|

“The Two Popes” Gives Way to Pope vs.. Pope on the Issue of Celibacy in the Priesthood

By Paul Elie

New Yorker

February 2, 2020

https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-two-popes-gives-way-to-pope-vs-pope-on-the-issue-of-celibacy-in-the-priesthood

|

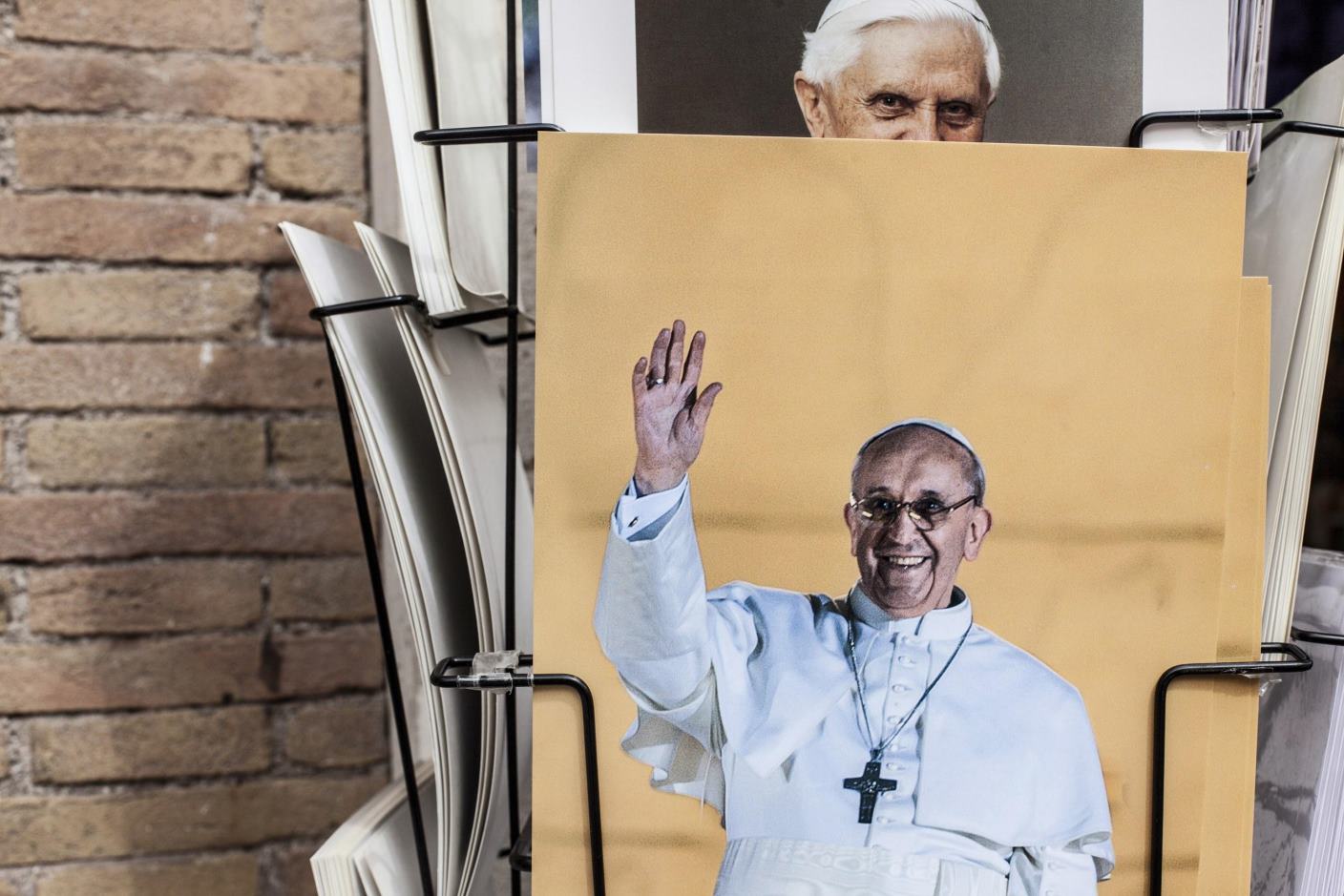

The conflict between traditionalists and progressives in the Roman Catholic Church has hardened around Popes Benedict XVI and Francis and tipped toward an open dispute.

