Officials gave comfort despite abuse charges

By Walter V. Robinson and Matt Carroll

Boston Globe

January 24, 2002

http://www.boston.com/globe/spotlight/abuse/stories/012402_documents.htm

This article was prepared by the Globe Spotlight Team: Editor Walter V. Robinson, senior assistant metropolitan editor Stephen Kurkjian, and reporters Matt Carroll, Sacha Pfeiffer, and Michael Rezendes. It was written by Robinson and Carroll.

[See the main page of this feature, with links to other articles in the feature and images of the original newspaper.]

Even as two successive cardinals and dozens of church officials learned of growing evidence that the Rev. John J. Geoghan could not control his compulsion to molest children, Geoghan found extraordinary comfort in his church.

In succession, Cardinals Humberto S. Medeiros and Bernard F. Law offered him their prayers, but never condemnation. Even as prosecutors closed in, Law wrote Geoghan in 1996: "Yours has been an effective life of ministry, sadly impaired by illness.... God bless you, Jack."

|

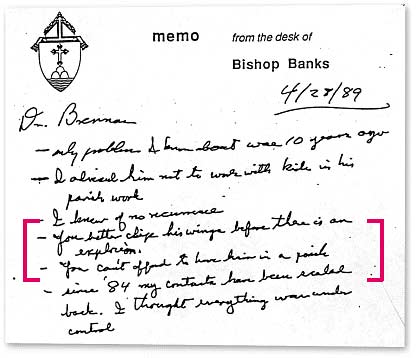

| "You better clip his wings before there is an explosion," Bishop Robert J. Banks wrote in this memo to himself, referring to the Rev. John J. Geoghan. The heading "Dr. Brennan" apparently refers to the psychiatrist who had long treated Geoghan. [See also the PDF of this Banks memo.] |

Bishop Thomas V. Daily, once the top deputy to both cardinals, likened Geoghan to a lost sheep. In dozens of internal communiques, Geoghan's superiors and his doctors regularly alluded to his pedophilia euphemistically. After Geoghan was removed from a Dorchester parish in 1984 for abusing children, Dr. Robert W. Mullins called the episode "a rather unfortunate traumatic experience" -- for Geoghan, not the children. [See the Mullins letter.]

In dozens of internal communications, obtained by the Globe under court order over the objections of the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston, bishops and cardinals almost never mentioned that Geoghan had victims, although more than 130 people have since come forward charging they were abused. Their focus, instead, was on righting Geoghan and sending him on to another parish.

At times, the concern for Geoghan suggested by the documents turned to outright coddling. For instance, Geoghan was sent to Rome for a two-month sabbatical just after relatives of Geoghan victims met with Daily in August 1982 to demand that he be removed from the ministry.

And in 1989, according to his own notes, Bishop Robert J. Banks was told by a psychiatrist who had treated Geoghan: "You better clip his wings before there is an explosion. ... You can't afford to have him in a parish." [See Banks memo.]

Yet a year later, Geoghan asked Law to promote him to pastor of St. Julia Parish in Weston. Even Banks said he would recommend that Geoghan become a pastor at some time.

|

| [See a web page of these excerpts from Gallant's letter, with links to a complete transcript and to PDFs of Gallant's handwritten letter and Cardinal Medeiros's reply. |

Law picked someone else. But the Rev. Kevin J. Deeley, the church official who relayed the bad news, encouraged Geoghan to apply for another position as pastor. [See Deeley letter.]

At the time, Geoghan had been removed from four straight parishes between 1974 and 1989 for molesting children. In 1989, with approval from Banks and Law, Geoghan was returned to St. Julia's in Weston, where he resumed working with altar boys.

Geoghan's favorable treatment by church officials is outlined in thousands of pages of church documents and transcripts of depositions of church officials collected by lawyers in 84 civil lawsuits against Geoghan, the archdiocese, Law, and several other bishops. The archdiocese has already paid more than $10 million to settle suits by about 50 other victims. Last week, Geoghan was convicted of molesting a Waltham boy more than a decade ago. He faces two more criminal trials in Suffolk County.

Mitchell Garabedian, the lawyer who represents almost all the plaintiffs against Geoghan, said in an interview last night that the documents prove that the archdiocese acted irresponsibly in its handling of Geoghan. Even during Geoghan's years in the seminary, there were clear signs that he would become a problem priest, Garabedian said of the documents.

The documents had been under a court-mandated confidentiality order for more than a year. But acting on a motion by the Globe, Superior Court Judge Constance M. Sweeney, who is presiding over the civil lawsuits, overturned the order in November. An appeal to the state Appeals Court by the archdiocese was denied.

Donna M. Morrissey, the spokeswoman for the archdiocese, did not return telephone calls from the Globe yesterday seeking comment on the documents.

On Jan. 9, Law apologized to Geoghan's victims and for his own oversight of Geoghan after Law became archbishop of Boston in 1984. "In retrospect," Law said, his judgments about Geoghan had been "tragically incorrect." [See Law's apology.]

