VATICAN CITY (VATICAN CITY)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

July 7, 2025

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

While Benedict XVI might have been “God’s rottweiler” when dealing with dissenters, he was not when dealing with predators.

On Saturday, Leo XIV appointed French archbishop Verny as new president of Tutela Minorum. Will his appointment help to overcome failures in how Benedict XVI and Francis addressed the crisis?

At the end of his 2018 trip to South America, Pope Francis credited Benedict XVI with the development of “zero-tolerance” to address the clergy sexual abuse crisis. He said, while flying from Lima to Rome:

“You know that Pope Benedict began with zero tolerance, I continued with zero tolerance, and, after almost five years as Pope, I have not signed a request for pardon.”

This claim, however, proves fragile, as two recent cases from Argentina showcase. Both parallel Chilean former Jesuit Felipe Berríos’s case, where the “solution” also involved the “extinction” of the case due to the statute of limitations.

One scandal, already decades old, involves Argentina’s social justice champion, Cardinal Estanislao Karlic. He was Justo José Ilarraz’s mentor, who was a professor at the seminary when Karlic led the Archdiocese of Paraná.

The Superior Tribunal of the Entre Ríos province found Ilarraz guilty of abusing at least seven seminarians under his charge back in the 1980s. On July 1, the Argentine Supreme Court revoked the ruling and, ultimately, set Ilarraz free for the rest of his life. The ruling is available as a PDF file here in Spanish.

The other, less known but similar, case occurred three days later when a local judge in Buenos Aires province followed the Supreme Court’s ruling, also “extinguishing” accusations of sexual abuse against Raúl Anatol Sidders.

The news from Argentina clouded the information on Saturday July 5 about Pope Leo XIV’s decision to appoint French archbishop Thibault Verny as new president of Tutela Minorum, the commission charged with preventing sexual abuse in the Catholic Church at a global scale.

After the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, the only other conference willing to seriously tackle the clergy sexual abuse crisis is the French one. One cannot dismiss how they commissioned the Sauvé Report, the most comprehensive report of its type to date. Next week this series will go over Thibault’s appointment and its potential effects.

Going back to Benedict XVI, even if one was willing to believe Pope Francis’s claim about not issuing pardons, the fact is that there are ways for predators to avoid jail or any consequence for their abuse, as the Berríos, Ilarraz, and Sidders cases prove.

During his 2018 trip to South America, Francis credited Cardinal Seán O’Malley for his own renewed understanding of the matter, but the fact remains. The Church at large finds it hard to assimilate much less to espouse the defense of the victims who, in Ilarraz’s case (all male minors) and Sidders’s case (at least one female minor), were active in their local Catholic communities and schools. All these cases happened during John Paul II’s papacy, and Joseph Ratzinger’s tenure as head of the then Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, by the end of the 20th century.

Argentine gap

There is a gap more evident now, after the Argentine rulings, between Francis’s praise for O’Malley’s intervention, and his Church’s institutional behavior, as his words on the flight back to Rome were stressing the idea of a conversion of sorts, that is not actually happening:

I have seen Cardinal O’Malley’s statement. He also said that the Pope has always defended [the victims], the Pope has zero tolerance.

What O’Malley said can be summarized in one of the paragraphs of that statement:

- Accompanying the Holy Father at numerous meetings with survivors I have witnessed his pain of knowing the depth and breadth of the wounds inflicted on those who were abused and that the process of recovery can take a lifetime. The Pope’s statements that there is no place in the life of the Church for those who would abuse children and that we must adhere to zero tolerance for these crimes are genuine and they are his commitment.

Neither Francis nor one of his closest advisers were talking about “approach,” “framework,” “policy,” or any other specific term to set the scope of their statements about “zero tolerance.”

It is not surprising how the media dealt with the situation: the Catholic Church, an entity fond of its discipline and uniformity, instead showed the depth of its internal differences.

While civil media interpreted O’Malley’s message to the Pope as either “chastising” as the Boston Herald said, or as “rebuking” in the words of German broadcaster Deutsche Welle, Vatican News framed the same intervention as a “reaffirmation” of Francis’s commitment towards survivors of clergy sexual abuse.

