()

Chicago Sun-Times [Chicago IL]

August 1, 2025

By Robert Herguth

[See also the letter by Archbishop Filippo Iannone, O. Carm., Prefect of the Dicastery for Legislative Texts (in Italian with English translation), offering his “observations” and “negative” answer to an anonymous bishop’s question about the posting of lists of credibly accused. Iannone cites Pope Francis’ Reflection Points, no. 14.]

A Vatican opinion released shortly before Pope Francis died advises against public church listings of clergy members deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abuse — which virtually every American diocese has.

As part of their stated commitment to transparency and healing over the decades-long clergy sex abuse crisis, all six Catholic dioceses in Illinois post public listings online that name clergy members deemed to have been credibly accused of molesting children.

So do the Diocese of Gary, which covers northwest Indiana, and the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, which includes Kenosha and Walworth counties. Most of the archdioceses and dioceses in the United States have some version of public disclosure, as do many of the Catholic religious orders that often span multiple diocese boundaries.

That’s something victims, church reformers and some clergy have pushed for.

But one of the last diocesan holdouts without such a list — the Diocese of Grand Rapids, Michigan — recently signaled it has no intention of creating one. And it’s citing a little-known Vatican opinion, released by an arm of the church’s bureaucracy months before Pope Francis died, frowning on such transparency as possibly unfair to the accused.

“After being instructed by the Holy See’s Dicastery for Legislative Texts, we do not intend to publish a list,” a spokeswoman for Grand Rapids Bishop David Walkowiak recently said.

That ecclesiastical jurisdiction is among the first in the United States to point to the Vatican opinion as justification for not creating what’s essentially a sex offender registry for accused child molesters in the church.

It’s unclear how many other church organizations might follow suit into what some fear could be a retreat to the secrecy that helped define the abuse crisis.

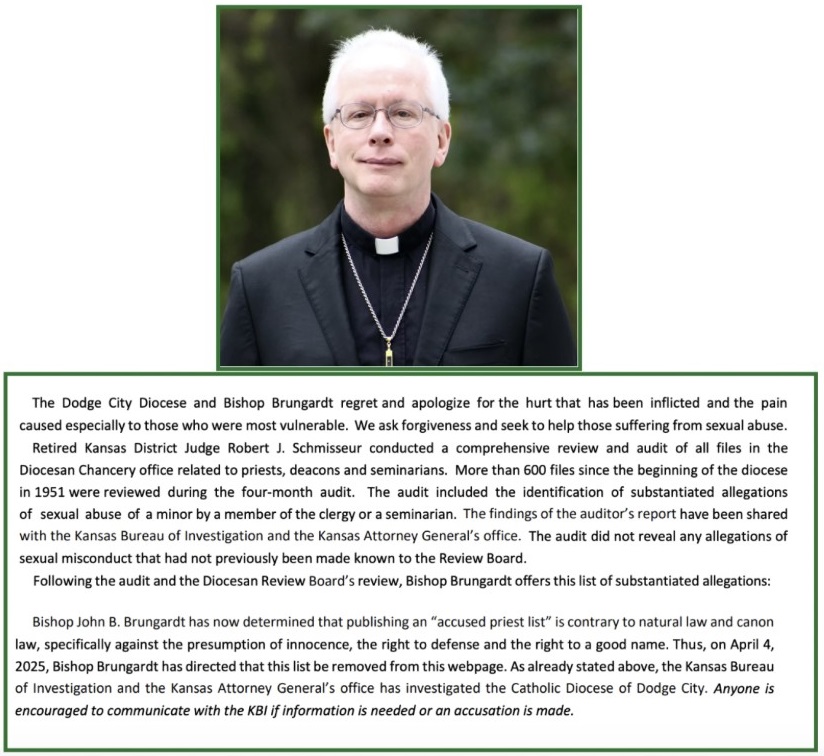

Another diocese, in Dodge City, Kansas, removed its list of 16 credibly accused priests and seminarians in April after the Vatican ruling was released. Its bishop said “an accused priest list” is “contrary to natural law and canon law, specifically against the presumption of innocence, the right to defense and the right to a good name.”

Peter Isely of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests says this marks “a significant regression” and “a tremendous step back” in church transparency that he says has benefited abuse victims and the public.

Isely says the church’s existing lists should be bolstered “with more information” rather than shrink or go away, noting that the abuse crisis isn’t over.

At some point, Pope Leo XIV, Pope Francis’ successor, could clarify the church’s stance.

His office wouldn’t comment.

The Chicago native born Robert Prevost, Pope Leo helped lead the Augustinian religious order whose province covering the Chicago area released its first public list in 2024, years after most other Catholic orders.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, composed of the church’s American leadership and led by Archbishop Timothy Broglio, won’t say whether it’s advising the church hierarchy on the issue.

The Archdiocese of Chicago, the arm of the church for Cook and Lake counties led by Cardinal Blase Cupich, didn’t respond to questions. Bishop Ron Hicks, a former Cupich aide who oversees the Diocese of Joliet, which includes DuPage, Kendall and Will counties, didn’t respond to emails seeking comment. Bishop David Malloy of the Diocese of Rockford, which includes Kane and McHenry counties, didn’t respond to calls or emails. Officials with the Diocese of Belleville and Diocese of Peoria either couldn’t be reached or had no comment.

