|

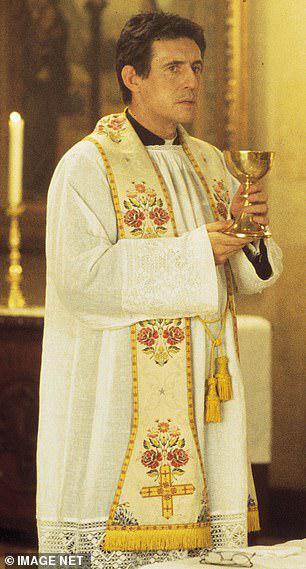

'I wanted the priest who hurt me to be terrified and burn in hell for ever'

By Gabriel Byrne

Actor Gabriel Byrne reveals a terrible secret and how he tried to confront his tormentor Surrounded by a moat, the Christian Brothers' School House for Older Boys was a fine old Irish castle from the 13th Century. The ghost of Oliver Cromwell was said to walk its stairways and corridors, and Queen Elizabeth I once slept in the stone chamber where we had our classes. In 1961, when I was ten years old, a curate visited and announced to the class: 'Boys, I want to talk to you about vocations to the priesthood. A vocation is a word from Latin meaning 'to call'.' God might be calling you, he said. 'And if he is, you must answer.' I thought of God trying to get through to me on the phone. The curate continued: 'If you listen to the voice deep inside yourself, in quiet moments, you will hear him. To be chosen is the greatest gift any family could have.' The curate showed us slides of missionaries in straw hats, flying planes, crossing rivers and jungles in faraway countries such as Bolivia, living a life of adventure like they were in The Hotspur comic. He passed photographs around the class: smiling men surrounded by laughing children. I stood under a map of the world, pointing to places I had never heard of: Papua New Guinea, Tobago, Liberia. And sure enough, I began to hear God. It started as a feeling. And it became more and more real and insistent. The curate gave me a magazine with an article about a seminary in a village near Birmingham, far away in England, which received boys my age who wished to train for the priesthood. There were photographs of them playing snooker and football, and of older boys studying in their own rooms, surrounded by shelves of books as sunlight streamed in through the windows. My own room. In our house, I shared a bed with my two brothers, while my three sisters slept together in another room across the hallway. 'Put up your hands, the boys who would like to follow the Lord. To save the souls of heathens.' I saw myself, in that moment, on a horse, in a straw hat, a snow-capped blue mountain behind, crossing rivers full of crocodiles, hacking my way through jungle. I raised my hand. I left for the seminary one night in October. Neighbours and family came to the house to give a little party for my departure. They pressed coins and notes into my hand, miraculous medals to keep me safe for the journey on the night mailboat across the Irish Sea. My father had promised to be home before I left, but when it came time there was no sign of him. I heard my mother whisper that he couldn't face saying goodbye, and he'd be in the pub waiting until we were well gone. I realised for the first time how much I would miss my family. Now I wanted nothing more than to stay, not leave for another country to become a priest at 11 years old. I thought of my father teaching me to ride a bicycle, how he held on to the saddle as I wobbled the handlebars. How by the fire in the early morning we would listen to the radio, to the fights from Madison Square Garden. Or how he would wake me at dawn to go out in the still-asleep world beyond the town to pluck mushrooms from dewed grass. We'd fill the bucket, then go home to a feast, sizzling in the butter of the pan. 'We better be off or this fog will be down on us,' said Mr Lyons, the neighbour who was to drive my mother and me to the boat. 'Is there any sign of him?' 'Perhaps he won't be able to leave if the fog comes down too thickly.' Then my father came like a ghost out of the fog, swaying slightly. He shook my hand, told me to write to my mother because she'd be worrying. I could tell he'd had a few drinks, his voice trying to be light and cheerful. 'Your tea is on the table,' my mother said, and he went into the house. She got into the car and it gave a small sigh with her weight. I climbed in beside her. 'Have you got everything?' she asked me. And then I remembered my comics and ran back inside the house. Behind the kitchen door, I heard my father weeping. I was a seminarian now, on the road to priesthood and a life of prayer, study and discipline. The priest who taught us at St Richard's College, in the village of Hadzor, Worcestershire, was kind and encouraged me. I wanted to be the best student he'd ever had; he was the most beloved teacher in the seminary. We all wanted to be his friend. His voice was gentle and he listened to us with understanding and compassion. One of my classmates said one day: 'You're his favourite. That's why he has you sit in the front row, so that he can be near his pet.' One evening, when I returned to study hall from dinner, I was told to go to the priest's room, in the old part of the house. The students were rarely allowed up there – only the nuns had permission so they could clean or make the beds. Up the unfamiliar staircase I climbed – nervous, maybe I'd done something for which I would be reprimanded. In the hallway there was an odour of cigarette smoke and I could hear piano music playing from inside the room. The priest opened the door in a red dressing gown. 