Lawyers Question S.F. Archbishop's Role in Molest Cases

By Don Lattin

San Francisco Chronicle

July 10, 2004

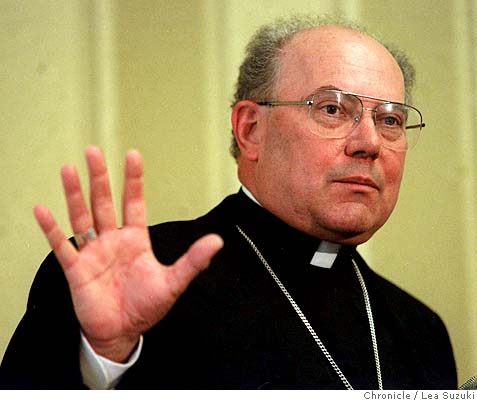

Two lawyers representing Oregon molestation victims have raised questions about the role San Francisco Archbishop William Levada played in a priestly sex abuse scandal that led to this week's unprecedented bankruptcy of the Archdiocese of Portland.

Levada, who served as the archbishop of Portland from 1986 to 1995, oversaw church disciplinary proceedings against two Oregon priests accused of child molestation, including one who was put back in regular parish ministry in 1994, following a brief period of "rehabilitation," the attorneys say.

On Tuesday, the Portland Archdiocese -- which has spent more than $53 million to settle more than 130 claims of priest abuse -- became the first Catholic diocese in the nation to file for bankruptcy.

|

| William Levada, San Francisco archbishop, was archbishop of Portland from 1986 to 1995. |

That bankruptcy filing also suspended a potentially embarrassing and costly trial against the archdiocese and the late Rev. Maurice Grammond, who has been accused of molesting dozens of boys in the Portland area. It had been scheduled to begin Tuesday.

Jeffrey Anderson, one of the lawyers suing the Portland archdiocese, said Levada "is one of a long line of bishops that has given sanctuary to Grammond -- a known predator."

"Levada inherited a secret and kept it the nine years he was there," Anderson said in an interview.

Maurice Healy, the spokesman for the Archdiocese of San Francisco, said Levada had no comment on the Portland bankruptcy.

But in a lengthy deposition given in San Francisco on April 7, Levada denied that his predecessor, the late Portland Archbishop Cornelius Power, had given him any warnings about Grammond's sexual history when Levada took over in 1986.

Church officials in Portland insist that Levada's actions did not violate church regulations or state law in place between 1986 and 1995.

But lay leaders and abuse victims in the church say Levada and his successors had a moral obligation to warn parishioners that they had accused child molesters in their midst.

"Not only Levada, but all these bishops continued to cover up (for abusing priests) into the 1990s," said Ed Gleason, the Northern California director of Voice of the Faithful, a national organization of Catholic laity. "They disregarded evidence that questioned whether these priests could really be rehabilitated."

In Portland, Catholic lay leaders say the roots of the current financial collapse go back to actions taken -- or not taken -- during the Levada years.

"We lay the financial crisis at the feet of bishops going back 30 years," said Gayle Bacsh, the co-chair of the western Oregon chapter of Voice of the Faithful. "Until we see the institutional church adopt fundamental principals of financial transparency, it will be hard for the bishops to regain the trust they have squandered."

In the Archdiocese of Portland, the costliest and most notorious pedophile priest has been Grammond, who spent 15 years at Our Lady of Victory in Seaside, Ore., and served at two orphanages and several rural parishes.

Grammond has been accused of molesting more than 50 boys from the early 1950s to the mid-1980s.

Levada said in his deposition that he remembered Grammond as "a guy who was nervous, was a hypochondriac, was unhappy where he was."

In 1988, Levada gave Grammond a medical retirement. Three years later, the archbishop said, he learned that a former altar boy had accused Grammond of molesting him.

At that time, Levada said, he told the priest "not to engage in public ministry."

That action was required because retired priests often celebrate Mass, attend parish functions and perform other church functions after retirement.

"First, I think I asked him to go for an evaluation, (but) it seemed that he was a difficult person to get a full psychological profile on," Levada said in his deposition.

Grammond died in 2002.

During his time in Portland, Archbishop Levada was also involved in the case of another priest accused of molesting two men when they were students at Central Catholic High School in the 1970s.

That priest, the Rev. Joseph Baccellieri, was accused of molestation in a lawsuit filed in February by two anonymous plaintiffs.

Their attorney, David Slader, said Levada had sent Baccellieri to a treatment program for molesters in 1992 but allowed him to return to parish ministry in 1994.

Baccellieri served at several parishes before the current Portland archbishop, John Vlazny, removed him from ministry in July of 2002.

That was right after the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops met in Dallas and adopted a "zero tolerance" policy toward priests facing credible allegations of sexually abusing minors.

Bill Crane, the Oregon director of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, said he was shocked that Levada had allowed Baccellieri back into parish ministry in 1994.

"These child molesters should have been turned over to the police," Crane said.

Crane accused the current church leadership in Portland of using the bankruptcy courts to "sidestep justice."

"The hierarchy of the Catholic Church takes the path most advantageous to itself," he said.

While sexual molestation in the Catholic Church resurfaced as a national scandal in Boston in 2002, the bishops have been getting warnings for more than two decades.

In 1982, the bishops' national staff issued the first warnings about costly lawsuits. Three years later, the bishops were given a detailed, confidential report warning that sex abuse litigation could cost the church "many millions of dollars" and "devastating injury to its image."

Ten years later, the scandal continued. In June 1992, the entire U.S. bishops conference discussed clergy sexual misconduct in sessions closed to the press and public.

In 1993, they announced the formation of an Ad Hoc Committee on Sexual Abuse, which issued a set of guidelines.

During the 1980s and 1990s, sex abuse scandals involving priests, children and teenagers erupted in dioceses across the United States and Canada -- including San Francisco, Santa Rosa and Stockton.

However, said Bud Bunce, a spokesman for the Archdiocese of Portland, church law in 1994 did not require Levada to remove Baccellieri from ministry, and the age of the victims did not require the church to turn the priest over for criminal prosecution.

"Those allegations were about abuse back in the 1970s," Bunce said. "We've had no accusations of abuse (by any priest) occurring after 1984."

The Rev. Thomas Reese, an authority on the American Catholic hierarchy, also warned against judging Levada by rules that were adopted after he left Portland to become the archbishop of San Francisco.

"It makes a big difference when a bishop did something," said Reese, the editor of America magazine, a Jesuit-run weekly. "There was total ignorance until 1984 or 1985. But after 1993, bishops that made mistakes have more explaining to do."

In his April 7 deposition, Levada was briefly asked about Baccellieri -- the priest put back into parish ministry in 1994 -- and said, "I believe there was some allegation that occurred while I was there."

But attorneys for the San Francisco archbishop objected to that line of questioning, so Levada did not elaborate.

By filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, the archdiocese halts all legal action against it and allows the federal courts to preside over a financial plan to pay off creditors while the church continues to function.

In filing its bankruptcy Tuesday, the archdiocese said it faced more than $340 million in additional claims from 20 lawsuits.

Legal experts say the action raises new questions about how much control the state can assume over the operations of the Catholic Church and exactly what church property can be used to pay off creditors -- including abuse victims. E-mail Don Lattin at dlattin@sfchronicle.com.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.