Abused by Missionaries

By Lise Olsen and Sarah Smith

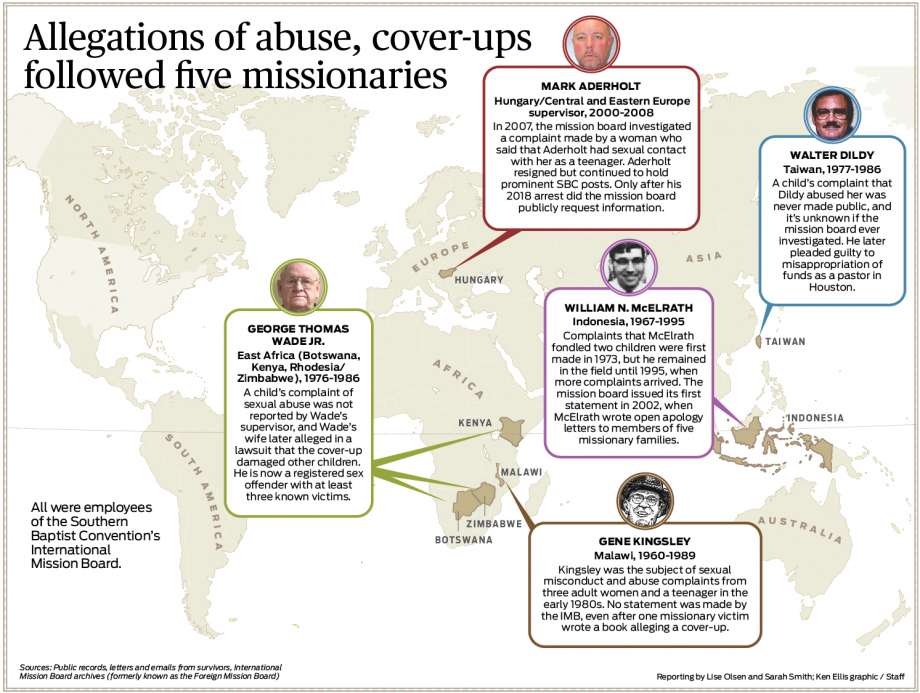

A supervisor met once privately with the girl, who was attending boarding school in Johannesburg, and later consulted leaders based 7,500 miles away at the Richmond, Va., headquarters of what's now called the International Mission Board. Wade promised to stop, the supervisor said. His daughter said she was told to forgive Wade and was sworn to secrecy. No one told Wade’s wife, also a missionary, what he had done, court records show. His daughter was never again asked about the abuse, which continued, even after she attempted suicide at 15. “I felt stupid for having told anything to anybody,” she later testified. “The concern was for my father. ... It didn’t matter what happened to me.” The practice of the Southern Baptist mission board — the world’s largest sponsor of Protestant missionaries — has been for years to keep misconduct reports inside the hierarchy of the organization, a Houston Chronicle investigation reveals. The board is a massive charitable organization that as of 2018 fielded more than 3,600 missionaries and “team associates” overseas and managed an annual budget of $158 million or more, nearly all tithes from members of churches that belong to the Southern Baptist Convention. By the time Wade’s wife, Diana, finally learned of the cover-up, her husband had abused three children, causing what she described in a letter to her employers as the “most shattering and devastating time in my life.” Wade was prosecuted and went to prison for child abuse in Alaska. He was later arrested again in Georgia in 1997 and remains a registered sex offender. The Chronicle found a long trail of alleged cover-ups involving sexual misconduct or crimes committed abroad by a small number of Southern Baptist missionaries, all salaried employees of the mission board. Collectively, five men were credibly accused or convicted of abusing about 24 people, mostly children, court records, documents and interviews show. These new revelations come as the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest and most influential coalition of Protestant churches in the United States, is wrestling with a burgeoning sexual abuse crisis as it prepares for its national meeting in Birmingham, Ala. The missionary cases followed a similar pattern: Leaders were informed of alleged abuse but made no public statement to immediately alert others and often delayed or took no action to remove an accused offender. In at least three of five cases, survivors allege that the board’s failure to act gave perpetrators the opportunity to harm more people, according to court records, correspondence and interviews. Nationwide, other major Protestant groups have hired consultants to devise new policies that better fit a modern world with an enhanced awareness of the dangers of charismatic predators who misuse charitable fronts to hide child abuse, sex tourism, child pornography or pedophilia. But the practice of relying on church insiders to privately investigate allegations of sexual abuse involving missionaries still prevails at the IMB, though leaders repeatedly promised to address failures and