|

St. Joseph's Training School abuse: Why papal apology matters to survivor, 60 years later

By Bruce Deachman

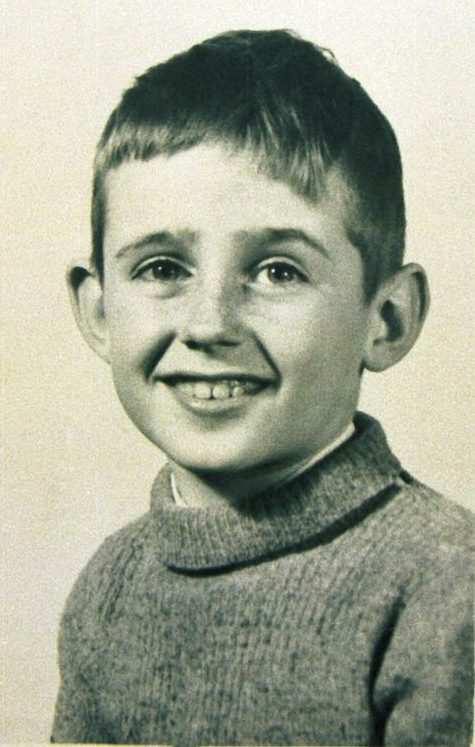

The dimly lit conference room looked like so many others — a long table with nameplates and microphones, surrounded by drab olive drapes and beige carpet. On this particular Thursday, however, two things stood out: a painting of the Virgin Mary and Baby Jesus on the wall behind the head table, and the speaker whose back they appeared to be looking at: Pope Francis. Wearing his white cassock, the Pope faced the tiered rows of cardinals, archbishops, bishops and other clergy in their respective plumage, and in under two minutes read his opening address, delivering his words in a dry monotone and barely lifting his eyes to look at his audience. The occasion was the Meeting on the Protection of Minors in the Church, a four-day summit held at the Vatican in February for Roman Catholic officials to address the issue of the abuse of minors by church clergy. “In the face of the scourge of sexual abuse by churchmen to the detriment of minors,” the Pope said, “I have decided to meet you, patriarchs, cardinals, archbishops, bishops, religious superiors and leaders, so that together we might listen to the Holy Spirit and, with docility, with its guidance, hear the cry of the little ones who plead for justice.” He demanded that action be taken: “The holy people of God look to us and expect from us not simple and predictable condemnations, but concrete and effective measures to be put into place. “We need to be concrete.” In the end, however, concrete measures were not taken. Delivering a Sunday mass to mark the end of the conference, the Pope laid much of the blame for the abuse on the devil’s doorstep: “The consecrated person, chosen by God to guide souls to salvation, lets himself be subjugated by his own frailty, or by his own illness, thus becoming a tool of Satan,” he said. He also challenged the world at large to solve the issue. “There aren’t enough explanations about child abuse,” he said. “Humbly and bravely we must recognize that we stand before the mystery of evil, which rages against the weakest because they are an image of Jesus. This is why in the church there is now a growing awareness of having not only to try and stem the most serious abuses with disciplinary measures and civil and canonic trials, but also to face the phenomenon decisively both inside and outside the church. “It feels it is called to fight this evil that touches the centre of its mission to announce the Gospel to the little ones and to protect them from the ravenous wolves.” The National Catholic Reporter, an American newspaper that reports on matters involving the Roman Catholic Church, described the Pontiff’s concluding remarks as “a melodramatic avoidance of the truth.” David McCann wasn’t particularly surprised by the church’s response. For decades, he’s been trying to get an official apology for the abuse that he and hundreds of other boys suffered at a Catholic training school in Alfred, about 70 kilometres east of Ottawa. “It’s still the same ‘I-hope-that-you-eventually-get-what-you-want’ sentiment, but no commitment on their part to apologize,” McCann said recently from his home in Vancouver. “You can have all the pretty words you want, all the promises, all the commissions, and bring people in from around the world, but if you can’t spend 10 minutes saying ‘I’m sorry,’ I don’t think you’re that serious. I don’t think they know how to deal with it. It’s a bunch of old men in dresses who don’t have a clue.” It has been six decades since McCann was abused, and 30 years since he went public with his story. His decision to do so opened a floodgate of similar allegations from more than 1,600 former wards of either St. Joseph’s Training School for Boys, in Alfred, or St. John’s in Uxbridge, about 70 kilometres northeast of Toronto. More than 120 perpetrators were identified by former students, but by the time McCann came forward, many of the accused had died, while others were deemed too infirm to stand trial. Still, almost 200 charges were laid against nearly 30 De La Salle Brothers of the Christian Schools and Christian Brothers of Ontario, the Catholic religious lay orders that ran the schools, and other staff. At the time, it was the largest such scandal to come out of Canada, although similar stories have since surfaced all over the