'That is a strange thing,' I thought, 'for a priest to be dressed like that.' Inside the room, a fire burned. The chairs were of worn leather and the shelves were full of books. I had never been in a room like that, so cosy and welcoming, unlike the cheerless dormitories we slept in. The priest bade me sit on the sofa beside him. He smelled of aftershave; a record turned on the player. 'What kind of music do you like?' he asked. At home I used to lie under the covers listening to the BBC: late-night jazz, Bill Evans, Oscar Peterson, Stan Getz. 'I love Chopin,' said the priest in his soft voice, like satin. 'He was from Poland, but he died, exiled, in Paris. Did you know that? He was an exile – like you.' He asked if I missed home. I said: 'Yes, my father and mother, and sometimes my friends.' 'I'm sure there must a girl who misses you, too.' I thought of the girl who sang in the choir, who sat beside me all the way to Portmarnock the day the altar boys went to the seaside, and how we sang together on the train coming back. We stood in the swaying corridor and our bodies touched and she didn't pull away, and I thought that meant she loved me. But I didn't want to tell the priest this, because he would think it wasn't what a boy studying to be a priest should be thinking. It was so hot in the room, and I was beginning to sweat. I avoided looking at the priest's leg, white and hairy, when he stood to change the record. 'And do you think about girls?' he asked. 'It's not a sin if you do. It's natural. You see, the female is put on the earth to be the spiritual and sexual companion of man in marriage. But we have taken a vow of celibacy, which means we forgo the physical pleasures of the body. 'Tell me, do you know what procreation is?' It was a word I had never heard before. My tongue felt like a worm in my mouth because I didn't want to answer and disappoint him. He told me it came from Latin. 'When a man and a woman lie together, it means they make love,' he said. 'That's how we all came to be here on Earth. 'Your father and mother made love and you were born, and they did that through the pleasure of sex. 'When people do this,' he continued, 'they touch each other, and they become excited in a sexual way.' I looked at the priest but I did not know what to say. I felt like my face was aflame. He asked me whether this had ever happened to me, this becoming excited in a sexual way. 'Maybe when you think about a girl you like? Or even a boy? Tell me – have you ever kissed a girl?' The priest's breath was sour and hot as he moved toward me. Then there was blackness. Even years later it feels like the night has been concreted over. I've been picking at it with a pin ever since, afraid to use a jack-hammer, afraid of what's buried in there. I looked up a photograph of him on the internet; he was with missionaries, somewhere tropical. He smiled at the camera, his arms around two boys. They were smiling, too. He had no priest's collar on, just a blue, open-necked denim shirt. His hair was long and grey. He didn't look like himself at all. For so long I blamed myself. Ashamed and guilty that I had done something wrong. There was a tear in the side of my trousers from where I'd been rough-housing in the gym. When he put his hand into the tear, I was mortified that he'd know I was wearing football shorts instead of underwear. It was because I was so good in class, studying so hard to please him, wasn't it? I wanted the praise of his gentle voice. I thought this as I lay in bed after what happened, wide awake in the sleeping dormitory. I was baffled. Yes, baffled, that was the feeling, yet it was him, so it must have been all right. Mostly I was relieved when he didn't say anything about my football shorts beneath my torn trousers. At night in the seminary, I used to look from the dormitory windows out to the motorway in the distance. As I lay awake in my thin bed, the seeds of doubt were growing about this vocation to be a priest. Hell was losing its power to frighten me, and Heaven its ability to comfort. I no longer found meaning in the chapel hymns and prayers, though I still loved the words and melodies. I imagined other lives beyond this suffocating place. During our free hour before class, a few mates and I would sneak out to the graveyard to smoke. We would talk about sex and music and football and the outside world. I was longing for a new life. How much longer could I endure the dawn bell rudely awakening the sleeping dormitories, the priest walking among the beds, prodding us into life? Days of routine prescribed by bells and study and prayers. Some of us were afraid to leave because of shame – that we would be regarded as failures or disappointments to our families, especially our mothers who believed that a priest in the house is a gift from God. But I'd had enough of being told what to think, which books I could read, what I could watch and listen to, and of being spied upon day and night. One day, a notice appeared on the board outside the breakfast room. A theatre troupe was coming to present a play, and for weeks it was all the fellows talked