enact reforms. Copies of policies, letters, court documents and interviews show that the board refused to change despite being repeatedly confronted by survivors and their families: ? In 1992, Wade’s wife, the daughter of a Southern Baptist pastor, reluctantly filed a lawsuit in Richmond, claiming the board failed in its promise to protect her children. A jury awarded $1.5 million in damages. But the board appealed, the Supreme Court of Virginia overturned the verdict and the board did not alter its policies. ? In 2004, the IMB established a hotline for abuse victims after another major scandal erupted over ex-missionary William “Mac” McElrath, who publicly admitted to molesting his colleagues’ children during decades in Indonesia. Since then, the board has received 100 calls to the hotline, spokeswoman Julie McGowan told the Chronicle. But McGowan said she could not provide further information or statements about related board action. ?In an email addressed to McElrath’s victims, the board’s attorney promised to handle future allegations openly. “We want to affirm our commitment to promptly and completely investigate any new charges of sexual abuse made against missionaries and to terminate and publicly expose any missionary found guilty of such abuse,” the letter from June 2002 says. But the board broke that promise only five years later, its own records show. That’s when Anne Marie Miller, of Fort Worth, first told the IMB that missionary Mark Aderholt allegedly initiated sexual contact with her when she was a teenager, according to affidavits. The IMB substantiated her complaint but said nothing publicly and did not contact police.

Current IMB policy calls for “zero tolerance” of child abuse and asks for anyone who has personally experienced abuse or sexual harassment to “bring this conduct into the light by means of a secure report to IMB leadership.” The policy still does not require officials to report child abuse to police, though that soon could change. In 2018, the IMB’s outgoing president formed a task force and hired a Minneapolis-based law firm, Gray Plant Mooty, to review its conduct and policies after Aderholt’s arrest.

In late May, the firm provided an update, recommending sweeping changes to how the IMB handles sexual abuse allegations — including reporting allegations to law enforcement in the United States and abroad even if the law doesn’t require it. The IMB’s current elected president, Paul Chitwood, pledged that the board would adopt those recommendations, but he did not provide a timeline. It’s unclear when or whether the mission board will release a full report on past failures, including who could have been complicit in enabling alleged abusers over decades. In addition to the president, the IMB is overseen by a board of trustees, who also are sworn to secrecy under its policies. Mission board leaders turned down requests for an interview; McGowan responded to questions via email. “IMB leaders believe it is absolutely critical for the IMB and for churches to have guidelines related to child abuse and sexual harassment, which underscores IMB’s commitment to a serious, rigorous examination of its policies and practices,” she said.

