|

Inside the mind of the paedophile priest

By Suzanne Smith

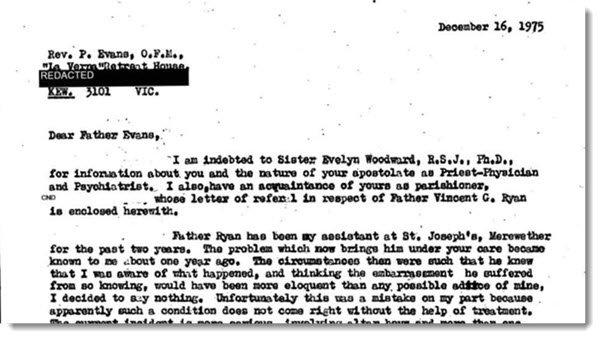

[with video] Born an only child in 1938, Ryan was raised in East Maitland on a working-class farming hamlet 40 minutes up the road from Newcastle. His father Joseph, a labourer who drifted between jobs, was a violent alcoholic who beat his submissive wife Ella with his fists. Joseph threatened suicide on a regular basis in order to control Ella. A devout Catholic, she submitted to the blows and never contemplated leaving her husband. Violence and abuse also stalked the young Vince Ryan outside the home. From the age of eight, he was sexually preyed upon by a boy four years older who lived nearby. The sexual abuse continued until Ryan was 16, and according to his psychology reports, he found some of the interactions pleasurable and didn’t view the relationship as abusive or exploitative. For a boy whose parents never showed him real affection, being sexually abused was a form of social contact. When Ryan showed any affection towards his abuser, the older boy would respond with yet more sexual violence. Ryan has never said a harsh word about his abuser. Vince Ryan has been receiving counselling, on and off, from a forensic psychologist since 2010. Dr Gerard Webster has treated more than 50 paedophiles, many of them priests and Christian brothers who have spent time in prison. He says the domestic violence Vince Ryan experienced as a boy helped develop his paedophilic tendencies. “I think there is something incredibly damaging and generally disavowed by society when a child, a boy — because most offenders are boys — sees two people that they are emotionally dependent on and love, attacking one another … these young witnesses have been severely affected at the time when they are developing their roadmap for relationships. They’ve got a broken map. They’re taught that any might is right. Anything goes.” Despite the violence he witnessed at home, Vince Ryan was very close to his alcoholic father. He perceived him as a wounded man. In a subconscious way, he identified with the perpetrator in his house, Webster explained. “I think there was a culture of acceptance of things that were really unacceptable,” said Webster. “His mother was traumatised, but she accepted it as a good Catholic woman that she had to stay in a relationship with her husband.” On his formative path towards adulthood, Ryan identified closely with two perpetrators: his father and his abuser. It would become a lethal mix. * * * Ryan found himself immersed in a world of young men studying to be priests, isolated from their families for long periods, discouraged from developing any friendships, and where celibacy was the norm. Before he entered the seminary at the age of 19, in 1958, he told a priest in confession that he had desires for young boys. The priest, however, assured him that “if he said his prayers, God would look after him”. Ryan talked about this period of his life to one of his former altar boys and now journalist David Brearley. “He had a terrible time in the seminary in Springwood,” Brearley recounted, based on a rare interview. “One day a year they would get the mini bus and go to Echo Point in the Blue Mountains and get an ice cream and there would be high spirits and fun. Following one of these trips, Ryan did some night time grappling with a young man in the next bed. The other seminarian confessed the behaviour to a priest the next day and Ryan was asked to meet with the priest, who told him he was now forbidden to have any sort of relationship with the fellow seminarian. They were 19 or 20, and Ryan told Brearley that he wondered whether he could have had a happy relationship with this man, had it been allowed. For an isolated child growing up in an abusive household, Catholicism provided Ryan with a haven. The church offered him a structure, a world that made sense, a place with a noble purpose. Students in seminaries in the ‘60s were taught that becoming a priest takes your being through an “ontological change into the divine”. Some offenders interpreted this as giving them more power and entitlement — a “messiah complex,” as canon law expert Kieran Tapsell describes it in Potiphar’s Wife: the Vatican’s secret and child sexual abuse. Others believed it was part of God’s mission to make them better servants of the people. The big problem with the so-called “ontological difference” between priests and laypersons, argues Bishop Geoffrey Robinson, a senior Catholic bishop who has pushed for reform in the church, is that it enthusiastically embraces “the mystique of a superior priesthood”. “Whenever I see young priests doing this,” he wrote, “I feel a sense of despair, and I wonder whether we have learned anything at all from the revelations of abuse.” After four years at the Springwood seminary, then one term at the Manly seminary, Ryan travelled to Rome in 1962 to complete a theology degree. He remained there until 1966, studying alongside other prominent figures including Cardinal George Pell. Because the church considered Ryan to be an intellectual, he was enrolled in a doctorate of canon law. Ryan was highly intelligent and loved