|

Responses to domestic violence in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)

By Katrina Pekich-Bundy

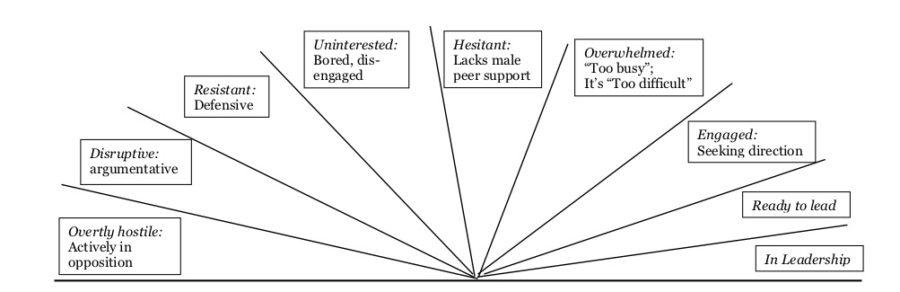

“Don’t walk alone at night.” “Always carry pepper spray.” “Never leave your drink unattended at a party.” “When walking alone in a parking garage, always put your keys between your fingers.” Most females have heard these recommendations at some point. They are the sacred conversations that happen from woman to girl — words of wisdom and warning. Grandmothers and mothers continue this oral tradition from generation to generation. The terminology and situation change over time. Now the conversation includes: “Never meet a man you met online in a private place.” The sentiments remain: Stay safe. Girls are taught this wisdom literature at a young age for survival, but why is the responsibility of safety only taught to girls? “Why aren’t we telling boys: ‘Don’t do these things’?” asks Rabbi Laura Metzger. A self-described “rabbi without walls,” she serves in a variety of settings in Louisville, Kentucky. Metzger recognizes men must be informed, too. Many of these warnings are to protect women from strangers — but what if, as is the case in too many situations, the abuser is someone known and trusted? Violence against women happens in all places, in all socioeconomic levels and in many ways – financially, emotionally, physically and more – yet humans struggle with how to break the cycle of violence. “Society often blames the victim to escape ourselves,” Metzger states, clarifying how these holy conversations are needed so that women are protected. For many years Metzger served in a synagogue. Years ago, she preached concerning the issue of domestic violence and received negative feedback about her message. But she knows that the message was important, because nearly 20 years later she still receives phone calls from people who heard that sermon and tell her that they are safe after escaping a violent relationship. Metzger became interested in confronting domestic violence when she was part of a group led by Nancy Troy, a pastor and one of the many advocates for the Presbyterians Against Domestic Violence Network (PADVN). PADVN is one of the 10 Presbyterian Health, Education and Welfare Association networks. Troy is currently minister at Briargate Presbyterian Church in Louisville. She spent many years educating others through workshops regarding intimate partner violence, and was ordained in 1998 to work at the Center for Women and Families. She noticed early on in her ministry that there was a lack of religious participation in domestic violence trainings. She began to work with Metzger and ministers in the United Church of Christ, the Lutheran Church and the PC(USA). One of those Presbyterian ministers was Bonnie M. Orth, pastor at Mayfield Central Presbyterian Church in New York. Orth and Troy were instrumental in organizing PADVN in 2001 and Orth testified at General Assembly that year to advocate for PADVN. “I call myself a ‘thriver’ instead of a ‘survivor,’” Orth said. Her own experiences with domestic violence and not receiving appropriate pastoral care from her minister fueled her advocacy for women’s rights. Now, Orth continues to train others in a variety of settings. Orth connected with Sandi Thompson-Royer, a mission co-worker serving in Guatemala. Thompson-Royer was involved in one of the first safe houses in the 1980s, where women could escape abusive relationships. When she went to Guatemala to serve, she wanted to avoid domestic violence work because she had done it for much of her life. Upon arrival she realized just how prevalent the issue is everywhere in the world. “God called me: ‘Sandi, this is what you’re meant to do,’” she remembers. She has educated both men and women in Guatemala about domestic violence. Space for storiesEducating faith communities is important. In 2015, Troy worked with members at Briargate to establish a workshop for community members, including government officials. The issue of domestic violence was especially pressing for the congregation because two women in the church had been affected: one had been killed by her husband and another was assaulted outside of a grocery store. The community was devastated. “We decided that we needed to try to make something good come from what happened in the past,” Troy said. Since that workshop she has created a space for women and men to feel comfortable talking about domestic violence, offering opportunities for the topic to be discussed through liturgy, sermons and workshops. Creating that space in worship offers a time to engage some of the misinterpreted Scripture passages and to identify how the Bible and culture meet in society. Was the relationship between David and Bathsheba consensual? Do we gloss over Rahab’s story because she was a prostitute? Why was Mary Magdalene considered a woman of ill repute for so long, when Scripture never suggests this? Engaging these stories offers an opportunity to break through misconception and for personal stories to begin to be shared. Many who have not experienced domestic violence question motives for not leaving a relationship. Just as all relationships can be complicated, the issue of domestic violence is fraught with other challenges. One can easily forget that a woman who is abused had, at one time, fallen in love with the man who became her abuser. Children might be involved and can be used in manipulation. Sometimes an abuser makes threats to a beloved pet or threatens to cut off a woman financially. Often an abuser will isolate the partner so that she is completely dependent on