|

Alexander Brunett, Seattle archbishop who oversaw expansions amid burgeoning sex-abuse scandal, dies at 86

By Lewis Kamb

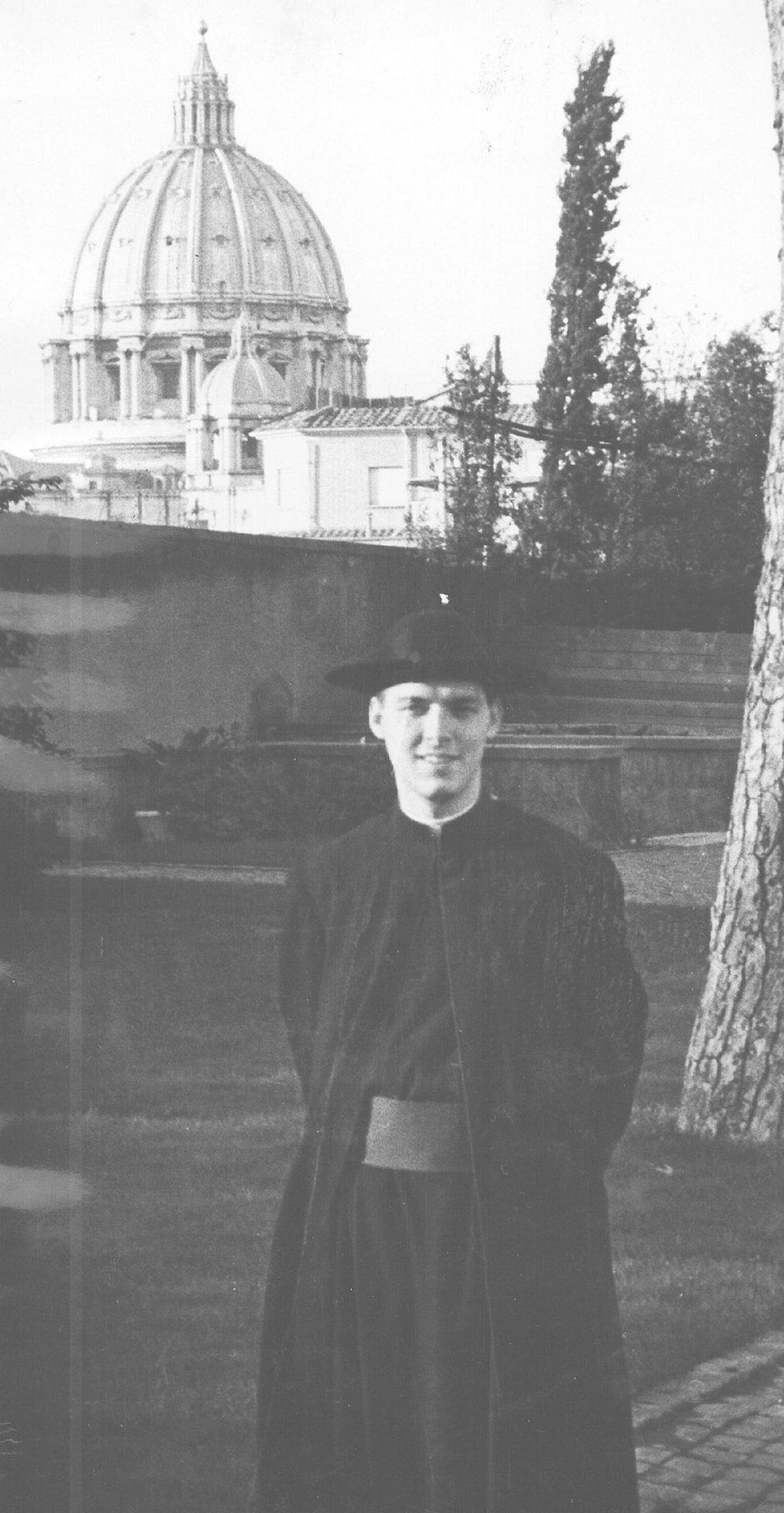

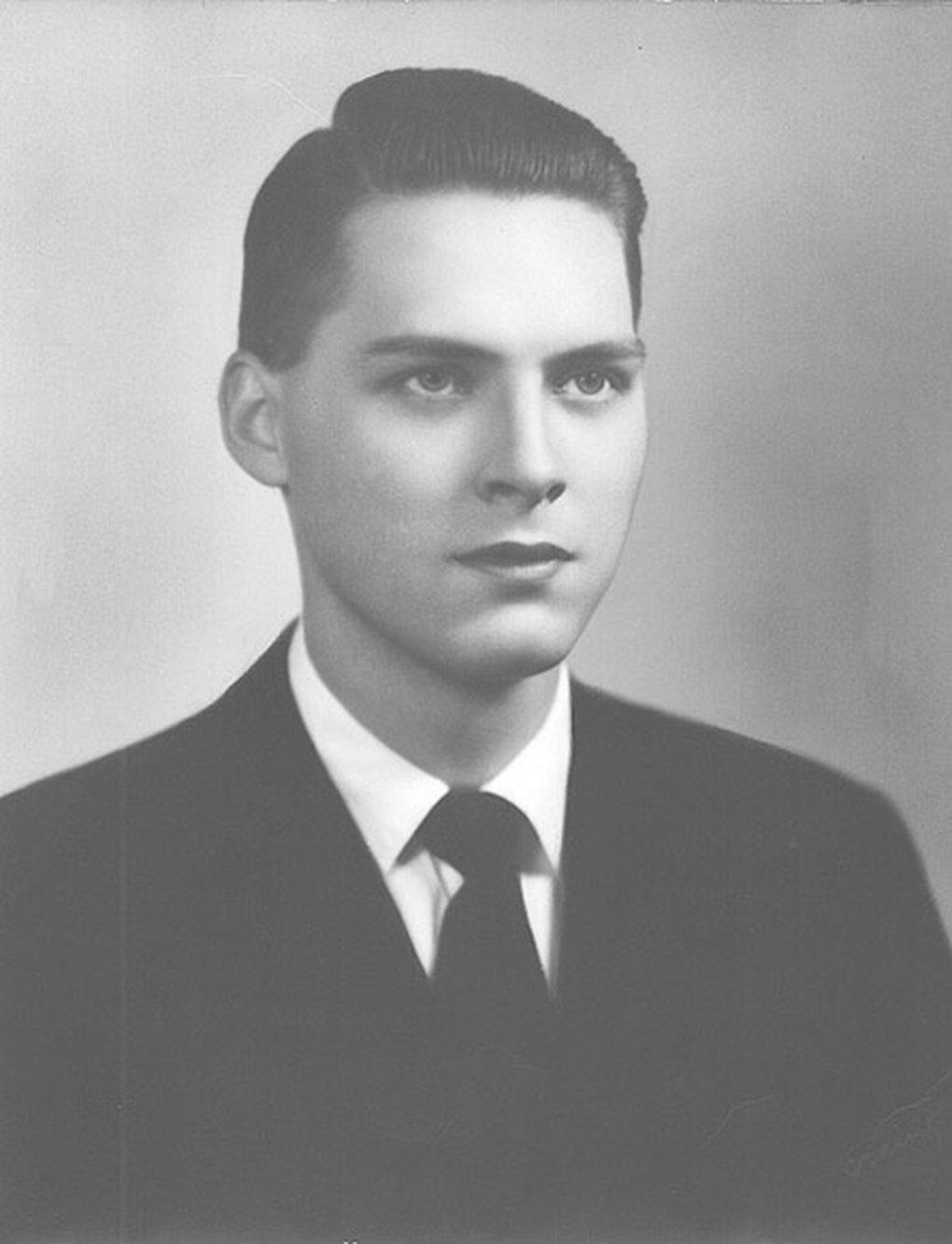

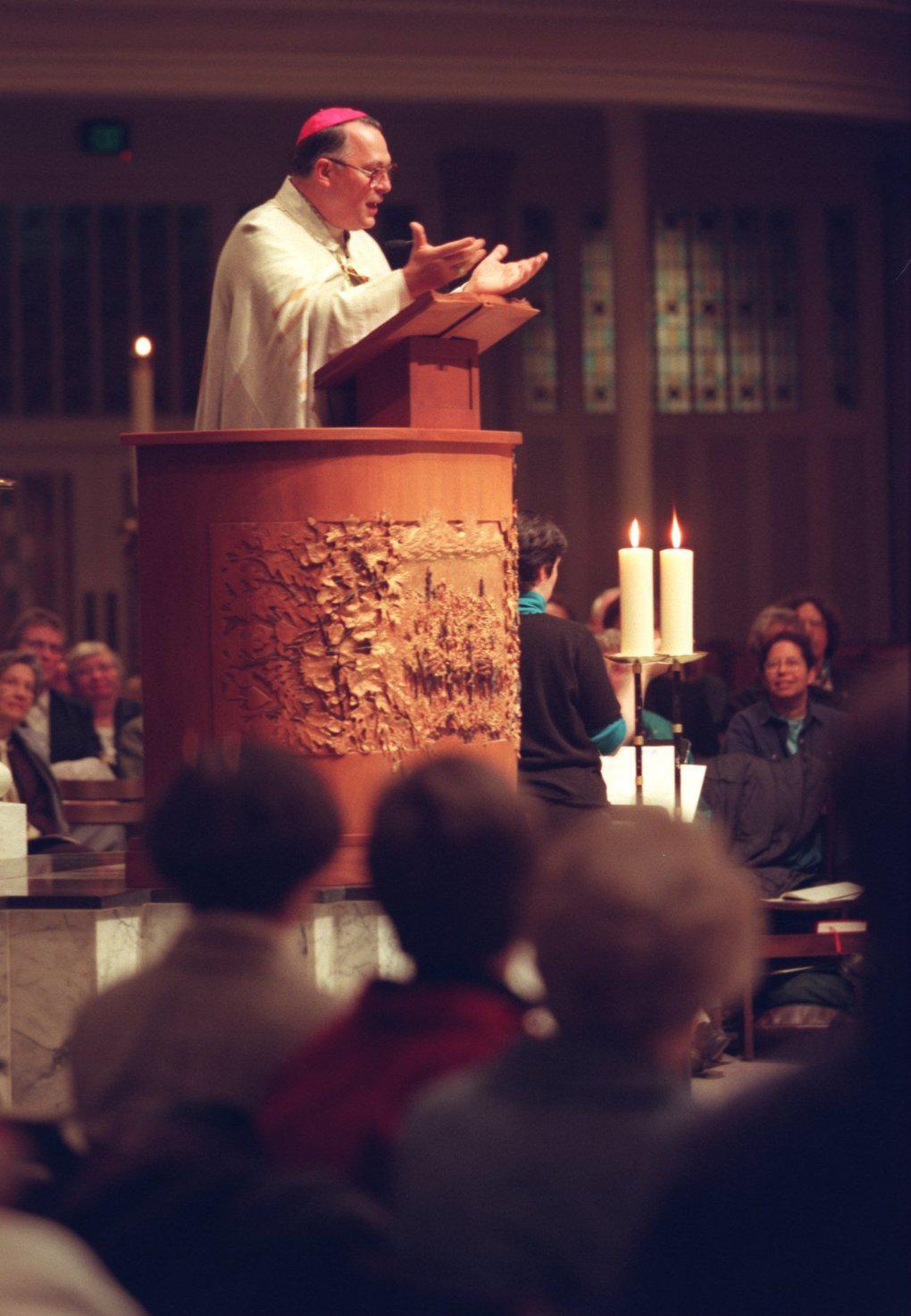

Alexander Brunett, an assertive, retired archbishop of the Seattle Archdiocese who led an aggressive expansion of schools, parishes, charities and scholarships as a clergy sex-abuse scandal exploded into public consciousness, died in Seattle on Friday. He was 86. Brunett, who grew up in a large family in Detroit and eventually ascended from a parish priest to bishop, retired after 13 years as Seattle’s fourth archbishop in 2010. His health had declined since a stroke in 2013 left him partially paralyzed, and since suffering head trauma during a fall in April, church officials said. During the height of his tenure in Seattle, Brunett pushed a public-affairs strategy aimed at making the church a force in public life. He made headlines by fighting King County’s attempts to limit the size of new churches in rural areas, and challenged the Legislature to support higher wages for home-care workers and expand protections of the Columbia River watershed. He also joined other church leaders in admonishing The Seattle Times’ decision to hire replacement workers during a seven-week newspaper strike by the Pacific Northwest Newspaper Guild. “I’m more an advocate for those who don’t have a voice,” he said in an interview with The Times in 2001. “I believe the profile of the church should be a little stronger — that people should know who we are and what we believe.” But political adversaries criticized Brunett’s style as heavy-handed, and some Catholics viewed him as more obstacle than advocate for clergy-abuse accountability efforts. In a December 2004 letter to Brunett, several prominent members of a review board called him out for