|

More Americans than ever are leaving the Catholic Church after the sex abuse scandal. Here's why.

By Lindsay Schnell

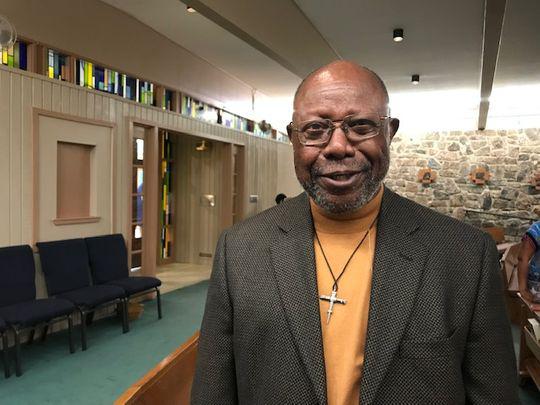

[with video] On Palm Sunday, Barbara Hoover exited Brougher Chapel with a palm frond in her left hand. The 76-year-old retiree sized up the church in front of her and sighed, visibly upset. “I don’t know why I’m still here,” she said, throwing her hands up. “I don’t know why I still go. I guess the ritual.” In Portland, Oregon, Norma Rodriguez, 51, hustled up the steps of St. Mary’s Cathedral of Immaculate Conception, eager to get a good seat before the service started. A lifelong Catholic, Rodriguez attends Mass weekly, praying for everyone she knows. She hasn’t been deterred by the sex abuse crisis that’s engulfed the Catholic Church for the better part of two decades. It’s not her place to pass judgment, Rodriguez said. “This whole thing, it makes me pray more,” she said. “It just makes me pray for humanity, makes me pray for forgiveness.” In Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Sara and Nathan Hofflander brought their three young daughters to Palm Sunday Mass, then joined the bustle of people chatting and enjoying a hot meal during St. Lambert’s yearly parish dinner. Plates filled with turkey and potatoes. The parents corralled their girls – ages 5, 3 and 1 – and found a spot near a window. Sara Hofflander, 32, grew up Catholic and Nathan Hofflander, 40, joined the church in 2011. The fallibility of clergy doesn’t faze him. “We are all broken in some way,” he said. “We’re not all perfect.” The Catholic Church in the U.S. is at a crossroads. As millions of devout followers filled the pews this Easter season to celebrate the religion’s most important holiday, others hovered at the door, hungry for community and spiritual guidance but furious at the church’s handling of the decades-long sex abuse crisis that’s resulted in young children being raped and abused by priests who were often protected by their superiors.Seven months after a damning grand jury report in Pennsylvania revealed that 1,000 children had been abused at the hands of more than 300 priests, and as state attorneys general across the nation investigate the church, a Gallup poll published in March found that 37% of U.S. Catholics are considering leaving the church because of the sex abuse crisis and the church’s handling of it. That’s up significantly from 2002, when just 22% of Catholics said they were contemplating leaving their religion after The Boston Globe published an explosive series that initially exposed the abuse and subsequent cover-up.On Palm Sunday, the start of Holy Week, the USA TODAY Network sent 13 reporters out to parishes across the country to talk with dozens of Catholics about their faith and the scandal that has bankrupted churches after million dollar settlements, exposed thousands of accused priests and left unknown numbers of victims struggling to rebuild their childhoods, families and spiritual lives. Reporters visited white, black, Latino and Asian majority churches in cities and rural areas from California to New York, from Florida to Guam, as priests across the world spoke of repentance, forgiveness and, ultimately, new life.In the Bible, Jesus’ crucifixion gives way to death and mourning. Three days later, resurrection comes, along with the hope of new beginnings. Many Catholics – most of whom were raised in the faith and can’t imagine celebrating major milestones without it – want the church to have a similar rebirth. But as church leaders, led by the pope in Rome, continually refuse total transparency and justice for victims, some wonder if that renewal will ever come. In El Paso, Texas, Maria Pacheco normally watches Mass from home, when she tunes into a Spanish-language TV station. But on Palm Sunday, a friend offered her a ride to church. Pacheco attended the first Mass of the day at St. Paul the Apostle, a mostly Hispanic Catholic parish with services in English and Spanish. Pacheco’s seen a lot in the news about the abuse crisis. She finds it abhorrent. The scandal hasn’t driven Pacheco, 76, away from church, but she does have doubts. “I think it has made me lose trust in priests in general,” she said in Spanish. “Sometimes I wonder, if I were to come and say confession, would he have committed worse things?” Questioning the Catholic ChurchAcross the country in Nashville, Tennessee, as the 8:30 a.m. Palm Sunday Mass let out, well-dressed Catholics streamed out of the Cathedral of the Incarnation carrying palm fronds in their hands, some tied and braided to look like the Christian cross. Maria Michonski, a 24-year-old student who said the clergy sex abuse crisis has contributed to questions she has about the Catholic Church as an institution, was not among the faithful. A student at Vanderbilt's Divinity School, Michonski been trying to figure out for several years how her faith – which she learned as a child – fits into her adult life. Michonski grew up in the Nashville diocese, went through the city’s Catholic school system and studied theology as an undergraduate at Saint Louis University. She started to have a contentious relationship with the church five years ago when she came out as queer. For a while, Michonski stopped practicing all together. Now she attends Mass sporadically, divided between her desire to help make the