|

Vermont’s dean of crime reporting helps keep secret specifics of priest abuses

By Colin Meyn

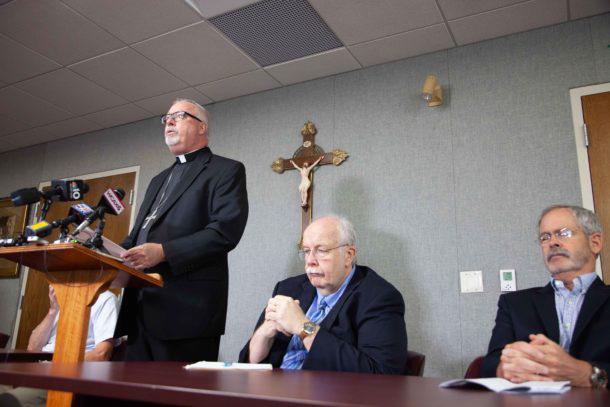

Mike Donoghue is used to asking tough questions about touchy topics and prying into sensitive affairs. He did that for decades as a staff reporter at the Burlington Free Press, where he boasted a rolodex with the home phone numbers of cops, police chiefs and defense attorneys. Since he left the Free Press in 2015, where he held the title of “First Amendment Reporter,” Donoghue has continued his career as a freelancer covering cops and courts for newspapers across the state. In his role as director of the Vermont Press Association, a post he has held for 32 years, Donoghue has championed the public’s right to know. Recently, however, Donoghue found himself on the other end of the tape recorder at a news conference, sitting next to Bishop Christopher Coyne, as the head of Vermont’s Catholic Church answered questions about a report naming 40 priests credibly accused of sex crimes against children. A total of about 400 priests have worked in the state since 1950, the diocese says. Donoghue, a devout Catholic, was part of a lay committee of seven members that reviewed reams of personnel files on priests who have been accused of sexual acts against children, bringing unprecedented transparency to an organization that for decades aggressively covered up its sins. The report also left many questions unanswered. How many children were abused? What sorts of abuse did they endure? What did the Catholic hierarchy know? Were abusive priests intentionally moved to new parishes? Donoghue had access to the files that could answer some of these questions. But he says he won’t talk about what he knows, beyond what’s in the report. His role has raised eyebrows among some editors, ethics experts and victim advocates who believe that he has acted hypocritically, tarnished his independence, or worse. Many news organizations have a policy that editorial staff cannot serve on boards or make political contributions to candidates, and most ask reporters to adhere to a code of ethics from the Society of Professional Journalists that sets standards for conflicts of interest. “He definitely has conflicting constituencies he’s trying to please,” said Ed Wasserman, a media ethics professor and dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. “And in his capacity as leading person in the press association he has a powerful interest in what the committee reports.” Wasserman said he appreciated Donoghue’s desire to serve both his religious and professional communities. “My sense of it is they’re not easily reconciled and his desire to do right by the church, you can think of a dozen ways that will conflict with his desire to do right by the public and this press association, of which he’s a leading figure.” Steve Terry, a former managing editor of the Rutland Herald (and a founding board member of the Vermont Journalism Trust, VTDigger’s parent organization), said he was disappointed that Donoghue, whom he has known and respected for decades, agreed to be on the lay committee. He said the impact of Donoghue’s participation in the report may radiate beyond that specific story — limiting the subject matters that editors and readers trust him to cover. “If it was embezzlement, fraud, all of those sort of economic crime areas, if I needed someone who could dig in and understand, I would still go to him for those kind of things,” Terry said. “But now we’re into sexual abuse and all of those crimes, which are quite prevalent right now, I would be probably reluctant … to hire Mike as a freelancer to cover those kinds of stories.” Terry said Donoghue may still feel that he is able to maintain his independence on stories about child abuse or sexual crimes. “But as you know it often depends on how the reader perceives that is more important than how you view yourself, and if the reader doesn’t have confidence then I’m afraid he has excluded himself from a certain area of crime coverage,” he said. In an interview on Sept. 13, Donoghue said he didn’t think his work on the priest abuse report conflicted with his work as a journalist. “A lot of people thought it was, you know, the bishop was wise to put me on there, as a nosy journalist,” he said. Part of the problem?David Clohessy, former director of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, has been highly critical of the Vermont lay committee’s report, arguing that names of predatory priests should have been released sooner, and there should have been more information about the number of victims and what the Catholic hierarchy knew about the abuse. Clohessy said the process was not something that Donoghue should have taken part in. “He should be ashamed of himself and I hope, frankly, the Vermont journalist community would denounce him for his recklessness and secrecy,” he said. The committee initially indicated plans to release its report in December 2018, but said members quickly realized that was unrealistic when they encountered the sheer volume of records — 52 files at the outset, each containing hundreds to more than a thousand pages. Clohessy said every day that names weren’t released