ignoring recommendations for more transparency and accountability for perpetrators and improved safeguards to reduce further abuse. Born the second of 14 children on Jan. 17, 1934, in Detroit, Brunett was ordained in 1958, serving as a parish priest, pastor, university chaplain and seminary dean in the Archdiocese of Detroit. In 1973, he was named the ecumenical officer for the Detroit Archdiocese and was instrumental in starting a national Catholic-Jewish dialogue that received various awards and commendations as a pioneering interfaith endeavor. Pope John Paul II appointed Brunett bishop of Helena, Montana, in 1994, and after Seattle’s Archbishop Thomas J. Murphy died three years later, the pope named Brunett his successor. Church officials remembered Brunett as a vibrant, down-to-earth prelate who loved to compete — both on the golf course and while heading the archdiocese’s day-to-day operations. His tenure in Seattle was partly marked by economic recession and rising health care, priest-pension and employee costs. But he nonetheless led widespread fundraising initiatives, doubling annual contributions by local Catholics and advancing several building projects, including construction of Seton Catholic College Prep in Vancouver, Washington, and Pope John Paul II High School in Lacey. “He literally built up the church in Western Washington, building new high schools and opening up a number of new parishes,” said John Hempelmann, a Seattle real estate attorney and close friend. “He was a giant of our lifetime that came from very humble beginnings, but he never really left being a parish priest.” Brunett’s determination helped launch in 2002 the Fulcrum Foundation, a local endowment that provides scholarships for poor children to attend Catholic schools, and he orchestrated the $7 million purchase, renovation and expansion of the Palisades Retreat Center in Federal Way, which