Bishop Thomas Paprocki, a Chicago priest overseeing the Diocese of Springfield, “is aware of the document from the Dicastery for Legislative Texts,” and the diocese “is studying its implications,” his spokesman says.

Paprocki was among the bishops criticized in a 2023 report by Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul chronicling clergy sex abuse in Illinois.

Beyond excusing the secrecy and “inaction” of his predecessors, Paprocki didn’t create a public list until late 2018, after “being pushed to do so by the attorney general” as “the last diocese in Illinois to take the measure,” the report says. The Springfield list initially “was not easily accessible on the diocese’s homepage,” and Paprocki waited four years after the state agency “pointed out to diocese leaders the failings of such a hide-and-seek exercise in ‘transparency’” to fix it, the report says.

Cupich embraced broader transparency only as Raoul’s report was about to be released, initially excluding from his public list the names of credibly accused members of religious orders who’d served in the archdiocese’s territory — and clergy with credible accusations made after their deaths.

While the Vatican opinion was critical of public church lists in general, it took particular aim at the registries that posted names of priests after they had died and couldn’t defend themselves.

Church law “establishes a general principle prohibiting slander and defamation . . . declaring that ‘it is not lawful for anyone to illegitimately harm the reputation one enjoys,’” the Vatican office wrote, according to a translation from the original Italian. “This means that in some cases, harm to one’s good reputation can be legitimate, for example, to avoid any danger or threat to individuals or the community.”

But “it would not be legitimate at all when such a risk can reasonably be excluded, as in the case of deceased alleged criminals, where there can be neither a legitimate nor proportionate reason for the damage to reputation,” according to the opinion, which was requested by an unnamed church official.

The spokeswoman for the Grand Rapids diocese — once home to an Augustinian seminary Prevost attended — says her bishop didn’t make the request.

The Vatican office wrote that it “seems inadmissible to justify the publication of such information on alleged reasons of transparency or reparation (unless the subject consents, thus once again excluding deceased persons).

“The legal problem, however, is not limited to the impossibility of a deceased person defending himself against accusations, but concerns at least two universally accepted principles of law,” including “the principle of presumed innocence of everyone, until proven guilty in a court of law.

“These principles . . . cannot reasonably be overridden by a generic ‘right to information’ that makes any kind of news public, however credible, to the concrete detriment and existential damage of those who are personally involved, especially if it is inaccurate, or even unfounded or false, or completely useless, such as information concerning deceased persons.

“Furthermore, the determination of whether an accusation is ‘well-founded’ often rests on a non-canonical basis and requires a relatively low standard of proof, resulting in the publication of the name of a person who is merely accused, but not proven guilty, without the benefit of any exercise of the right to defense.”

The Vatican opinion cites Pope Francis’ critical comments about the lists, though he also emphasized the importance of transparency regarding the abuse crisis, which came into public view in the United States in the 1980s and more so after the Boston Globe’s 2002 investigation into child rape by priests and cover-ups by the church.

Reforms were put in place in the United States, including a ban on credibly accused priests ever again serving in public ministry and a pledge of transparency.

Citing the importance of that transparency, bishops in the Diocese of Tucson, including Gerald Kicanas, who is from Chicago, in 2002 created what’s believed to be the first public listing of abusive clergy. The Archdiocese of Baltimore also released a list around that time, and other church groups followed, sometimes as a condition of lawsuits or bankruptcy proceedings that followed legal claims over sex abuse.

Only when the third and current wave of the scandal broke in 2018 — in large part because of the release of a Pennsylvania grand jury report revealing hundreds of abusers — did many other dioceses and religious orders follow suit with public lists.

Pope Francis could have mandated such accounting but instead left it to individual dioceses and orders to decide whether to create lists.

As the Chicago Sun-Times has reported in a series of stories over the past several years, the result has been different levels of disclosure that have left the public without a full understanding of the scope of the scandal.

Even if additional lists aren’t posted by church authorities, the names of abusive clergy might become public in other ways. Church officials have to report abuse accusations to law enforcement. And lawsuits over abuse could result in public disclosures.

Also, groups including the nonprofit Bishop Accountability organization maintain a database of many of the accused.

That database lists 15 accused men who once served in the Grand Rapids diocese. Among them is a now-deceased Dominican priest who had served in River Forest.

“When an accusation is deemed credible, we release the priest’s name to the faithful, the parishes in which he served and the media,” the Grand Rapids diocese spokeswoman says.

But critics say there’s a difference between a formal church registry — which can readily be accessed and be added to, with names substantiated by the church — and notifications that might appear online and then disappear or not be easily found without a central online home.

Some victims say the public listings offer an acknowledgment of their suffering and amount to a victory over church secrecy of the past.

The Jesuits, a Catholic order with a large presence in the Chicago area, where it oversees Loyola University Chicago and several Catholic high schools, has a history of abuse and secrecy but released a list in 2018 that’s considered a gold standard in church disclosure.

Asked about the Vatican opinion on lists, a spokesman for the Jesuits says: “We’re aware of the opinion you mentioned. At this point, we have not considered altering our public list.”