|

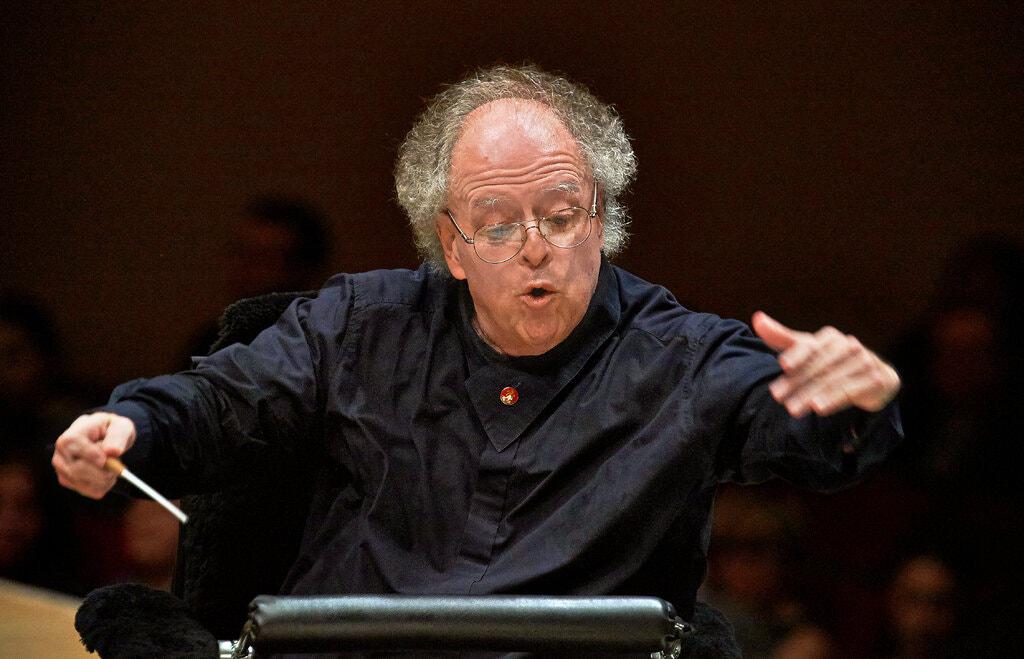

The Met Opera Fired James Levine, Citing Sexual Misconduct. He Was Paid $3.5 Million.

