was passionate about the laity’s responsibility. “As a Catholic, I believe in the communion of the saints and intercession of prayer throughout the ages; so I have to be hopeful,” he told her. “I’m looking at it in the context of the Irish Church over the last . . . 1500 years, and the depth and experience of the people that there are possibly in heaven, who are all rooting for us young Catholics down here now, and the journey that we’re on.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.