world, most notably, perhaps, the hundreds of cases of abuse in Massachusetts uncovered by the Boston Globe in 2002 and depicted in the 2015 film Spotlight. The Globe’s investigation led to even more cases coming to light. Only last month, former Australian Archbishop and Cardinal George Pell was sentenced to six years in jail for molesting two choir boys in the 1990s. Pell is the highest-ranking Catholic official to be convicted of child sexual abuse. In a 2014 interview with La Repubblica newspaper in Italy, meanwhile, Pope Francis said that about two per cent of Catholic clergy members — or roughly 8,000 — including priests, bishops and cardinals, were pedophiles. The Pope referred to them as a “leprosy” within the Church. Among the 16 convicted of abuse at St. Joseph’s and St. John’s was McCann’s chief tormentor, Brother Joseph, a.k.a. Lucien Dagenais, who was given a five-year sentence after being found guilty of seven counts of indecent assault, six counts of assault causing bodily harm and two counts of buggery. Throughout the court proceedings, Dagenais showed no remorse and maintained his innocence. In passing sentence, Justice Hector Soubliere noted: “We built walls around that school: not of brick and mortar, but of much stronger material — walls of silence and indifference. I’m even tempted to say walls of ignorance.” And while the memory of the crimes committed by Dagenais and others has, in many cases, been blurred by the passage of time, their rough edges worn smooth, the physical and psychological damage inflicted on the boys placed in their care often remains. Now 72, McCann says he’s never really healed. “I still pay the price,” he says, noting that he lives alone and hasn’t been in a serious relationship in years. He well recalls lying frightened in the dark, one of about 50 youngsters in a room of steel-framed beds laid end-to-end, row upon row, and hearing footsteps approach. It was December 1958, and McCann, then a 12-year-old delinquent from Kingston, had, along with two friends, been arrested the previous month after the trio went on a one-night crime spree, breaking into and robbing eight Kingston businesses of, among other things, $300 in cash, a $50 watch and some sticks of dynamite. His accomplices got probation, but McCann, already no stranger to the courts, was sent to St. Joseph’s. “I believe that at St. Joseph’s Training School there will be discipline and the instruction given to him that will try and correct his ways,” said Judge James Garvin. “We hope so anyway.” A psychologist, Dr. Oscar Karabenow, thought otherwise, but his report to McCann’s probation officer arrived too late: McCann had already been taken from school by a police officer and driven to St. Joseph’s. A scrawny, freckle-faced boy with big ears, McCann wasn’t tough. True, he frequently skipped school, but often to go read at the Kingston Public Library. He had never been away from home before. At St. Joseph’s, a provincially funded reformatory, he found an imposing and menacing institution — a stone building he recalls today as cold, smelly and dank. The charges there were overseen by men in black robes, members of the De La Salle Brothers of the Christian Schools, an order with roots in early-1700s France. The Brothers had petitioned the Ontario government to create a school for delinquent Catholic boys — St. John’s Industrial School, which opened in 1895. St. Joseph’s opened in 1933, with three dozen boys shipped there from St. John’s. At the school’s opening ceremony, Ontario premier George Henry remarked that “No child should emerge from industrial schools without a better outlook on life.” Speaking on behalf of the Christian Brothers, Brother Martial, the superior, pointed to the inscription on the lintel stone above the main entrance, which read, in French and English, “Young man, I say, Arise.” “The command is divine,” he noted. “We are but the humble instruments, but if in the passage of years, we can but point to one man whom we were permitted to help on to the right road, then would this investment of labour and of love not be in vain.” William Martin, the province’s minister of public welfare added: “The passion, zest and enthusiasm of youth must be safeguarded and guided into the proper channels if the future of civilization is to be made safe and secure.” While many of the boys in their charge had been sent to St. Joseph’s for criminal misdemeanors, not