Allentown Diocese Taps Little of Its $300 Million in Lehigh Valley Real Estate to Compensate Abuse Victims

By Emily Opilo

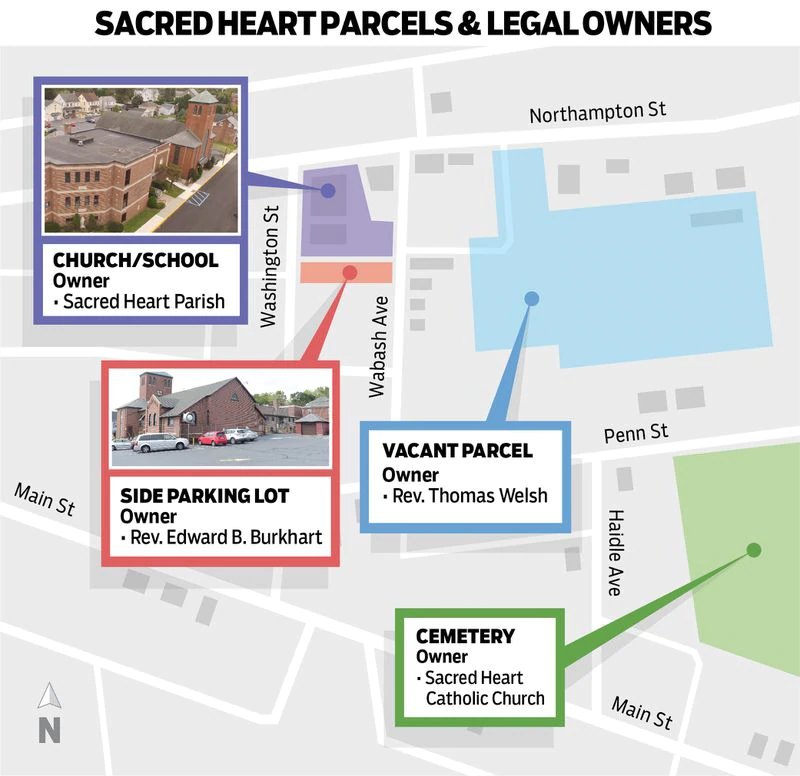

The title structure wouldn’t prevent the church from selling any of the land under its control, said Bethlehem attorney George Heitczman. And having a title in your name does not equate to ownership, he added. Deeds for numerous diocese-controlled properties reviewed by The Morning Call specify that the title holder has no personal rights to the property and stipulate that the bishop has the ability to sell each, regardless of whether they are titled in his name or that of his predecessors, parishes or pastors. “If the church wanted it done, it can be done fairly quickly," Heitczman said of a sale. “That’s not going to shelter them.” Where the title structure would make a difference is if the church were to declare bankruptcy, an option that has become increasingly common for dioceses across the United States. Since 2004, at least 18 Catholic dioceses or religious orders have filed for Chapter 11 relief, including the Rochester Diocese in New York last month. In Lehigh County, at least 29 diocesan parcels are held by Bishop Alfred Schlert, a structure recommended by church law. Property records show successive title transfers among bishops as each took control of the diocese. Schlert, who became bishop in 2017, holds no titles in Northampton County. But at least 15 diocese-controlled properties in that county remain titled to previous bishops including Welsh, who served from 1983 to 1997, and Edward Cullen, head of the diocese from 1997 to 2009. The bishops aren’t the only church officials who are title holders. There are nearly a dozen others, including Monsignor Robert Wargo who holds the title to St. Joseph the Worker School in Orefield, where he is pastor, and Monsignor David Morrison, a canon law consultant who holds the title for the parsonage at St. Francis of Assisi church in Allentown. Morrison was pastor of the church in the 1970s. Richard Serbin, an attorney who specializes in legal actions involving sex abuse by priests, said Allentown’s property structure and property movements mirror that of other dioceses. “They’re attempting to elude any judgments that might impact their assets by transferring property,” he said. “They’ve enjoyed immunity from lawsuits for years, and now they’re concerned about having to face a judicial system which is perhaps less forgiving and less deferential than they’ve enjoyed.” The numerous title holders and trusts wouldn’t make it impossible for a sexual abuse victim with a judgment to collect from the diocese, said Serbin, who represents several people who have entered claims with the Allentown Diocese compensation fund. But such “shenanigans” make it more difficult, he said. “It makes things tougher and longer,” he said. When a diocese goes bankrupt An onslaught of sexual abuse claims has transformed diocesan bankruptcy from a relatively untested process to standard procedure in a short time period. Marie Reilly, a professor at Penn State University who has studied diocesan bankruptcies, said past cases have almost always included a clash between the church and its creditors. Creditors look to maximize the scope of the church’s assets to boost settlements, and a diocese will try to minimize that pool, Reilly said. Having numerous titleholders complicates the process although it wouldn’t derail it, Reilly said. Dioceses are organized in two primary categories: corporation sole, in which the entire diocese is controlled from the top down; and separately incorporated, where each parish owns its own property. The Allentown Diocese