Photo by Alessio Mamo |

Of the many fanciful scenes in the movie “The Two Popes,” the most striking is one set in 2012, in which Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the future Pope, from Argentina, teaches Benedict XVI, the current Pope, from Germany, how to tango. Bergoglio (Jonathan Pryce) has spent two days in private meetings with Benedict (Anthony Hopkins). No such encounter took place, but the screenwriter dreamed it up in order to present the very real differences that have emerged between the progressive Bergoglio and the traditionalist Benedict over the future direction of the Church. When the time comes for Bergoglio to depart, the men exit the papal apartments, via a tourist-thronged Sistine Chapel, and go to where a black Mercedes-Benz is waiting to take Bergoglio to the airport. Apropos of nothing, Benedict points out that even the radical Saint Francis of Assisi, Bergoglio’s future namesake, got some things wrong. Bergoglio replies that the saint loved to dance and suggests that if he’d lived in modern times he would have done the tango. “Come, I’ll show you,” he says. The camera moves in, and they dance: two men, both past threescore and ten, one in black, one in white, face-to-face, hand-in-hand, lurching across the paving stones.

Nobody’s tangoing at the Vatican at the moment. “I Due Papi,” as the film is titled in Italy, is giving way to Pope vs. Pope. Benedict’s resignation, in 2013, the first by a Pope in nearly seven hundred years, brought about the unusual circumstance of the Church’s having two living Popes. After Bergoglio was elected to succeed him, Benedict promised to keep silent, and with a few exceptions—an interview here, a letter there—he has done so. All the while, however, he has received traditionalist clerics at his residence, a small monastery behind St. Peter’s Basilica, and some of them leave with his apparent blessing to oppose Francis on the latter’s various progressive initiatives—on divorce, immigration, inequality, or inter-religious dialogue. The conflict between progressives and traditionalists has hardened around the two Popes; it tipped toward an open dispute in recent weeks, with the publication of a book that presents one Pope indirectly rebuking the other on an issue that has long divided the Church and is now up for consideration in Rome: the question of priestly celibacy.

The current dispute began last October. As an Argentinian, Francis has given particular attention to the Global South, and, at his prompting, the Vatican hosted a “special synod” of bishops from around the world to discuss issues, such as climate change and human-rights abuses, affecting the people, especially the indigenous population, of the Pan-Amazon region—and the future of Catholicism there. The region encompasses parts of nine countries—an area that is home to 2.8 million people, who speak some two hundred and forty languages. Priests are scarce in the region, so bishops close to Francis proposed setting aside the rule that priests must be celibate, in order to ordain married men “of proven character,” so that they can celebrate the Eucharist at Mass, an act reserved for priests alone.

Traditionalists saw the proposal as a backdoor move by which progressives would engineer an eventual end to mandatory celibacy worldwide. One of them was Cardinal Robert Sarah. Born the son of a farmer in Guinea, Sarah was ordained a bishop in 1979, at the age of thirty-four (becoming the youngest Catholic bishop in the world), and has held a series of top posts; in 2014, Francis appointed him the head of the Vatican’s Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. But the Cardinal—who is known for his practice of going to a remote place from time to time to fast for three days, in order to “recharge and to return to battle”—has since emerged as Francis’s most formidable adversary in the Vatican.

Then, on January 15th, Editions Fayard, in Paris, set out the Cardinal’s views on celibacy in a book credited to two authors: Sarah and, with top billing, Benedict XVI. The book’s title, “Des Profondeurs de Nos Coeurs” (“From the Depths of Our Hearts”), suggests an intimate collaboration between the two men. Progressives immediately charged that Benedict had broken his silence in order to undermine Francis—who will soon release an apostolic exhortation on the Amazon, in which he is expected to endorse the optional celibacy proposal—or that Sarah had contrived to involve Benedict, who is ninety-two and infirm, in his opposition. In response, Sarah posted letters on Twitter in which Benedict discusses his contribution to the book. The letters are printed on Benedict’s letterhead, but progressives have pointed out that there is no saying for sure that Benedict composed them. Several days into the conflict, Archbishop Georg Gänswein intervened. Gänswein serves two masters: his formal role is prefect of the papal household—a nominal chief of staff to Pope Francis—but he lives in Benedict’s residence, and serves as his personal secretary and gatekeeper. He said that Benedict had only contributed an essay to the book, not collaborated on it, and that the Pope emeritus wants his name taken off future editions. It had all just been a “misunderstanding.” Progressives took that statement as evidence that Sarah had manipulated Benedict; traditionalists took it as evidence that a “furious” Francis had forced Benedict to strike his name from the book. Ignatius Press, the San Francisco-based publisher of a forthcoming English-language edition of the book—and of dozens of Benedict’s books through the decades—said, perhaps with an eye on sales, that it would keep Benedict’s name on the cover. Either way, genuine or contrived, the collaboration gambit drew worldwide attention to Sarah’s arguments.