church better while wanting to distance herself from the sex abuse crisis. But she said she won't contribute financially. “I don’t tithe to the diocese, and that is intentional,” Michonski said. “Continuing to amass power and wealth inside a system that is so clearly broken feels very unconscionable to me.” The more stories she sees about clergy sex abuse, the angrier she gets. But she can’t walk away entirely. “On good days it feels like it’s possible to make some change in the church and on bad days it doesn’t,” she said. “And the bad days are often linked to these big news stories where you just see how deep the power, abuse and corruption lie in the church.” ‘I felt spiritually abandoned’For Maureen Roden, the pull of tradition wasn’t enough. Roden, who lives just outside of Washington, D.C., grew up in “your typical Irish Catholic family.” She and her three siblings were raised in the church, attending Mass regularly. When she married – her husband was raised Protestant – and started having children, she decided they’d be baptized Catholic, too. Years later, on the morning of Jan. 6, 2002, her two girls were dressed in their Sunday best and eating breakfast when Roden saw The Boston Globe’s story. Appalled, she told her husband they wouldn’t go to Mass that day. She hasn’t been back since. “This was my moral authority, this is who I went to for moral direction,” said Roden, now 53. “I felt so angry and so betrayed. Not only that there were pedophiles in the church, but that they knew about it and covered it up. “I could not bring my children to that church and say, ‘These are your leaders.’ I couldn’t put my money in the collection basket. I felt spiritually abandoned.” She and her husband church-shopped for a few months, but everything felt off. Members of the Unitarian Church wearing sweats to Sunday service bewildered her. When she suggested they try a local Jewish synagogue, her husband gently asked if she was ready to give up her 63 Christmas albums. Ultimately, they settled on a Presbyterian congregation, but it never felt quite right. Roden missed the format and tradition of Catholicism, a religion where anyone can attend Mass on any given day, anywhere in the world, and hear the same order, prayers and liturgy. She found comfort in that structure, just like she did with familiar Catholic hymns. Without them, she felt lost. “It didn’t stick,” she said sadly. “These weren’t my people.” Dismayed to find out there’s no real breaking up with the Catholic church – “once you’re baptized, they consider you in forever,” she said – Roden spent the next 16 years disgusted by what Catholic leaders had done. Some of her anger, she thought, might have come from her previous work as a pediatric nurse: She understood the toll sexual abuse can have and knew recovery often takes many painful years. She didn’t worry that in holding others accountable, she was trading away her shot at salvation. Instead, she thought often about the mantra, “What would Jesus do?” She knew he wouldn’t tolerate anyone hurting children. “As a society, why should we expect any less from the pope than we do from the principal at our children’s schools?” Roden said. “If a teacher sexually assaulted a child, that person would be fired immediately and the police would be called.” Roden’s not sure if she’ll ever be able to re-join the religion she grew up loving. She wonders sometimes what would need to happen for her to attend another Mass, or to put money in the collection plate. Maybe she could get there, she said – but not before major change. Holding strong to faithIn other parts of the country, many Catholics acknowledged their unwavering beliefs as well as the hurt their spiritual leaders have caused. In the U.S. territory of Guam, Johnny Villagomez lost trust in the Catholic priests who were named multiple times in Guam’s clergy sex abuse revelations since 2016. But he and his wife, Linda, have not lost faith in God or the church. “Who else is going to take care of the church if not us, the believers?” said Villagomez, 75, a retired wildlife conservation officer. That same sentiment was expressed in Atlanta, where on a rainy Palm Sunday, parishioners filed into the sanctuary at Most Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church collecting palm leaves from a wooden table set up in the lobby area. Next to the leaves, a white basket overflowed with packets of the morning’s scripture reading: Luke 23:1-49. That passage details Jesus’ crucifixion, including when Jesus cries out to God, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.” Attendance at this majority black church rises each Easter holiday season, said the Rev. Desmond Drummer. Allegations of widespread sex abuse throughout the Catholic Church haven’t changed that. “Sometimes we need to remind folks … you are innocent, you are a beloved child of God,” Drummer told his congregation during the service. To Richard Jones, who has attended Most Blessed Sacrament for the past 16 years, the abuse crisis signals a need for greater engagement, not abandonment. “I have lots of concerns, and that’s why I stay involved,” said Jones, 79, a retired consultant. “I’m not totally enamored with where we are. But I’m not so disassociated that I’m ready to walk away.” Younger members feel that way, too. In Tempe, Arizona, about 60 people gathered at the All Saints Catholic Newman