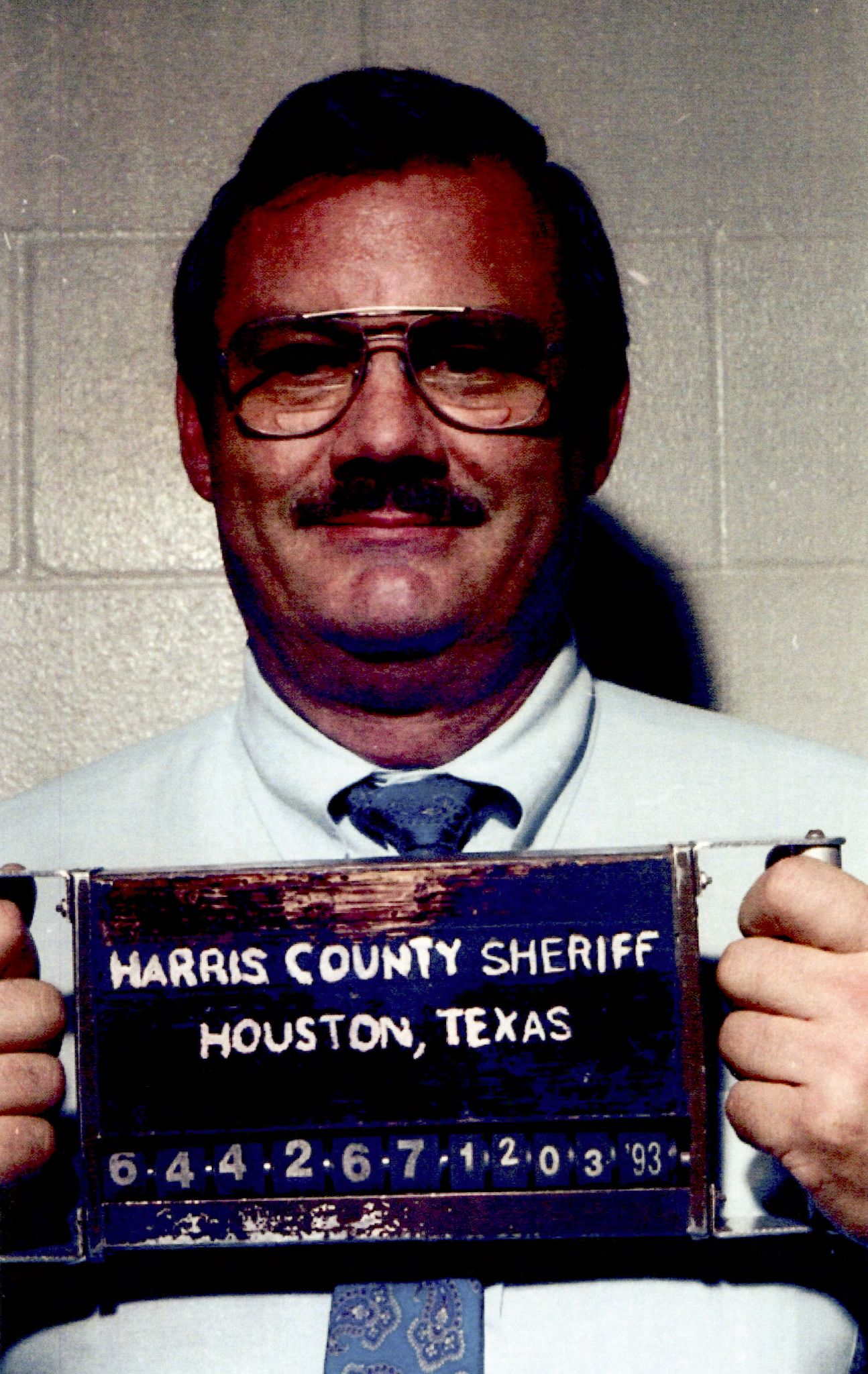

Allegations in Africa The board has never responded publicly to accusations of a cover-up of alleged abuses by a Texas-based missionary described in a 1993 book written by another longtime former missionary, Dee Ann Miller. Miller, now 72, was born into the Southern Baptist world. Her father and grandfather were both pastors. By age 10, she knew she wanted to be a missionary, one of the few leadership opportunities open to women. She and her husband, Ron, were thrilled to be appointed to Malawi in 1978. There she met Gene Kingsley, a missionary since 1960. She visited his house in May 1984 and he hugged her, as usual. Then, Kingsley “assaulted me, quickly and skillfully pulling me a foot off the floor, continuing to tighten his arms as I struggled and he groped until I yelled, commanding him to put me down,” Miller said in an email to the Chronicle. PART 1: Southern Baptist sexual abuse spreads as leaders resist reforms Miller, who had worked with sexual predators as a nurse, reported him to other mission personnel. Nothing happened. Two years later, she decided to make a written complaint, after learning others in her “mission family” also had reported being inappropriately touched or worse. Her complaint went up the chain of command to leaders in Richmond. Kingsley was permitted to resign rather than be terminated, she said. Miller described in interviews and in her book how two other women, as well as a teenaged girl, also complained but said those reports were initially ignored and inadequately investigated. Miller said she was told there was a policy change, but she didn’t see any evidence of it. “I pushed for people to take action,” Miller said. “Nobody did anything.” Kingsley died in Texas in 2016. Some of the same supervisors took a similar approach when George T. “Tom” Wade Jr., another missionary in Africa, was accused of child sexual abuse: Say nothing, and send the alleged abuser back home quietly. Like Miller, Wade’s wife, Diana, was the daughter of a multigenerational Baptist family and “loved being a missionary,” court records show. She discovered that her husband was a pedophile in June 1985, after the family returned to Alaska. She was shocked to learn that her supervisors already had known for at least three years that her husband was abusing their eldest daughter. By the time Diana Wade discovered the truth, her daughter’s life was falling apart: She was pregnant at 17 and planning marriage when she announced why her father should not perform or attend the ceremony. Diana Wade immediately called police. Tom Wade was convicted of five counts of felony sex abuse of a minor in Alaska. In 1985, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison, records show. She also filed for divorce, a step her church considered an “unpardonable sin” but that she considered necessary to protect her children, letters to her employer show. She sought compensation for counseling and medical bills to address “mental and emotional