|

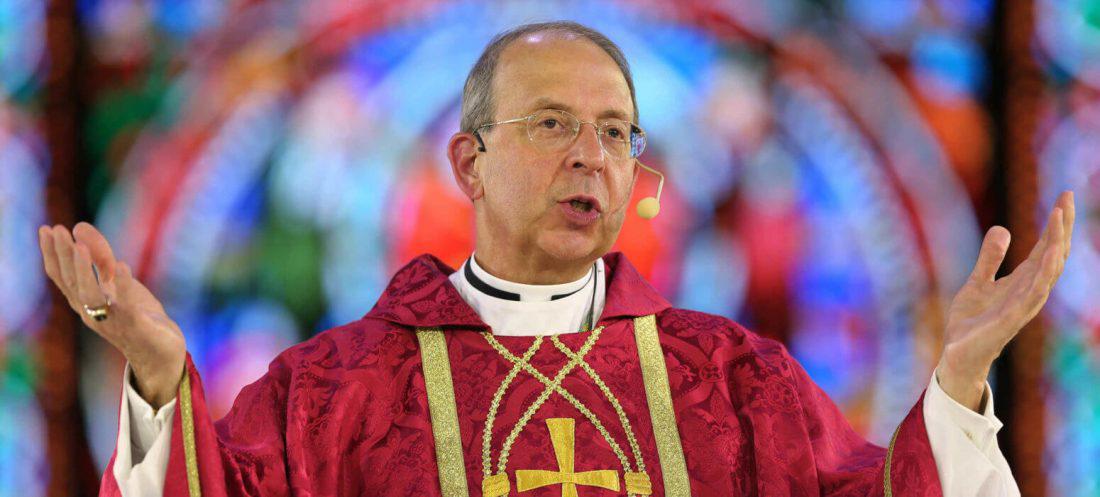

Sunday Sit-Down With William Lori, Archbishop of Baltimore and Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston

The Intelligencer

[with video] But there are other things that every bishop has to worry about, and one of them is sustaining Catholic schools when the enrollment goes down. Administering a hospital in this day and age is a very challenging business for anyone; while there is a lawsuit underway, I might mention that we have new management at the hospital, I might also mention that it’s a really great hospital. It didn’t get that way (by accident); it’s really a good hospital because there’s been a lot of care and attention given to it, and it’s a major employer there in Wheeling. So the bishop, like every bishop, he had to face some challenges, like every bishop he did some very good things in the diocese but unfortunately I think the things that showed energy and vision have been in some sense really undermined by issues of personal behavior. That’s most regrettable. – The legacy Michael Bransfield leaves behind — the spending, the sexual harassment allegations, let’s focus on those in particular because those issues are what prompted you now to oversee the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston as its apostolic administrator — what was the damage done to the Diocese and the faithful in West Virginia by these actions? Archbishop Lori: Let me first speak to the harassment allegations. I think of the very direct effect that has on the people who are the objects of that kind of behavior. I think that when I learned of this firsthand it really broke my heart. It really does a lot of damage to people in a deep and personal way. And as a bishop, as one who loves my own priests and seminarians, you just never want to see that happen. – To be clear, this was sexual harassment of young priests, correct? Archbishop Lori: Sexual harassment of younger priests and some seminarians. My heart broke for them, it was deeply disturbing. One of the things that has to happen there is a healing not only for these individuals, but for the whole presbyterate because when some of our number are affected, all of us are affected. Secondly, the reports of excessive spending in a state that has many economic challenges and social challenges are deeply disturbing. I think that it’s so understandable that people living in all parts of West Virginia would be disturbed by this. I worry, whether it’s sexual harassment or whether it’s the overspending, is the effect that it has on people’s lives of faith. It’s not the bishop who controls the church, he is but the Lord’s instrument. It’s not the priests, we are the Lord’s instruments, we are as St. Paul says, “Earthen Vessels.” Nonetheless, when any one of us departs from standards of conduct that are appropriate to our way of life and to our responsibilities, it can undermine the faith and goodwill of people. As a bishop, as a shepherd, I worry about that. What breaks my heart is I can’t be there enough to be the one to really help restore this, but that’s the work that has to be done. – Explain how, in your opinion, the healing of the church begins in West Virginia? Archbishop Lori: I think the healing has begun in some sense. It’s hard to see when you take the first steps, it’s hard to know what the ultimate outcome will be, but by doing things like putting out the names of priests who have offended, by putting in a third-party reporting system, by doubling the size of the finance council and bringing in people with additional expertise and meeting with them monthly, by also doubling the size of the review board for sexual misconduct, having them meet more often, by putting back into place some of the policies and procedures that had been overridden … those are not glamorous steps, and most people don’t pay a lot of attention to them. But those are steps toward healing — they’re sort of like doing the ground work. When you’re going to build a building, you’ve got to do site work. I’m sort of doing site work, I don’t expect a bit of credit for it any more than the contractor does who comes and removes the rocks so you can build a beautiful building. I see my responsibility working with really good people … to begin to do the groundwork, so that when the new bishop comes in, he can be a shepherd who, as the Pope says, has the smell of the sheep, loves people. Part of it is just going out and being present, just being there. Visiting parishes, getting to know people, listening to people, hearing their stories, taking them to heart. We bishops are not magicians, we are not dictators, we are shepherds. What we need to do is gather and attract to ourselves good co-workers, a good team. That includes clergy, of course, but it also includes good lay workers. … Healing has got to be led by the shepherd, the bishop, but for it to really take effect, it involves everybody in the local church, and I’m praying you’re going to get exactly that type of bishop. – Since you’ve been in your role in West Virginia — about 10 months now — you’ve overseen two major initiatives: the public release of priests credibly accused of sexual abuse of children, and also, under order from Pope Francis, the investigation into Bishop Bransfield. Let’s talk about the priest list — why did you authorize the list to be compiled, and then, once it was finished, release it to the public? Archbishop Lori: I think, in my own history in this very sad aspect of the church’s life, I’ve always felt it was important to get the names out there. When I was in the Diocese of Bridgeport, I did it. When I came to Baltimore I found we were the second diocese in the United States to have done it, we did it in 2003, I believe. You do that because as someone says ‘gosh, I was harmed by this priest or that, but maybe I’m the only one.’ When they see the name on the list they get the courage often to come forward, and when they come forward what we can provide for them is the help and counseling they need to be able to heal, and the pastoral help. One of the things I’m doing is selling the former bishop’s residence and taking the money from those proceeds so that there will be funds to provide pastoral assistance for those who have been harmed. I think that’s why it’s important to do. And we do it here in Baltimore, we’re a much more complex place ecclesiastically, so we’ve made sure to update our list through the years including with the recent revelations from Pennsylvania. We asked ourselves who on that list served in Baltimore; we found some names and put them on our website. Not only the names but also the information about where they served, when they served so that anyone looking at it can say if that happened to me I can ensure to make a report. – Is there a process in place now in West Virginia so that as additional names of priests credibly accused of sexual abuse are discovered, they will be added to the list and made public? Archbishop Lori: So, a couple things: one is there’s got to be an easy way to make a report, and so putting in the third party reporting system such as we have in Baltimore … I think is an important step. People might hesitate to tell their parish priest, they might hesitate to call the Chancery office, but if it’s a third party reporting system it gets a little bit easier. And we take every call on that line with the utmost seriousness. The second thing is to ensure people who do come forward that they’re not only going to get a good hearing, but also a compassionate hearing, and that this isn’t just being handled by the Chancery staff. So, what we’ve done is to have strengthened the independent lay review board, that we review every decision and every case that comes forward. So what we’re trying to do is create confidence that if you make a report, it’ll be taken seriously. The other thing that the diocese has done for many years is to create a safe environment, and so the training, the background checks … a lot of people will say, ‘I never did this, why do I have to be background checked in order to let’s say teach in a Catholic school?’ The answer is we’re creating a culture in which sexual abuse and harm to the vulnerable isn’t tolerated. … The other thing I’ll mention that should be of some comfort is complete cooperation on these matters with the civil authorities. For example, we would never investigate these matters until we get the green light — they do their investigation first. Our investigation is not about whether a crime is committed; our investigation is about suitability for ministry and what ought to happen to the alleged perpetrator. But we fully cooperate with the civil authorities. What we want the church to be is a safe place. It’s been a long time since we’ve had a fresh new allegation against one of the priests of Wheeling-Charleston. Do we think it’s working, do we think we’re doing it perfectly? By no means. Anyone who’s ever dealt with this in any sector will know that this is a work in progress, you work at and you try to get better and better at it. Nobody claims perfection here. – The report initially centered on allegations of sexual harassment. In the end, the report you authorized to be sent to the Vatican found those allegations to be credible. You knew Michael Bransfield, you’d been his guest in Wheeling. You mentioned earlier you were sickened when you found out the details. Can you go further into your thoughts there? Archbishop Lori: I was really saddened. I’ve known the bishop for a long time, but you know him on a friendly basis, you don’t know these details. Certainly the harassment was new, the extent of his spending … all that was sad news to receive. But I’ll tell you what I felt I had to do; I felt when I had first-hand information, actual information, the thing I had to do was immediately report it, which I did to my ecclesiastical superiors; and did so within the same day as receiving those allegations. And in very short order that information was received by my superiors in Rome and shortly thereafter they appointed me to do the investigation. So that was in August (2018). I was authorized in September by the Holy See to do the investigation. As a metropolitan archbishop I don’t possess the authority to investigate on my own, I have to be authorized by the Holy See, but once I was I said you know there’s different ways I could do this. I could ask other bishops to do it with me and for me, I could do it myself, but I said I don’t have of myself the expertise I need to do a thorough job of this, and that’s when I went to the five lay investigators including a former state’s attorney, including a forensic accountant, including a specialist in HR, and since it’s a church investigation a church law expert. And I said to them, ‘no holds barred.’ Where does the truth lead? Tell us and bring back this report. And they spent five months doing it, they interviewed 40 people if I’m not mistaken. As part of the process they interviewed bishop Bransfield, because if you’re doing an investigation you have to hear all sides. They compiled a very thorough report and submitted it to me in February of this present year. The purpose of the report was not to report on all things wrong with the church; there’s plenty to talk about there, let’s be clear. The purpose of this, it was a report authorized by the Holy See, I was charged to develop it and complete it and to give it back to the Holy See. It’s theirs for the purpose of reaching decisions regarding the future of bishop Bransfield. So that was the purpose of it, it was a fairly circumscribed purpose but the report was complete and hard-hitting; it pulled no punches. – The report found that concerns of sexual harassment of young priests also had been raised during Bransfield’s time in Philadelphia, and in Washington, D.C. Obviously some church leaders knew of the issue, were aware that these concerns had been raised, yet he was assigned in 2005 to oversee the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston. Why did no one question his appointment? Archbishop Lori: I’m not really sure. The church has a long history, 2,000 years. And a lot of bishops have been appointed over 2,000 years and it would have to be said some appointments were better than others, some should never have happened and God bless us all, sometimes great saints get appointed as bishops and thank God that happens. I don’t know, I wasn’t privy to that, I was a bishop in Bridgeport at the time. There might have been people who knew all kinds of things, I truly wasn’t one of them. I knew Michael on a friendly basis, we worked together on boards and things of that nature and I regarded him as a friend but I didn’t regard myself as his closest friend by any means. … What comes out of this for me? I think that it lays forth a challenge to the process of appointing bishops. Who is asked, how many people are asked, what state of life they are in, by that I mean are they priests, other bishops, are we asking lay people who are in a position to know. We are not looking for heresy; we’re looking for direct information. In other words, do we put those appointments through a sufficient number of filters. While on the face of it it generally works pretty well because I know a lot of bishops, none of us are perfect, but I know a lot of bishops giving it the old college try, I among them. I think that this is an object lesson for us to go back and say are we doing everything we should. – What do you say to the young priests in the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston who believe they were sexually harassed by Bransfield — who at the time was their bishop? Archbishop Lori: First of all when they came forward the first time the most important thing I did — and I take no credit for this, sometimes the Holy Spirit just kicks you in the pants and the Spirit did that to me that day — you just listen. You take it seriously. I’ve had it happen to me, I’ve gone to people and asked them to hear me out, and I know how much I appreciate it when they do. But someone just willing to take you on your own terms, believe you even though it was a colleague of mine. I listened thoroughly to what they had to say, I listened actively, gave them as much time as they needed to tell their story and then … there was an immediate follow-up. I said ‘OK, I believe you and I take you seriously.’ The other thing has been my ongoing contacts, periodic calls, when I’m in town visiting just saying ‘how are you doing,’ providing also the kind of help that might be necessary because if you’ve had this happen to you, it’s not just a matter of telling one person one time, you do have to deal with the longer-term effects of that in your life; I think we’re trying to do that but it’s going to take time. – Three priests who were close aides to bishop Bransfield — Kevin Quirk, Anthony Cincinnati and Frederick Annie — you reassigned them from their administrative duties and back into pastoral roles. Why were they reassigned? The report called for that, what prompted you to move forward? Archbishop Lori: First of all I did make the reassignments. … I just felt it was the right thing to do for everybody concerned; for the three priests themselves, for the good of the diocese and for the good of the healing process. It seemed to me these difficult decisions were the right things to do. I probably would have assumed that the new bishop would have been doing these things … because most of us apostolic administrators are caretakers, but it seemed to be the right thing to do and that’s why I did it. – Did you believe that once the report came out that