put children at risk of being abused by those priests. “The minute Mike’s hand touched a document that showed a predator priest was an admitted or proven or credibly accused cleric, he should have raced to the bishop’s office and said ‘For the wellbeing of boys and girls, let’s get this out today,” Clohessy said. “And of course, every other committee member should have done that as well, but certainly a journalist.” Vermont’s journalism community has not denounced Donoghue, however. A half dozen editors declined to discuss on the record Donoghue’s dueling roles, and whether they presented a conflict, or didn’t respond to requests for comment at all. Others were supportive of Donoghue’s work on the committee. “At some point, semi-retired journalists are allowed to have a life outside the newsroom,” John Gregg, a longtime editor at the Valley News, said of Donoghue, who occasionally reports stories for the newspaper. “I find it a violation of his personal religious freedom to suggest that he should not participate in his church,” said Lisa Loomis, editor of the Valley Reporter and president of the Vermont Press Association. “Just because he saw the sausage being made doesn’t mean he has to reveal the recipe.” Donoghue said in a follow-up email that the committee took its time with the report because it didn’t want to falsely accuse priests or publish other inaccuracies. “We didn’t even want a comma out of place,” he wrote. “The committee makes no apology for trying to get the report right.” Donoghue declined to discuss decisions made within the committee about what to include in the report or what to keep out of it. But he said he would have produced a similar report if he approached the church’s documents as a journalist. And he said the reaction to the report spoke for itself. “We’ve received high marks from everybody, including victims that reached out to us, their families, supporters, the general public, some politicians, media members, you name it, they’ve all said it was a good job,” he said. Jan Leach, director of Kent State University’s Media Law Center for Ethics and Access, was more willing to accept Donoghue’s explanation of his involvement in the report, as long as he stuck with his commitment to never cover the issue of priest abuse as a reporter, and did not seek personal gain with the information he obtained in the process. “I would lean toward it’s not a good idea to do that,” said Leach, a former editor of the Akron Beacon Journal, noting that she is also a lifelong Catholic, but doesn’t sit on any boards of any kind. She said the greatest asset held by journalists is their credibility as an independent observer, which is undermined when journalists publicly align themselves with particular politicians, organizations or special interests they are also covering. “What matters is if you’re covering them, you shouldn’t have any relationship with them,” Leach said. But, she added, Donoghue had a “credible explanation” for his involvement in the priest abuse report, and as a freelancer did not need to worry about how it would reflect on the organization employing him. “You’re always treading a really thin line with these kind of things, and it’s hard. But a conflict is a conflict. I worry about perception as much as reality,” she added, “it becomes a question of the next person who pays him to write stuff.” Donoghue spoke about the lay committee review during an interview with Steve Pappas, editor of the Barre Montpelier Times Argus and Rutland Herald, on WDEV radio on Sept. 6. Pappas (who did not respond to a call seeking for comment for this article) asked Donoghue about the ethics of him applying his journalistic skills in service of the church. “But there have to be other journalists who were certainly kind of prodding you about this and saying, really, man, do you feel like now you’re part of the problem?” Pappas asked. “No,” Donoghue responded, “I think most people, I have to say, a lot of them were excited to hear I was on there thinking, you know, we might get to the bottom of it and everything like that.” “First, I was a human being. Second, I was a Catholic. And third, I became a journalist,” he added. “When I was approached about this, I said, hey, here’s a chance to put my investigative skills to work for the Catholic Church, who, you know, I’m a member of, so you know, we’re human beings first hand. I thought it’s a good chance to maybe help solve a problem more than being part of the problem.” Wasserman, the Berkeley professor, said Donoghue’s independence as an investigator was compromised before he even began the 10-month process of compiling the report. “By his own account — explaining his behavior by his desire to serve the church because he’s a devout and pious person — that’s already setting up a problem in that he’s acknowledging there are choices he would make that would prioritize his duty to the church over this duty to inform the public about this story,” Wasserman said. Wasserman added that journalists express their commitment to their communities through their work, “and of course we necessarily should be turning down assignments that put us in a situation with conflicting constituencies we are trying to