|

Texas pastor who leads Baptist search didn’t stop alleged abuse at Dallas-area church

By Lise Olsen

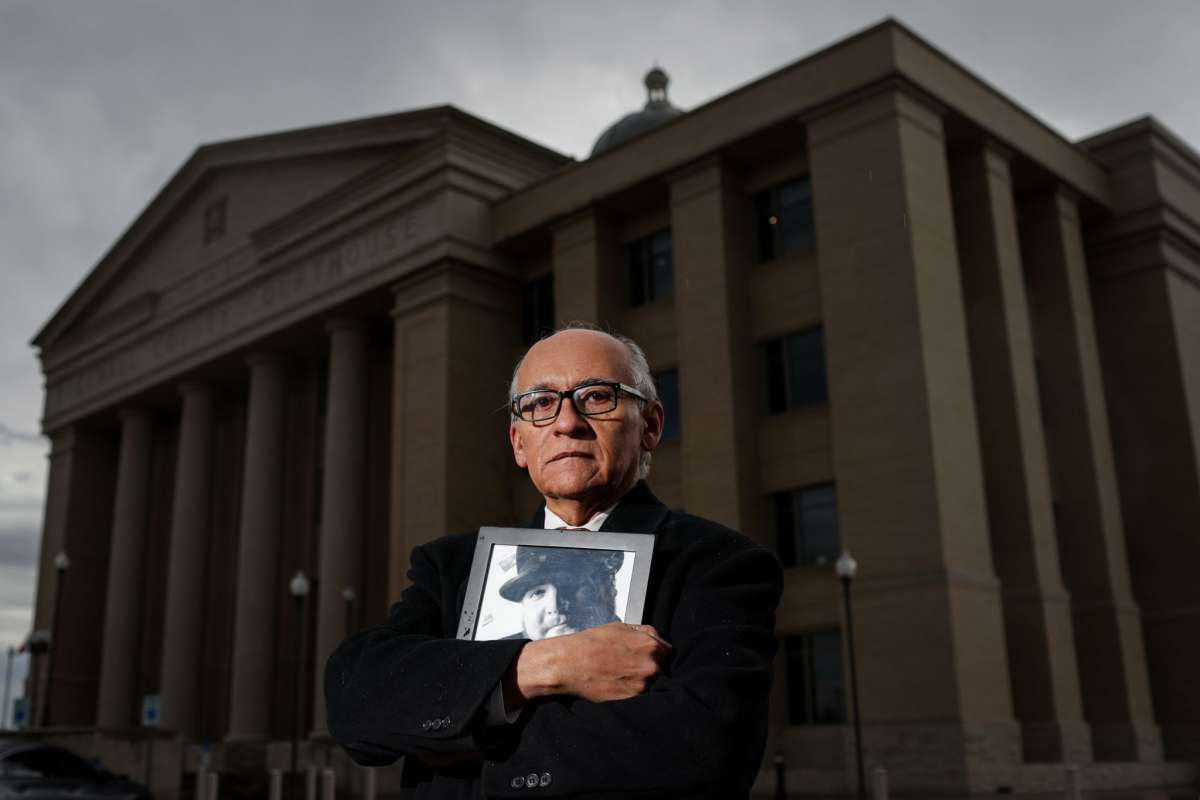

For the past few months, pastor Steve Swofford of First Baptist Church in Rockwall has led a national search committee tasked with finding a leader to guide the Southern Baptist Convention through a national sex abuse crisis. That six-member committee is expected to name a new president of the SBC Executive Committee on April 2 — weeks after the Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News published an investigation into sexual abuse in Southern Baptist churches. In response to the series, "Abuse of Faith," other SBC leaders already have promised to probe churches whose leaders knowingly harbored child abusers. But Swofford has never spoken publicly about a scandal closer to home: allegations that a former youth pastor and the youth pastor's assistant each molested prepubescent boys from his own church in the 1990s, according to interviews and information the Chronicle obtained from civil lawsuits and Harris County criminal records. Swofford has been pastor of the church east of Dallas since 1989, according to the church's web site. Though allegations made by one former youth group member received publicity after his family filed suit in 2015, most of what was alleged about the two men's sexual abuse of minors in Swofford's church in the late 1980s and early 1990s has not before been reported. Youth pastor Billy Bob Burge, who worked at First Baptist Church of Rockwall for about a decade, stood out as a colorful figure — he wore loud Hawaiian shirts, had a shock of canary yellow hair, used hip lingo and offered trips to local water parks and gifts to boys he particularly liked. A younger man, Jason Leon Austin, served as his sidekick. Austin was an odd choice for that role; Harris County court records show that he was a convicted felon on parole for the 1989 molestation of a Houston boy at the time he worked with Burge as his assistant. Three Rockwall suburban Baptist moms whose boys went to the church youth group say they didn't know Austin had a criminal conviction prior to the time he worked with their sons. For years, they figured their children benefited from all that pastorly attention. In the 1990s, Austin and Burge often rode around together in white vans with the church's logo on the side, sometimes driving down Serenity Lane to pick up Jeremy Sweet-Gomez from the house he shared with his mother, her second husband and his two sisters. Years later, in October 2014, Gomez began telling family and close friends that Burge had sodomized and sexually abused him and at least two other pre-teen boys during some of those church-sponsored trips, according to records and interviews. His family later filed a civil suit, accusing the church of a cover-up. Another lawsuit described how Austin twice attacked another Rockwall boy, performing "attempted forced oral sex, attempted forced sodomy, groping, fondling, and forceful removal of (victim) Jonathan H's clothing" inside First Baptist Church of Rockwall property. Both cases were dismissed in July 2017 because the statute of limitations had lapsed for complaints related to the alleged assaults in the 1990s. But many unsettling questions raised by victims and family members remain unanswered. Swofford and other church officials did not explain in response to the civil lawsuits why Burge abruptly left their church — or why Austin was allowed to work with youth there despite his felony conviction. It's unclear whether Swofford was told before 2015 about allegations that Burge molested three or more members of the youth group, but Austin's abuses were reported quickly to a choir member and to Swofford a few years after the alleged attacks in Houston and in Rockwall, records show. The unresolved issues from the civil lawsuits have led to questions about Swofford's role in the search for a new Baptist leader. Ed Gomez, a criminal defense lawyer and the father of abuse victim Jeremy Sweet Gomez, said Swofford set a poor example of how to handle abuse allegations inside a church. "When I discovered that fact that Pastor Swofford is part of that committee...it literally took my breath away," Gomez said. "How can he be part of a committee to institute reforms when he didn't do it in his own church? "His own church should be investigated over what happened for these boys being abused by Billy Bob Burge and Jason Leon Austin because these are not isolated incidents." Gomez never got the response he had waited for, his daughter said. Her father died March 3, about a week after speaking with the Chronicle. Swofford is a past president of the Southern Baptist Convention of Texas and a former executive committee member of the Southern Baptist Convention. He didn't reply to the Chronicle's requests for an interview about his experience dealing with the Gomez family and the mother of Jonathan H., who made complaints about child abuse at his church. Oklahoma-based Baptist