|

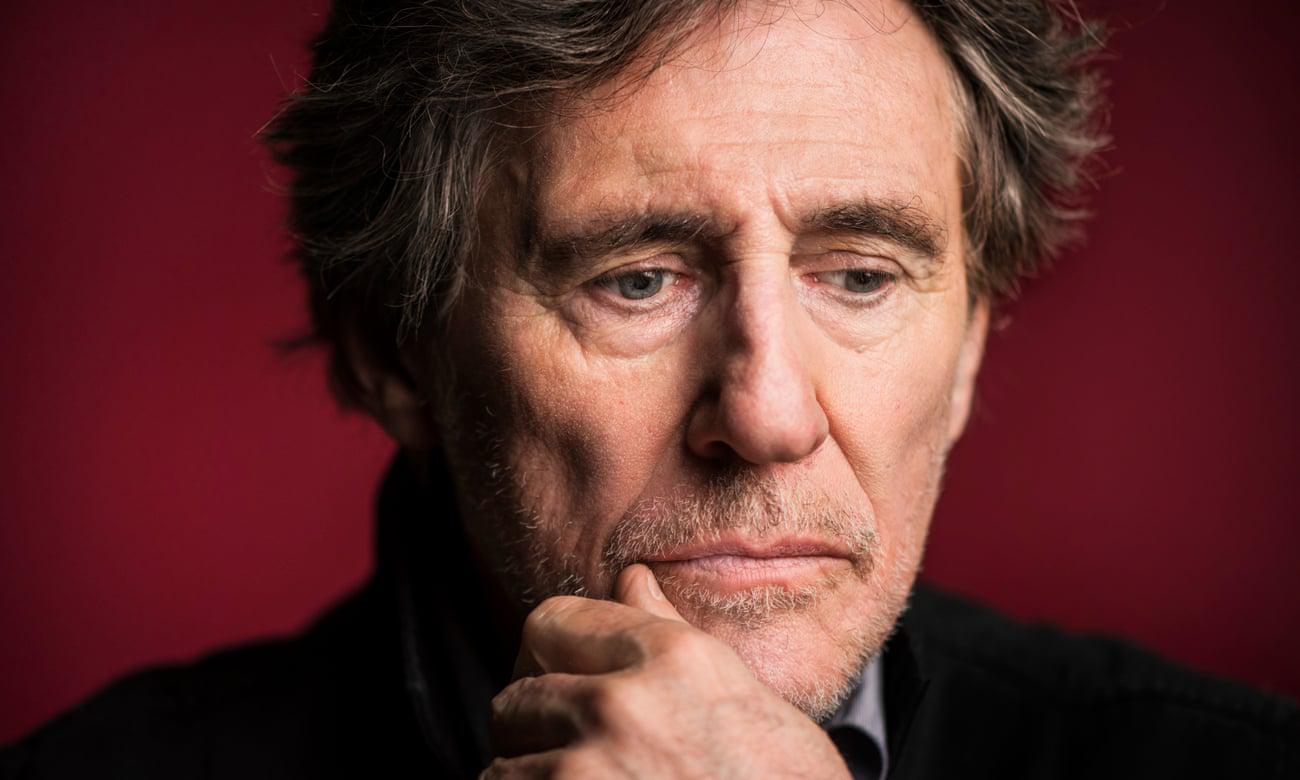

Gabriel Byrne: 'There’s a shame about men speaking out. A sense that if you were abused, it was your fault'

By Catherine Shoard

The actor’s autobiography confronts the abuse he experienced at the hands of the church. But he has just as much contempt for Hollywood – and US presidents from Obama to Trump Forget the pollsters. If you wanted to know the outcome of last week’s US election, you just had to ask Gabriel Byrne. I did, a month ago. I wish I had gone to the bookies. Byrne was in London on the way back to his farm in Maine, where he lives with his wife and three-year-old daughter. It’ll be thin, he said, Biden’s margin is miles slimmer than anyone predicts. He called it in 2016, too. “If you were in touch with the rage that was on the ground, you were not looking at Hillary Clinton and saying, she’s going to get elected. That rage is still on the ground. The 40 million who support Trump haven’t wavered one iota.” When he emails on Thursday night, he blames the Democrats for the tight result. “This is the second time they’ve come up against a gameshow host and they’ve learned nothing. Again they seriously underestimated the level of anger among mostly blue-collar workers.” I don’t need to ask if he feels any optimism; he has already been pretty clear. “At least it’s the end of that guy but, personally, I can’t stand Biden. An exceptionalist roaring about America as the moral leader of the world, all this crap. You can’t appeal to people in Maine or Wisconsin or Michigan by saying this is a battle for the soul of America. It’s just political garbage. “Nothing much will change under Biden because his thing is: let’s return America to what it was. Well, what America was caused Trump. The Democrats rolled out the red carpet.” Obama’s record stinks, Byrne says. Neither is he keen on the Clintons. The last leader he respected? There is a long pause. “Martin Luther King.” He goes on. Reagan “should have served jail time”. “Since 1945, the US has embarked on 75 different military interventions toppling legitimate regimes. And yet the big thing is that Russia interfered in the American election? The Americans have interfered in every election around the world.” In writing, Byrne sounds splenetic. Folded on a sofa, he is as mild and smiley as a tortoise. He reminds me of the poet and critic Tom Paulin: not just the accent (different parts of Ireland, I know) but the benign contrarianism – forever gentle, no matter how firecracker the take or how close he skips to conspiracy theory. He seems genuinely affable, unlike his characters, whose geniality usually has definite threat glinting beneath. This uncertainty has long been key to Byrne’s appeal, likewise that stupid beauty, smudged a little now he is 70. Yet Byrne does not carry himself with the confidence you expect from a veteran smoulderer. He nods, a bit awkwardly. Catholic shame and “male teenage [body] dysmorphia” kicked vanity out of him young, he says – literally, when a priest clobbered him for looking in the mirror. “If you’re brought up in that world, you never get to the stage of thinking it’ll be easy with women.” Point taken, if slightly undermined by his friend Liam Neeson, who emails to say that Byrne “personifies the ‘dark brooding Irishman’” (the middle word is one he has long gone on record about hating). “The ladies all think he’s the bollix,” adds Neeson, “and they’d be right!” Anyway, Byrne is today very much channelling the history teacher he was for about eight years. Neeson says: “He has an acute intelligence and remarkable insight into the human condition. He can also be very funny.” And, actually, after three hours with him, that feels pretty fair. Byrne is bright and gabby and friendly and professorial. He has a lot he wants to say, about the abuse of power, about why ordinary people stand for it, and about how much the movies are responsible. Forty years