please.” Active in retirementAfter Donoghue retired from his award-winning run at the Free Press in 2015, he hit the ground running as a freelancer, including occasionally writing for VTDigger. “I was just looking for something that, you know, like when I had my crown put on the other day, to be able to have some money to pay for it,” he said last week. Before long, he was writing 10 to 12 stories a week, he said, and doing just as much work as when he was still a staff reporter. Last year, he said he realized he needed to slow things down and decided, along with his wife, to take only a couple assignments a week. “Not quit completely cold turkey. But that was essentially the game plan. And it has worked for the most part,” he said. But Donoghue is still busy. He pushed back an interview with VTDigger because he was juggling three other projects and responding to press inquiries to comment on a Supreme Court decision finding that public records inspections should be free of charge. In the past few months, he has reported on a stepson facing gun charges linked to his stepfather’s killing, a man caught with a grenade and methamphetamines in his car, a straw man gun buyer sent back to jail after he attempted to overdose on heroin, and the final stages of Stephen Bourgoin’s murder trial. In May, he wrote about a “notorious convicted Vermont sex offender” sent back to prison after being found with child pornography. And in March, he covered “One of the most dangerous sex offenders in Vermont history,” who was released after 30 years in prison. And while Donoghue no longer works for the Free Press, his name is still listed on another newspaper’s masthead. He’s the lone staff reporter at The Islander, a weekly paper distributed to communities on Lake Champlain, both in Vermont and New York. Tonya Poutry, the newspaper’s publisher and editor, said she had no concerns about Donoghue’s role in the priest report. “The Islander and its readers are fortunate to have Mike do a little writing in retirement. Mike is not writing about the priest sex abuse case for The Islander – and somebody else covered it during his award-winning career at the Burlington Free Press,” Poutry said in an email. “Many people, including media members, thought Bishop Coyne was smart to appoint Mike to the 7-member independent review committee. The Bishop said he wanted transparency. Looks like he got it in the report,” she added. Questioning the reportNot everyone agrees with Poutry’s characterization of the report. The group that has been most critical of the committee’s work has been SNAP, which says the Burlington Diocese fell well short of full transparency and institutional accountability. Zach Hiner, SNAP’s national executive director, said the committee cannot claim to have reached independent conclusions when Bishop Coyne was still deciding what records they saw, and setting the general parameters of the report. “These lists are carefully cultivated and not fully transparent, not full of all the information that we as advocates would like to see, and hopefully someone who has spent their career promoting transparency would like to see on these lists as well,” Hiner said, referring to Donoghue. Donoghue has been the executive director of the VPA for more than three decades, according to his LinkedIn page, and is a board member of the New England First Amendment Coalition. Both organizations work to promote government transparency and public records access. Hiner said Donoghue’s involvement in the lay committee had obvious benefits to the Catholic Church’s public relations efforts around the report. “There’s a reason why they pick folks, to add legitimacy to their panel and also to sell the public that we’re doing this the right way,” he said. Bishop Coyne did not respond to emails seeking comment for this story. The bishop has taken a number of steps that victim advocates have long demanded, such as releasing accusers from past nondisclosure agreements and working with a local and state task force of police and prosecutors investigating the history of church-wide misconduct. Justin Silverman, a Massachussetts attorney who serves as executive director of NEFAC, the First Amendment group, said the organization was confident that Donoghue was a strong voice for transparency within the committee. “Claims of sexual abuse within the Catholic Church are of great public concern and NEFAC supports a robust dialogue about the committee’s report including any criticism that it didn’t disclose important information,” Silverman said in an emailed statement. “The failings of the report, if any, however, should be attributed to the committee as a whole and not one individual member,” he added. Other members of the committee included John Mahoney, a retired Burlington schoolteacher who was abused by a priest around eighth grade; former Chittenden County State’s Attorney Robert Simpson; Johanna Sheehey-Jones, a clinical analyst; Caroline Riehl Smith, a project manager at Dealer.com; and Mary O’Neil, principal planner for the city of Burlington. The committee chair was Mark Redmond, executive director of Spectrum, a social services nonprofit. Donoghue has publicly defended the work of the committee. “Transparency