pastor Wade Burleson, who has pushed the SBC to reform its practices on sexual abuse, worked with Swofford when both were trustees on the convention's International Mission Board. He calls Swofford an "old guard" pastor, among those who "have a desire to always keep problems a secret." To clean things up, the SBC should be looking for a different type of leadership that is willing to be more open, he said. Dallas-based activist Amy Smith, who has worked for years as a blogger to expose allegations of sex abuse inside Southern Baptist churches, said she considers Swofford part of the group of Baptists that want to cover up rather than clean up. "This is evidence that the SBC from the top down is all words and no action in their response to widespread sexual abuse in their ranks," she said. "The good ol' Baptist boys club strikes again. The trail of damage done by sexual abusers and their enablers in the SBC is ongoing and devastating." Other members of the SBC search committee and its executive board did not respond to requests for interviews or declined to comment. The new president of the executive committee will replace Frank Page of South Carolina, who resigned last year for a "morally inappropriate relationship in the recent past." There is no indication that the relationship involved illegal behavior. An early death Jeremy Sweet Gomez was 37 when he first began to tell close friends and family about being abused by Burge. Gomez, the name he preferred, had been a scrawny kid of 11 or 12 when he and a pack of neighborhood kids joined the church youth group in the 1990s. But by December 2014, he had grown into a bouncer and process server, a burly denizen of the tattoo parlors and live music venues of Dallas' Deep Ellum historic district. He was known for wearing his signature checked Vans tennis shoes. Late one night, Gomez told his sister he had started to have flashbacks. Gomez said he kept remembering a day when he had been changing out of wet swimming trunks after a church-sponsored outing to a Garland water park when Burge barged in. "All of a sudden... there was a finger in my butt. I didn't know what to do or how to feel and I didn't know what was happening," Brittany Gomez remembers her brother saying, according to her interview with the Chronicle and a deposition her mother gave that describes the incident. Gomez recalled other attacks too, but knew, as the son of a criminal defense attorney, that it was too late to pursue criminal charges for what his family's lawsuit later described as "sodomy, oral sex, and inappropriate sexual touching... (that) occurred at various locations and times: including on church property and during church-sponsored religious trips." Then on December 7, 2014, Gomez got together with three friends from high school. He was standing on a friend's porch, his bearded face illuminated by a strand of colored Christmas lights, when Burge's name came up. A younger friend, who had also been one of the smaller boys aboard Burge's church bus, unleashed an expletive and announced he too had been abused. He added that another friend had confided being groped and fondled. That meant there were at least three victims in their small circle of friends, according to allegations in the civil suit and interviews with three out of four people at the gathering. "Then I realized...it wasn't just me," Gomez later told his mother by phone. The revelations seemed to bring Gomez more grief than comfort. Despite years of counseling and struggles with depression, alcohol and drug abuse, Gomez, the eldest of three siblings, acted as the family joker. That December, he told his little sister he knew he needed to lose weight because he'd tried to hang himself and the pipe wouldn't hold. She didn't laugh. Then on Jan 19, 2015, he called again. He sounded groggy and left a jumbled voicemail that ended with: "I'm sorry for what I'm going to do." By the time his parents reached his Deep Ellum apartment, Gomez was dying from an overdose. Months later his grieving family united behind the idea of using a civil lawsuit to keep his story alive — and to expose Burge, who by that time had left Rockwall but still worked as a minister at another church nearby. Church leaders betrayed the family's "trust through their actions and omissions which left (Gomez) unprotected from a sexual predator and resulted in him enduring numerous incidents of sexual abuse. These abuses ultimately led to his injuries and death," the lawsuit said. Lawsuits dismissed The family's legal efforts had mixed results. The reaction was immediate at Burge's new church in Greenville, Texas, where leaders obtained Burge's resignation soon after the suit was filed in September 2015. The pastor made a public statement to members, encouraging them to come forward if they had experienced problems with Burge. A few months later, Jonathan H. — who had moved out of state — contacted the family and shared his own story about being abused by Austin, Burge's assistant. Jonathan H. added his voice to