you needed to make the reassignments, as these three priests were named? Archbishop Lori: It seemed to me the right thing to do at that time. Did it push up the timetable? Yes. Would it have been done anyway? Yes. – Let’s move on to the spending aspects of the report. Michael Bransfield spent, according to the report, $2.4 million in diocesan funds for his own travel, more than $4.5 million on his home, money on jewelry, alcohol. Sitting here now, when it comes to the spending, what shocked you the most with the investigation’s findings? Archbishop Lori: No one particular aspect of the spending bowled me over, it was the composite picture because of the stark contrast between the spending habits that emerged and the pastoral and social needs of the place he was serving. Even if you’re serving in a wealthy area, there’s no excuse for any bishop anywhere to spend huge sums of money on himself. … Pope Francis has called us to a very different reality and rightly so, but the contrast with the poverty you see in the coal country, and some of the isolated communities, or the unemployment or the opioid crisis in the state of West Virginia — those resources needed to go there. And so what this is is like a huge wake-up call saying priorities have got to change. I’d like to think here in Baltimore, I have a poor city here, and we have a beautiful Basilica and we have a big cathedral and we have schools and things and I like to think we are putting the … vast majority of our resources into Catholic Charities, inner-city schools, and things that serve the neediest and the most vulnerable and good, ordinary church-going Catholics and almost church-going Catholics, and former church-going Catholics in their pastoral needs. I’m not saying the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston hasn’t done a lot, it does do a lot — there’s a huge impact with what it does. But I think that the diversion of those resources from that mission is sad because the diocese can and should do more. – The report sent to the Vatican removed the names of 11 priests, including yours, who received $350,000 in financial gifts from Bransfield — gifts that were paid for with Diocesan funds. You’ve addressed this previously, but for the record, why did you choose to withhold the names of those who received gifts from Bransfield and only address the issue publicly after the report was leaked, and the names of those priests were made public? Archbishop Lori: First of all, I did address this and I have said in hindsight this is a decision I would do over. I’ve apologized, I’ve returned the money and I hope we can move on from there. But that said, the report comes, the initial draft, and what we’re looking at is compiling a report that is aimed at one thing and one thing only — which is to help the Holy See make a good decision, a fair decision with regard to bishop Bransfield. And so the report as initially drafted only listed that the bishops who have received gifts, not other people including priests and lay people, and we ask ourselves, is this the right thing because some of those gifts that were given were legitimate — they were for travel, they were to support good works of the church and other places, which every diocese does, and some of them were honoraria, others were gifts given in friendship, but there was no explanation. It looked like all these gifts were improper. And so barring adding pages and pages to the report, we said we’ll deal with it generically. So it does say that cardinals and prominent bishops and other folks received gifts and we give the magnitude of the gifts that were given in the report, we just don’t have the detail in there. Hindsight, I’d do it over. It was not an attempt to obfuscate or to protect. – Are gifts such as this — from one priest to another — common in the church? Archbishop Lori: It happens now and again I would say. … But to your earlier point, we also were unaware of the sources of these funds (from Bransfield). That having been said, it’s fairly uncommon. I get gifts from bishops and priests, mostly I get poinsettias and Easter lilies which I put it on the altar, and the other thing I most commonly get are books on Franklin Roosevelt, because everybody knows that’s my hobby and every time a new book comes out I usually get two or three copies of the same book. Look. We’re friends, we’re colleagues, we like each other, and so gifts of some sort are common enough among us. But never, even with the things I got from Michael, I never sensed a quid quo pro, I never imagined he did that to get something out of me, nor did he ask me for anything. – The process of ‘grossing-up’ — which Bransfield used to reimburse himself for gifts he gave to other priests — is that something you’ve seen before in the church? Archbishop Lori: Not that I know of. – As you started your investigation, and knowing you had received some financial gifts from bishop Bransfield, did you ever believe you had a conflict of interest? Archbishop Lori: No, I didn’t. … The reason I didn’t think it was a conflict was two-fold: A, I didn’t even avert to it, that’s not on my radar screen, I truly have to tell you that. No. 2, I could never remember him asking an untoward