|

For some Pennsylvania laity, being Catholic has become embarrassing and troubling

Religion News Service

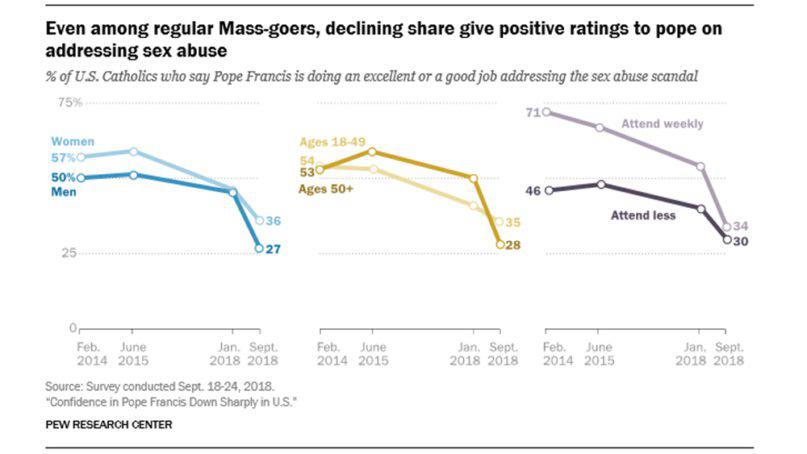

For 20 years, Kathleen Trazzera served Catholic parishes in suburban Philadelphia as a Eucharistic minister and a lector. This past September, she and her husband gave up. The Pennsylvania grand jury report released last summer was the last straw, said the 63-year-old registered nurse. “It got to the point where I just couldn’t defend participating anymore,” said Trazzera, who said her husband made that decision first. “We’re just not comfortable with supporting the Catholic Church.” The grand jury investigation, which looked into six Pennsylvania Catholic dioceses, found that approximately 300 clergy had been “credibly accused” of participating in the abuse of more than 1,000 child victims over seven decades. The grand jury’s report has left some lay Catholics wondering whether church leaders can be trusted to safeguard their children or even to tell the truth. “I am outraged, I am embarrassed, I am mad. It has nothing to do with faith, and everything to do with the people running the church,” said 45-year-old Michael Garasic, who grew up in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, one of the dioceses in the report. Garasic, who has spent most of his career in public safety and now lives in Bradenton, Fla., has two children, ages 8 and 4. The tipping point for him, he said, was reading the report and seeing what the clergy had done to children. “That made me question every dollar I or my parents had given, everything I’d ever done for the church,” he said. As he sat in church with his wife and daughters, Garasic said, he’d look at the priest dispensing moral instruction at the front of the sanctuary and shake his head. “How can you talk to me and tell me how to act when your peers are doing heinous crimes and your peers are covering it up?” he said. Garasic, who still attends church with his family, has written to his congressman, Rep. Vern Buchanan, suggesting that sexual abuse on church property be considered a federal crime. Garasic has also written several cardinals. He said that only Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston ever responded. Kathy Kane, who co-founded the child-safety advocacy organization Catholics4Change in 2011 after a grand jury investigation into the Philadelphia Archdiocese, said the 2018 Pennsylvania report was impossible for many Catholics to overlook. She also pointed to allegations of abuse against Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington, D.C. “The coincidence of the grand jury report and the McCarrick (allegations) made the perfect storm,” said the 51-year-old Kane, a social worker in the Philadelphia suburbs. Kane said she is “estranged” from the church’s leaders but says she is “still Catholic 24/7.” But she finds it uncomfortable to sit in church, given the reports of abuse. According to 2014 Pew Research Center data, Catholicism has experienced the greatest losses due to what the report calls “religious switching.” “Among U.S. adults, there are now more than six former Catholics (i.e., people who say they were raised Catholic but no longer identify as such) for every convert to Catholicism,” said the researchers. Almost 13 percent of Americans identify as “former Catholics,” according to Pew. Phil Heron, editor of the Delaware County Daily Times in Swarthmore, Pa., is one of them. He has written about clergy sex abuse, saying he too is estranged from the church. Swarthmore is part of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which has been the subject of two grand jury investigations and has set up a reparations fund for victims of abuse. “I now question whether I need a priest — or the church — to have a relationship with God. I miss the sacraments. But not a lot else,” he wrote last August. Heron turned down a request to be interviewed “The truth is I’m something of a lapsed Catholic at this point. I’m not quite sure what to make of my faith,” he wrote in an email. Younger Catholics may not be aware that prior sex abuse scandals happened at all, said Julie Byrne, a professor of religion at Hofstra University and author of “The Other Catholics: Remaking America’s Largest Religion.” “What’s different now is that it’s reaching a different audience. It’s happened again for a different generation,” said Byrne. In the case of older Catholics, even what Byrne called the more traditional “John Paul II and Benedict” variety, these new revelations may have “rocked their faith.” “It made them think about it and we don’t know the effect yet,” she said. Byrne and her siblings grew up near Lebanon, Pa., and had met four of the clergy on the list of alleged abusers, she said. Her family also knew some of the alleged victims. Though neither she nor her siblings attend Mass regularly, “we all retain some skeins of Catholic identity,” she said. But Byrne also sees the sex abuse crisis as a symptom of larger problems within the church, and within society, given that sexual abuse is more likely to happen in a family setting. “Everyone wishes the Catholic Church would be better than it is, and unfortunately, it’s not,” she said. “People would like the problem to be localized. If it’s about one institution, you can fix it. … Human nature is harder to fix.” In the months since the Pennsylvania grand jury report was made public, approximately 50 American dioceses and religious orders have made names of priests who molested children public. Another 55 have said they will soon do so, according to an analysis by The Associated Press. This month, Pope Francis is convening a global conference of bishops to address the international crisis. But, according to Pew, U.S. Catholics are increasingly less sure the pope can effectively tackle the problem. A religious studies professor at Villanova University, Massimo Faggioli, has written several books on the role of the laity in the Catholic tradition. In the United States, unlike places such as Germany and Australia, where there are organizations that represent lay interests, those who are not ordained don’t have an official voice, he said. “There is no unified body that can represent the voice of the Catholic lay people,” he said. The crisis has revealed a structural problem in the American Catholic Church, he said. Though sexual abuse in the church has been discussed since the scandal broke in 2002, the revelations of 2018 may be a potential turning point, he believes. Change may come to the church. But it may be too late for some. “Very few Catholics believe what the bishop says. People are leaving because they don’t see change happening or happening in a short time. Catholics are leaving precisely when it is time to explore the possibility of change,” he said. But things won’t change, said Garasic, until every misdeed is exposed. “To be a Catholic is not only embarrassing but troubling,” said Garasic. “Where will it end?”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.