|

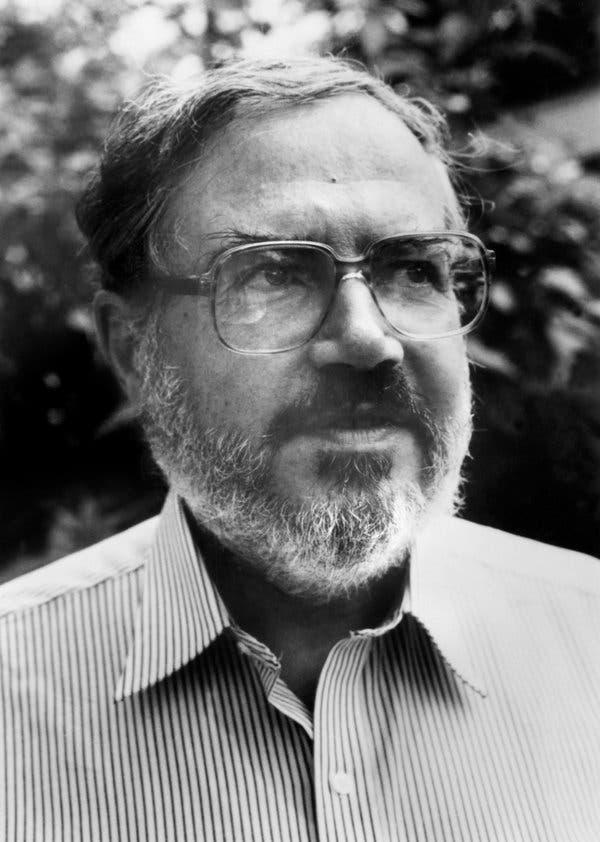

Dr. Leonard Shengold, 94, Psychoanalyst Who Studied Child Abuse, Dies

By Richard Sandomir

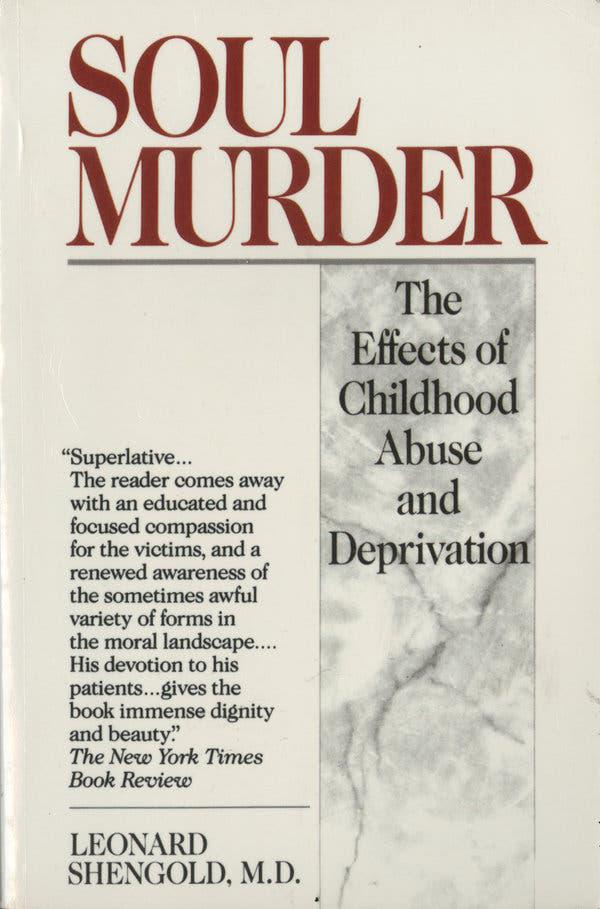

He said mistreating and neglecting children amounted to “soul murder” — a deliberate attempt to crush or eradicate the personality of a vulnerable young person. Dr. Leonard Shengold, an esteemed psychoanalyst who in two books vividly described the terrifying impact of long-term abuse and neglect of children as “soul murder,” died on Jan. 16 at his home in Stone Ridge, N.Y. He was 94. His son David said the cause was complications of leukemia. During 60 years of psychoanalytic practice, Dr. Shengold observed the damage childhood abuse had wreaked on numerous adult patients. (He also treated patients outside that category, including the renowned writer and neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks.) He described “soul murder” as a crime committed by psychotic or psychopathic parents and other adults through sexual abuse, emotional deprivation and physical or mental torture. He equated this mistreatment with the “deliberate attempt to eradicate or compromise the separate identity of another person,” as he wrote in “Soul Murder: The Effects of Childhood Abuse and Deprivation” (1989). Dr. Shengold had been treating adult victims of childhood abuse for about 25 years when he wrote “Soul Murder.” The term that gave the book its title was coined in the 19th century and later found its place in a noted case history of Freud’s based on the memoirs of a mentally ill judge. Dr. Shengold drew on decades of clinical cases and the literary works of writers like Kipling, Chekhov and Dickens, all of whom, he wrote, suffered neglect or abuse in childhood. Helpless children, he believed, are easily victimized by their tormentors because of their physical and emotional dependence on them. And their reliance on them inevitably compels many to seek solace from the abusers themselves. “The most destructive effect of child abuse is perhaps the need to hold on to the abusing parent or parent figure by identifying with the abuser,” he wrote. “This becomes part of a compulsion to repeat the experiences of abuse — as tormentor (enhancing sadism) and simultaneously as victim (enhancing masochism).” In her review in The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani wrote that Dr. Shengold had created a “modern scientific definition” of soul murder and written “a provocative study of an all-too-common phenomenon.” Dr. Harold Blum, a psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who was a colleague of Dr. Shengold’s, said that “Soul Murder” and its follow-up, “Soul Murder Revisited: Thoughts About Therapy, Hate, Love, and Memory” (1999), were valuable in capturing the psychological depth of abuse and asserting the importance of unconscious fantasies in understanding traumatic experiences. “Len was well aware that the impact of trauma was modified by unconscious fantasies, and that one never got a totally accurate depiction of a traumatic experience,” Dr. Blum said in a phone interview. Leonard Shengold was born on Dec. 5, 1925, in Syracuse, N.Y., to Chaim and Sonia (Kosofsky) Shengold, both of whom had immigrated from cities that were part of the Russian empire at the time. His father, a watchmaker, came from Minsk; his mother, a homemaker, was from Vilna. Leonard was 5 years old when his father started experiencing severe angina attacks, prompting