|

He Says a Priest Abused Him. 50 Years Later, He Can Now Sue.

By Rick Rojas

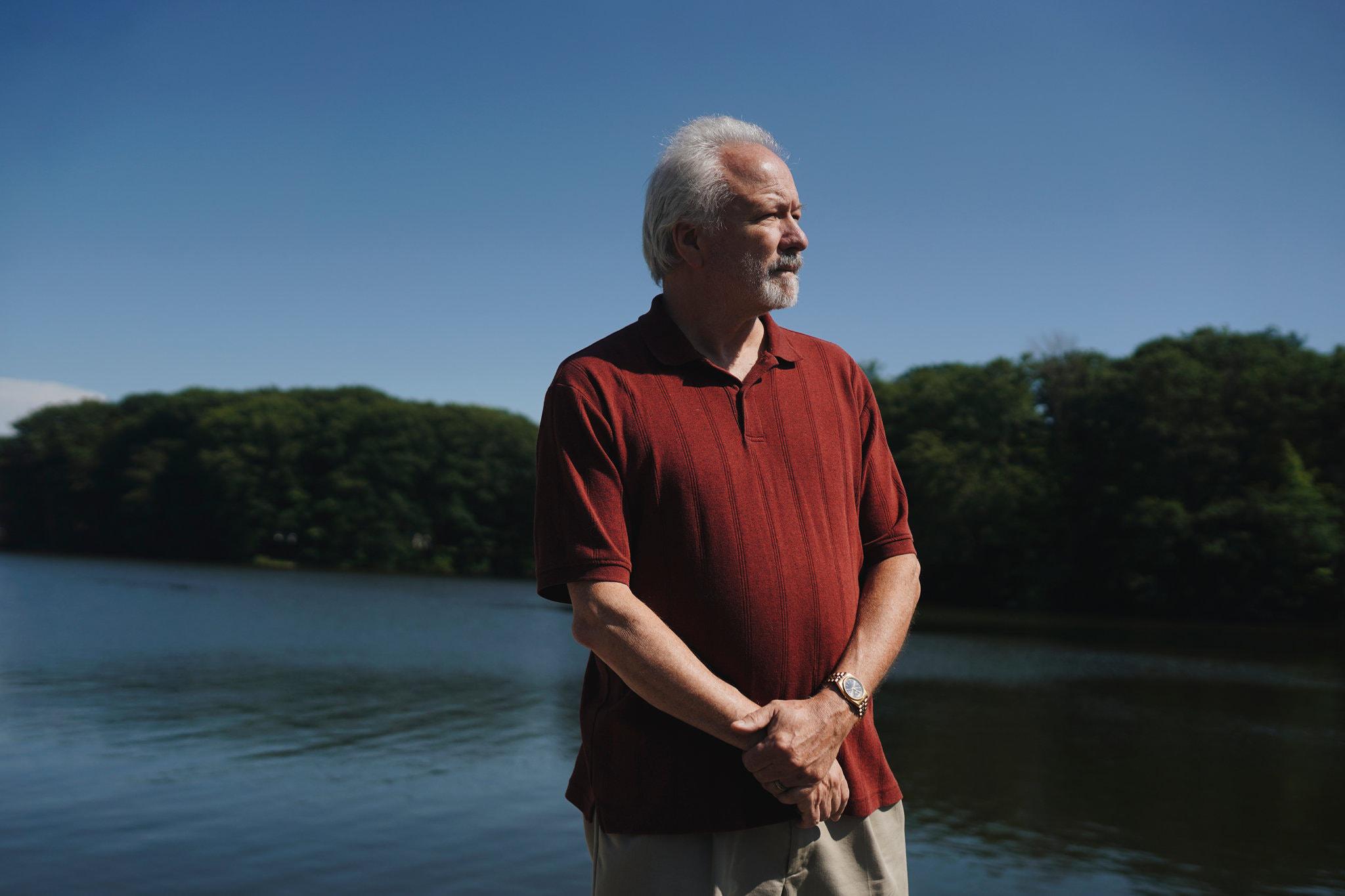

A new law has created a “look-back window,” during which claims that had passed the statute of limitations can be revived. Major institutions across New York State, from the Catholic Church to the Boy Scouts of America to elite private schools, are bracing for a deluge of lawsuits now that adults who said they were sexually abused as children will be entitled to pursue formal legal action. New York joined more than a dozen states this year in significantly extending statutes of limitations for filing lawsuits over sexual abuse. Previously, the state had required that such suits be filed before a victim’s 23rd birthday. Under the new law in New York, the Child Victims Act, which was approved by the Legislature in January, accusers will be able to sue until they are 55. The new law includes a one-year period, known as a look-back window, that revives cases that had expired, in many instances decades ago, under previous statutes of limitations. The one-year period begins on Wednesday, and the impact could cause major financial stress for many institutions in New York, including the state’s eight Catholic dioceses, which have faced a series of scandals involving abuse by clergy. Already, the Catholic Archdiocese of New York, which includes Manhattan, has sued its insurance providers to make sure they will cover claims against it after the law goes into effect. The Rockefeller University Hospital, which is facing scores of cases alleging abuse by an endocrinologist, is pursuing a similar tactic. A look-back window in California, in 2003, spurred more than 1,000 lawsuits, most against the church, and was a prelude to the Diocese of San Diego filing for bankruptcy protection. Catholic officials said they have examined look-back windows in other states to try to get a grasp of what might come. The New York archdiocese said it would likely be able to weather the litigation. “While we do not know what will transpire when the C.V.A. window opens, at this point in time we have no expectation of needing to file for bankruptcy protection,” said Joseph Zwilling, a spokesman for the archdiocese. If anything, the one-year period in New York could spur even more lawsuits than have been filed in other states because sexual misconduct scandals have been dominating the national conversation. Accusations have mounted against religious institutions, elite private schools, sports programs, celebrities like R. Kelly and, most recently, Jeffrey Epstein, the wealthy financier who was facing federal sex-trafficking charges and hanged himself over the weekend in his Manhattan jail cell. In lobbying for the new law, advocates for abuse victims have highlighted the toll of sex abuse on children, and the decades it can often take before they are able to speak up about it, if they can at all. It took Charlie d’Estries years to process the sexual encounters that he said he remembered having with a priest as a boy. They were naked together, as he recounted it, and their relationship became sexual. Still, for decades, Mr. d’Estries, 64, did not describe it as abuse, and refused to see himself as a victim. But last year, when Mr. d’Estries returned to his Catholic school on Long Island for a reunion, a nun he had known as a student offhandedly called him “Billy’s buddy,” a reference to the priest. In a moment, he said, everything shifted. He