|

Catholic Archdiocese of Vancouver aware of 36 cases of clergy sex abuse since 1950s, CBC learns

By Laura Clementson And Gillian Findlay

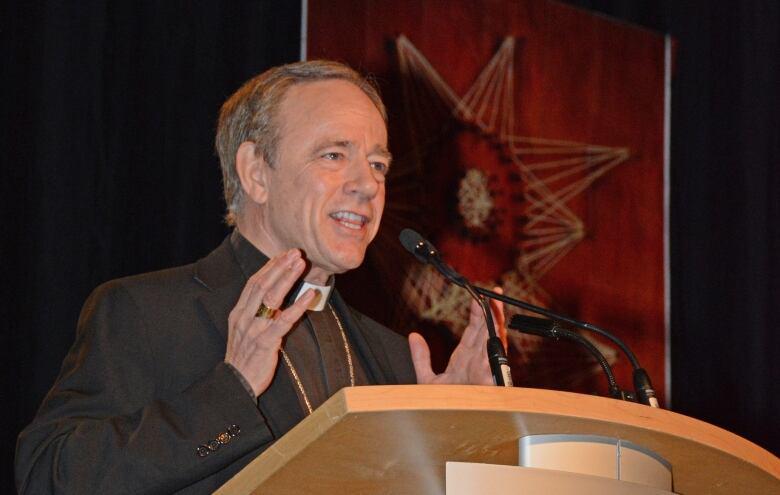

[with video] The Catholic Archdiocese of Vancouver was aware of 36 cases of abuse by clergy under its jurisdiction, including 26 involving children, results of an internal review of cases of clergy sexual abuse obtained by CBC's The Fifth Estate show. The review, commissioned in 2018 by Archbishop Michael Miller, examined church files dating back to the 1950s. No Catholic entity in this country has ever made this kind of information public before. The Vancouver review also found three of their priests had fathered children. I think that the church has an ethical and moral responsibility to reveal those names.- Leona Huggins, clergy sexual abuse survivor The information was uncovered in a Fifth Estate investigation into how the Catholic Church has dealt with abuse allegations over the years. Vancouver's archbishop has not released the results of the case review committee's work, but in February he promised transparency. In a letter posted to the archdiocese website, Miller committed "to correcting any systemic flaws that contributed to abuse or cover-up." The Fifth Estate investigation also reveals details about how the archdiocese handled allegations of abuse. Some accused priests moved jurisdictions, and some went for treatment instead of being referred to police. In some cases, victims were paid money and had to sign confidentiality agreements. The information shows that church officials often knew of credibly accused perpetrators and yet did not share that information with the community at large. Being "credibly accused" does not require that someone be convicted of abuse, only that the church believes there is enough evidence to believe an incident took place. In addition to reviewing the cases, the committee produced 31 recommendations, including that the names of clergy deemed credibly accused be released publicly. "I think that the church has an ethical and moral responsibility to reveal those names," said Leona Huggins, an abuse survivor Miller asked to join the case review committee. 'I was just horrified'The committee was made up of church-appointed individuals from different professions, including clergy, lawyers and laypeople. Four members are described as victim-survivors of clergy abuse. As an elementary school teacher, Huggins said her highest priority is the safety of children, and that's one of the reasons she felt compelled to take part in the review. Huggins was living in New Westminster, B.C., in the 1970s when her parish priest, John "Jack" McCann, started sexually abusing her. She was 14. Growing up in a Catholic household of 12 children, Huggins and her family welcomed the attention McCann paid to them, especially when Huggins and one of her sisters were asked to work in the rectory. Huggins said the abuse started subtly, when McCann would wrap his arm around her or put his hand on her leg. It then advanced to shoulder massages. Huggins said "it was gradually more and more," and eventually led to sex. It wasn't until 1991, two decades later, that she revealed the abuse to police. McCann pleaded guilty to sexual offences involving Huggins and another teenaged girl and spent 10 months in jail. Huggins believed that was the end of McCann's career as a priest. But in 2011, she discovered the priest who sexually abused her was working in a church in Ottawa. "I was beside myself. I was just horrified. I was pacing up and down in my kitchen and just going … like, this is not okay," said Huggins, who volunteers with the Vancouver chapter of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP). When SNAP revealed McCann's criminal past, the Archdiocese of Ottawa revoked McCann's duties. He died in August 2018. Tallying sexual abusersSexual abuse by clergy members has dogged the Catholic Church for years. Scandals have been uncovered in the U.S., France, Germany, Australia, Chile, Ireland and other countries. In some jurisdictions, efforts have been made to tabulate the number of abusers and victims. In the U.S., for instance, 6,800 clergy members have been deemed credibly accused by their own church. For the first time, we can begin to understand the systematic cover-up by church leaders.- Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro In 2018, a damning grand jury report in Pennsylvania named more than 300 priests as having abused more than 1,000 victims in six dioceses. It marked the first time a major governmental agency in the U.S. conducted such an investigation of the Catholic Church, according to Thomas Doyle, a canon lawyer in Virginia. "What they did [was], they got warrants from judges to march into the chancery offices of the various dioceses, and take their files," said Doyle, a priest himself who now helps lead the worldwide campaign to hold the Catholic Church accountable. "There was no discussion, there was no debate: 'We're taking [the files], get out of the way.' And that's what [the Pennsylvania Attorney General's office] had to do. So they blasted away one of the major defences." The Pennsylvania probe also revealed how much church officials knew about the abuse and what they did when allegations came forward. "For the first time, we can begin to understand the systematic cover-up by church leaders that followed," said Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro in a press conference in August 2018. "These documents from the diocese's own secret archives formed the backbone of this investigation, corroborating accounts of victims and illustrating the organized cover-up by senior church officials that stretched, in some cases, all the way to the Vatican." Since Pennsylvania, at least 17 other U.S. states have started their own investigations. Some Catholic dioceses in the U.S. have released their own lists of abusers voluntarily. Archdiocese to make some info publicIt was in the aftermath of Pennsylvania that Vancouver's Archbishop Miller struck his case review committee. Information obtained by The Fifth Estate shows many of the accused clergy the committee looked at are now dead, but not all. It confirmed one priest the committee looked into still lives in proximity to students. The Fifth Estate asked Archbishop Miller for an interview to comment on the committee's findings and recommendations, but he declined. Names and numbers of Catholic priests that abuse children … that's the kryptonite of the Catholic Church- Rob Talach, London, Ont. Lawyer On Nov. 12, legal counsel for the archdiocese sent a letter to The Fifth Estate stating, "Certainly there have been settlements paid over the years in response to the wrongdoings of clerics in the Archdiocese of Vancouver. We are not aware, however, of any allegations which would support your claims that there were priests who had committed offences who were transferred, that authorities were not appropriately notified, or that priests remained in proximity to children after they were found to have committed an offence." The archdiocese said it will be making some of the information from the review public on Nov. 22, but would not say whether it will include the names of clergy it has deemed credibly accused. The committee recommends the archdiocese share names, birth dates and photographs of accused priests, as well as dates and locations of their assignments. Rob Talach, a lawyer in London, Ont., who has taken the Catholic Church to court more than 400 times for sex-related abuses, said that publishing the "names and numbers of Catholic priests that abuse children … that's the kryptonite of the Catholic Church, [but] to ask them just to hang it out on the internet isn't gonna happen." To date, none of Canada's 60 Latin Rite archdioceses and dioceses have made information about convicted and credibly accused priests public. Unlike in the U.S., no provincial attorneys general have pressured them to do so. The Fifth Estate surveyed the other 59 dioceses in Canada, asking whether they have conducted their own reviews of past and present clergy "who have faced/are facing credible allegations of sexual abuse." Only 14 dioceses responded. Of those, four said they have conducted reviews and one said it is in the process of doing so. None of the dioceses surveyed said they were prepared to make the information public. Since September, The Fifth Estate has been requesting an interview with anyone from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops to address the issue of clergy sexual abuse. In a Nov. 9 email, the CCCB responded, "Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, we regret that a representative of the CCCB is unable to participate in the program." A week later, it posted a statement on its website that it called an update to the implementation guidelines on protecting minors from abuse. "The tragedy of clergy sexual abuse is and will continue to be addressed with utmost seriousness and respect by the Catholic Bishops of Canada," the Nov. 15 statement read. It emphasized that it is up to individual dioceses to make their own decisions but said church officials are meeting with survivors of abuse and considering the calls for making the names of credibly accused abusers public. "There remains an important question to consider related to the publication of names of the 'credibly accused' who have not been charged and convicted," the statement said. "It is evident that a simple 'yes' or 'no' answer cannot be given to such a complex matter when seen through the lens of privacy laws, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the well-being of victims-survivors." It also underlined the year-old policy requiring church officials to notify police if they are informed of allegations of current abuse of a minor.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.