favor of me over the years. Had he asked me to cover for him or had he said if you do this for me, I’ll give you that, A, if I was a self-respecting bishop, if I did that, I would have resigned. But there was nothing like that. So I did not see then and I do not see now a conflict of interest. As you can see, it didn’t prevent me from authorizing a no-holds-barred report. – Is Michael Bransfield still on the payroll of the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston? Archbishop Lori: There’s a pension plan, it’s like any other pension plan. – In the Wheeling area, there were two schools that were closed, and there was strong pushback against the bishop. Given the excessive spending, what do you say to those who were directly impacted? Archbishop Lori: First of all, again, untoward spending, no excuse. Put more resources toward the diocese? Yes, in every case. But I’ve also been in the very difficult position of having to close schools and I know firsthand that anytime it has to happen alumni, current students, parents are upset. But sometimes, because of demographics, because of population shifts, because of the cost of tuition, a whole variety of factors, and through no one’s fault, a school becomes simply non-sustainable. No bishop wants to close a school. I’m much happier putting shovels in the ground and opening schools than closing them. But sometimes it becomes absolutely necessary. I would also say that as much money as the bishop spent on himself … the diocese spent much, much more money to sustain its Catholic schools. In fact, the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston subsidizes its Catholic schools at a level that amazes me. I couldn’t possibly do it here. There’s the resources to do it, and they do it. There are some very small schools kept in operation that amaze me, but they’re in very remote places, there are no alternatives and so the diocese does it. But, as St. Ignatius of Loyola said, the motto should be magis, which is the Latin word for more. The more a diocese can do to serve its people, the more resources you put toward the apostolate, the better. – You mentioned that the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston is a wealthy diocese, holding oil reserves in Texas. As part of this investigation, what recommendations or processes have you put in place to make sure there is more accountability for spending in the future? Archbishop Lori: I think you might remember Bishop (Bernard) Schmitt, I knew Bishop Schmitt when I was much younger than I am now, loved Bishop Schmitt. He was a native of the state and everybody loved him. He was a wise fellow, very low-key. One of the things I found was that Bishop Schmitt had some pretty good policies in place. They were a little dated … but pretty good. So I said we have a baseline here, let’s go back and ask ourselves what those were, let’s review them. Let’s ask where we went off the track, let’s ask how long we’ve been off the track and then let us ask what do we need to do to strengthen his policies so that this form of malfeasance will never happen again. And so we’re in the middle of it, it’s a work in progress. In fact I’ll be meeting with the finance council later this month for that express purpose. … My job again, to go back to my earlier analogy, I’m doing the site work. I’m removing the rocks and the boulders and looking for the PCBs in the soil, trying to get that out so the new bishop can hit the ground running. – Will you authorize the release of the unredacted version of the report? Archbishop Lori: Going back to what I said: the Holy See owns it, I don’t. That said, when it was finished and I sent it to the Holy See, I did jaw-bone a little bit with the Holy See and said, ‘I’d like to tell the good people of West Virginia as much as I can about this.’ So I said what I could and they were pretty good, they gave me some leeway. Certainly after a decision has been reached with regard to the bishop there is information in that report, some of it should not come out because innocent people would be harmed. We can’t do that. But on the other hand there is information that in my personal opinion should come out because that level of transparency will help the healing process. – You’ve been at two parishes in West Virginia since the report came out, one in Weirton and one in Martinsburg. What was your message to the faithful? Archbishop Lori: It was first and foremost the message of the Gospel. When you go to say Mass and preach, you preach the Gospel first and foremost. Secondly, it was one of solidarity with the people, good Catholics and other people in West Virginia of goodwill who are going through a difficult time. Thirdly, it was an admission, a very forthright admission of my own error in judgment, but most of all it was words of encouragement because before the spring comes you have to go through the storms, and I simply wanted to be with people, stand in the back of the church, let them know I was accompanying them as the Pope likes to say, and give them a word of encouragement that there will indeed be a new and better day and we’re working for that right now in God’s grace.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.