was deeply shaken. He realized he had been abused. He was a victim. And he wanted justice, he said. But he discovered he could not sue until the law changed. “For 50 years, I totally set it aside,” Mr. d’Estries said on a recent morning, sitting in a park near his home in the suburbs of Buffalo. “The big piece is about being able to get it out. Let’s tell the story because it’s worth telling.” The look-back window, opening on Wednesday, allows Mr. d’Estries and other victims a year to bring cases, creating both an opportunity and a dilemma. Many victims described having to weigh, under tight time pressure, a yearning for justice and accountability against the pain that can be inflamed by reliving abuse in court. “The Child Victims Act opens the door to the courthouse,” said Michael Polenberg, vice president for government affairs at Safe Horizon, an advocacy group. “The Child Victims Act doesn’t change the way that our justice system works.” Lawyers have cast a wide net in their search for cases, blanketing television programs, newspapers and Google with advertisements. Some of the most prominent lawyers specializing in child sex abuse each have hundreds of cases to be filed as soon as the window opens, raising the prospect of overloading courts. “It’s unlike anything we’ve ever seen,” Jason Amala, a lawyer representing abuse survivors, said of the calls that have inundated his firm, including some from victims who were telling another person about their abuse for the first time. This year, far more than in past years, legislatures in nearly 40 states introduced proposals to expand statutes of limitations. New laws were enacted in 18 states and the District of Columbia. New Jersey was among them, passing a law that includes a two-year look-back window that opens later this year. “The significance of it is a switch in the balance of power,” said Marci A. Hamilton, the chief executive of Child U.S.A., a think tank focused on child protection at the University of Pennsylvania. “There was a severe imbalance of power that led to their abuse in the first place. The culture shut them out of the legal system until now. For them, this is validation.” The tectonic cultural shift also softened the opposition to the legislation. The institutions that had fought it were now praising the victims who had spoken up about their abuse and acknowledging the wreckage it has caused. “We believe victims,” the Boy Scouts said in a recent statement, “we support them, we pay for counseling by a provider of their choice, and we encourage them to come forward.” Still, the Boy Scouts, the church and others will soon be challenging victims’ accounts in court. Lawmakers in New York had tried and failed for well over a decade to expand the state’s statutes of limitations, which were regarded as among the most restrictive in the country. “We used to call New York a ‘shut down state,’” Mr. Amala said. Each time, the law’s supporters were thwarted in the Legislature by opposition from the Catholic Church, the Boy Scouts, Orthodox Jewish groups and the insurance industry. In years of jostling over the legislation, the look-back window had been the single most disputed element. The New York Catholic Conference said before the law passed that the look-back window would “force institutions to defend alleged conduct decades ago about which they have no knowledge and in which they had no role.” (Many of the clergy members named as credibly accused of