all had run afoul of the law. Upwards of 30 per cent of the boys were runaways from residential schools, while others were “unmanageables” who simply proved too much for the parents or guardians who sent them there. At any one time, there were about 160 boys at the school, some sent there from as far away as Kenora. The purpose of the schools, as outlined in the Training Schools Act of 1937, was “to provide the boys or girls admitted therein with a mental, moral and vocational education and training and with profitable employment.” But former Renfrew North Liberal MPP Sean Conway recalled in 1996 in the Ontario legislature the school’s reputation as “synonymous with some kind of Alcatraz” when he was a youngster. “On more days than I can remember,” he said, “in the elementary school, the very Catholic elementary school to which I was sent … we were told, ‘Be bad and you’ll go to Alfred.’” On this particular night, McCann listened and the footsteps stopped at his bed, and a tall figure leaned over and whispered in the young boy’s ear, “Viens avec moi.” McCann didn’t understand French, so Brother Joseph mumbled the phrase again, this time in English. “Come with me.” Known to the boys as The Hook for a table saw accident he’d suffered years earlier, leaving him with just his middle finger and stump of his thumb on his left hand, Brother Joseph took McCann to a room off the dormitory, and raped him. “I don’t remember all the details,” McCann admits. “It’s something I don’t try to think about very often. But it was repeated several times.” It was repeated not just with McCann, but hundreds and hundreds of boys, both at St. Joseph’s and St. John’s. The abuse came in all forms: sexual, physical and psychological. “I saw grown men — beefy guys — beat little frail 11- and 12-year-old kids into a pulp and unconsciousness,” recalls McCann. “They beat them black and blue.” “They ripped the kid out of me,” said former St. Joseph’s ward Gary Sullivan in 1990, according to journalist Darcy Henton’s 1995 book, Boys Don’t Cry. “It was nothing but absolute terror.” In the Recorder’s Report Concerning Physical and Sexual Abuse At St. Joseph’s and St. John’s Training Schools for Boys, prepared by Benjamin C. Hoffman and presented to the Reconciliation Process Implementation Committee in 1995, a number of former students spoke anonymously of their experiences at the schools. “I have hated, hated all my life,” said one who was sent to St. Joseph’s in 1938, five years after it opened, when he was nine. “I cannot express love, I have never known love. My son loves me and I don’t show him love.” “I saw many young children beaten up and strapped,” recalled another. “I saw Brother —— wake up young children and take them to a room to sexually assault them. I saw children handcuffed to a pillar in the basement. They would be pushed and kicked. I saw Brother —— use a pool table stick to hit children if they would not have anal sex with him. Children were given cold showers then strapped. If I told any Brothers that another Brother tried to have sex with me, I would be strapped.” Former student Gerry Sirois described St. Joseph’s to Henton as “like Dachau with games.” Sixty years ago, David McCann felt alone and abandoned, bewildered and confused by the fact that his family didn’t protect him. “I understand now that they had no way to protect me, but it took me a couple of years to sort that one out,” he says. “But kids don’t have the skills set to deal with these things — a lot of adults don’t, either.” His mother tried to help. While visiting her son once at St. Joseph’s, McCann broke down and told her about the abuse he’d suffered. “My mom could wheedle anything out of me,” he says. But when she returned home to Kingston and raised the subject with her parish priest, she was threatened with excommunication if she continued to spread such horrible lies. So the abuse continued, and McCann tamped his emotions down. “I didn’t dream about it,” he recalls. “I basically buried it, closed the door, nailed it shut, plastered it over and let the memories … they were just there. “I didn’t deal with it at all. I didn’t talk to people about it. I think what it did was it made me not trust people. Here I’d been raised in the church where these priests and bishops and Christian Brothers and nuns were all these really righteous people, and then you see them doing something like that. I just learned