as an actor and 30 as a movie star – Arthurian fantasy Excalibur (1981) was his first film, the Coen brothers’ Miller’s Crossing (1990) his best, The Usual Suspects (1995) the last for which he had to audition – have left him with no illusions about Hollywood’s influence. He is evangelical that we recognise “the power of film to form you. It’s not just an escape and not just entertainment, it’s influencing the way you see the world.” When I ask if he feels culpable, he grins with almost masochistic enthusiasm. He says he has tried to take on only those projects he thinks have something valuable to say – Louder Than Bombs (about grief), Hereditary (family secrets), Lies We Tell (a drama directed by a window-fitter, which he agreed to “because I’ve never seen a movie about Muslims in Bradford”). But, yes, he feels guilty that he is in the pay of a bad business. “Hollywood isn’t interested in making artistic statements or necessarily even entertaining. It’s interested in making money. That’s its first and only goal. It doesn’t have a conscience.” An ideal tool, therefore. “When I found out that the Pentagon has a film department, a lot of things made sense to me. America reveals itself to the world through film. We absorb the American dream because they own the means of production.” Politicians twigged this yonks ago, of course. “Reagan and Bush essentially appealed to American cinema mythology; the good guys out on their farms in cowboy hats. America is Gary Cooper. The terrorists are the Indians on horseback. Trump appeals as much to our cinematic language as to our politics: he works through the old reliables of fear and lies.” Our ability to distinguish truth from fiction is in desperate peril, Byrne thinks, “and that’s where they want us”. He frets about how Zoom is fast-tracking a breakdown in human relations, and has just read a book about terrifying advances in sex-doll technology. “We now prefer the fantasy,” he says. “We find comfort in the lies. I was the victim of that for so long. I imbibed everything. It led to a place where I became extremely unhappy. And now I question everything. I believe it’s a responsibility to do it.” That is why he has written that weirdest of things: a plain-speaking celebrity memoir. Well, almost. Walking With Ghosts is lavish with lyricism, but presents a pretty unvarnished version of its author. Byrne uses its pages to ask forgiveness from those long gone (his parents, his sister) and missing in action (a teenage friend he lied about sleeping with; a bullied schoolboy dunked in a lake). He says of the friend: “I betrayed her so that I could look like a big, tough guy. I don’t know where she is but felt it right to say, please forgive me. And when that kid was thrown into that pool, I will never forget his face. We all have people to whom we need to say, listen, I didn’t know what the hell I was doing.” Yet the book’s most memorable section is not a mea culpa, but a reckoning with the Catholic church: testimony to why he can never forgive the institution that dominated his childhood – and, perhaps, everything since. Byrne grew up in Walkinstown, Dublin, about six miles from the city centre, and remembers feeling a constant, crippling terror, not exclusively caused by the cold war. “The pandemic is: if you keep your mask on and obey the rules, we will get through. Nuclear war meant that by next Wednesday we’d all be dead, fried in our houses,” he says. “It determined a great deal of how you thought about the world, because Catholicism thrives on fear.” On the weekend, he would see 12 films (“get some chips and go back in”) to shore up an alternative reality to that outside the cinema doors. “School was utterly terrifying. It was not a safe place for children.” Byrne was sexually abused by priests from the age of eight; then, three years later, dispatched to a seminary in England where, lost and homesick, he found comfort in the attentions of an encouraging teacher. “What I remember most about him was his voice. It was very beguiling and calming,” he says. In his book, Byrne records the evening he was first invited to the man’s room. “I’d never seen it written down before – how you reel in an 11-year-old. Saying, ‘Oh you must be missing a little girl or maybe a little boy?’ Saying, ‘Are you this way? Are you that way?’ Having laid the ground in the most sophisticated way by saying, ‘You’re great at that. You’re terrific.’” It is horrific reading. “The priest’s breath was sour and hot as he moved towards me,” Byrne writes. “Then there was blackness.” This was not an isolated incident. “I remembered every single moment up to a point,” he says today. “Then it’s concreted over. What’s buried there? Is it something worth exhuming?” Evidently he felt it was worth putting on display. “Yes. Maybe if I say it, it will lose its power over me.” I can’t imagine he holds out much hope; Byrne forever circles the crime. If he does this in conversation, imagine what it is like in his consciousness. A few years ago, he found a photo of the priest online with his arm around two 14-year-olds, on missionary work, somewhere tropical. More recently, he rang him in his retirement home. “All that time later I was shocked by how his voice was so seductive.” Byrne asked if the man remembered him. He said no, which Byrne believes. He left it at that. The priest has since died. When he found out how widespread the abuse was in his own schools, and beyond, Byrne was both horrified and relieved. “For many years, I really thought I was the only one. The freedom it gave me to be able to say: ‘Me, too. I was assaulted, too.’” Yet so little action has been taken. “There’s a kind of an unspoken acceptance of the idea that sex against girls is kind of the real assault. The violation of women is what you should pay attention to. There’s a shame about men speaking out. A sense that if you were abused, it was your own fault. Men are not supposed to talk about their feelings. Men have to be strong and men don’t cry.” Just as he blames the Democrats for Trump, so he saves his anger not for the priest, but his protectors, who moved him around – perhaps, even, pushed him into a corner. “It’s supposed to be a church of love and yet to deny his love to its priests? It’s incomprehensible that you would say to a man or a woman: ‘You can’t have a partner. You can’t be in love with anybody.’” For Byrne, liberal indulgence of Pope Francis is as perverse as the deification of Obama. “He’s done absolutely nothing to address the real issues of child sexual abuse or the role of women or divorce or birth control.” Did he ever think he might? “It’s a corporation and the CEO can’t turn it around. And they’d never elect someone unless their thinking was known.” Byrne can seem defeatist. He isn’t. “It still makes me angry. The church still controls education in Ireland. And it’s an obscenity to tell innocent children they’re going to go to hell for taking sixpence out of their mother’s purse.” As well as a three-year-old daughter, Byrne has two other children: Jack, 31, and Romy, 28, from his marriage to Ellen Barkin, for whom he first moved to the US. For a while, they were one of film’s most endearing power couples: larky, slightly dishevelled, married in Las Vegas. They separated amicably in 1993 and Byrne stayed in New York. He has been with his second wife, Hannah Beth King, 45, an American film producer, for about eight years. The US state education system also left him unimpressed and suspicious. “It’s regarded as important not to put money into it, because if you put money into it, you start people thinking, and then they start to question the system and that’s dangerous.” For his youngest, he might try something else. “I want to go on that journey with my child trying to expand their vision of the world. I’m not going to leave it to them to take