|

What happens when a priest is falsely accused of sexual abuse

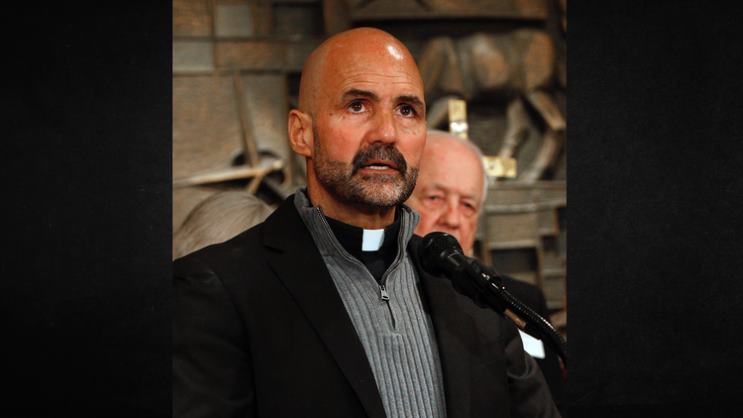

By Michael J. O’loughlin

Until last year, online search results for the Rev. Gary Graf would include stories about his liver donation to a parishioner, his scaling a border wall so he could understand more intimately the experiences of his immigrant parishioners and a hunger strike he staged to draw attention to the plight of Dreamers. Today, however, the top results relate to Father Graf’s removal from ministry last August following an accusation that he inappropriately touched a minor. That allegation prompted the Archdiocese of Chicago to remove Father Graf from ministry and contact civil authorities, setting off multiple rounds of investigations—including a criminal trial—that ultimately cleared him of any wrongdoing. As Holy Week begins, Father Graf is back ministering, but his story illustrates the challenges facing priests who are falsely accused at a time when hundreds of true stories of horrific abuse dominate the news. Last May, the Archdiocese of Chicago announced that three parishes in the city’s West Side would merge into one, José Luis Sánchez del Río Church. Father Graf, who has spent much of his priestly career in Hispanic parishes, was later appointed pastor, in part because of his previous experience leading parishes through mergers. He knew the challenges that accompany such endeavors, especially when it comes to the uncertainty parishioners feel over such moves, and so he was eager to get to work. Father Graf’s story illustrates the challenges facing priests who are falsely accused at a time when hundreds of true stories of horrific abuse dominate the news. But just a few weeks after he arrived at the parish, which includes a church where he ministered more than three decades earlier, he received a call from the archdiocese. An allegation of misconduct involving a minor had been made against him. Then on Aug. 25, parishioners received a letter from Cardinal Blase Cupich, the archbishop of Chicago, informing them that Father Graf had been placed on leave “pending the outcome of an investigation into an allegation of code of conduct violations involving a minor.” Father Graf could have no contact with church officials, including other priests, and he would need to retain his own legal counsel. The accuser, a 17-year-old who worked part-time at one of the three churches in the parish, told WGN on Aug. 27 that Father Graf had touched his shoulder and back, asked him if he needed a ride home from work and then offered him a free car. The accuser also said the church receptionist had called him to say the priest found him attractive. In an interview with America on April 11, Father Graf said parishioners routinely inform him about all sorts of items—cars, furniture, bicycles—that they want to give away, asking him if he knows anyone who might be in need. When he learned about an old used car that someone was trying to give away, he said, he asked the part-time employee if he would be interested in it. During the conversation, Father Graf said, he placed his hand on the young man’s shoulder, something he says he does regularly when talking to people. Father Graf said he understood the need to take allegations seriously and then to conduct independent investigations. He added that he regularly makes sure that staff and volunteers have rides home when meetings or shifts end. As for the call from the receptionist, Father Graf said it never happened. During a criminal trial, the receptionist herself denied ever making the call. As the investigations wore on, Father Graf said, the silence haunted him. “The silence, I didn’t know what that meant. You don’t know if there are other accusations,” he said. “What else are they hearing?” Still, he said he understood the need to take allegations seriously and then to conduct independent investigations. “We have no one to blame but ourselves because we did it wrong for years,” he said. “Instead of believing the child in our midst, which is most important, we...listened to the priest.” “We have no one to blame but ourselves because we did it wrong for years. Instead of believing the child in our midst, which is most important, we...listened to the priest.” Eventually, the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services determined the allegation was not credible. Chicago police conducted their own investigation and decided to bring charges. After consulting a lawyer, who took the case pro bono, Father Graf said, he paid for a polygraph test, which he says showed he was not lying about the allegations. He said the trial was challenging, but parishioners showed up to support him, and a judge ruled in January that he was not guilty. With two civil investigations complete, the archdiocese then conducted its own investigation. Earlier this month, it determined the allegation was not credible. After meeting with the accuser and his family, the cardinal told Father Graf that he would return to ministry. Experts say precise figures related to the number of U.S. priests falsely accused of abuse are not available. But the annual report published by the National Review Board, the body that advises U.S. bishops on child sex abuse, suggests that while false accusations are rare, they do happen. The 2017 report, for example, shows that investigations of 182 allegations of abuse that were made before July 1, 2016, deemed 107 of them credible and another 60 in need of more investigation. But 13 were deemed “unsubstantiated” and two were found to be “obviously false.” “False claims of sexual abuse are remarkably