From the jungle to the city

This vagueness merits closer examination given the continuous emergence of new cases. And it is not only in Coari, a mostly rural diocese, lost in the middle of the Amazon forest, as the story of the Brazilian Paulo Araújo linked above proves. It happens in dioceses or orders such as the Legion of Christ in very urban, affluent Northern Madrid, as the story linked below tells.

The Legion, as other entities following U.S. consultancy firm Praesidium’s processes, adhere to zero-tolerance approaches and follow accreditation procedures that, at least in theory, should offer some warranty against abuse.

How could it be that clergy sexual abuse and scandals associated with it keep happening despite all these efforts and references to zero-tolerance?

To trace when the Catholic Church started talking about zero-tolerance, there are various possible dates: almost 20 years if crediting Benedict with the inception of this loose “zero-tolerance” idea, highlighted by his “punishment” of Marcial Maciel. Twelve years if one attributes “zero-tolerance” to Pope Francis’s decision to create Tutela Minorum. Or even seven years from that fateful in-flight press conference, from Lima to Rome, as the moment where a Pontiff used the term.

Francis elevated his predecessor’s contribution beyond what any policy assessment could. He avoided criticizing him; he also accepted his role as the first elected Pope to cohabit with an emeritus. Despite far-right narratives portraying the Argentine Pontiff as disloyal or heretical, he tried to cement John Paul II’s and Benedict XVI’s legacies beyond the sexual abuse crisis.

That is the only reason to explain how Francis risked the irate response from liberal Catholic flummoxed by his 2014 canonization of John Paul II. That was a hard-to-swallow pill for those paying attention to Karol Wojtyla’s role supporting Marcial Maciel or Theodore McCarrick.

John Paul II was also willing to protect cover-up artists like Cardinal Bernard Law, while letting Angelo Sodano, his Secretary of State, do as he pleased. Among Sodano’s many “merits” were his staunch support for notorious predators such as McCarrick from the U.S., Maciel from Mexico, Carlos Miguel Buela from Argentina, and Chilean Fernando Karadima.

And Benedict XVI’s contribution was a mixed bag of statements, the retelling of the fable of the abominable lone predator and, above all, a weak implementation even of his own ideas as to how to address the crisis.

Papal agenda

Francis had an agenda for change. He actually created Tutela Minorum in 2014, an entity detached from the Roman Curia, headed by Cardinal O’Malley, the “fireman-in-chief” of Boston, an archdiocese riddled with one of the worst cases of clergy sexual abuse. Tutela was originally the byproduct of a 2013 suggestion from the Council of Cardinals, a then new entity set up immediately after Francis’s election.

However, Francis also focused on issues closer to his initial interests. The former archbishop of Buenos Aires focused on deepening the link between theology and ecology, as his May 2015 encyclical Laudato Sì and subsequent statements on the issue prove.

Another was his interest in reforming marriage annulments, leading to a major Church law reform that same year.

Despite Francis’s interest to deal with other issues, the scandals, old and new, and the ability of survivors in the English- and German-speaking worlds to keep pressing for actual consequences, as far as Church law was concerned, forced Francis to reassess his priorities.

Besides the then ongoing cases in the U.S., it was notable the wealth of data coming from the hearings at the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

Set up one month before Francis’s election, the Australian entity offered a coherent assessment of the scale and scope of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, and in other settings, religious or secular, in that country.

Even if the Commission’s final report appeared in December 2017, the Australian government’s commitment to maintaining its archive of hearings and case reports keeps benefiting the whole world. The Commission’s findings facilitated a better understanding of abuse and pressured the Catholic and other churches there to prioritize the issue.

Also, the similarities of Australian cases to those in the United States, Canada, Mexico, or Chile underscored the systemic nature of the crisis. They proved, above all, that the crisis is not about isolated incidents. The linked piece further illustrates this scale with seven stories, one from Australia.

Seven stories of clergy sexual abuse

Sadly, not all efforts were as successful as the Royal Commission. Almost at the same time Australia was launching its commission, in Germany, on January 9, 2013, media reported the abrupt ending of what, otherwise, would have been a major report on abuse in Ratzinger’s country of origin, as the BBC reports here.

Despite the failure to bring that report to fruition, the German survivors have been able to keep pressing for changes, and they have had a measure of success in some areas. So much, that fragments of that failed report have been known since 2018.