abuse are dead, infirm or no longer affiliated with the church.) The State Assembly had passed the legislation multiple times, but before this year, the Senate never took it up for a vote. The political calculus in New York changed, however, after Democrats won control of the Senate in November. Before, victims often had severely limited avenues for financial redress, such as private arbitration that took place outside the courts. Catholic dioceses created Independent Reconciliation and Compensation Programs in which victims could apply for settlements. The agreements stipulated that the victims could not file lawsuits. The Archdiocese of New York, for instance, had reached agreements with more than 300 people, paying out $65 million, according to court records. The compensation program for the Diocese of Rochester was abruptly shut down earlier this year, with church officials citing the Child Victims Act as the reason. In future cases, the Child Victims Act allows prosecutors several more years to bring criminal charges, and decades more to victims weighing lawsuits. But advocates and lawyers stressed that the new law does not apply retroactively, meaning that virtually every abuse survivor older than 23 must bring any claims through the look-back window. In the Rockefeller University case, the endocrinologist, Dr. Reginald Archibald, who died in 2007, is accused of abusing scores of boys and teenagers. Rich Klein, who was a patient of Dr. Archibald’s, said he was eager to give voice to his account of abuse in court and force the hospital to listen. Suing “is a very easy decision for me because I want to do all I can — for the rest of my life — to send a message that this is not acceptable in our society,” Mr. Klein, 58, said. The Rockefeller University Hospital, through a spokesman, declined to comment. In a statement last year, the hospital acknowledged reports of “certain inappropriate conduct during patient examinations,” and sent a letter alerting about 1,000 former patients to the allegations. Some victims, like Dave Funk, said they were moving forward even though they could not remember their abusers’ identities. His lawyer, Michael T. Pfau, said Mr. Funk was pursuing litigation against the Diocese of Buffalo with the aim of sketching out details through the discovery process. Mr. Funk, 60, said it was only in recent years that he started coming to terms with his abuse. He was a student in a Catholic school in Buffalo, he said, when a lay choir leader took an interest in him. Their encounters started with hugs, kisses and back rubs, before escalating, he said. It ended when he moved to a public school. The Diocese of Buffalo declined to comment on Mr. Funk’s allegations, but said it was preparing for “the ramifications of the expected Child Victims Act claims.” Mr. Funk said he worked hard to get as far from being the vulnerable child he had been. He became an airline captain and owns farmland in Iowa, where he now lives. Still, he said he found that the abuse had an impact on his explosive temper and haste in ending relationships. The Child Victims Act, he said, forced him to confront his past and try to draw something from it. “I’m not going to be a victim of this guy for the rest of my life,” he said, adding that he hoped victims would feel empowered seeing him and others push past their shame and pain, and speak up. “Don’t do what I did and hide it forever.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.