really to not trust anybody.” McCann’s reactions to his abuse — his feelings of betrayal that his family didn’t help, his lifelong lack of trust in others and his attempts to bury his experiences rather than confront them — are not uncommon, says University of Ottawa psychology professor and clinical psychologist Elisa Romano, who specializes in childhood maltreatment and its impact on development. Studies, Romano said, suggest that men who have suffered sexual abuse don’t tell anyone about it for an average of 20 years. “Imagine living with something that is such an invasion of you as a person for so long.” Apart from the inherent power imbalance that gave the Brothers an upper hand over their wards, Romano adds that many of the boys at training schools such as St. Joseph’s and St. John’s would have faced the additional burden of not being listened to if they spoke out against their keepers. “All children are vulnerable, but these particular children may have been even more vulnerable because perhaps they wouldn’t have been believed, perhaps they would have been perceived as lying because these are boys who had significant behavioural challenges. “If you’ve been hurt by people that you trusted,” she adds, “whether it was people in this institution that were supposed to look out for you, or whether it was people in your neighbourhood or in your family, you start to develop a sense that it isn’t safe to be around people because they do hurt you, and that could definitely affect your ability to trust, your ability to make yourself vulnerable.” Gerry Belecque is among the St. Joseph’s alumnus who for decades buried his experiences there. The North Bay resident didn’t tell even his wife about it until McCann went public with his story in 1989, exactly 30 years after Belecque arrived at St. Joseph’s, and 26 years after he and his wife were married. “She grew up across the street and we’ve known each other since we were four,” he says, “so I expect she had been told by her parents that I ended up there. So I think she knew I was a bad boy and went somewhere, but I never told her where. “And I never told my parents what happened there, ever. I didn’t want anyone thinking I was a ‘faggot.’ Those were the words that were used: ‘faggot’ or an ‘abuser,’ and if you were abused, you were going to abuse. And as you get older, the more you learn about life, the less you want to say about it. That’s the way I felt — it was in the past, it was gone.” Belecque was just 14 when he was sent to St. Joseph’s in May 1959. An occasional truant from school who ran with a couple of older boys, he first got into trouble for stealing chocolate bars from a delivery truck when he was 13. He violated his parole by hitchhiking to Toronto one night with the same boys and acting as a lookout while they attempted to break into a store there. A judge decided that a stay at St. Joseph’s was in order. The abuse, Belecque recalls, began before he even arrived at St. Joseph’s. Wearing a leather jacket and Wellington boots, his hair Brylcreemed like Elvis, Belecque was handcuffed to the passenger door of his probation officer’s car for the drive to Alfred. Belecque says that as they drove along Hwy. 17, the officer began to fondle him. When Belecque tried to push the advance away, “then he grabbed my hand, wanting me to fondle him.” At a rest stop halfway to Ottawa, the abuse continued in a washroom, where Belecque, now handcuffed by the wrist to his probation officer, was forced to grab the PO’s penis while he relieved himself. Belecque thought that things had improved when he finally arrived at the school and was greeted by one of the Brothers, wearing a black frock and white collar. “I thought, ‘This is going to be easy,’” Belecque recalls. “‘This is going to be a cakewalk. I’m not in jail here, and there are no fences around it. It’s just a school.’ There’s a statue of St. Joseph out front, holding a child, and above the door are the words ‘Young men arise.’ “So OK, I’m a bad kid, and I’m going to go there and they’re going to straighten me out. I’m not going to give them any trouble. I’m here now and I’m going to do good. I always respected these people, so I thought ‘I’ll get what I give.’ So that’s my first impression.” Early on in his 16-month stay at St. Joseph’s, he hung back and watched others, but soon became involved in activities there, particularly athletics, competing in gymnastics and hockey. Boys who played on the school’s sports teams faced less abuse than others, but no one was immune. Belecque describes Brother Leo (Leopold Monette, who was eventually sentenced to five years after being charged with 21 counts of assault causing bodily harm, eight counts of indecent assault, one count of buggery and one count of gross indecency) as tough and unpredictable. “He was ex-army, and wanted the boys to excel at sports. But he was the kind of guy who was your friend one minute, and the next you didn’t know. He’d punch you in the face and you’d think, ‘Oh, shit, what did I do?’” While working in the kitchen once, handing out meals, Belecque was beaten for sneaking an extra slice of toast to one of the older boys. Belecque recalls another Brother beating boys with canes, hockey sticks and pool cues. “He’d let you have it, across the head or face, every time. He was a little wee runt of a guy, and he’d kick the shit out of you at the drop of a hat. He beat me up a few times, for like a ball going off the pool table.” That same Brother, Belecque says, ran the maintenance shop behind the school. The curtains were always closed and Belecque walked in one day to find one of the boys performing oral sex on the Brother. “That was my first encounter with that, and (the Brother) kicked the living shit out of me — and him, the boy, for not locking the door. He kicked us and beat us up. And you’d be walking around with a black eye and nobody would ask ‘Where’d you get that?’ Everybody minded their own business. No one wanted to get into anyone else’s stuff.” A week after that beating, Belecque was working in the shop when the same Brother approached him from behind and rubbed his penis against Belecque’s back for a few minutes. “I think I got off lucky,” Belecque says. It was Brother Gabriel (Aimé Bergeron, two years less a day for one count of indecent assault and one count of buggery) who was charged with sexually abusing Belecque. “And he was in charge of the altar boys,” Belecque says. “Give me a break. “What goes through these people’s minds?’ he wonders. “It happened, and you go ‘OK, it happened. That’s the way that person is.’ But after a while when I got out of there, I thought, ‘Why? Why do they do this? What’s the matter with these guys? And I can never get an answer in my mind. “I’d like to call people up who are abusers and ask them that question. What are you thinking? What goes through your mind when you’re doing that? Are you thinking that you’re helping these kids by showing them what sex is about? You’re religious, you’re Catholic, and you believe these people represent Christ or God on Earth or whatever, and then they do this, and you think ‘There is no God.’” Belecque returned to North Bay from Alfred in September 1960, 16 years old and a loner. Around the same time, reports of abuse at St. Joseph’s began to circulate in official circles. In an August 1960 letter to Ottawa archbishop M.J. Lemieux, Archie Graham, deputy minister of Ontario’s Department of Reform Institutions, wrote, “We know that you will appreciate our desire to take the necessary action before the growing number of complaints received by us from parents, welfare workers and others reaches such a magnitude that the matter becomes public knowledge, in which event the school, this department, and the Church can only suffer.” And still the abuse continued. Back in North Bay, Belecque married and had two children, but his anger remained. He drank, did drugs and gambled. This was not an uncommon outcome for former students. According to The Recorder’s Report concerning abuse at the schools, “The men as a group are bitter, poor, marginalized and lack self esteem.” Upwards of 80 per cent of them maintained that some or all of the problems they faced after leaving training school were related to the abuse they suffered there. It wasn’t until the mid 1970s, when he decided to finish high school and then earn his BA in sociology and psychology, that Belecque recognized the source of many of his troubles. “I took those subjects because I wanted to know what was going on in my mind,” he says. “It was personal. And a lot of those things in the books applied to me. I was neurotic, I was psychotic. “So that’s when I started to see a psychiatrist.” But he told no one else, not even his wife, out of embarrassment and a fear that others might think him a “weirdo.” David McCann similarly did not deal with the abuse he suffered. Released from St. Joseph’s after two years, he moved into a summer cottage on Lake Ontario, just west of Kingston, where he lived alone for two years before returning home to his parents’. “I didn’t deal with it. I just buried it,” he says. “As a 12-year-old when this happens to you, you just go, ‘What did I do to deserve this?’ But it took years before I figured out that I was in no way to blame, that the system was to blame.” Part of that realization came in 1989, when he saw a news report on TV about the then-emerging story of child abuse by the Christian Brothers of Ireland in Canada, at Mount Cashel Boys School, an orphanage in St. John’s, Newfoundland. The news floored him. He wasn’t alone, he realized. And in the case of Mount Cashel, it looked as though something might be done about it: Newfoundland interim premier Tom Rideout had appointed a Royal Commission to investigate. And so McCann, who by coincidence had been speaking with Toronto Star reporter Darcy Henton about an unrelated story, came forward with his allegations. Other victims surfaced, and McCann and a few others, including Belecque, helped found Helpline, and advocacy group for former students of St. Joseph’s and St. John’s. Rather than pursue a class-action lawsuit, the group elected to work with the religious groups that ran the schools, the archdioceses of Ottawa and Toronto and the Ontario government to reach a reconciliation agreement with the hundreds of victims who came forward. Ultimately, although the Christian Brothers of Ontario, who ran St. John’s, refused to participate, the other sides agreed to a $16-million settlement. Reports varied, but most recipients received in the neighbourhood of $20,000. A 1996 story in the Citizen looked at what some of the former students did with their settlement. Some opened businesses and at least one had dental work done, to replace the teeth that the Brothers had knocked out. Still others spent theirs on drugs or alcohol. For many, though, the settlement arrived too late: 32 of the victims had committed suicide. McCann, meanwhile, continued to seek apologies. As part of the reconciliation agreement, the Ottawa and Toronto archdioceses apologized, with Ottawa archbishop Marcel Gervais doing so at a noon mass at Notre Dame Cathedral in April 1996. For some, the act helped. McCann at the time said, “It puts a lot of devils to rest.” McCann also found some unexpected encouragement during the mass. Seated in the pew in front of him were a woman, a man and a young girl, perhaps five or six years old. The girl, McCann recalls, repeatedly turned to her mother to ask why the man behind her was crying. “Now there’s a part of the Catholic mass where you turn to your neighbour and greet them,” says McCann. “And the mother turned around and looked directly at me and said, ‘Mr. McCann, I know who you are, and I want to thank you and all the men with you. You’ve made the world a safer place for my child.’ And if you want validation for whether it was worth doing, in that one moment that woman told me that everything we did was worthwhile. There’s another child who won’t go through what we did.” But others were not as comforted. One former student, Paul Gagnon, stood and shouted at Gervais: “I don’t want an apology from you. I want an apology from the brothers that ruined my life. I want an apology from those two dogs — those two pedophiles.” Another former student, Jimmy Toal, confessed his circumspect resignation. “All of this brings back memories,” he told the Citizen at the time. “It’s never really done.” As part of the agreement, Ontario premier Mike Harris was to “propose an all-party resolution in the legislature, apologizing for and condemning the abuse.” He refused, however, instead leaving the apology to attorney general Charles Harnick to deliver while Harris was out of town. McCann responded by taking Harris to court. Ultimately, it was premier Dalton McGuinty who, in 2004, offered an apology on behalf of the province. “I don’t like all of Dalton McGuinty’s policies,” says McCann, “but on 10:30 on Election night, after he’d been elected, his senior aide called me on the phone and said ‘I just spoke to Dalton, and he asked me to ask you to give him 60 to 90 days to assume the reins of power, and he will rise in the legislature.’ And he did rise in the legislature and spoke, not only as the premier, but he begged the indulgence of the House after everybody else had spoken, and he rose and spoke as a Catholic and as a father. “I give the guy a lot of credit. The entire time he spoke, he looked at us, and the second time he spoke, he talked about sitting at his breakfast table and looking at his 12-year-old son, and he said, ‘I can’t imagine that happening to my son, and as a father and a Catholic, I apologize. I’m appalled.’” In 1990, as his public allegations began to snowball, McCann and 15 other survivors hand-delivered a letter to Angelo Palmas, Apostolic Pro-Nuncio to Canada, at his Rockcliffe residence, asking the then-Pope, John Paul II, for an apology. McCann never received a reply. Two Popes later, in 2017, McCann travelled to the Vatican where, at the behest of the Pope, he was seen by Father Hans Zollner, professor of psychology and current president of the Centre for Child Protection at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. The pair spoke for a couple of hours. “(Zollner) was hopeful that Francis would apologize,” recalls McCann, “but he was very clear that he had no authority to speak for the Pope.” Over the years, popes have spoken on the issue of abuse of minors by clergy. In a 2002 address to U.S. Cardinals, Pope John Paul II said, “People need to know that there is no place in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young.” In 2008, Pope Benedict apologized for the sexual abuse of children by priests and clergymen in Australia, noting, “I am deeply sorry for the pain and suffering the victims have endured and I assure them that, as their pastor, I too share in their suffering.” Benedict was criticized, however, for delivering the apology to a group of Catholic bishops, seminarians and novices, rather than victims. Two years later, at a mass at Westminster Cathedral in London, Benedict again acknowledged and somewhat apologized for the suffering caused by the church, saying, “I think of the immense suffering caused by the abuse of children, especially within the church and by her ministers. Above all, I express my deep sorrow to the innocent victims of these unspeakable crimes … “I also acknowledge with you the shame and humiliation that all of us have suffered because of these sins.” And last August, in a 2,000-word letter addressed to the “People of God,” Pope Francis admitted that the Church “showed no care for the little ones; we abandoned them.” This came after a U.S. grand jury confirmed that more than 1,000 children had been sexually abused by “predatory” priests in Pennsylvania while church officials failed to discipline offenders and often covered up incidents. “Let us beg forgiveness for our own sins and the sins of others,” the Pope added. For some, though, any apology now is simply too little too, late. Gerry Belecque long ago lost his faith in God, and has avoided church since leaving St. Joseph’s. “When there are weddings, I sit outside,” he says. “When there were baptisms, I always stayed outside.” On occasions when felt he had no choice but enter, such as at his parents funerals, he stayed at the back. “If the apology comes from the people who did it, that’s a different thing. But if it comes from those who knew that they did it but didn’t do anything, big deal. It doesn’t make a damn difference to me if the Pope apologizes. It’s just words. They don’t give a goddamn, and they’re still doing it. So apologies don’t mean anything. “You never get closure,” he adds. “It took me a long time to get over it. Right now I’m not seeing anybody, but I’ve got one foot in the grave, maybe.” Yet McCann persists. “There aren’t many Don Quixotes in the world, and I don’t mind tilting at windmills. It’s a chance to continue to make a difference in the world. It gives meaning to going out there and saying it doesn’t hurt to apologize. It wouldn’t hurt Francis to stand on the balcony in St. Peter’s Square and say he’s sorry. He doesn’t have to come to Canada to do it. It would carry just as much weight. For a lot of people, just the words are enough.” St. Joseph’s Training School for Boys was officially opened on Aug. 6, 1933, by Les Frères des Ecoles Chrétiennes d’Ottawa. In 1973, the Ontario Ministry of Correctional Services assumed operation of the school, which was renamed Champlain Training School. It closed in 1984. St. John’s closed in 2003. Contact: bdeachman@postmedia.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.