LYNCHBURG (VA)

The Roys Report [Chicago IL]

September 23, 2025

By Julie Roys

Liberty University, a power center for evangelical Christianity and one of the country’s largest educational institutions, claims it adheres to the highest ethical standards. But while students were forced to follow the school’s honor code called “The Liberty Way,” leaders at the top flagrantly violated it, says 1996 graduate and former admissions counselor Rachel Beck.

Beck, who’s going by her maiden name, says she was sexually harassed in the late 1990s by two top administrators. They are John Borek, then-president of the prominent Christian school in Lynchburg, Virginia, and Jay Spencer, a former vice president.

But when the harassment came to light in 1998, Borek suffered no consequences, Beck says. Spencer resigned under pressure, but received a hefty severance, she claims, and was “repositioned” by Liberty founder Jerry Falwell, Sr., to an executive position at the American Association of Christian Counselors.

Eight years later, Liberty rehired Spencer, where he worked another 10 years—first as an academic dean and then as vice provost of Liberty University Online Academy. Spencer, who now goes by “Bobby,” currently works at Houston Christian University as the associate provost of online learning.

Borek, who resigned from Liberty in 2004, remains on Liberty’s trustee board.

Meanwhile, Beck says she languished for many years with far less support and financial recompense due to a cruel double-standard at Liberty and the “good ole boy network” that runs the school.

Back in 1997-1998, she was able to escape President Borek’s stalking and invitations to go hot-tubbing only when she confided in Spencer, her boss, who pledged to protect her, Beck told The Roys Report (TRR).

Instead, Spencer groomed her into a sexual relationship, she said. And though he was at least 10 years older and her superior, their relationship was labeled an “affair” when it was discovered in August 1998.

Feeling like she wore “a scarlet letter,” Beck fled Lynchburg for her hometown in Washington state, leaving most of her belongings behind. And though the late Falwell, Sr., promised to pay to ship her possessions across the county, the school reneged on that promise, she said.

Scared and distraught, the 5-foot-2-inch Beck said she dwindled to 91 pounds and had to hire a lawyer and enter mediation with Liberty to retrieve her belongings. The result was a 1999 settlement that constrained her to silence about Spencer’s and Borek’s alleged misconduct and Liberty’s cover-up.

A couple years ago, reporters who heard about Beck’s story began contacting her. Beck began reading about the lawsuits against Liberty—like the one brought by the 22 “Jane Does,” alleging that Liberty created an environment that enabled on-campus rapes.

She also read about the record $14 million fine levied against Liberty for violating the Clery Act by failing to report campus crimes. Beck was especially moved reading about two former Liberty University Title IX officials, who alleged in a lawsuit that they were fired for speaking up about systemic compliance failures at the school.

“This is where I get a little emotional,” she told TRR in a podcast interview. “People standing up for stories just like mine, and Liberty firing them over that, and realizing that it’s time. It’s got to stop.”