scars (that were) much more devastating than any physical effects.” To her shock, her requests were denied. And she and her estranged husband were both forced to resign, letters show. “I am deeply hurt. ... I find it difficult to accept that because of what Tom alone did ... my calling and commitment and ministry are of no account and are to be thrown away along with his,” she wrote. SEARCH OUR DATABASE: Look at Southern Baptist church officials who were convicted or pleaded guilty Diana Wade filed a lawsuit alleging that the mission board had broken contractual promises to protect her family and increased harm to her children by concealing her husband’s criminal behavior. A jury decision favored the family. But the Wades lost in 1991 after the board appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court. Mission board leaders were forced to address the allegations publicly only because of the lawsuit. Board officials never said whether they later investigated if other children were abused by Wade, a missionary in Kenya and Botswana from 1976-84. In all five cases the Chronicle investigated, it was unclear if missionaries who’d been accused of — or admitted to — abusing missionary children were investigated to see if they abused local children.

Trouble in Taiwan Allegations of cover-ups involving child abuse weren’t confined to the missionary hierarchy in Africa. In 1984, 15-year-old Harriet Sugg told a pastor at her Taiwan boarding school that a missionary molested her. The pastor called the principal, who called her parents, both missionaries, to the school. She was sitting in the headmaster’s office when she first told them what happened, said Sugg, who contacted reporters after reading the Chronicle investigation, “Abuse of Faith.” The man she accused, Walter Dildy, was friends with Sugg’s parents and worked as the school’s maintenance director. She called him “Uncle Walter.” When Sugg was 9, she said Dildy called her over from the playground and took her upstairs to a bedroom in another family’s house.

“He said, ‘I’m going to show you what we’d do if we were both grown-ups,’ ” Sugg said. After Sugg complained, Dildy was sent back to the United States and resettled in Texas. She thought he would be treated and get better. “The good thing is, my mission leaders believed me,” said Sugg, now a 50-year-old teacher in Florida. “From the distance of years, I see the action wasn’t enough.” The mission board released no information to the public about Dildy, who died recently. Board archives show he and his ex-wife were based in Taiwan from 1977-86. Dildy wound up in Houston, where he worked as a pastor at First Baptist Church Recreation Acres. In 1994, Dildy accepted a plea deal for deferred adjudication on a charge of misappropriating approximately $16,000 in church funds. His second wife and widow, Kay, told the Chronicle she had heard child abuse allegations about her husband but called them “lies” invented by his ex-wife, a former missionary who has since died.