him. Advising a victim of abuse to “just leave” is not helpful. Unknown outcomesHana Elliott, a minister in the Presbytery of Ohio Valley in Indiana, was a resident advocate at Middle Way House, a domestic violence and rape crisis center in Bloomington, Indiana. She noted that issues of mental illness, addiction, disability and isolation all can impact whether a woman leaves an abusive relationship, and whether she returns. Domestic violence can include more than physical abuse. The core goal of an abuser is often to obtain power and control over a person and situation. Many social workers and women’s advocates use the Power and Control Wheel in order to understand the dynamics in an abusive relationship. The Power and Control Wheel was created in the early 1980s. This concept explains how the abuser will use any means necessary to control someone, including coercion, intimidation, emotional abuse, isolation, children, male privilege, economic abuse and blame. Sexual and physical abuse creates fear and reinforces the threats made by the abuser. Elliott states that one of the hardest parts of her job as a resident advocate was watching women return to the abusers. Her faith helped give her strength, as well as to offer hope to the women she met at the shelter: “My understanding of God’s eternal grace, unending compassion and persistent love helped me to keep working with some of the most difficult cases.” #MeTooA different urgency has arisen with the prevalence of the #MeToo movement. This past year we have heard the litany of men in the news who have abused or harassed women. Many men are surprised at the pervasiveness of these stories; some are now realizing that this is not just a “women’s issue.” Men are responsible for being educated on positive relationships with women and knowing the fears with which many women live. Women cannot continue to be brought up keeping our keys in our fingers in the parking garage or holding pepper spray in our bags. Rus Funk, a social worker and consultant, has spent 30 years working with boys and men in various organizations and training opportunities to educate, encourage and create space for conversations about ending violence against women. Funk began working in a domestic violence shelter during an internship while living in an all men’s dorm. He recalled noticing attitudes and behaviors of the men in the dorms as similar expressions to those of men who sought power and control over the women in the shelter. He realized that perhaps he could create more of an impact with men. “We want to see ourselves as good people,” Funk said. “In the words of a colleague of mine, men must come to terms with ‘how much like them I am.’” In other words, many men perceive harassment or abuse as a black and white issue: there are “those” men who abuse and everyone else. There is no room for gray, in which sometimes men make comments or actions that are considered microaggressions. Any unintentional action or comment that demeans a marginalized person is considered a microaggression. Of course, domestic violence is beyond microaggressions, but some may be introduced in the beginning of a relationship. These microaggressions are perhaps the mirror in which men see how they can be like “those” men: inappropriate comments or gazes that seem innocent but are not. Criticism of the #MeToo movement has noted that men who make a simple comment about a woman’s looks were grouped together with men who expose themselves in front of women. When all of these actions and comments are lumped together no one benefits. Funk sees this as a “very rich moment globally.” Conversations are taking place all around the world about gender equity. When considering how men will react to these conversations, Funk likes to use a continuum. Some men fall on the far end of the continuum and will be hostile and defensive. Funk believes now is the time to engage those who are more in the middle of the continuum — those who he identifies as “hesitant” because of a lack of support or “overwhelmed” because they already are engrossed in a variety of other issues. With support and conversational space these men have the opportunity to work toward gender equality. Recently Funk has focused on leading faith communities in discussions, training congregations in skills needed to help women who are in abusive relationships. His goal is to help churches change policy and culture so that they can create spaces for conversations. Not only can churches create healing for the women who have been abused, but they can also be accountable to the abuser, making sure they find resources to help them end their abusive behaviors. Churches struggle to be involved with domestic violence shelters because of issues of confidentiality and the amount of training it can take to understand the layers and responses to abuse. Yet, that doesn’t mean churches can’t make an impact. Donations are usually accepted, including food, clothing, supplies and money. Elliott shared that many churches brought these items to Middle Way House, including goodie bags for the children living in shelter with their mothers. Troy and Funk emphasized the importance of helping women in violent situations seek professional help to keep them safe. Those who support PADVN are no longer paid. The staffing has changed but the need for education and change still exists. Now is the time to act. The world is in the midst of an awakening in which we must believe survivors of sexual abuse and domestic violence. Churches must take a stance. Now is the time to end violence against women.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.