Chilean odyssey

Francis was far from rushing into changing the ways his Church deals with abuse. When taking Juan de la Cruz Barros Madrid from the Chilean Military diocese to Osorno, he was indirectly supporting John Paul II’s appointment of Barros as auxiliary bishop of Santiago, the capital of Chile, back in 1995.

From there, the Polish Pope sent Barros to Iquique in 2000. His stint there was brief, as he got a promotion as head of the Military Diocese, a then-prestigious position in Chile.

He remained there for eleven years, until Francis decided to move him to Osorno. Although not elevated to archbishop, going to Osorno, a diocese, 500 miles or 800 kilometers, South of Santiago, allowed Barros to advance his career.

Francis made this move in 2015 when abundant accusations already existed against Barros’s mentor, Fernando Karadima, along with rumors about Barros’s own role as first accomplice and then protector of Karadima’s wrongdoing.

Back then, Rome had already “punished” Karadima even if his superiors at the archdiocese of Santiago were unwilling to at least enforce that “penalty,” as the previous installment of this series explained.

Karadima’s case disproves any meaningful enforcement of something close to a zero-tolerance approach, much less a clearly stated, enacted, and enforceable policy, as Francis tried to portray his predecessor’s contribution on the issue during the flight back to Rome.

Benedict XVI seemed to be happy with the lone predator narrative put forward originally by Charles Scicluna, the Maltese archbishop and official at the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, who was in charge of the original probe on Marcial Maciel. It is possible to say so, as there is no actual record of any attempt at setting clear consequences for failure to comply with his own reforms.

The lone predator and the “blind” overseer

It was then, with Maciel, that Scicluna wrote his own Gothic novella: Maciel as the abominable lone predator, able to abuse scores of victims, without the ever-vigilant Catholic hierarchy figuring out what was happening. Just as a side note, the roots of “bishop” in Greek come from episkopos: overseer.

Scicluna would go for the sequel in his first stint probing Karadima, almost plagiarizing his own ‘explanation’ of Maciel’s superhuman ability to fool dozens of Catholic “overseers.” A character able to challenge Dracula or a Leprechaun due to his ability to disappear in plain sight.

Neither Benedict XVI nor any of the key players in his curia saw a need to go beyond that fable. No one was willing to acknowledge that behind characters like Maciel or Karadima, at least in the Scicluna’s first probe, there was a wide network of overseers willing to see elsewhere.

And it was not only the Maltese archbishop. Back in April 2010, at a time when the Chilean Conference of Bishops usually has a meeting, Benedict XVI’s Secretary of State, and a former secretary of Ratzinger himself (1995-2002) at the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, Tarsicio Bertone, went to Santiago.

Officially he was attending the celebrations of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. But, while there, he conveyed in a press conference the usual chain of homophobic innuendos about the “actual” root-causes of the clergy sexual abuse crisis there and elsewhere.

UPI reported then a summary of Bertone’s remarks. The Cardinal’s implicit attack on gay persons prompted condemnation from the French government, as this story in Spanish from Chilean medium Biobiochile reports.

Francis’s deference towards his predecessor during his Damascus moment was an attempt to build a battleship out of cardboard. A nice gesture, one that the Catholic far-right has never been willing to acknowledge, as they would rather stick to the self-serving narrative of “God’s rottweiler”.

Later that year, in May, Francis called all the Chilean bishops to Rome and asked their resignation. In doing so, he was showcasing the kind of systemic issues happening there and in many other countries. Otherwise, why would all be asked to do so? It was a tangible proof of the limits of John Paul II’s and Benedict XVI’s management of a systemic crisis.

At least as many systemic issues as those allowing for the emergence of noted predators like Maciel in Mexico or Buela in Argentina (one of Theodore McCarrick’s partners in crime), as the story linked after this paragraph shows.

It was only mass mobilization, the vigorous rejection of Barros by the people in Osorno and other cities in Chile, coupled with the empty streets and venues during Francis’s pilgrimage to Chile, topped with Francis’s impromptu interview on Argentine TV that made Barros’s position as bishop untenable. The combination of these and other factors forced change in Vatican’s discourse about the clergy sexual abuse crisis in Chile and elsewhere.