in 2011 was renamed the Archbishop Brunett Retreat and Faith Formation Center. He also co-chaired the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission in 2004 with publication of “The Seattle Statement,” the first joint international statement of understanding by two Christian communions on the place of Mary in the doctrine and life of the church. “In many of these [initiatives] people said it couldn’t be done,” recalled Mary Santi, chancellor of the Seattle Archdiocese who worked closely with Brunett. “His response was simply, ‘No, it can be done. It will be done.’ And he was right. He just had a certain vision and wouldn’t easily give up.” Under Brunett, Catholic Community Services (CCS) also burgeoned into one of Western Washington’s largest social service providers, serving more than 10 million meals, providing nearly 2.2 million nights of emergency shelter, opening 1,101 new units of affordable housing, and offering 21 million hours of services to the elderly and disabled, according to CCS President Michael Reichert. Brunett’s passion for Catholic charities was born from an upbringing during the Depression, Hempelmann said. “He told me a story once about when he was a kid; that it was because of Catholic charities he was able to get a new pair of shoes,” he said. “He never forgot that.” Brunett sparked a national controversy in 2004 when he announced he would not automatically deny Holy Communion to Catholic politicians who supported abortion rights, but put the onus on them not to seek Communion in the first place. The archdiocese credited Brunett for “implementing policies and procedures for child protection and outreach to past victims of abuse.” But members of a board reviewing clergy sex abuse butted heads with the archbishop in 2004. The group’s review supported accusations against nine priests, and recommended that a 10th — the Rev. Harold Quigg — also be defrocked for having an “egregious” sexual relationship with a teenage boy. Brunett resisted publishing the board’s report and wanted it rewritten, contending the members had exceeded their charge and that most of the recommendations were already in place. He relented, but only after board members threatened to resign. But the list published by the archdiocese didn’t include the name of Quigg, who continued to carry out ministry work. Ten years later, after Brunett had retired, parishioners learned of the allegations against Quigg and the matter blew up into a scandal, forcing then-Archbishop Peter Sartain to bar Quigg from public ministry. But Brunett’s recommendation to the Vatican about the Rev. John Cornelius — accused by more than a dozen men of abusing them during childhood — resulted in late 2004 in what’s believed to be the first priest to be laicized, or defrocked, in Western Washington. On his 75th birthday in 2009, in accordance with canon law, Brunett submitted his letter of retirement to Pope Benedict XVI. The pope later called Brunett out of retirement to serve as an apostolic administrator at the Diocese of Oakland, California. Shortly after returning to Seattle to live, Brunett suffered a stroke in 2013. Though partially paralyzed, he continued to show up at events around the archdiocese as archbishop emeritus, even attending a gala dinner a week before his death, Hemplemann said. “I always enjoyed my visits with the archbishop, and found him to be joyful, grateful, and always ready to pray and give his blessing,” Seattle’s new Archbishop Paul Etienne said in a statement. “These are true hallmarks of any disciple of the Lord, and we are grateful for his presence and service in the Archdiocese of Seattle.” Funeral arrangements are underway, church officials said. Contact: lkamb@seattletimes.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.