about. At Christmas and feast days, we had put on our own concerts and musicals, but this would be a real play with real actors from the outside world. On the night of the performance, the curtain opened to reveal the London flat of the hero, where men with moustaches and monocles were discussing a murder in clipped accents. It felt as though I was watching a dream. There was a stillness inside me as if I were under a spell. An actress entered dressed in a gabardine coat over pale legs, her hair lustrous in the surreal light of the stage. In the play she was called Marjorie. We all leaned toward her to be nearer. I could not take my eyes from her. At the end, the actors bowed and she stepped forward toward us, touching her thighs with her hands. Later, I opened the window to watch the actors board their bus. I saw her move along the pathway, dressed now in skirt and beret. Did she turn toward me and blow a kiss? Yes, she did. Not to all the fellows hanging from the dormitory windows wolf-whistling and waving, calling to her. No, it was to me, to me alone. Now I knew what I wanted to be. And what I didn't want to be. Soon afterwards I was told to pack my bags. The seminary had been monitoring me for months: my breaking of rules, my disrespect for authority. A taxi from the village came to bring me to the train. I took a last look at the great house with its flaking paint which had been my home for four years. All my newborn life was before me. In 2002, standing in my living room in New York, I lifted the phone and asked for the priest. 'Who may I say is calling?' 'An old pupil of his.' 'Let me see if he is available. He might be sleeping.' The clunk of the phone being put down. Heels across a floor. The sound of a door opening, swinging back again. Silence. Then footsteps across the floor, the phone lifted. 'Hello?' he said, as if asking a question. My mouth was dry. A hard swallow. 'You probably don't remember me. You used to teach me.' 'Oh.' His voice: smooth as satin still, and curious. I told him the year. The class number. 'Mmm,' he said. 'That's a long time ago. My memory isn't what it used to be, I regret to say.' 'I used to sit in the front row. I was from Dublin. I was very good at Latin. You said I was the best student you ever had.' 'Oh. And what is your name again?' 'You don't remember me?' 'No,' he said. I felt him smile politely. 'I'm sorry…' 'I've never forgotten you. Ever.' His voice. As warm, as charming and seductive as it had been all those years ago, as if no time had passed. 'Well, that is nice when a student calls to say a nice thing.' I couldn't think of anything else to say. My anger faltered and stumbled. There was another silence. 'Are you still there?' he asked. 'I'm still here.' 'It was nice to talk with you. I must go. The bell is ringing for benediction. I mustn't be late. It is so kind of you to call.' I wanted in those last seconds to call him a terrible word and say that even though I don't believe in Hell, I hope he does, because I want him to be terrified and burn for ever. But I said nothing. Some part of me did not want to hurt an old man with a kindly voice stuck in a retirement home who now had no memory of me or of anything he'd done. Even now I can't help but imagine how different my life could have been had I remained on my once chosen path to the priesthood. My first TV role was in a national soap opera called The Riordans, as a kind of Irish Heathcliff. The programme had already been running for many years at a time when Ireland was a one-channel land and the country came to a standstill for the show. I watched my first episode with my family. There was complete silence. Even during the commercials, none of us knew what to say. When it was over my father spoke. 'Isn't television a wonderful thing? There you are,' he said, pointing at the television. 'And there you are,' he said, pointing to me in the chair. One of the perks of being on the telly was that we were invited to open supermarkets, judge beauty competitions and the like. One of the other actors in the show advised me to invest in a white suit for these occasions, to add a touch of glamour. 'The punters expect a bit of glitz,' he assured me. During one of these events, a charity walk in the countryside, the heavens opened and we all repaired to the pub. I bought a round for everyone. A singsong started up. Several hours later I stumbled into the street and found no trace of the driver who was to return me in my sodden white suit to Dublin. A timid adolescent approached. He asked me about the life of an actor, and did I have to study for a long time. He was dreaming of becoming an actor, too, and wanted to know how I knew I was one. I told him that years ago I saw the travelling players perform in the seminary, and I just knew watching them that's what I wanted to be. 'Follow your heart. If acting is what you want to do, nothing will stop you,' I said. He told me that he had cycled the seven miles there and back to his house just to meet me. I often remember that stage-struck kid and think, that could have been me.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.