Limbo

Francis accepted Barros’s resignation, and he remains in some sort of limbo as of today. As far as is known, neither Francis nor the Doctrine of the Faith issued an actual sanction on him. In 2018, he became emeritus at 61, a “mini-defrocking” of sorts, with little or no evidence of an actual punishment, a measure rather short of elevating the rhetoric about zero-tolerance to the status of a policy.

As in many other cases, his resignation remains part of the rather toxic guessing game the Catholic Church imposes on its faithful every time a bishop resigns his position before reaching 75.

Moreover, as luminous as Francis’s Damascus moment was, before that experience, he dug his heels in defense of Barros, and more significantly of a model of how to address clergy sexual abuse.

Bergoglio changed gears, discourse, and attitude towards the crisis. To find a case of a Pope retracting a bishop’s nomination out of popular pressure, as he did with Barros, one would have to dig into the history of Medieval Christendom.

And the same is true about Francis’s decision to publicly admit, during a press conference, that he was wrong. One only has to remember how manicured Benedict XVI’s press conferences were, with Jesuit Federico Lombardi, his spokesman, carefully picking up written questions he would read to his boss.

Despite Francis’s display of charm and communication abilities, a gap remains between the very ambitious implicit goals of Catholic Church leaders when they talk about zero-tolerance and the harsh realities survivors experience.

Tutela remains a felicitous idea but, so far, an idea, a promise, and nothing else, as there was no actual compliance with Pope Francis’s original request to set up at least one commission to prevent clergy sexual abuse in each diocese. Some countries went for national solutions, to save resources, but in countries such as Mexico, less than half the dioceses in the country complied.

[Less than half the Mexican Catholic dioceses prevent sexual abuse]

Despite that fact, as detailed in the story linked above, when the Mexican bishops delivered their report to Tutela back in 2024 they claimed full compliance (see the story linked after).

There, it is possible to see how, beyond the fact that fewer than half the dioceses actually published proof of compliance on the Mexican Conference of Bishops website, there is a wide array of setups.

[English Edition

[The Catholic Church’s report on clergy sexual abuse]

One diocese stands out: Saltillo, capital of the state of Coahuila, where the bishop is willing to make himself accountable to the civil authority, since one member of the diocesan commission is a representative of the State Attorney’s office. Others simply stack the commission with priests from the same diocese, as in the case of the Port of Veracruz.

In that respect, it is unclear what prompted Cardinal O’Malley’s decision to meet with Francis in Peru and make him aware of how dangerous it was to revert to the old strategy of asking for evidence of Barros’s role in Karadima’s abuses. But it would be necessary for each bishop in Latin America to see himself in Pope Francis accepting his mistake and acknowledging the need to change.

Dueling clerics

To understand what happens in Mexico, Argentina or Chile and in Tutela’s evolution, it would be necessary to dive into the corporate culture of Catholic entities.

Since that is impossible here, suffice it to say, regarding Tutela, that Marie Collins, an Irish survivor of sexual abuse and one of its original members, resigned in 2017. She did so while lamenting the Curia’s unwillingness to acknowledge the entity’s needs and to facilitate its operation and goals.

Ms. Collins remained a critic of Pope Francis’s take on the Commission even after the 2019-22 reforms. While Francis, O’Malley, and the Vatican curia saw fit to integrate Tutela within the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, survivors such as Collins regretted it.

Her perception was that, in doing so, Tutela lost its original identity as an ad hoc entity reporting to none other than the Pope himself. Tutela has a certain degree of autonomy as it has now its own offices, officials, statutes, and some money to work with. However, that was possible only in the midst of a financial scandal that found its scapegoat in then secretary of the commission, Oblate priest Andrew Small.

Small addressed the pressing need to deal with basic financial needs that the Vatican’s bureaucracy was either unable or unwilling to solve. Small saw fit to appropriate funds from charitable works developed by the Church at large, bringing him and another former member of the commission, Jesuit Hans Zollner, into a media OK Corral shootout.

There were leaks of bits and pieces of information to both civil and Catholic media in the English-speaking world, but with no actual transparency. What was clear, however, is how easy it was for Catholic officials to use survivors of clergy sexual abuse as pawns of their intrachurch conflicts.