is separately incorporated, according to financial statements to parishioners. In bankruptcy cases involving other separately incorporated dioceses, creditors have had little success getting parish property, Reilly said. In the event of a bankruptcy by the Allentown Diocese, Reilly said creditors could make a good argument to include properties titled to the bishop among diocesan assets. Properties with further removed title holders such as the parishes or priests would be more difficult to include, she said. Attorneys for creditors weigh the value of a property against the cost of a legal fight, Reilly said. A landlocked church in the Slate Belt that is titled to a priest might not be worth the fight. But a large parcel in the name of a parish in the Lehigh Valley suburbs might be. Allentown Diocese officials have not publicly stated nor signaled that they are considering bankruptcy. The Allentown Diocese’s holdings include another odd quirk — many of them have titles in the name of deceased church officials. In Northampton County, churches in Portland and Easton as well as a school in Bethlehem remain titled to Philadelphia Cardinal Dennis Dougherty, who died in 1951.

Notre Dame High School in Bethlehem Township is titled to John O’Hara, a Philadelphia cardinal who died in 1960, while the former Pius X High School in Roseto is held by Patrick John Ryan, archbishop of the Philadelphia Diocese from 1884 until his death in 1911. Nearly a dozen more properties are titled to Dougherty in Schuylkill, Carbon and Berks counties. Others are held by Ryan, Cullen, Welsh, McShea and John Barres, who preceded Schlert as bishop of Allentown. The deeds for some of those properties may have been transferred to various parishes but never publicly recorded, Reilly said. “You might not be looking at the whole picture," she said. “Or it might just be that bad.” Kerr said bishops and pastors remain the titleholders because they were in power at the time the land was purchased. They and their successors hold a property for the diocese, parishes or schools, he said. In a bankruptcy, creditors would argue that the Allentown Diocese effectively owns those properties by virtue of maintaining them for many years or paying taxes on them, Reilly said. Bishop’s house moved into trust Allentown isn’t the only diocese considering selling assets to grapple with the mounting cost of sex abuse-related bills. Across the country, dioceses and a few religious orders have been doing the same with some success. In 2004, the Boston Archdiocese, the first to be embroiled in the abuse scandal, sold its headquarters to nearby Boston College for more than $100 million to pay down loans used to finance sex abuse settlements. In 2011, the Burlington Diocese in Vermont did the same, selling its headquarters to Burlington College for $10 million. Bishops’ residences, often historic homes in premier neighborhoods, have also been a monetized asset. In March, the Buffalo Diocese announced it sold its nine-bedroom, six-bathroom bishop’s residence, for $1.5 million. In February, a rectory went for $1.3 million. Proceeds from both were used to cover sex abuse claims. In 2012, after a second Philadelphia grand jury investigation prompted criminal charges against a ranking church official and other priests, the Philadelphia Archdiocese sold its 16-room, 23,350-square-foot bishop’s mansion to St. Joseph’s University for $10 million. The Allentown Diocese has moved the 11-room, five-bathroom home at 2918 W. Chew St. in Allentown, where all its bishops have lived, into the priest pension trust. The property was purchased from then-PPL Executive William McHenry in 1961 for $100,000.