low,” Zach Hiner, executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, told America. According to the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, U.S. dioceses “are to report an allegation of sexual abuse of a person who is a minor to the public authorities.” In Chicago, allegations are reported to civil authorities and an internal investigation occurs after civil authorities release their findings. “False claims of sexual abuse are remarkably low,” Zach Hiner, executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, told America. “That is not to say they don’t happen, as [Father Graf’s] case illustrates. But most people coming forward with allegations of sexual abuse are telling the truth.” Mr. Hiner said that while SNAP recognizes the “terrible situation” in which falsely accused priests find themselves, it is a sign of hope that civil investigations are capable of unearthing the truth. He added that SNAP “spend[s] our energy focusing on victims.” Priests falsely accused of abuse are often reinstated to ministry, though their paths differ and challenges sometimes remain. Father Graf is eager “to be with God’s people again and listen to them, walk with them, accompany them.” Last year, Msgr. Edward Sacks, a priest in Pennsylvania, was reinstated after being “cleared by an independent investigation” that found “no abuse of any kind occurred, and that it was an erroneous allegation,” according to the Diocese of Allentown. In 2016, a South Dakota priest, the Rev. Joseph T. Forcelle, was removed from ministry for two months after an allegation was leveled against him in Minnesota. When law enforcement declined to press charges, church officials conducted their own investigation. Based on those findings, the diocesan review board “concluded that the facts asserted do not substantiate this allegation,” and Father Forcelle was returned to ministry. And a high-profile case involving a priest accused of abuse engulfed the Saint Louis area beginning in 2013. A priest of the archdiocese, originally from China, the Rev. Joseph Jiang became close to a Catholic family, sharing meals, occasionally spending nights at their home and at one point offering to buy a house they could rent while saving for a down payment. Shortly after he realized he could not afford a home and told the family, an allegation that he sexually abused one of the daughters was leveled against him. Later, another family made an allegation that Father Jiang abused their son. Eventually, the priest was cleared of abuse—he also received an apology from SNAP over statements that he said defamed him—and he was returned to ministry. But last year, after the archbishop assigned Father Jiang to a parish that is also home to a school, a number of parents expressed concern and the assignment was withdrawn. “Although false accusations are terrible, they can’t possibly compare with being victimized, being sexually assaulted and molested, especially by a priest,” Father Graf said. The attorney representing Father Jiang told Saint Louis Magazine that while most allegations of abuse against priests are found to be credible, that “doesn’t mean you can just falsely accuse a priest and there be no consequences, because once the accusation is made, it cannot be unmade.” “When the case gets dismissed,” Paul D’Agrosa continued, “people say, ‘He had a smart lawyer.’ And if you go to trial and a jury finds you not guilty, it’s ‘He beat the system.’ That’s what angers me about the second case. Not the first. Father Jiang bears some responsibility for that. He was naïve—the days are gone when a priest sleeps in a home!” Father Graf stood at the altar with Cardinal Cupich on Tuesday, concelebrating the Chrism Mass, and parishioners have said they are happy he is returning to work. He said that instead of focusing on his experience during the past few months, he is eager “to be with God’s people again and listen to them, walk with them, accompany them.” Despite the lengthy investigations and the uncertainty he felt as the weeks turned into months, Father Graf said he had faith in the system and that he understood the need for a thorough investigation that included not being in touch with church officials. “In the past, we did not put the child first,” he said. “They didn’t listen to the child and pull the priest out of ministry and find out what was going on. So I’m elated that we’re at this point. I lived through it, and it was very, very, excruciating. And yet it’s the way it’s got to be.” In a letter to parishioners announcing Father Graf’s return to ministry, Cardinal Cupich thanked them for their “great patience as each jurisdiction has completed its process.” He pointed to archdiocesan policies that “call us to do everything possible to restore the good name of priests when the process has determined the allegations to be unfounded. This, too, is a matter of justice.” Some priests who have been cleared following allegations of abuse have sued their accusers in an effort to help restore their reputations—stories about allegations often have longer digital shadows than those that exonerate—but Father Graf said he has no plans for that. Instead, he said the focus should be on victims of sexual abuse. “Although false accusations are terrible, they can’t possibly compare with being victimized, being sexually assaulted and molested, especially by a priest,” Father Graf said. “It’s a terrible, terrible sin that has devastated the church because it devastated the most important people in our church, which are children. And in the past, we did not put the child first.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.