Italian culture, art and music. He arrived in Rome as the Vatican was undergoing a reformation resulting from the adoption of Vatican 2 as a type of “glasnost” for the church. Vince Ryan was excited by this transformation. More importantly, he formed some good, wholesome bonds with friends outside the church. It must have been a relief to be free of his past. In 1972, Ryan was recalled from Rome. After a short stint at a parish in Singleton in north-western NSW, he was sent back to Maitland to become an assistant parish priest. As soon as he got there his mood soured and he started molesting boys. “He said he was suicidal as a child and now suicidal as an adult again,” said David Brearley. “The only relief was when he was actually together with a young student and it would disappear as soon as the child was gone.” He told Brearley he would go into a deep funk if the child didn’t turn up for the day. “He said he couldn’t relate to adults like he could to children.” He had left the liberal excitement of Italy to arrive at what he saw as a moribund church, staffed by old men who just didn’t like him. Once again, he felt extremely lonely and, in his 30s, found himself transported back to the rigid world of his childhood, except now there were plenty of altar boys in his charge. “I never had to threaten anyone not to talk, I never did that,” Ryan told Brearley. “I thought I was in a loving relationship, I know that’s stupid but that is where I was.” But how could Ryan possibly characterise his interactions with boys as a “loving relationship”? “The word ‘love’ is not supposed to be used,” he told Brearley, “but … this connection between you and your victim is the thing that is stopping you from committing suicide, who is giving you some life, some humanity, some human touch and not just the sexual stuff …”. In his mind, he formed relationships with these boys; he felt he loved them and he viewed himself as their caregiver. But he was also their predator. As one victim described in his police statement, Ryan had a Jekyll and Hyde personality. Before abusing the boys, Ryan would remove his glasses. The altar boys came to dread this simple action, a signal that another attack was imminent. For the victims, it marked the moment Ryan went from caregiver to monster. Like all paedophile priests at that time, Ryan had papal protection. That’s because, in 1974, Pope Paul VI issued a document known as “The Pontifical Secret” or “The Secret of the Holy Office”, which meant any allegation or investigation of sexual abuse against a cleric was kept secret. Any bishop who defied this decree and reported the abuse to civil authorities or police could be ex-communicated. As revealed in the recent Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse, a pervasive culture existed in the church that saw these crimes as moral failings, rather than criminal ones, supported by an assumption that priests could be treated and cured. This culture of secrecy, according to Dr Gerard Webster, created a “potent” setting for this maladjusted behaviour to flourish. * * * By 1975, the church knew Ryan had significant problems. He had cried as he informed his immediate superior, Monsignor Patrick Cotter, of his attraction to young boys, according to documents tendered to the royal commission. He was packed off to a retreat facility in Kew, in suburban Melbourne, known as the La Verna Retreat Centre. As Cotter wrote to the treating doctor, Dr Peter Evans, at the time: “Father Ryan has been my assistant at St Joseph’s Merewether for the past two years. The problem which now brings him under your care became known to me about one year ago. The circumstances that were such that he knew that I was aware of what happened and thinking the embarrassment he suffered from knowing — so knowing would have been more eloquent than any possible advice of mine, I decided to say nothing. Unfortunately, this was a mistake on my part, because apparently such a condition does not come right without the help of treatment. The current incident is more serious, involving altar boys and more than one.” Parishioners were told he was going to Melbourne for a “pastoral” course of study, and that’s exactly what he did. But according to testimony by the consulting psychiatrist before the royal commission, Dr Peter Evans, a Franciscan priest, Ryan only had an initial assessment and did not receive any treatment. During the assessment, Ryan disclosed to Evans that he had had “sexual contact with adolescent boys and that this was known to Cotter [and] Sister Woodward”. After this consultation, Evans told Ryan that treatment would be more successful if it were done in Ryan’s own home environment. This doctor soon left the facility and Ryan fell through the cracks. He spent a year enjoying the delights of Melbourne, going to the races, satisfying his urbane tastes and enjoying his classes. “The church’s sense was that he was a sinner who had a weakness,” said Webster, “who had to pray and he would somehow be redeemed and therefore he could come back into the ministry without sexually abusing children … magic!” At the time he was sent to Melbourne, Ryan was under the supervision of Sister