From one page of the book to the next, though, it hardly matters how involved Benedict was in its drafting—Sarah is steeped in his thought and that of his traditionalist predecessor, the since canonized Pope John Paul II, and cites them both throughout. For Sarah, and for Benedict and John Paul, and for traditionalists generally, to even consider ordaining married men is to “relativize the greatness and importance of celibacy” and that of the priesthood as a whole. In Sarah’s account, a priest is fundamentally a man apart; he makes a gift of himself “to God alone.” He renounces sex, marriage, and family life for the sake of his bride, the Church. To propose any other model of priesthood is to capitulate to the forces that Benedict, when he was still Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, termed the “dictatorship of relativism.” Those who speak of ordaining married men, Sarah writes, are “sorcerer’s apprentices,” who want to give the people of the Amazon “second-class priests,” as part of a “neo-colonialist plan” to deprive them of Catholicism in full.

Pope Francis, for his part, hasn’t addressed the question of celibacy directly. The final document of the synod on the Amazon presents the prospect of ordaining married men as a response to an urgent need that “calls for opening new pathways for the Church in the territory.” It explains that the effort would tap only men who are already ordained as deacons, “to sustain the life of the Christian community” in remote areas, by enabling them to celebrate the Eucharist at Mass. But the move took shape in light of Francis’s conviction that the Church needs to adapt to circumstances. “A fire does not burn by itself; it has to be fed or else it dies; it turns into ashes,” he said in a homily at the opening of the synod. “If everything continues as it was, if we spend our days content that ‘this is the way things have always been done,’ then the gift vanishes, smothered by the ashes of fear and concern for defending the status quo.”

It is this unprogrammatic openness to change that has agitated the traditionalists ever since Francis was elected. In a forthcoming book, “The Outsider,” Christopher Lamb, the Vatican correspondent for the progressive British Catholic journal The Tablet, sets out a “Timeline of Opposition” to Francis. It has about a hundred entries, among them the joint efforts of Steve Bannon and Matteo Salvini, Italy’s far-right former Deputy Prime Minister, to mark Francis as the “enemy” on immigration, and the theatrics of the runaway Vatican diplomat Carlo Maria Viganò, who, after Francis withdrew him as papal nuncio, or ambassador, to the United States, published a seven-thousand-word letter in which he called for the Pope’s resignation. Thirteen entries involve Cardinal Sarah. As the traditionalists see it, Francis has given up on the notion that the Church can and should transform society. In fact, he is all for the transformation of society. On immigration, inequality, and the environment, he has called for fundamental change more forcefully than any other world leader. (His efforts to lead change within the Church are more moderate: he has sought a reform of the Vatican bureaucracy and closer scrutiny of its finances. After truculently dismissing claims of priestly sexual abuse in South America—and facing fierce criticism for doing so—he has since vowed to take a hard line against sexual abuse in the Church.) He urges Catholics to embrace the good wherever they find it, whether or not it has the sanction of Rome. He aims to be as open to new possibilities for the Church in the twenty-first century as Francis of Assisi was in the thirteenth.

Progressives find it disconcerting that traditionalists—sticklers for decorum in liturgy, clerical dress, and the like—are so brazen in their opposition to this Pope. But it’s an unavoidable consequence of Benedict’s stepping aside. His resignation changed the nature of the papal office from a lifetime role to a time-stamped opportunity. It changed the nature of Vatican governance from courtly fealty to something like a coalition, in which a Pope pursues certain objectives by mustering support, heading off challenges, and raising up a prospective successor to whom he can cede power by resigning when the historical moment and the electoral calculus seem right. And it has changed the nature of Vatican conflict. When John XXIII, a now sainted progressive Pope, initiated the Second Vatican Council, he said that he sought “an opening of the windows.” Such an opening has inadvertently been brought about by the traditionalist Benedict. The Vatican that was a fortress of secrecy, where conflicts were dealt with behind closed doors, is gone. Francis’s adversaries will keep speaking out against him, whether or not they have a Pope emeritus to lend lustre to their arguments.

What should Francis do about them? He could remove them through the exercise of the papal office, which he has been disinclined to do—and which can have unintended consequences, as in the case of Archbishop Viganò. He can let them age out, as he did with Archbishop Charles Chaput, of Philadelphia, a voice for traditionalists who bemoan the “confusion” of Francis’s pontificate, whom he replaced last week, soon after Chaput reached the nominal retirement age of seventy-five. Or he can engage them in dialogue, as he will likely try to do through the exhortation on the Amazon. At some point, Francis—or his successor—is going to have to address the rule of priestly celibacy as it applies worldwide. Meanwhile, the drama of the two Popes makes clear that the different factions in the Church have to find ways to resolve conflicts without invoking papal authority.

|