()

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

July 24, 2025

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

The new case in Atlacomulco, Mexico uncovers hurdles victims face. Instead of helping victims, State and Church protect predators.

Catholic Church’s and authority’s secrecy in Mexico hampers justice in diocese founded by Marcial Maciel’s cousin.

The latest arrest of a Catholic priest in Atlacomulco, Mexico, underscores the persistent opacity facing sexual abuse probes.

Late on Monday, Mexico City got news of yet another potential case of a Catholic priest accused of abusing underaged males under his care back in 2023.

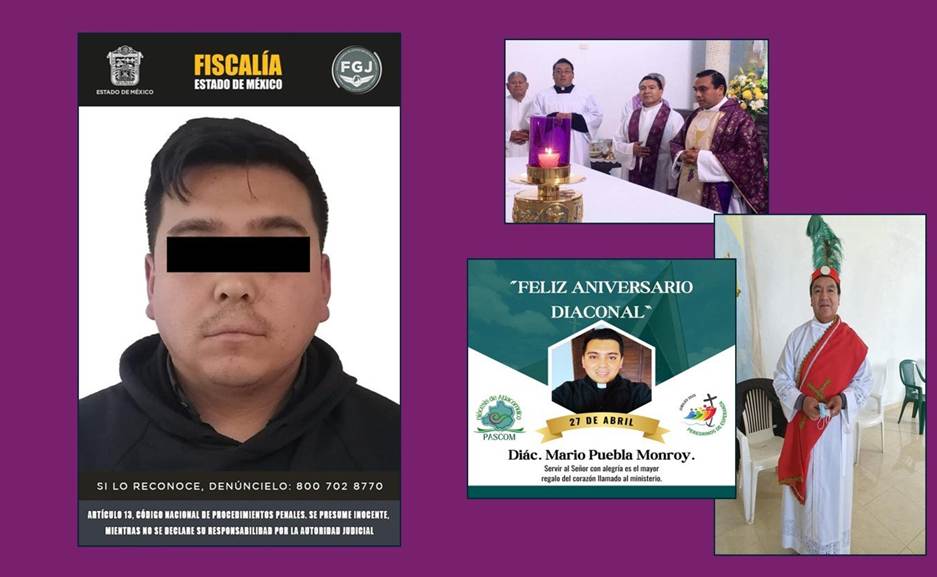

The official information is not clear as to his status as priest, as the State Attorney’s office only identifies him by his given name as Mario, and there is no actual reference there to him being a priest in the diocese of Atlacomulco, little over 50 miles or 80 kilometers Northwest of Mexico City.

Identifying Mario as a priest has been a task developed by different local media. Spanish-language TV networks like Milenio and TV Azteca, along with news websites such as Aristegui Noticias and Infobae.

Atlacomulco is relevant because it is one of the silent epicenters of the clergy sexual abuse crisis in Mexico. From that diocese, back in 2023, Los Angeles Press published a story available only in Spanish, linked after this paragraph, about Joana, now an adult, who was attacked by a group of priests then associated with the diocese’s seminary.

[México violento: Joana, víctima de abuso, exige justicia a las autoridades mexiquenses]

Joana’s case, as many others in Mexico, has made no progress over the last years, despite the fact she and her lawyers were able to prove the abuse happened during a trial in a lower court. When the priests named as guilty appealed, a superior court in the State of Mexico ruled in their favor, and now the case waits for a ruling to an appeal brought by Joana and her lawyers.

The diocese remains largely non-operational, held in a type of limbo as a vacant see by Rome. This state began when Pope Francis accepted Juan Odilón Martínez García’s resignation, which occurred less than two months after he submitted his letter to Rome. Crucially, over two months into his pontificate, Pope Leo XIV has yet to make an appointment for Atlacomulco.

Even if it is not unknown for dioceses to remain vacant, it is often when cases of clergy sexual abuse occur, as it was with the Mexican archdiocese of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, a main character in the series Los Angeles Press published about the abuse of a Mexican nun.

[English Edition: A Mexican nun‘s plea to end clergy sexual abuse in her Church]

The first installment of that series appears before this paragraph, and the whole series with some additional material is included in the bilingual English and Spanish book Breaking the silence, linked after this paragraph.

[English Edition: ‘Breaking the silence‘, a book about sexual abuse in the Church]

The fact that Atlacomulco has been vacant for over a year is particularly relevant because the so-called apostolic administrator, bishop Juan Pedro Juárez Meléndez, does not belong to any of the dioceses near the vacant see. He is the bishop of Tula Hidalgo, a city 40 miles or 65 kilometers Northeast of Atlacomulco.

As with many things in the Mexican Catholic Church, an institution known for its secretive practices, it is unclear if Juárez Meléndez is carrying something similar to a “visitation”, delivering a report to Rome on what has happened in Atlacomulco for many years, or if he is only keeping up with appearances, while waiting for Rome to appoint a new bishop.

Legacy of clans

Atlacomulco is a key diocese to understand clergy sexual abuse in Mexico as its first bishop, back in 1984, was Ricardo Guízar Díaz. He was a cousin of Marcial Maciel and, as Maciel, a member of a powerful clan in the Mexican Catholic Church, he had at least five bishops who were his uncles, on top of many other clerics in key positions, as Maciel himself.

For Guízar Díaz served as a steppingstone in a stellar ecclesiastical career as, after 12 years in Atlacomulco, John Paul II appointed him as archbishop of Tlalnepantla in 1996. In that diocese, Guízar Díaz supported Maciel’s Legion of Christ.