Center on the Arizona State University campus. One of the congregants was 29-year-old registered nurse Angela Jungbluth, who has been Catholic since birth. The sex abuse scandal “shocked” her, but Jungbluth said she never questioned her commitment to the Catholic faith because of it. “I think the truth runs deeper than the sins of really evil men,” she said. “My faith is not held together because people are good, it’s more because God is good.” One man showed up to Mass in an ASU tank top, gym shorts and sandals while two women arrived wearing traditional Catholic veils covering their heads. The Mass began with the vague smell of frankincense and a processional into the church, where all members of the congregation held palm branches in honor of Jesus' triumphant arrival to Jerusalem. In South Dakota, Mary Glenski claimed the problems with the church – specifically with the Sioux Falls diocese – are in the past. The problems belonged to "that time period,” she said, adding that in regard to the recent allegations, "in some cases, it's been so long ago that people that come with accusations may or may not have accurate memories.” Despite reports of abuse and the release of names by South Dakota’s two dioceses last month, the 88-year-old retired teacher and South Dakota lawmaker said she won’t be revoking her membership or her financial support. Still, the constant stream of new accusations is challenging for the survivors of clergy abuse. The ongoing crisis is a reminder not only of their own suffering, but of the church’s failure to protect them. Michael Vanderburgh, a father of four in Dayton, Ohio, struggled for years to reconcile the abuse he endured at the hands of a priest with his decision to remain a Catholic. He ultimately chose to separate the religion he loved from the church leaders who betrayed him. “The church is not about the humanity of its individual actors,” said Vanderburgh, 47. “It’s focused on God. It’s not focused on the individuals who make it up.” Over time, Vanderburgh did more than forgive the church. He went to work for it. A few years ago, he led the largest-ever fundraising campaign at the Archdiocese of Cincinnati, bringing in more than $100 million. He’s now executive director of another Catholic charity, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, in Dayton. While Vanderburgh said he thinks the church has made strides toward strong safeguards for children, he doesn’t mind that church leaders are taking a beating for their past failures. Catholics, especially abuse survivors, deserve a full accounting, he said. “There is still some reckoning to do with the past,” he said. Church leaders acknowledge hurt, promise changeIn Southern California, church members said leaders know they can’t hide from the abuse, or from talking about it. At St. Bridget Chinese Catholic Church in central Los Angeles, about 70 people gathered for the English Mass following a service in Cantonese. Potted palm plants wrapped with purple tissue paper decorated altars inside. Outside, elderly members socialized in Cantonese, ate oranges and read community newspapers. Inside the church’s foyer, pamphlets on preventing child abuse sat on a table. During Mass, one of the group prayers highlighted National Child Abuse Protection Month, calling for renewed commitment to supporting children. “They probably provide a lot more training than we ever feel like we needed to make sure it doesn’t happen,” said Peter Chan, 44, a sales manager and lifelong Catholic. In Nashville, the Rev. Edward Steiner, pastor of the Cathedral of the Incarnation, tries to be frank with his congregation. "A person that I’ve kind of got a great rapport with, but who's also very blunt and direct, just simply said, 'Father, I don’t know that I can take anymore. Could you please give me a reason to be a Catholic?' " Steiner said. Since the most recent wave of allegations, Steiner said he’s heard from Catholics who are victims of abuse, but not at the hands of the church. Hearing about the church scandal often triggers past trauma and brings with it a flood of questions. Catholics, Steiner says, are not looking for reasons to leave, but for reasons to stay. Parishioners aren’t the only ones searching for answers. Future leaders are, too. As Rodriguez walked inside St. Mary’s Cathedral in Portland, Saul Medina handed her his navy blazer, and asked her to save him a spot. Born in Guadalajara, Mexico, Medina felt a call to the priesthood roughly 10 years ago, shortly after he started a career in finance. Now 36, he’s studying at Mount Angel Abbey just south of Portland. Stories of clergy abuse have both infuriated him and left him heartbroken. It’s also emphasized the responsibility he’ll have one day, when he leads his own congregation. A responsibility, he said, not just to live his life with integrity and hold other Catholic leaders accountable, but to create an environment where everyone feels comfortable speaking out if something seems amiss. The church is supposed to bring people closer to God, Medina said, and the only way to do that is to adopt a zero tolerance policy. As he climbed the steps to walk into Palm Sunday Mass, Medina had a request for anyone questioning the future of the Catholic Church. “Pray for me,” he said. “Pray for us. Pray for us that we can tell the truth.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.