Francis was able to finance Tutela’s work, but the situation reveals there was no support for the Argentine pontiff’s goals for the Commission. This was despite his decision to strengthen its powers and to request the conferences of Catholic bishops to set up similar commissions for every diocese. A list of current and former members of the Comission is available here.

The response to Francis’s requests is the very epitome of how far the Catholic Church is from adopting a zero-tolerance policy, and how it remains a slogan.

The pattern of loose compliance is not exclusive to Mexico, the world’s third most populous Catholic country. A similar pattern emerges across Latin America, as the story linked below further explains.

[English Edition

Commissions to prevent clergy sexual abuse in Latin America, a report]

Even if Francis’s Damascus moment is relevant because he was willing to accept his own mistake, an oddity in an institution whose leader claims to be infallible, it is hard to assume that his plea to zero-tolerance is more than a fashion of sorts.

It is a useful rhetorical device used when bishops try to find a way out of the minefield that is their interactions with the media, but also a somewhat remote expression of interest in achieving a far-removed goal at an unknown date.

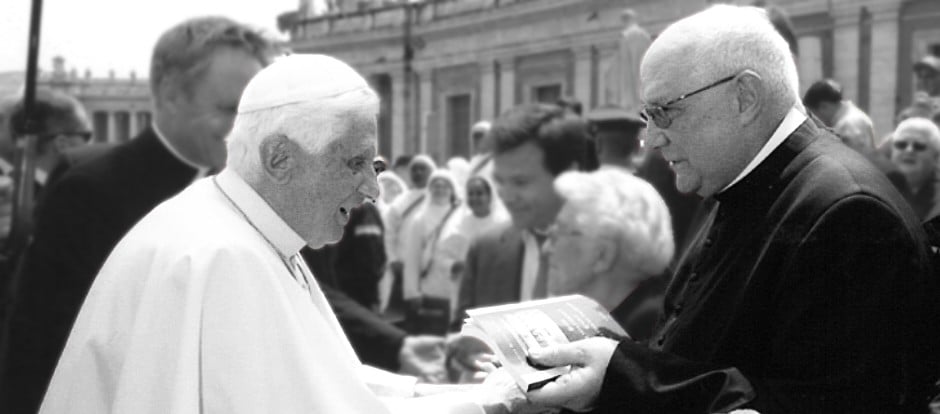

God’s rottweiler

Is there evidence to support Francis’s claim about Ratzinger being the forerunner of zero-tolerance in the Catholic Church?

Prior to his Pontificate, as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Prefect of the Doctrine of the Faith, and as such responsible for handling abuse cases, he earned praise from conservative Catholic pundits such as George Weigel.

Already in 2005, Weigel, John Paul II’s biographer, was comparing the German Cardinal with a rather fierce and uncompromising breed of dogs in Newsweek. Other outlets followed Weigel’s praise of the Bavarian pontiff, as this BBC story proves.

The monicker came to be a badge of sorts during his 24-year stint at the Doctrine of the Faith. There, he issued a letter under the title De delictis gravioribus, meaning The worst crimes. The document is available here.

The actual reform, however, came with John Paul II’s decree called in Church parlance a Motu Proprio, its Latin title, Sacramentorum Sanctitatis Tutela, akin to “The protection of the holiness of the sacraments.” Wojtyla issued this document, a few days before, on April 30, 2001.

Nine years later, already as Pope Benedict XVI, Ratzinger issued a letter to the Church in Ireland dealing explicitly with abuse; and a few days after, a document with a similar Latin-language title to his letter as prefect of the then Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Normae de gravioribus delictae, meaning Rules or norms dealing with the worst crimes.

Between those dates, Benedict XVI issued a document he had been preparing for John Paul II’s signature. The document’s main purpose was to set a framework for the criteria dealing with seminary formation in the Catholic world. It is not a document explicitly addressing the clergy sexual abuse crisis, but it is reflective of the then-existing consensus in the Roman Curia about how to deal with the issue.

Scapegoats

The underlying assumption of the 2005 document, available here, is that clerics ‘affected’ by same-sex attraction are to blame.

The proposed remedy is simplistic: remove gay candidates to the priesthood. The weakness of this remedy is clear when one considers that bishops circumvented the regulation, as they found it impractical to reject candidates to priesthood or religious life, for their sexual orientation. Even if informally, they acknowledged that it oversimplified and used same-sex attraction as a scapegoat.