Law's apology followed publication of a two-part Globe Spotlight series reported that Law and other church officials had shuttled Geoghan from one parish to another, even though they knew of his sexual abuse of children. [See the two-part series.]

But what is striking about the documents that became public this week is the indifference of the church to the extent of Geoghan's abuse. With just one exception, the Geoghan records and the transcripts of depositions of church officials contain no hint that anyone around the cardinal urged him to remove children from Geoghan's reach until 1993.

That exception, the Globe reported on Jan. 6, occurred after Law sent Geoghan to the Weston parish in 1984. Three weeks later, Bishop John M. D'Arcy challenged the wisdom of the move in a letter to Law, saying he was worried that Geoghan might cause further scandal. [See the D'Arcy letter.]

But if other bishops expressed similar concerns, it is not reflected in the documents. Daily, now the bishop of the Brooklyn diocese, acknowledged in his deposition that fear of public exposure was one of the reasons for the way Geoghan was handled.

Daily, who was for a time the top deputy to Medeiros and then Law, was asked about the words "public perception" in his notes.

Q. What does that mean?

A. I don't know. It might well have referred to the thought of scandal, if it became public, this whole thing -- I don't know. Public perception. In other words, I am underlining that because of the concern of the public reaction.

Q. Was it a policy in the archdiocese when you were in Boston to avoid scandal where possible?

A. Yes.

Q. And were these events types of events that would cause scandal for the church?

A. Yes.

That is why, Daily went on to explain, he urged the relatives of seven Jamaica Plain victims of Geoghan, all from the same extended family, to keep quiet about the abuse.

One of those relatives wrote to Medeiros after that meeting, complaining that Daily had suggested "that we keep silent to protect the boys -- that is absurd since minors are protected under law, and I do not wish to hear that remark again, since it is insulting to our intelligence." [See Gallant's letter.]

Medeiros, in his Aug. 20, 1982, reply to the relative, which was contained in the documents made public this week, called the incidents of abuse "a very delicate situation and one that has caused great scandal."

But the cardinal wrote that, "I must at the same time invoke the mercy of God and share in that mercy in the knowledge that God forgives sins and that sinners indeed can be forgiven." [See Medeiros's reply.]

Two years later, after Law had removed Geoghan from St. Brendan Parish in Dorchester for abusing other children, Margaret Gallant wrote to the new archbishop to report that Geoghan had just recently been seen with many young boys and to urge Law to act against Geoghan.

"Our family is deeply rooted in the Church with a firm love for Holy Orders," she wrote. "We do not accuse this priest of sin, since we are all sinners, but rather we speak here of crime." [See Gallant's letter.]

The records do not contain any evidence that Law replied to Gallant. Two months later, Geoghan was sent to St. Julia Parish in Weston.

St. Julia's parishioners were unaware of Geoghan's pedophilia. And his new pastor, Monsignor Francis S. Rossiter, assigned Geoghan to oversee the altar boys and two other youth groups, even though Rossiter had been made aware of Geoghan's past, according to the newly public church documents.

But last April, when Rossiter was questioned under oath about his knowledge, he was evasive, suggesting he wasn't told much at all.

Q. And you were told what some of his prior problems were, weren't you?

A. No. I would say no specifics were provided. Just a letter that said he was assigned.

Asked again whether he knew about Geoghan's problems when he arrived at the parish in 1984, Rossiter replied: "I really can't say."

But by then, according to the documents, Geoghan had been removed from three parishes for molesting children: St. Paul's in Hingham in 1974, St. Andrew's in Jamaica Plain in 1980, and St. Brendan's in Dorchester in 1984.

|

| Cardinal Bernard V. Law discussing sex scandals involving the Catholic Church earlier this month at his residence. Globe staff file photo / David L. Ryan. |

The records show that archdiocesan officials were well aware of Geoghan's problems. And so were many priests, according to a deposition by the Rev. William C. Francis. After Geoghan's removal from St. Brendan's in 1984, among priests "there was talk that he had been fooling around with kids," Francis said.

Two weeks ago, the Globe reported that a former priest who served with Geoghan in the 1960s at his first parish, Blessed Sacrament in Saugus, complained that Geoghan brought boys to his room at the rectory.

The new depositions include testimony from several priests that Geoghan had altar boys in his rectory rooms during his seven-month assignment at St. Bernard's in Concord in 1966 and 1967 and again during his abuse-ridden stay at St. Andrew's from 1974 to 1980. That assignment ended when Geoghan admitted abusing the seven boys who were related to Gallant.

At St. Andrew's, according to a deposition by Geoghan's pastor there, the Rev. Francis H. Delaney, the housekeeper told him "that Father Geoghan had some urchins up there letting them use the shower, so I confronted him on that and said, `You know the rule,' and he denied it vehemently, but I had no proof."