the Gomez' family, filing his own lawsuit. Both accused church officials of protecting pedophiles and of failing to warn parents and children of the dangers. But officials at First Baptist Church of Rockwall denied all allegations against their ex-workers and pushed to dismiss the cases because the statute of limitations had expired. In June 2017, a judge agreed, dismissing the lawsuits. Burge did not respond to a request for comment sent to his attorney and to a family member. He recently offered prayers at a city council meeting in Goliad, Texas, southeast of San Antonio, minutes show, but does not appear to work at a church. Austin declined to comment on allegations made against him in Rockwall. He was locked up again in 1994 for violating his parole — a few years after he allegedly abused Jonathan H. — and remains a registered sex offender in Texas, state police and prison records show. Two attacks Jonathan H. said he was about 10 years old when Austin, who began working in Rockwall and Houston churches as a teenager, first began following and bullying him, according to interviews and civil courts documents. One afternoon, he was playing tag with another kid when Austin chased him "through the hallway" at Rockwall First Baptist Church. Austin followed when Jonathan hid and then tried to go to the bathroom. "He grabbed my throat in a reverse choke hold — pulled me back and then started trying to rip down my pants. ....He was choking me — I couldn't breathe. I started kicking him and elbowing him and he let me go," Jonathan told the Chronicle in 2019 in the first interview he has given. Another day, Jonathan was waiting for his mother, who worked at a church-sponsored school, when Austin cornered him in an empty classroom. "He got me from behind, trying to roll me over to (assault me) ... I started screaming my head off — my pants were down at that point." Both incidents occurred inside the church in about 1989 or so, the lawsuit alleged. Swofford became pastor in 1989. At that time, Austin worked in the nursery as a part-time paid worker, according to a deposition provided by Jonathan's mother, who also worked for the church from 1987-1990. In its answer to the lawsuit, however, the church said he was never a paid employee. Austin grew up in Rockwall County, but left there in the summer of 1989, enrolled in Houston Baptist University and became a "youth pastor" at a Baptist church in Houston, Harris County criminal court records show. On October 7, 1989, Austin spent the night in the home of a church family, crawled into the bed of an 11-year-old boy at 5 a.m., disrobed, rubbed his sex organ against the child and ejaculated. In the morning, that boy told his parents, who called police, records show. Austin confessed to the child's father and said that "he had that problem before." In November 1990, Austin was convicted of indecency with a child in Harris County. He went to prison with a 10-year sentence, but won release two months later as a first offender and returned to Rockwall. After his arrest and as a convicted felon, Austin served as an assistant under Burge in the First Baptist Church youth program in the early 1990s, according to Jonathan H.'s civil lawsuit and court records. From 1991-1994, Austin, described in civil lawsuits as the church's assistant youth pastor, was on parole and ordered to avoid unsupervised contact with children, according to criminal records and allegations in the civil lawsuit. Jonathan H. had moved away from Rockwall himself in about 1990. But he returned as a teenager and began suffering panic attacks. He told a counselor and his mother about Austin's assaults in 1997 after he attempted suicide, according to interviews and a deposition his mother provided in 2017 as part of the civil lawsuit. His mother, a former church employee, contacted Swofford. He told her about Austin's Houston conviction but had not alerted parents in the Rockwall church, the family's civil lawsuit alleges. In a meeting in about 1997, Swofford told her that she "didn't know that (the attacks her son described) had happened at his church" and that the statute of limitations "had run out" to file criminal charges against Austin in Rockwall, the mother said in her 2017 deposition. In a letter to the family, Swofford offered support for Jonathan to be recognized as a crime victim despite the family's decision not to seek prosecution. "I rejoice with you guys that Jonathan, through much counseling and help, has not only been able to identify what has been troubling him, but has begun to successfully deal with it," Swofford's letter said. "...Knowing that the one who did this to Jonathan has already been punished in another similar matter allows us to find some comfort in the fact that he has not gone unpunished. In light of that, and because of his emotional instability, for others to make Jonathan relive the pain and go through the process again would serve no purpose." Contact: lise.olsen@chron.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.