Today, the 5,000-square-foot brick Tudor Revival in Allentown’s West End is assessed at $487,000, according to Lehigh County records, and valued around $580,000. The Allentown Diocese also owned and operated an office at 1515 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in Allentown until it too was moved into a trust. The three-story, nearly 16,000-square-foot commercial space, purchased in 2011 for $1.6 million, houses numerous diocesan officials. It is valued around $1.7 million. The bishop’s office is not in the Martin Luther King Jr. Drive building but in a rented space at 4029 W. Tilghman St. in South Whitehall Township. The diocese also rents office space in Bethlehem Township, Upper Macungie and Lower Saucon townships. County records show the Martin Luther King Jr. Drive property was conveyed to the Diocese Lay Employees Retirement Plan Trust for $1 in December 2017, and the bishop’s residence was transferred for $1 to the Allentown Diocesan Priests Retirement Plan Trust in March 2018.

Both trusts were created on July 1, 2012, according to deed transfers for the properties. The trusts lease the properties back to the diocese, according to publicly filed “memorandum of lease” documents. A rental rate is not stated on the memorandums. Trusts have been used in other dioceses to reorganize assets. According to reports from the Erie Times-News, the Erie Diocese made numerous moves to compartmentalize its assets, including shifting properties into trusts both before and after the release of the grand jury report. There, the trusts were created in 2005, but property transfers were not completed until more than a decade later, church officials said, calling the timing an “unfortunate coincidence." In 2011, the Allentown Diocese began reducing pension benefits and in 2014, it began increasing its annual cash contributions, Kerr said. More than $7 million from the sale of a Krocks Road property was put into the lay employee pension fund in 2015, he said. In 2016, Barres, then the Allentown bishop, called for the Martin Luther King office building to be moved into the lay employees retirement plan, Kerr said, although the transfer did not happen until the next year. Schlert decided to transfer the Chew Street home, he said. The Morning Call requested an interview with Schlert for this story, but he declined. “The contribution of these two buildings to the pension plans strengthens the plans in two ways, by adding the asset value to the plans, and by providing on-going income generated by monthly lease payments made by the diocese,” Kerr said. At least two other Lehigh Valley properties under the diocesan umbrella are held by a trust: The former Hope United Church of Christ in Salisbury Township was purchased in 2018 for $1.4 million and is titled to the St. Thomas More Parish Charitable Trust. A nearby home purchased by the church in 2017 for $275,000, is also held by the trust.

In Berks County, the diocese sold a nearly 109-acre property in Exeter Township, titled to Schlert, to the St. Catharine of Sienna Parish Charitable Trust for $950,000 in June. The timing of the movement of properties into trusts and the amounts paid would be important if the diocese were to declare bankruptcy, Reilly said. Federal and state law set different windows of time when the transfer of assets can be questioned in bankruptcy proceedings. If a debtor is giving away property or selling it for less than market value during that period, it could be considered a fraudulent transfer, Reilly said. “A person has a powerful incentive to hide their assets,” she said, calling it a human urge. “The Diocese of Allentown can make a transfer and then kneel at the side of their bed and hope they don’t become insolvent or that their creditors don’t challenge that transfer until it’s beyond the reach [of bankruptcy law].” Schlert was aware that the property transfers would be public and open to scrutiny, Kerr said. “He proceeded with them as part of his commitment to continue to address the underfunding of the pension plans,” he said. While some dioceses have been quick to announce how many victims have been offered compensation and how much money would be paid out, the Allentown Diocese remains mum. Asked for a total after the fund closed last week, Kerr said the diocese won’t say until all the money has been distributed.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.