Even here the lack of teeth in Catholic policies is evident. Why, if it was actually so relevant, Benedict XVI was unwilling to attach specific punishments for non-compliance?

More relevant is the fact that the Catholic Church is coming to acknowledge, at least in Italy, 20 years after, that Benedict XVI’s reform of seminaries was actually unenforceable. By the end of 2024, the Italian Conference of Bishops issued what is now an experimental move away from that other aspect of Benedict XVI’s legacy when dealing with the clergy sexual abuse crisis. Early this year, Los Ángeles Press went over the Italian reform, as the story linked below shows.

[English Edition

[New interpretation of old rules at Italian seminaries]

A few days before the 2010’s amendments, Benedict XVI issued a Letter to the Catholics of Ireland, acknowledging his “shame and remorse.”

Although there is no explicit use of zero-tolerance, he used the notion of accountability in one paragraph, while also talking about the need for proper application of canon law, and cooperation with civil authorities.

True reach

The most favorable interpretation of Benedict XVI’s pontificate puts the 2001 letter (as Cardinal), his 2010 decree and letter to the Irish faithful, and his disposition to meet with survivors of abuse in countries such as the United States and Australia (2008), the United Kingdom and Malta (2010), and his native Germany (2011) as proof that he was willing to acknowledge the issue.

However, during his 2012 trip to Mexico, there was no meeting with survivors, public or private. Indeed, Benedict held no survivor meetings during his numerous other international trips, including to Spain, Brazil, and Portugal, to name a few.

Overall, Ratzinger (2001) and Benedict XVI (2010) aimed to centralize abuse cases under the control of the Congregation, now Dicastery, for the Doctrine of the Faith. The stated aim was to develop more uniform and rigorous canonical procedures, including the possibility of automatic dismissal from the clerical state for certain grave offenses. While it is impossible to find the idiom “zero-tolerance,” it marked a shift towards a stricter, more centralized approach.

Those, as Pope Francis, willing to rescue Benedict XVI’s tenure as pontiff, see his ruling regarding Maciel as some sort of “decisive action,” advancing the notion of zero-tolerance following the USCCB’s steps. But even if someone were willing to see the 2006 slap on Maciel’s wrist as “severe sanctions,” there was no acknowledgment of abuse, only scarce details of the “penalty” surfacing after his death (2009), and there is no evidence of enforcement of said restrictions.

It fell short of acknowledging the systemic nature of the crisis and how whole dioceses and orders facilitate and tolerate abuse. With Scicluna’s and others’ help, Benedict XVI bet on the lone predator narrative when dealing with Maciel and Karadima, as that narrative helps to absolve clerics involved, even if passively, in those predators’ abuses.

[English Edition

[Hero, priest, and sexual predator: the story of Abbé Pierre]

This narrative was useful because many predators play some role as a philanthropist or used similar functions that gave them some measure of power. From Maciel in Mexico to Julio César Grassi in Argentina all the way to Abbé Pierre in France, they all used philanthropy and charity as a means for harming minors or adults, males and females alike.

Conflict of interest and accountability

Clergy abuse would not happen without tolerance of conflicts of interest and lack of accountability. Until recently, dioceses and orders were unwilling to acknowledge the risks inherent in conflicts of interest. Dioceses and orders accepted the risk of having clergy from the same diocese or order investigating their own.

Some U.S. dioceses, affected by this kind of experience, as Saint Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, have come to the realization that risk persisted until recently. A policy assessment commissioned by them underscores this, urging them to acknowledge the issue when enforcing policy.

Saint Paul and Minneapolis, an epicenter of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, is relevant as, back in 2015, Rome actively forced out of office two bishops working there, archbishop John Clayton Nienstedt and his auxiliary Lee Anthony Piché.

Even worse, Benedict XVI, God’s rottweiler, if one believes the far-right’s praise, appointed Nienstedt there as coadjutor in 2007. Rome accepted his predecessor’s resignation, that of the now deceased archbishop Harry Joseph Flynn the very day he turned 75.

Flynn’s case would merit a book on its own, as it was an open secret that mishandling of abuse clouded his tenure, despite his support for Wilton Gregory’s development of the Dallas Charter and his own fame as a bishop known for specializing in this issue.