Evelyn Woodward, a nun and a psychologist who assessed priests for their suitability for ministry. Woodward confirmed in testimony to the royal commission that she eventually knew Ryan hadn’t received any treatment, apart from one initial assessment. Evans told the royal commission: “I told Evelyn Woodward I would do an assessment diagnosis as I would be leaving [the centre], not treatment … I repeat [I told her] La Verna was not a treatment centre.” Looking nervous and agitated, she was cross-examined as to why she hadn’t reported Ryan to the police. She blamed her lack of authority as a woman in the church. Senior Counsel: “Just coming back to the question that his Honour was asking you about involving the police, you suggested in your statement that you simply didn’t think of going to the police at all back in 1975; is that right?” Sister Evelyn Woodward: “Never.” SC: “Was that just because you saw your role as being to report the matter up the chain and once that had occurred, you were leaving it to others to deal with?” EW: “Yes and no. I think another factor was the position of women in the church at the time. We were pretty low in the pecking order and there was a hierarchical system which I think led me to say ‘I’ve got to hand it over to whoever’s in charge of the Diocese’ if that makes sense.” Following and obeying canon law “served to rationalise and deepen the culture of secrecy,” said Kieran Tapsell. “When you have bishops who have taken an oath to follow canon law, being threatened with excommunication if they go to the civil authorities, it is pretty obvious what they are going to do.” * * * Vince Ryan returned to the Maitland-Newcastle diocese in 1976. His superior, Cotter, immediately put him in charge of training the altar boys at Hamilton, in the suburbs of Newcastle. Over the next two decades he sexually assaulted another 27 children with impunity. At Hamilton, in the presbytery where he and Cotter lived, Ryan would take young boys up to his bedroom and abuse them. Cotter would tell the housekeeper to go upstairs and knock on Ryan’s bedroom door and tell the boys it was time to go home. Ryan himself believed he needed treatment for his paedophilia. He told Webster, years later during counselling, that while he still loves his church, he is angry that he was moved from parish to parish and didn’t get the treatment he needed after disclosing his problem. On more than three occasions, Ryan told various church officials, including his immediate superior, that he was a paedophile. He confessed it to his priest in Maitland before entering the seminary. He admitted it to his superior, Cotter, in 1975 before being sent to Melbourne. And he told the psychologist, and priest, Dr Peter Evans at the La Verna Retreat Centre in Melbourne. Does Ryan ever think about what he did to those boys? The Australian journalist, David Brearly, who is writing a book about Ryan, says he sensed from his interview that the priest doesn’t dwell much on his interactions with the boys. “I think his contrition is real but maybe not as intense as it might be,” said Brearley. “He was talkative, but it wasn’t until I transcribed the interview did I realise how much he could control an agenda. So there is about nine pages of transcript, probably one fifth is complaining about the Newcastle Herald — how can you complain about the Newcastle Herald? — and another fifth is complaining about jail and its failure to rehabilitate people.” But one of Ryan’s answers stunned David Brearley. Asked about the royal commission, the priest told him: “As far as I am concerned this is a conspiracy between newspapers and politicians, they need each other. The royal commission, I think it should have been about why in our country there was such a disaster of child sex abuse … to go straight to institutions, I don’t get the reason, I don’t get it … the vast number of child sex victims are in the home.” Ryan also blamed the parents of his victims for not going to the police back in 1975. “It’s a hard concept to swallow,” said Brearley. “He thinks he was one of the boys. I think Ryan has achieved a mighty effort of self-deception, when you think he was a 30 to 35-year-old and he was abusing 10-year-old boys and he can’t see the difference.” Ryan’s rapacious appetite for young altar boys was only curtailed when Gerard McDonald and Scott Hallett walked into the Newcastle Police station in 1995. They spilled the beans to constable Troy Grant, a junior police officer who was until recently the NSW police minister and for a time NSW deputy premier. He was the first police officer to investigate a priest in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese, and the first with a successful prosecution. Since 1995, he has kept in touch with all of the victims who came to him about Ryan. After Gerard McDonald and Scott Hallett came forward, many more followed. One case, in particular, has caused Troy Grant great trauma and sadness. In October 1995, a man contacted Grant at the Newcastle police station to report abuse that lasted five years while Ryan was the parish priest in an outlying parish. Ryan had committed more than 200 acts of abuse against the boy