The board responds The mission board was forced to make public statements about abuse allegations involving a different former missionary in 2002 — three decades after William McElrath, a longtime Indonesia missionary, first privately told employers that he had abused colleagues’ children, McElrath’s own letters show. Linda Davarth, 55, had lived in Indonesia since she was 8 with her brother and missionary parents at the same time as McElrath. Known as “Mac,” he was a gifted writer who played the banjo. He always seemed to have a child on his lap. When Davrath was 9, in 1972, McElrath sat her on his lap at a playground and fondled her.

It took until she was 14 for her to tell her parents. Her father, she said, immediately reported what happened to a mission board official in Indonesia. Nothing happened. “All the adults knew about it, and no one did anything,” Davarth said. By the time Davarth reported McElrath in 1977, mission board leaders had already heard similar accusations, letters and other records show. In 1973, he confessed to molesting another child and a note was placed in his file, but mission leaders let him continue to serve. In 1978, another incident caused the organization to restrict McElrath’s interactions with children. Still, he remained in the field, board records and correspondence provided by victims shows.

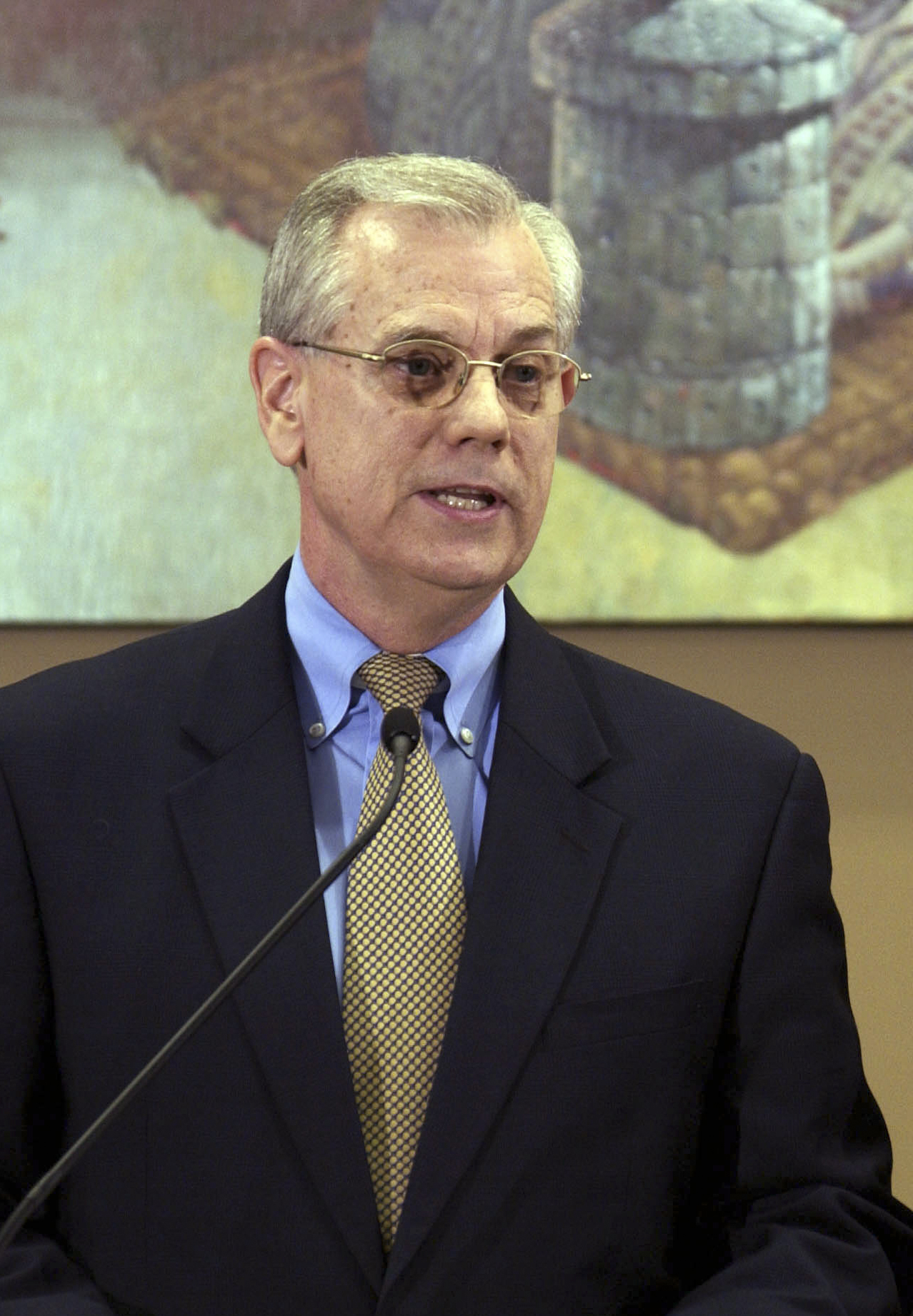

Finally, in 1995, Davarth and several others wrote Jerry Rankin, mission board president from June 1993 to July 2010, complaining about McElrath. That same year, the board fired McElrath for “immoral lifestyle unbecoming to a missionary.” McElrath separately sent letters to members of six missionary families he described as “impacted” by his actions — both parents and children. “Please forgive me for having touched you too intimately when you were a child many years ago,” he wrote in sharp cursive to Linda Davarth. “I deeply regret having abused a family-like situation.” Davarth’s brother, Eddy Ruble, later exchanged letters with Rankin.

Rankin, as a former missionary in Indonesia, had served with McElrath and admitted he’d heard ugly rumors. As board president, he advocated for keeping the incident within a small circle. “I see no constructive purpose by making a general accounting of (this) matter to all our missionaries and to Southern Baptists in general,” Rankin wrote to Ruble. After leaving