[PHOTO: A pictorial from the diocese of Atlacomulco with the pictures of three of their bishops. To the far left, Ricardo Guízar, Marcial Maciel’s cousin. In the middle, Constancio Miranda, now emeritus archbishop of Chihuahua, and the now emeritus bishop of Atlacomulco, Juan Odilón Martínez García. From the diocese’s social media.]

Atlacomulco becoming a diocese in the 1980s also was an olive branch of sorts to the powerful political clans identified with that rather small city in rural State of Mexico, the cradle of at least three political dynasties in that state, and with one of its members, Enrique Peña Nieto, becoming President of Mexico in 2012.

[IMAGE: The diocese of Atlacomulco, in Central Mexico.]

With the urbanization of Mexico City’s western confines, encompassing Santa Fe and the neighboring municipality of Huixquilucan, the order had been building in the Tlalnepantla archdiocese’s territory, the main campus of their flagship Mexican college, the Universidad Anáhuac.

Recently, Los Angeles Press reported on new cases of clergy sexual abuse from a key figure of the Legion of Christ, a member of Marcial Maciel’s inner circle, as the story linked after tells.

[English Edition: New cases of abuse at the Legion of Christ: Zero-tolerance is a slogan]

And if Guízar Díaz was not enough, there is in the history of Atlacomulco the case of now emeritus archbishop of Chihuahua Constancio Miranda Wechmann who has a record of his own of covering up predator clergy in that city in Northern Mexico, while eroding the Catholic Church’s reputation in Chihuahua for promoting Human Rights. He was bishop of Atlacomulco from 1998 through 2009.

It is almost impossible to know who the actual cleric is arrested Monday afternoon in Atlacomulco, as the diocese lacks a functional website. Whoever visits their URL https://www.diocesisdeatlacomulco.org/ would be led to believe Pope Francis is still the reigning Pope, as there is no notice of either his death or Pope Leo XIV’s election in the May conclave.

Even if the Facebook profile managed by the diocese has been updated, to reflect such a momentous change in the Catholic Church, it is almost impossible to find actual information about the arrest of the individual identified by several Mexican news outlets as a priest by the name of Mario.

The only way to try to figure out who could be this Mario arrested for the abuse of at least three minors in the diocese of Atlacomulco, requires going over the PDF listings of all the religious ministers registered before the federal authority.

The more than 2, 700 pages of that registry are available here as a Spanish-language PDF. There one needs to look for the priests named Mario.

When doing that, one will find four records: Mario González Martínez and Mario Guadalupe González Martínez, who are the same person, besides Mario Puebla Monroy and Mario Valencia Plata, so there are only three actual priests bearing that given name.

[PHOTO: Mario Guadalupe González Martínez, priest in Atlacomulco, State of Mexico.]

Some of the pictures used by the diocese in their Facebook postings appear before and after this paragraph.

With those three names, one must go over the “Happy Birthday” or “Happy Ordination Anniversary” messages that the community managers of the diocese’s Facebook profile have been publishing over the years and try to match those names and the pictures published by the diocese, with the sole, censored picture published by the State Attorney’s Office of the State of Mexico on its Twitter profile.

[PHOTO: Highlighted, Mario Valencia Plata, priest in the diocese of Atlacomulco, State of Mexico.]

As it should be clear, this is a system where the Church in Atlacomulco does as much as it can to never actually inform who are the priests in charge of any given parish or apostolate and the State Attorney’s Office does also its best to protect not the victims of sexual abuse but the potential predators, by limiting the access to the full name of the suspect and by censoring the picture, as the image after this paragraph proves.

Oddly enough, that page calls the public to identify a potential sexual predator, one accused so far of attacking at least three minors, by concealing as much as possible a key defining feature such as the eyes.

[PHOTO: Mario Puebla Monroy, then a deacon at the diocese of Atlacomulco, State of Mexico.]

So, it is up to the victims and the public, for whoever has the four or five hours required to go over endless postings about Masses, pilgrimages, and other public functions, to try to figure out who is in charge.

The closest parish to the site where the arrest happened, that of Saint John the Evangelist Jiquipilco has no webpage, only a Facebook profile page with as little information as possible about who are the priests in charge there.

[PHOTO: Mario, identified as such by the authorities of the State of Mexico, who call potential victims or witness to come forward, if they are able to identify him, despite the black bar over his eyes.]

It should not be difficult to figure out by now how the model is designed to make the identification of potential predators as difficult as possible.

An update of sorts

Going back to Joana’s case, which was the subject of yet another piece only in Spanish, available here, and a key element in the story in English available after this paragraph that goes over different examples of the kind of challenges victims of sexual abuse face in Mexico, Argentina, the United States, and other countries, it is possible to report that there is nothing to report.

[English Edition: From Washington to Mexico: War on the victims of sexual abuse]

That is the silent reality that victims of sexual abuse, clergy or otherwise, confront not only in Mexico or Latin America and in any country where the systems of justice lack the tools to address their needs.

This is more relevant now, as there is a clear shift in public opinion marked by the emergence of populist leaders willing to “punish” innocent workers, struggling to make a living such as Kilmar Ábrego in the United States.

This is harder to understand when they do so while dispensing pardons and impunity on groups and/or individual with a known record of abuse, in exchange for their support, as the evolution of the Epstein files seem to prove.