Back in 2003, The New York Times called Flynn a “healer,” as to acknowledge his expertise on dealing with abuse from his days in Lafayette, Louisiana (1986-94), the state where the clergy sexual abuse crisis first exploded.

Good intentions

Flynn’s first appointment as bishop turned him into an expert of sorts in rescuing dioceses from the depths of chaos. In the end, his reputation as healer backfired, as this other piece from Minnesota Public Radio from 2014 tells.

Tracing back through the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, the task of Flynn, Nienstedt, and Piché was to deal with clergy sexual abuse in the Twin Cities. Despite the expectations of their appointments all three failed.

Nienstedt was a darling of the U.S. Catholic far-right even after his inglorious exit in 2015, as evidenced by how the Napa Institute took Nienstedt on as a chaplain of sorts, a position he had to leave by 2018.

As well-intentioned as the Dallas Charter was, it lacked the teeth to force bishops to follow procedure. That is why it is hard to accept the idea that one could find in the Dallas Charter (2002) or in Benedict XVI’s management of the crisis something other than the will to acknowledge that something awful had been happening.

As with Flynn’s “healer,” Ratzinger’s title as “God’s rottweiler” or as a forerunner of a new era of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, as Francis portrayed, was praise for the better angels of their nature, but also a reminder of how short they were from standing for survivors of sexual abuse.

When, in 2022, Tim Busch, the heir of the brewery’s fortune and head of the Napa Institute, issued an Op-Ed to mark the death of the emeritus pontiff using the title of God’s rottweiler, it was surely as praise. However, if one reviews his tenure at the Doctrine of the Faith and as pontiff, it is easier to find punishments against unorthodox clerics than against predators.

That was the case of French and Australian bishops Jacques Gaillot and William Martin Morris, respectively.

It was up to John Paul II to sanction Gaillot back in 1995 at the behest of Ratzinger in one of the oddest moves ever in Vatican politics. Pope Wojtyla appointed Gaillot as bishop of a so-called “historical see,” one that no longer exists in reality.

Such appointments are frequent when dealing with auxiliary bishops or papal nuncios, but not with active bishops, and certainly not for removing them from office. Gaillot became the bishop of Parthenia, while a new bishop was taking over Évreaux, France, without any formal explanation of the move.

With Morris, already as Pope, Ratzinger was straightforward. It was a punishment for Morris’s challenge to the Vatican on female ordination.

And yet, Rome’s attitude regarding the removal of bishops or superiors accused of either abuse or cover up, is a relative novelty, dating back to 2019, when Francis set new rules for those cases.

Before Francis, it was rather impossible to pursue bishops or superiors, as the cases of Maciel and Francisco José Cox Huneeus, prove.

Cox Huneeus’s case is a relatively unknown one, as John Paul II quietly removed him from office. Without informing about his serial attacks on minors, Karol Wojtyla “sentenced” him into “a life of prayer” at a Fathers of Schönstatt house in Germany. It was only after Francis’s trip to Chile, 21 years after his removal, that Rome defrocked Cox at 84. He died two years later, in 2020.

So, while Ratzinger/Benedict XVI centralized in Rome the handling of abuse cases and introduced stricter procedures, his approach relied on flawed narratives. His preferred “explanation” was the lone predator, a true Catholic fable, with Maciel and Karadima as examples. The other was the weaponizable “blame-the-gay” riff, as illustrated by his 2005 reform of seminaries or by Bertone’s 2010 trip to Chile.

Therefore, it is really hard to see him as a champion, or even a pioneer of zero-tolerance. Pope Bergoglio advanced with Vos Estis Lux Mundi, akin to You are the Light of the World, a reform that allowed dealing with abusive bishops and other top clerics but, once again, his well-intended aims lacked the necessary teeth to become a credible zero-tolerance policy or even approach.

And last week’s rulings regarding Ilarraz and Sidders in Argentina, and a couple of weeks before that in Chile with Felipe Berríos, all three related to the statute of limitations for their crimes, are a painful reminder of this reality for the survivors, their relatives, and friends.

As an Argentine survivor shared with me via WhatsApp:

I personally know the survivors of Ilarraz. I was in Paraná before the trial. I think about them, and I embrace them. Going through INJUSTICE is devastating. I lived that.