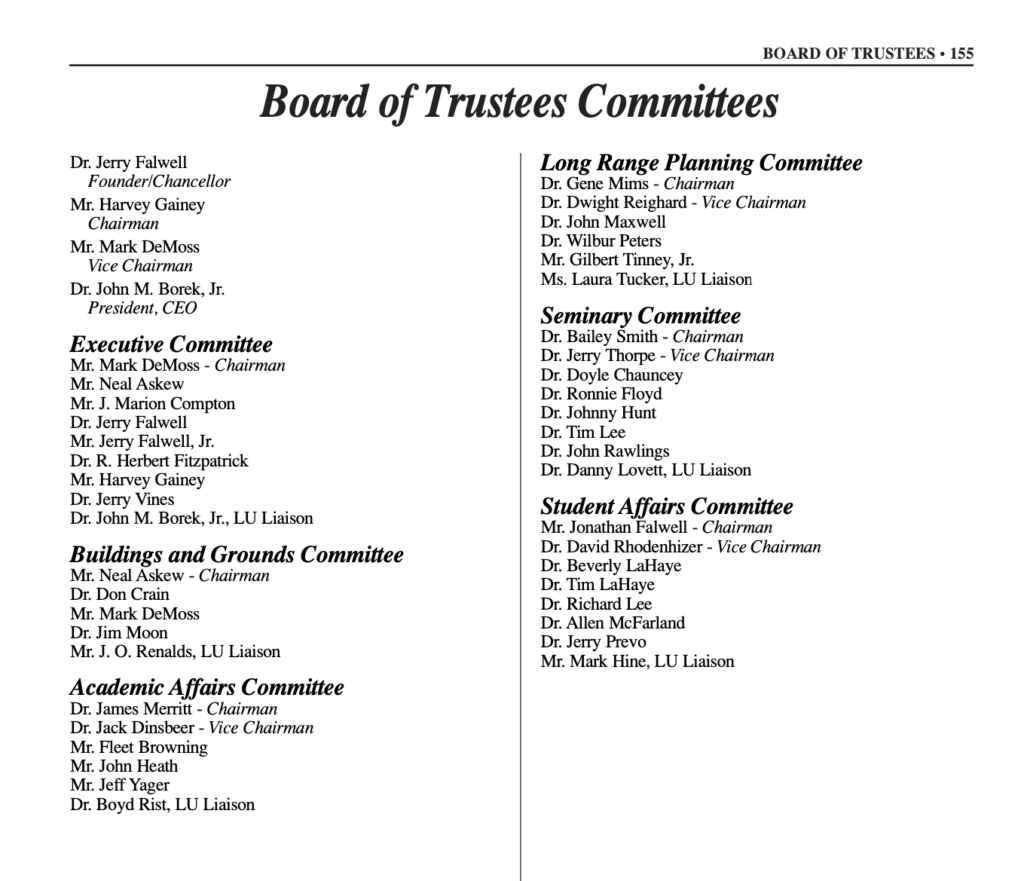

Beck noted that 16 of the 32 trustees on Liberty’s board today were also on the board 27 years ago when Liberty settled with her.

“It’s the same men that have continued the story for almost 30 years. . . . They’ve created a culture there . . . that they all cover up for each other.”

In response to TRR’s request for comment, a Liberty University spokesperson said in a statement:

. . . The allegations against Jay Spencer and John Borek were fully addressed through an investigation, mediation, and a settlement agreement that was executed more than 25 years ago. Based on Spencer’s confession, the conflicting response from Borek, as well as other information from that time, the University asked Spencer to resign and felt it appropriate for President Borek to continue in his role. Since then, Liberty has received no additional information about the incident or new allegations about those involved. More than eight years after these matters were disclosed and settled, Spencer was rehired by the University as an Academic administrator and served for a period of more than ten years before leaving for another opportunity. . . .

Spencer also replied to our request for comment, stating, “This matter was formally addressed and mediated nearly 27 years ago, and I have had no contact with Ms. (Beck) since that time. It is regrettable that she now feels compelled to revisit such a difficult chapter from our past, and I sincerely hope she is able to find the closure and peace she seeks.”

‘There was such an element of control’

In 1997, Beck, then 23, got a job as an admissions counselor at Liberty under Spencer, who was vice president of enrollment management at the time. Needing to make some extra money, she took a part-time job as an assistant in President Borek’s office.

Borek, who was hired in June 1997, may have seemed an odd hire for Liberty, since the school is distinctively evangelical, and Borek was Catholic. But in December 1996, the organization that accredited Liberty, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), placed the school on probation due to Liberty’s large debt load.

As a member of SACS’ Criteria and Reports Committee, Borek was uniquely positioned to help Liberty regain its full accreditation. In December 1997, just six months after Borek was hired, SACS restored Liberty’s full accreditation status.

Around the same time, Borek’s odd behavior was making Beck extremely uncomfortable. Borek would call her cell phone as she was driving home from work to say he was behind her, forcing her to “take different roads home, so he wouldn’t know where I lived,” she said.

Beck recalled Borek, who was married, inviting her to go “hot tubbing” at his condo 11 miles from campus in Forest, Virginia. She said she also once walked into his office and saw a female colleague sitting on his lap.