over her brain.” He does not want to talk on the record about his second daughter but you can’t imagine he would have written Walking With Ghosts without her being around. It is a peculiar book – half morbid, half a determined attempt at rebirth. “If you lose your curiosity about the world,” he says, “you’re in danger of, in some small way, kind of dying.” He’s awestruck by how long a small child can look at a leaf. “I want what they have!” The book is also a conscious departure: stylistically ambitious, purposefully (and successfully) so. “Yes, yes, yes. I wanted to write it.” He cares about the reviews – even if you don’t read them, he says, you always get the gist. “People come up and say: ‘Listen, I just want you to know, I did not agree at all with what they said in the Guardian.’” Now, he is 80-odd pages into his first novel, set among Irish construction workers who built roads and railways tracks and the M4. It’s a love story about home, too. He sounds in no hurry to return to movies. Shooting the second season of Fox’s War of the Worlds in Wales this summer doesn’t sound a lot of fun, with the morning Covid swabs and “subliminal atmosphere of fear”. Seven years on the west coast left him unsmitten. “One of the most depressing journeys I think you can make is to go across the canyons in LA, down to where the studios are.” He never got used to going to parties where the likes of Michael Douglas would open the door. “It’s a ridiculous place to want to be accepted. Like going into a hardware store and looking for a pizza.” His reaction to the industry today verges on repulsion. “The oil that keeps the factory moving is bullshit,” he says. “Whether you were at that table or not at that table is irrelevant. The bullshit will continue and it’ll be somebody else doing it.” Might he return to Ireland? He can’t, he says: an immigrant thing, too much water under the bridge. But he is still there in his head, anyway. The other night he dreamed of being a bus conductor, hanging off the bar at the back (incidentally, it was being on a bus, following two miniskirted girls upstairs to the top deck, aged 15, that made him realise he wasn’t cut out for the clergy). For all his criticism of the church, he defends his homeland at every opportunity. The people there are real heroes, not your “fake mythological movie” versions. His brother was an ambulance driver for 34 years – and a fireman. He reels off other examples: “Taking care of your mother when she had Alzheimer’s – that’s heroic. Bringing up three kids with no husband. Struggling on after your wife died.” He is especially fired up calling out myths surrounding Ireland’s supposed drinking problem. “The notion it’s a cultural characteristic and a moral failing has been used as propaganda by politicians to put Irish people down. France has a huge alcohol problem. It’s a myth all French women are thin and look amazing at 90 and eat chocolates for breakfast and smoke 100 cigarettes. “Britain has a gigantic problem. The notion of getting pissed three times a week is so culturally enmeshed. Life centres on the pubs. They’re on every corner. It’s absolutely shocking, seeing people drunk in the street. And it’s not just addiction to alcohol and drugs, but to materialism, shopping, television, anything that takes you out of reality.” As for Byrne, he is now 23 years sober and “wild horses wouldn’t get me into a bar these days”. That is easy in the US – especially back on the farm, with the toddler and the chickens. If he ever touches substances again, he says, it will be right at the end – he wants to go out like Aldous Huxley, who took LSD for the first time on his deathbed. “I just don’t want to be hit on the head with a brick.” At least it would be quick, I say. “It might be. You might be lying there saying, ‘Fuck, I just got hit on the head with a brick and I’ve no LSD with me.’”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.