All along, archdiocesan officials relied primarily on two Boston doctors, Robert W. Mullins, a general practitioner; and John H. Brennan, a psychiatrist, to treat Geoghan.

But the Globe reported last week that while Mullins is listed as providing Geoghan with psychotherapy, he has acknowledged to the Globe that he has no background in that specialty. Brennan had no other experience treating sex offenders, and two of his female patients sued him, accusing him of molesting them. Brennan settled one of the suits for $100,000. In the other case, a jury found for Brennan after a civil trial.

Geoghan, in a 1980 letter to Medeiros after he was removed from St. Andrew's, told the cardinal that he was receiving "excellent care" from "two wonderful Catholic physicians," referring to Mullins and Brennan. [See Geoghan letter.]

Both doctors also reported to the archdiocese in December 1984 that Geoghan was fit for the Weston assignment. [See letters from Mullins and Brennan.

But in 1989, when Geoghan was hospitalized at the Institute of Living in Hartford, the psychiatrist who treated him for pedophilia was dismissive of Mullins's earlier treatment, according to the documents.

"The patient had been seeing an internist for his psychotherapist, which was more along the line of friendly paternal chats and not really psychotherapy," Dr. Robert F. Swords wrote to Banks. Mullins has been the Geoghan family physician for more than 40 years.

The role of Banks in overseeing Geoghan is contradictory, according to the documents. It was Banks who was warned by Brennan in April 1989 that Geoghan might explode. That prompted Law to take the priest out of St. Julia's and place him in two treatment facilities over a six-month period. Banks, who had just fielded fresh complaints of abuse against Geoghan, asked him to resign, according to church documents.

Yet six months later, Banks was so unhappy with a psychiatric report from Swords describing Geoghan as a pedophile in remission that Banks sought -- and received -- a more favorable diagnosis, according to the documents.

Subsequently, Banks, who is now bishop of the Diocese of Green Bay, Wis., registered his opinion that Geoghan was fit to be a pastor. Earlier this month, Banks declined to discuss his handling of Geoghan with the Globe.

If Law ignored obvious, ominous signs about Geoghan starting in 1984, the documents provide the first evidence that as early as the 1950s, Geoghan's superiors wanted him to resign from Cardinal O'Connell Seminary in Jamaica Plain.

The documents also show for the first time the intervention of his uncle, Monsignor Mark H. Keohane.

In July 1954, the Rev. John J. Murray, the seminary rector, wrote to the Rev. Thomas J. Riley, the rector of St. John's Seminary in Brighton, that Geoghan "has a very pronounced immaturity."

"Scholastically, he is a problem," Murray wrote. While passing subjects, "I still have serious doubts about his ability to do satisfactory work in future studies," he said.

A year later, Geoghan, claiming illness, did not attend a mandatory summer camp for seminarians, after Keohane had written Riley that his nephew was going to miss the camp because he was in a "nervous and depressed state."

Riley wrote a tart response to Keohane. Keohane responded three days later, irate at the apparent suggestion by Riley that he was seeking special treatment for his nephew.

"I resent your implication that I sought favors or preferment for John," Keohane said. He also complained that Geoghan, after three years in the seminary, "is now sick, unhappy, and appears to be wrestling with his soul."

Geoghan left the seminary for a couple of years to attend the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester. He later reentered the seminary and was ordained in 1962.

Even as Geoghan's career neared its end, he won a sympathetic ear two years before he was defrocked in 1998.

In 1996, after years of allegations of sexual abuse and the more immediate prospect of criminal charges and civil lawsuits, Law's resolve in the Geoghan case appeared to waver, according to a memorandum prepared by the Rev. Brian M. Flatley, who was handling Geoghan's case for the archdiocese.

In an April 1996 memo, Flatley wrote that Law had been moved by Geoghan's own account of his troubles and had appeared sympathetic to Geoghan's request that he not be sent to a residential treatment center.

"In his recent conversation with Cardinal Law, Father Geoghan was aggressive and powerful in presenting his case," Flatley wrote. "Until I came into the conversation at the Cardinal's invitation, I sensed that Father Geoghan had made him feel uneasy."

Flatley, in a harsh evaluation that stood in contrast to earlier, more sympathetic assessments, also wrote that he believed that Geoghan "was not totally honest" with his doctors and said he could not be convinced Geoghan was "not lying again" in denying allegations that he had molested four Waltham boys.

"I see no signs that Father Geoghan has taken the steps that addicted people seem to feel are essential to recovery," Flatley wrote. "He has not joined a group, he does not attend twelve-step meetings, he has not been receiving ongoing counseling."

Two months later, in June 1996, Flatley wrote a memo to Law urging that he deal with Geoghan in a decisive manner. "I believe that Father Geoghan has deceived Doctor Messner," Flatley wrote, referring to Edward Messner, a Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatrist.

"Father Geoghan is clever," Flatley added. "He withheld information from each assessing group, only to admit a little bit more to the next tester. He is a real danger. I think he needs to be in residential care."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.