|

Irish leader apologizes for cruelty to unwed mothers and babies at homes run by the state and Catholic Church

By William Booth And Karla Adam

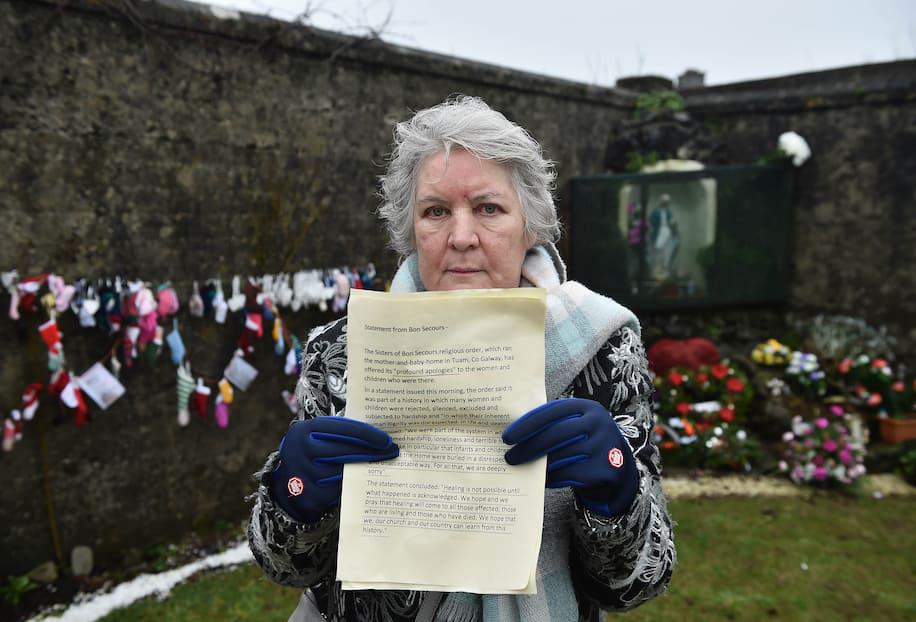

In a signal moment, to mark Ireland's "dark, difficult and shameful" treatment of unmarried women and their babies over the 20th century, the republic's prime minister, Micheál Martin, rose in the Parliament in Dublin on Wednesday and formally apologized for the state's complicity in "a profound failure of empathy, understanding and basic humanity." Martin spoke after the long-awaited release of a 3,000-page report from the Commission on Mother and Baby Homes, which investigated conditions for the 56,000 unmarried mothers and 57,000 children who passed through the system — at 18 homes run by the state and by Catholic charities — from 1920 until 1998, when the last facility was shuttered. The unmarried mothers, often destitute, desperate and young, with nowhere else to turn, sought last-ditch refuge in the homes or were shoved into them, having been cast out by their families. Infant mortality at the institutions was in many years double the national average. Some 9,000 infants died — 15 percent of all those who were born in the system — a statistic the investigators call “appalling.” Most of the babies who survived were offered up for adoption, including in the United States, often without full consent by the mothers. Martin said: “We treated women exceptionally badly. We treated children exceptionally badly.” The Irish leader said his society had suffered from a “warped attitude to sexuality and intimacy,” with a “very striking absence of kindness.” “We honored piety but failed to show even basic kindness to those who needed it most,” he said. New details of what happened to the women and their babies still have the ability to shock — though testimonies, novels, films and news reports have told of the homes for years. The release of the report has dominated the conversation in Ireland, even as the country faces the world’s highest rate of coronavirus infections. The Irish Times called the findings a condemnation of Irish society in past days, “its rigid rules and conventions about sexual matters, its savage intolerance, its harsh judgmentalism, its un-Christian cruelty.” The impetus for the report came from the discovery of infant remains at the Bon Secours Sisters home in Tuam, western Ireland. Dogged historians discovered death certificates for almost 800 infants at the home but could not find burial records, until the grim excavations began. While much blame has been directed at the Catholic Church and its religious orders, the report stresses that the some of the homes with the most wretched conditions were operated by the local health authorities. In his remarks in Parliament, Martin highlighted extracts: “I was treated like a second-class citizen by my family. Society had an obsession with hiding everything,” one witness said. “Nobody will want you now,” said the mother of a witness, pregnant at 14. “Get her put away!” were the words of a father of a 19-year old when told of her pregnancy. Survivors of the homes have been telling their stories on Irish television, too. Terri Harrison went to London when she discovered she was pregnant, only to be tracked down by a priest and nuns, who brought her back to Ireland and placed her in a mother and baby home. It was 1973, and Harrison was 18 at the time. “They dehumanized and distanced us but kept reminding us how dirty and filthy we were,” she said. Her son was put in a locked nursery, and she was allowed to see him only at feeding times. And then one day her son was gone. “I fed him at 6 a.m. That was the first feed on the Saturday morning. He would have been five weeks old. I went up, and his cot was