was promised and received,” he was quoted as saying in an article published on the Burlington Diocese website. “The bottom line is, I think we did as good a job as possible,” Donoghue said on WDEV. “We believe we were given as much information as they had, the Diocese of Burlington had.” And though Donoghue has declined to speak about specific decisions made by the committee, he says that he was a voice for greater disclosure. “One of the committee members said, you know, we would have been done a lot sooner if it wasn’t for Mike Donoghue, because he kept insisting that we go down this road or that road, or something like that,” he said on WDEV. Donoghue said in last week’s interview with VTDigger that he believed the committee’s list of priests credibly accused of sexual crimes against children was close to comprehensive. “My sense was, we might miss one. And I might be able to live with that. But if we missed two, I wasn’t gonna be happy,” he said. Clohessy of SNAP said he had little faith in the thoroughness of the report. “It’s based largely on information that was written down and preserved and vetted first — long before the committee was formed — by whom? The very Catholic officials who hid this for decades,” he said. Clohessy said his problems with the Vermont priest report were similar to those of reports being produced by dioceses-created committees around the country. “Honestly none of them have done the kind of job that they should,” he said. “There may be a few worse than Vermont, may be a few that are better, but only in slight degrees. Because let’s face it, bishops aren’t stupid, they’re gong to appoint to those panels only the most devout, cautious, obedient, trusting individuals.” Donoghue brushed aside the criticism from SNAP. “I realize they have the same questions, same quotes, in each state and each diocese. And that’s their shtick,” he said. “I understand that, you know, they’ve done a lot of good work. But as you know, from looking into them, they’ve also have some skeletons in their closet too.” Clohessy briefly stepped away from SNAP in 2016 after a former employee accused him of taking kickbacks from attorneys for abuse victims. He denied the charges and the case was settled out of court. Defending the churchDonoghue offered a general defense of the church’s response to priest abuse in his interview with WDEV, noting that he was not speaking for the diocese. He said Vermont’s diocese had created a safe environment office, staffed by prominent former law enforcement officials. And he added that the Catholic Church was not the only organization reckoning with claims of widespread child sex abuse, noting that the Southern Baptist Church, the Boy Scouts and the Boys and Girls Clubs of America were all grappling with claims that hundreds of children — or more — were abused under their watch. “So there’s a lot of large organizations, you know, it’s not just the Catholic Church, that they’ve got to look at how they’re structured,” he said. “But you know, how these others also are structured so that sex abuse of children,” he paused and Pappas finished his sentence, “stops.” Yet, the committee’s report did not wade into the church’s structure in any way, and critics of the church note that little has changed structurally since The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team started breaking stories in the early 2000s, cracking open a global story of systemic child abuse and institutional silence. The pope ruled in May 2019 that priests must report child abuse — until then it was up to their discretion. Donoghue said the committee kept a narrow focus on priests credibly accused or convicted of abuse, because that’s what they were asked to do by the church. He noted that Attorney General TJ Donovan and Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger opened a separate inquiry last year, which may be looking into the Catholic hierarchy’s role in crimes committed at the now-closed St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, the subject of a BuzzFeed investigation published last year. Donovan initially indicated it would be a statewide probe on par with what occurred in Pennsylvania, but other officials have indicated that the scope is limited to St. Joseph’s and Burlington. A page on the Attorney General’s Office website says the task force is “reviewing reports of alleged abuse committed by priests or others affiliated with The Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington and occurring in Vermont,” with a mind toward criminal prosecution. Donovan is in many ways retracing the steps of his predecessor, Bill Sorrell, who opened an investigation into church abuse in 2002 but decided, in the end, that all credible claims of abuse could not be criminally prosecuted because the statute of limitations had expired. If Donovan does find a way to bring criminal charges against senior figures in Vermont’s Catholic Church, it would be a major news story, not only in Vermont but across the country. It would be the kind of story, in almost any other scenario, that Donoghue would cover without a second thought. Contact: cmeyn@vtdigger.org

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.