“And he proceeded to tell us how he wanted to buy us black cocktail dresses and fly with him on his Cessna to Washington, D.C. to go see the opera La Bohème,” Beck said. “And he wanted to walk with us both on each arm.”

Borek also invited Beck to see an on-campus play with him, she said. Since she felt uncomfortable going alone with Borek, Beck said she invited another woman who worked in the admissions office to join them.

TRR contacted this woman, who wished to remain anonymous, to confirm she remembered this incident. The woman did, adding that Beck communicated her discomfort with the invitation. She ended up accompanying Beck and Borek to the play.

Beck said she didn’t think of reporting the misconduct to Human Resources at the time.

“Who do you tell?” remarked Beck, who said she wasn’t “raised to push back” against any male or spiritual authority figures.

“Here, you’ve got the president of the university who’s brought in to make sure Liberty keeps its accreditation,” Beck commented. “Like, where do I go from here?”

Eventually, Beck said she reported what was happening with Borek to Spencer, who urged her to keep quiet, promising he’d protect her. Under the guise of that protection, Beck said Spencer began to groom her.

He set up a private email for the two of them and would stay late with her if she had to work after hours. He invited Beck to dinner with his wife and kids and began referring to her as his little sister. He also secured raises for all the admissions counselors, Beck said, so she was able to quit her position with Borek.

Then, one night when they were both alone and working late, Spencer kissed her, she said.

“I think back on it now, and I wish I could tell that girl what was going on,” Beck told TRR. “But I remember being very confused at this point. How do you go from being siblings and feeling like you’re close to someone, and now he has these feelings for me?”

Beck said she felt “obligated” to Spencer and didn’t feel like she could say no when he “kept pushing those boundaries” and making sexual advances. “There was such an element of control,” she said. “. . . I had lost all power.”

In the spring of 1998, Beck said Spencer urged her to go with him to a Christian education conference in Las Vegas. Beck said she was scared and “pushed back hard,” but eventually conceded. During that trip, she became physically sick due to stress about the relationship, she told TRR.

That June, Beck decided to stay at Liberty until August to welcome students she had recruited to campus, then quit her job and return to her hometown in Washington state.

But earlier in August, a private investigator hired by Spencer’s wife discovered the sexual nature of Spencer’s relationship with Beck. Things moved quickly after that. Within a few hours, Spencer had alerted Beck to what had happened.

The senior Falwell called Beck, too, she said. “I recall him saying very vividly that he had been through this before with Jay,” Beck said. This made her angry, wondering why Spencer hadn’t been fired before, which would have spared her from the pain she was experiencing.

Beck said she wanted to leave town immediately, and Falwell said Liberty would take care of packing up the stuff in her apartment and making sure it was shipped to her.

Within 24 hours, Beck said someone—she guessed it was Spencer’s wife—was banging on the front door to her apartment.

“I just hid in my closet ’cause I didn’t know what was happening,” she told TRR. Beck said she felt like news of the scandal spread quickly , “so I hid in my closet until it got dark. And I just packed my car and drove home.”

Going up against ‘the good ole boys’

On the drive home, Beck said Falwell called her again, confirming Liberty would ship her belongings to her. She said he also informed her that Liberty had agreed to give Spencer $100,000 severance, though he said nothing of giving her one. Beck said Spencer also told her about the severance.

Falwell also said he would “reposition” Spencer at the American Association of Christian Counselors (AACC), Beck said. The AACC hired Spencer as VP of marketing and promotions the next year.

TRR reached out to Tim Clinton, who was the executive director of the AACC in 1999, with questions about Spencer’s hiring, but Clinton did not respond. Clinton currently serves as the executive director of Liberty’s Global Center for Mental Health, Addiction, and Recovery and is a professor emeritus.

By the time Beck reached her destination about 2,700 miles away, Falwell had stopped returning her calls, she said. Liberty then informed her that it would not pay the $6,000 it cost to ship her possessions to her.