Indonesia, McElrath and his wife moved to Raleigh, N.C., and joined a Southern Baptist Church in North Carolina. He regularly worked with children, taught piano lessons and helped raise his blind niece. (In his 2002 “open letter” to family and friends, McElrath said he informed that church’s senior pastor about what he had done as a missionary, but denied abusing children after 1973.) When survivors learned in 2002 that McElrath was still involved with children, they again contacted the mission board. The agenda of a June 2002 meeting notes that they wanted to publicly share their stories, create an independent advisory committee, notify law enforcement and monitor all perpetrators after termination. The IMB subsequently issued an unusual news release. “Even though wrong behavior took place nearly 30 years ago, the scars and repercussions are very real and painful," Rankin told Baptist Press. "We are firmly committed to reaching out to victims and dealing decisively with violators." Five years after the IMB promised survivors it would “publicly expose any missionary found guilty of such abuse,” the board quietly investigated another missionary, Aderholt, for sexual abuse. Internal investigators concluded that he had “more likely than not” had an “inappropriate sexual relationship” with an underage girl, Anne Marie Miller. But the information was not shared with the public or police. By then, Aderholt, who went to Hungary in 2000 as a missionary, had become the IMB's regional strategy associate in Central Europe. According to his own resume, he had visited 29 countries. Aderholt resigned before the board could meet about whether to fire him, documents show. He listed two top IMB personnel as references and became associate director and chief strategist of the South Carolina Baptist Convention. The board released information about the reason for his resignation only after Miller publicized the allegations and went to police in 2018. Aderholt’s attorney did not respond to requests for comment. Aderholt was subsequently charged in Tarrant County with sexual assault of a child under 17 and with two counts of indecency with a child by contact. The case is pending. In April 2019 — 12 years after Miller first complained — the IMB made its first appeal for information from anyone who had known Aderholt as a missionary.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.