By James B. Stewart And Michael Cooper

The terms of the settlement between the renowned conductor and the company he shaped have not been previously disclosed. Last summer, Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, convened the executive committee of the company’s board to announce the end of one of the highest-profile, messiest feuds in the Met’s nearly 140-year history. A bitter court battle had concluded between the company and the conductor James Levine, who had shaped the Met’s artistic identity for more than four decades before his career was engulfed by allegations of sexual improprieties. Mr. Gelb told the committee that the resolution was advantageous to the Met. But the settlement, whose terms have not been publicly disclosed until now, called for the company and its insurer to pay Mr. Levine $3.5 million, according to two people familiar with its terms. The Met had fired Mr. Levine in 2018 after an internal investigation uncovered what the company called credible evidence of “sexually abusive and harassing conduct toward vulnerable artists in the early stages of their careers.” Rather than going quietly, Mr. Levine sued the company for breach of contract and defamation, seeking at least $5.8 million. The Met countersued, revealing lurid details of its investigation and claiming that Mr. Levine’s misconduct had violated his duties. It sought roughly the same amount. A year later, and after millions of dollars in legal fees on both sides, the company agreed to pay Mr. Levine, though millions less than he had sought. The terms of the settlement have not previously been disclosed because a confidentiality agreement has kept both parties from revealing its details. The Met’s multimillion-dollar payment to Mr. Levine came before the coronavirus pandemic forced the company to close its theater — leaving many employees, including its orchestra and chorus, furloughed without pay since April. Even when the deal was struck, the Met’s finances were precarious. Now the company is fighting for its survival. The size of the payment to Mr. Levine, whom the Met had accused of serious misconduct, casts doubt on the strength of the company’s case had it gone to trial. Mr. Levine’s contract, which had been amended over the years but was essentially based on agreements struck decades ago, lacked a morals clause, an increasingly common feature in the entertainment world that prohibits behavior with the potential to embarrass an employer. It has not been uncommon for high-profile figures forced from their jobs after accusations of sexual misconduct or harassment to leave with big payouts, often to satisfy the terms of their contracts. Two of Fox News’s most prominent personalities received large payments after they were forced out amid allegations of harassment: Roger Ailes, the network’s former chairman, got about $40 million when he left, and Bill O’Reilly, one of Fox’s biggest stars, received roughly $25 million. But it is rare for someone who leaves under pressure because of sexual misconduct allegations to publicly challenge the firing in court. In his suit, Mr. Levine had sought $3.4 million for breach of contract after the Met stopped paying his $400,000-a-year salary as music director emeritus, just a year and a half into a 10-year agreement. He also sought more than $1.6 million for the remaining performances he had expected to conduct during the season he was fired and the season following, as well as $707,500 for defamation; he argued that the Met’s statements about him led other orchestras to fire him and cost him a book project. And he sought other, unspecified amounts for defamation, pain and suffering, and attorney’s fees. Before the Met’s investigation and Mr. Levine’s firing, it appeared that Mr. Gelb had succeeded in easing the revered but ailing maestro into a dignified career coda, making way for Mr. Levine, now 77, to be succeeded by the young and dynamic Yannick Nézet-Séguin. After ill health forced Mr. Levine to repeatedly cancel performances and miss two full seasons, he had reluctantly agreed to become music director emeritus. He would continue to oversee the young artist program he had founded and to conduct many of his signature operas, with a gala celebration of the 50th anniversary of his 1971 Met debut on the horizon. Mr. Levine’s continued role came at considerable cost to the company. In addition to his $400,000 salary, the Met agreed to pay him his customary $27,000 fee for each performance he conducted — $10,000 more than what the Met usually described in public as its top fee. That arrangement came to an abrupt end in December 2017, after The New York Times published the accounts of four men who said that they had been sexually abused by Mr. Levine as teenagers; Mr. Levine denied the accusations. Coming at the height of the #MeToo movement, the accounts caused a furor, and the Met suspended Mr. Levine without pay and began an investigation. Other orchestras and festivals immediately cut their ties with him, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Ravinia Festival outside Chicago, where he had longstanding relationships. After a three-month investigation, in which its lawyers interviewed over 70 people, the Met fired Mr. Levine in March 2018, saying the investigation had uncovered additional troubling incidents and that it would be “inappropriate and impossible” for Mr. Levine to continue at the Met in any capacity. The company resisted paying Mr. Levine severance, or any money owed under his existing contract. Although Mr. Levine’s lawsuit included defamation claims — all but one of which were later dismissed — it was essentially a breach of contract suit. With no morals clause, about the only basis for ending the agreement, apart from rare acts of god that would prevent the Met from functioning, was Mr. Levine’s death or disability. But, armed with the findings of its investigation, the Met countersued. It cited seven unnamed people who had been the victims of what it called “sexually abusive and harassing conduct.” Mr. Levine was undeterred by the potentially embarrassing public disclosures. People familiar with his thinking said the conductor, who has never publicly discussed his sexuality, felt he could rebut the allegations. And he was already so humiliated that he felt he had nothing further to lose by litigating. The Met did not name any of the seven accusers. But one of the men in the Met’s court filing was identified by Mr. Levine’s lawyers as Ashok Pai, whose account of being molested by Mr. Levine as a teenager figured prominently in articles in The Times and The New York Post. Another accuser was a longtime Met employee who, the Met said, Mr. Levine had propositioned while wearing a bathrobe and had subsequently “inappropriately touched” at least seven times between 1979 — when the man was 16 and auditioning for Mr. Levine — and 1991. In a third incident, from 1985, the Met said Mr. Levine had driven an opera singer home from an audition, then locked him in the car and groped and kissed him against his will, later placing him in “a prestigious program” at the company. In another incident reported by the Met, Mr. Levine asked an artist if he “had a large penis.” Mr. Levine’s lawyers denied all the allegations, and were eager to question witnesses under oath, and to ask the Met’s leaders about other sexual improprieties at the company over the years and the degree to which they had been tolerated. The Met’s lawyers zeroed in on another sensitive area for Mr. Levine, demanding his medical records. Just as depositions were about to begin in earnest, the parties agreed to submit the case to mediation. Even then, tensions ran high as Mr. Gelb and Mr. Levine faced one another at the opening session, according to two people familiar with the proceedings. An exasperated Mr. Levine even left the session before being persuaded to sign off on the $3.5 million agreement. The resolution was announced publicly on Aug. 6, 2019, just days after the end of the Met’s fiscal year. As a tax-exempt nonprofit institution, the Met files annual disclosure statements that include revenues and expenses, as well as specific large payments to independent contractors, such as Mr. Levine. But filings for the period in which the Met paid Mr. Levine are not due until mid-2021. The agreement included a strict nondisclosure clause. The Met’s announcement said only that the case would not go forward. Details were kept to a small circle at the Met and the top echelons of its board. Board members were told that insurance would cover the company’s litigation costs, which in fiscal year 2019 amounted to more than $1.8 million, some of it related to the Levine investigation. Insurance also covered more than $900,000 of the payment to Mr. Levine, the two people familiar with the settlement said, leaving the Met responsible for roughly $2.6 million. Since the settlement was reached, Mr. Levine has been living in California, and has taken the first steps to try to revive his career. He is planning to return to the podium in Italy, a country which has proved hospitable for musical stars accused of sexual misconduct, and is scheduled to appear in January in Florence. The opera? Berlioz’s “La Damnation de Faust.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.