empty,” she said. Harrison said: “They threatened me with the high courts. They were going to ring my father in his place of work. They were going to put me in the national newspapers, and under no circumstances would I ever be allowed to take my son back because he was happy with his Mommy and Daddy.” “I couldn’t fight them, I didn’t have the tools,” she said. The authors of the report note that the experience of women and children in the 1920s was vastly different than in the 1990s. In the early years, Ireland was an impoverished country, among the poorest in Europe, and life was hard for many, and the homes for unmarried mothers were run like workhouses. In later years, there was schooling, counseling and more services. But the report notes that for the unmarried mothers, Ireland wasn’t just poor, but “a cold harsh environment.” The investigation found that greatest number of admissions was in the 1960s and early 1970s: “The proportion of Irish unmarried mothers who were admitted to mother and baby homes or county homes in the twentieth century was probably the highest in the world.” The report makes for hard reading: “Many of the women did suffer emotional abuse and were often subject to denigration and derogatory remarks. It appears that there was little kindness shown to them and this was particularly the case when they were giving birth.” The Sisters of Bon Secours, a Catholic religious order, which ran the mother-and-baby-home in Tuam, offered its “profound apologies” in a statement Wednesday. The order wrote: “We were part of the system in which they suffered hardship, loneliness and terrible hurt. We acknowledge in particular that infants and children who died at the Home were buried in a disrespectful and unacceptable way. For all that, we are deeply sorry.” Colm O’Gorman, executive director of Amnesty International Ireland, said the report “absolutely validates” the testimony of many survivors and victims over the years who talked about forced labor, appalling acts of abuse and forced adoptions. “Adoption without freedom of consent is not consensual adoption. I don’t know how else it can possibly be described,” he told The Washington Post. “These should have been the safest places for children to be born; instead, they were the most dangerous places,” he said. O’Gorman said that while the church had apologized, “we’ve yet to see the church fully acknowledge the degree to which it created and enforced the culture,” rather than saying it was merely “part of a culture.” He said it was a mistake to focus “on the role of society, as opposed to the role of the Catholic Church and of the state. As if somehow people were free to oppose that dogma and norms of the time. . . . The reality is that up until relatively recently, Ireland was effectively a theocracy.” In Ireland, the once dominant Catholic Church shared power with the government, overseeing daily lives, running schools, hospitals, nursing homes, social welfare and poverty programs. But in recent years, the Irish have steadily rejected directives from the church, overturning constitutional prohibitions against divorce, birth control, same-sex marriage and abortion. “If the church is to be fully honest, it needs to acknowledge that it wasn’t simply somehow an equal partner in all of this,” O’Gorman said, but rather “it directed and dominated a culture that stigmatized women, that violated the rights of women and children, that brutalized people in this country and hundreds of thousands of women in particular.” The Irish prime minister vowed to act on all the recommendations of the report, including a restorative justice program, and to deliver the legislative change necessary to “at least start to heal the wounds that endure.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.