while he was between the ages of 12 and 17. The boy had no father, but Ryan saw himself as his caregiver, his de-facto dad. In 1992, the boy was in a terrible accident and ended up in hospital, fighting for his life. When Ryan heard the news he raced to the hospital. Distraught at what he saw, Ryan climbed into the boy’s hospital bed and hugged him while crying uncontrollably. When the nursing staff called the diocese to have the priest removed, a Catholic chaplain was despatched to remove him. But no one informed child protection authorities; after all, Ryan was a priest. The boy was hospitalised for four months, but recovered. Ryan was later convicted for the crimes he perpetrated against the boy. This victim died in 2018. The coroner has yet to release the findings on the cause of death. * * * It was only after 13 years behind bars that Vince Ryan was given his first intensive treatment for paedophilia inside the jail. Finally, he told his psychologist he understood the suffering he had caused to his victims. Ryan participated in a program known as Custody Based Intensive Treatment (CUBIT), an evidence-based treatment program for moderate to high-risk sex offenders, which takes 12 months to complete. Inmates are encouraged to identify and reflect on their unique risk factors (the things that make them more likely to reoffend) and to develop skills to reduce those risks where possible. The intensive therapy also helps inmates to initiate behaviour when they enter settings where they might offend, known in psychology jargon as “protective factors”. The offenders also develop what’s called a “relapse prevention plan” that helps them maintain “a commitment to a non-offending lifestyle”. A recent research study found the programs have halved the rates of re-offending. Ryan wishes he had been given access to this therapy many years earlier, according to Webster. “These programs are very effective,” said Webster. “The group work with other prisoners has been very important. The only negative is the CUBIT program can’t get to the causes of paedophilia in inmates, but it does a really good job of treating the symptoms.” Ryan apparently believes it has given him some of the answers to his own questions as to how he could have perpetrated such horrendous abuse on children. In a statement to INQ, the Maitland-Newcastle diocese confirmed that it supports Ryan’s on-going counselling, with Dr Webster. Webster says the clerics he has counselled are different to non-religious offenders. “At the beginning of treatment there tends to be a lot of minimisation of their responsibility, externalisation of their responsibility. They often blame the children or see the children played a part in their offending and therefore feel somewhat unjustly accused of doing the wrong thing when they saw it as a collaborative thing that the child benefited from,” he said. “I find also a strong theme with priests who have often previously gone into the priesthood or into a religious order to meet their previously unmet emotional needs, like a need for safety or a need for agency for a sense of ability to be powerful and do good things.” Another common factor among these offenders, says Webster, is that many clerics, like Ryan, suffered abuse as children. In April, Vince Ryan was convicted for abusing two more victims. He looked passively as Judge Dina Yehia read her judgment. Her words cut the air like a knife: “He held a position of high moral authority and influence in the community … the children he interacted with were betrayed in a profound and egregious matter … these acts must be punished…” She told the court he had been assessed as low risk, had been in counselling for a number of years and had been rehabilitated. Then sentenced him to another three years and three months in prison. He was led away in handcuffs before heading to Long Bay Jail, where he will be given the status of a pariah, a child sex offender, the lowest of the low. His psychologist argued he could be assaulted in jail and may not survive. He is 81 and already frail. He must survive for 18 months before he can apply for parole. After the court case, Gerard McDonald emerged from the Downing Street Centre and punched the air with his fist. “Yes!” he shouted to the waiting media throng. “He gets a couple more years, we have got life … the judge says he is reformed.What a load of bullshit.” Ryan, meanwhile, is still a priest, although his faculties have been removed and the Maitland-Newcastle diocese awaits further instruction from the Vatican, meaning he can’t say mass or call himself “Father”. The current Bishop of Maitland- Newcastle Bill Wright has issued an unreserved apology for the Church’s involvement in the Ryan case. The bishop in charge at the time explained that Ryan was retained within the priesthood so the church could better keep an eye on him. An ironic statement, perhaps, given it was his beloved church that helped foment the environment that covered up the sexual crimes Vincent Gerard Ryan inflicted upon 37 children. If this story has raised concerns for you, you can seek assistance via Lifeline on 13 11 14, and Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.