So, Beck hired a lawyer. And in February 1999, she traveled to Richmond, Virginia, for mediation with the school.

“By this point, I weighed 91 pounds . . . I wasn’t eating. I was puking. I was not in a good place,” Beck said. “. . . I remember being so scared to walk into that room and have to sit across from (then-Liberty General Counsel) Jerry (Falwell), Jr., John Borek, Jay Spencer, and I’m pretty sure it was Mark Hine (executive vice president for student affairs).”

Beck said the judge for the mediation said as she walked in, “You do know you’re going against the good ole boys?”

Beck said she received a settlement, but is not at liberty to discuss the terms of the agreement. She says she destroyed the agreement years ago because it disgusted her. Although her attorney has since made multiple attempts to get a copy from Liberty, the school has not produced it.

Beck challenges Liberty University’s claim that there was an investigation into her allegations of sexual harassment at the time. She said no one from Liberty interviewed her—no administrator, lawyer, or outside party.

By telling her story, Beck said she’s hoping for a reckoning for Spencer and Borek and the Liberty leaders who covered up what they did to her.

At minimum, Beck said those who participated in her mediation should face consequences. Jerry Falwell, Jr., who became president of Liberty in 2007, resigned in the midst of his own sex scandal in 2020. However, Borek remains on Liberty’s board and Hine remains an executive vice president.

Liberty also claimed in its statement to TRR that “the late Chancellor Jerry Falwell, Sr. offered concern and support for (Beck’s) well-being multiple times. More recently, Chancellor Jonathan Falwell favorably responded when she reached out requesting a meeting with him.”

Beck said she now believes Jerry Falwell, Sr., was just trying to hurry her out of town when he called in August 1998, offering to help in the wake of Spencer’s scandal.

She said she reached out to Jonathan Falwell, Falwell, Sr.’s son, in 2023, requesting a meeting. Jonathan responded, she said, saying he remembered her situation and was open to meeting. Beck said she and Jonathan were able to agree to a meeting on a Friday. But when she tried to get details for that meeting, Jonathan failed to respond, similar to how his father ghosted her in 1998.

The next year, Jonathan attended the inauguration of Bluefield University President Steven Peterson, where Spencer spoke. And he and Liberty President Dondi Costin posed for pictures with Spencer and Peterson.

Beck also believes those who served as trustees in 1998/99 bear responsibility for what happened.

TRR spoke with Dwight “Ike” Reighard, one of the 16 current trustees who also served on the board in 1998. When asked about Spencer, Reighard said he didn’t know who he was.

TRR then asked if it was normal for the board to be kept in the dark when an administrator resigns for sexual misconduct, especially if it resulted in mediation and a settlement.

Reighard said that something that sensitive may have been handled exclusively by the executive committee.

According to an archived 1998 annual report, the executive committee at that time included nine members. Of those nine, only two remain on Liberty’s current board of trustees: Jerry Vines and John Borek. TRR reached out to Vines for comment about his knowledge of what happened with Borek and Spencer in 1998-1999, but he did not respond.

The chairman of the executive committee in 1998 was Mark DeMoss, whose now-shuttered public relations firm has handled some of the biggest names in evangelicalism when embroiled in scandals.

DeMoss told TRR he does not remember a severance deal for Spencer. He also said he doesn’t recall the name, Rachel Beck, or a settlement with her. DeMoss said that these kinds of issues “would generally not have come to the attention of the board or the exec. comm.” Instead, he said Borek likely “would have handled such matters out of his office.”

DeMoss added, “While I don’t know any details of allegations against Borek, he was relieved of his post at that time.”

However, Borek was never dismissed by Liberty. He resigned in 2004 and was awarded president emeritus status in 2005.

“I just wish someone would go in above the good ole boys and hold them accountable,” Beck said, adding she believes it’s a systemic problem and would like to see resignations from everyone involved. “Be accountable to each other. Be accountable to God. Be accountable to your wives, for Pete’s sake, and your family. And practice what you preach.”

*Correction: Tim Clinton has never served on Liberty University’s board of trustees as originally reported. This article has also been updated.