|

Shifting the tide of rape culture

By John Breunig

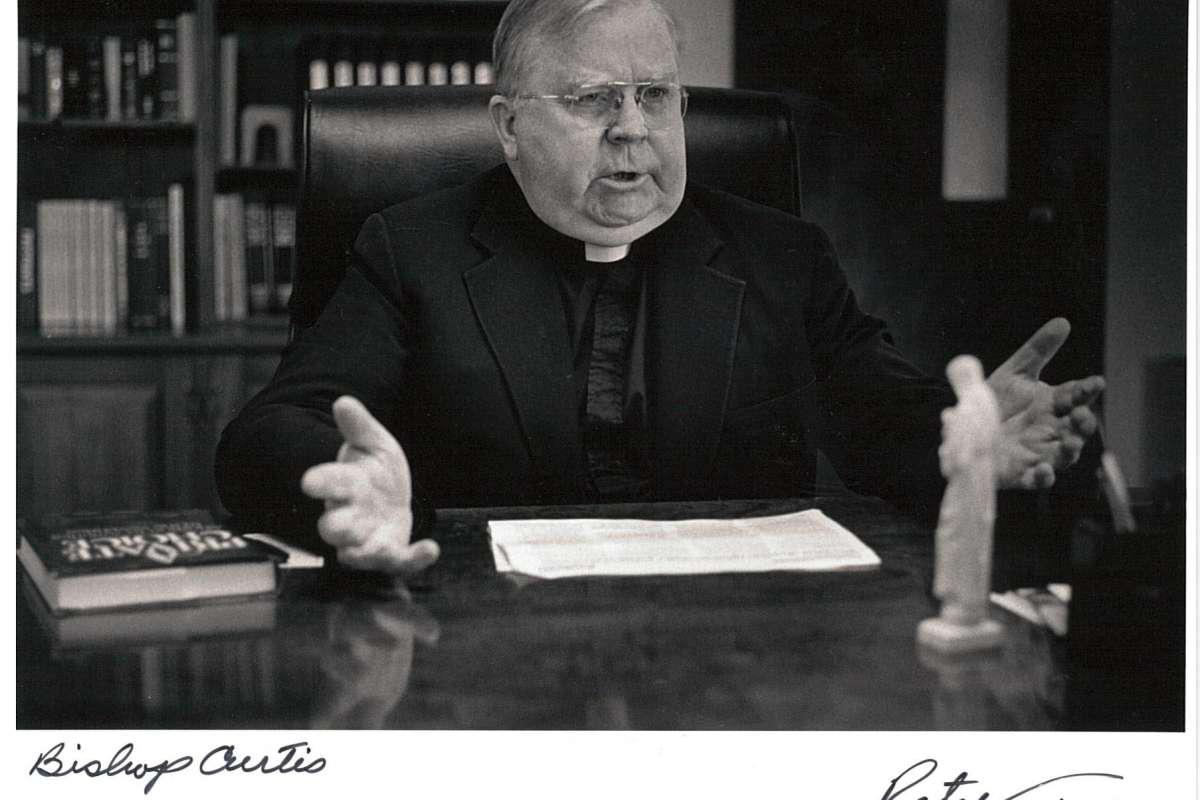

Luke Robbins has only been director of counseling for the area’s sexual assault resource center for a few days, so it almost seems unfair to engage him in conversation about the new report that exposes the depth of the Diocese of Bridgeport’s decades of covering up incidents of priests sexually assaulting children. The Stamford-based agency was recently rechristened The Rowan Center after The Rowan Tree, a symbol of resilience. Past banners signaled more clarity about the agency’s mission (such as the Center for Sexual Assault Crisis and Education). But I can respect that people, like Robbins, who do this for a living need to use metaphors, similes and euphemisms. I’ll take any euphemism over vile lies like the ones perpetuated in the diocese for a few generations. Robbins chooses his words with precision when I ask about his new job. “We walk with victims of sexual assault as they seek to ... start the process of ... mmm ... for lack of a better word I guess, processing what has occurred. And then to move on in a way that allows some of these terrible experiences to become a part of their story and not the title.” Every pause, every word is chosen out of respect for survivors. Retired judge Robert Holzberg and his team of attorneys lean on a few euphemisms themselves in the 250-page report commissioned by current Bishop Frank Caggiano. But beneath the poise of the language is a simmering fury. Caggiano got the candid investigation he sought. “Bishop Curtis prioritized the avoidance of scandal over the protection of people.” “Bishop Egan adopted a scorched-earth litigation strategy that ... re-victimized survivors.” “Bishop Lori’s reforms, effective and important as they were, were entirely management-driven.” One of the most damning observations is that “Bishop Egan demonstrated a remarkable lack of empathy for the suffering of victims.” Egan (who died in 2015) was promoted to archbishop of New York and a cardinal, making him one of the nation’s most powerful religious leaders. Caggiano recognized the need for an independent investigation. Gail Howard, co-leader of the Connecticut branch of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, suggested the diocese could have done more to draw out survivors through social media and by making pleas from the pulpit. If anything, more outsiders should be consulted. A good place to start would be The Rowan Center, which serves eight towns in lower Fairfield County, and its mirror agencies. Robbins offers a refreshing outsider’s view of his own. He immediately points out that someone who suffered from abuse during childhood could take decades before feeling comfortable enough to talk about it. Putting survivors at ease can include methods as simple as letting them choose where to sit. It’s also very nuanced. Too much sensitivity can backfire. Robbins compares it to over-medicating someone for depression. Sometimes, humans need to process sadness. Sometimes, a victim of sexual assault needs to appropriately recognize danger. “For someone who has been recently traumatized, every single piece of sensory information can feel like a threat,” Robbins says. I’ve written a lot about the work of the crisis center over the years, so it’s impossible to ignore that Robbins is the first staff member I’ve met who is male. Though most of the abusive priests cited in the report preyed on boys, the majority of clients at crisis centers are female. Robbins says “I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.” More men need to engage in the war on sexual abuse in all of its manifestations. Still, it poses challenges for the rare male in a sanctuary for female survivors. As a 6-foot tall, bearded man, Robbins is sensitive to the reality of how he might be perceived in the center’s solemn surroundings. “That can be an issue,” Robbins acknowledges. “It’s something we talked about and thought about before I was appointed. From a therapeutic standpoint ultimately our goal is to help someone move toward feeling whole again ... there are very few spheres in which someone can be successful and surrounded exclusively by one gender.” His team of four counselors do nothing less than try to re-calibrate human beings, to rewire their brains to come to terms with their trauma while allowing them to thrive. “We know more about the ocean than we know about the brain and we know almost nothing about the ocean,” Robbins says. It’s another metaphor, but it’s also blunt. There should be a lot more candor. There should be more outreach to crisis centers by the diocese and institutions like it. There should be more men like Robbins working to dismantle rape culture. Eventually, enough drops in the ocean can shift any tide. Contact: Jbreunig@scni.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.