his mother to caution him, “You mustn’t get him excited; it might kill him,” he recalled in an interview with the International Forum of Psychoanalysis in 2011. “And as soon as she said that, I could tell from her face how distressed she was to have said it. She started to cry, and I started to cry. Perhaps I had an early talent for empathy.” His father died seven years later. Leonard, a bookish youngster, attended Syracuse University for one semester before transferring to Columbia College in New York, where one of his teachers, the literary critic Lionel Trilling, sparked his interest in Freud and psychoanalysis. At 18 he entered the Army, where he served as an air-to-ground radio operator in India and then as a clerk in North Africa and Saudi Arabia after the Japanese surrender. He took two books with him to the war reflecting his literary and scientific interests: Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past” and Freud’s “Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis.” He graduated from Columbia in 1947 with a bachelor’s degree in English and earned a medical degree at the Long Island College of Medicine (now SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University) four years later. He received training at the Psychoanalytic Institute and Clinic at Downstate (now the Psychoanalytic Association of New York, which is affiliated with the New York University School of Medicine). Over his 60-year career, Dr. Shengold saw patients privately; was a training analyst at the institute, as well as its director from 1975 to 1978; and taught psychiatry at N.Y.U. He received the Sigourney Award, for work advancing psychoanalysis, in 1997. “He was a very coveted and highly regarded supervisor,” said Dr. Blum, who was also a training analyst at the institute. Dr. Shengold’s other books include “Haunted by Parents” (2006), about childhood influences that make people resist change, and “If You Can’t Trust Your Mother, Whom Can You Trust? Soul Murder, Psychoanalysis, and Creativity” (2013), about the central influence of parents. But it was his articles in journals about “soul murder” and the publication of the book based on them that transformed his career. “I was sent many patients who at least felt they had been sexually abused as children, and I learned how different they were in spite of many similarities,” he told the International Forum of Psychoanalysis. “Now, after so many more years and the publication of seven other books, I still get these calls, and it is almost always ‘soul murder’ that they mean.” In addition to his son David, Dr. Shengold is survived by his wife, Margaret (Wheeler) Shengold; a daughter, Nina Shengold; another son, Larry; and three grandchildren. Although Dr. Shengold was known for his studies of child abuse, he had a general practice. While he was reluctant to talk about his patients by name, he was proud when in 1985 Dr. Sacks dedicated his book “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” to him. Dr. Shengold began treating Dr. Sacks in 1966 for an amphetamine addiction. He continued to see him for nearly a half-century. “Above all, Shengold has taught me attention,” Dr. Sacks said in an interview in 2012 for the website Web of Stories, an archive of stories told by prominent scientists and other people. “And what is sometimes called listening with a third ear — listening to what is behind the babble.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.