BOSTON (MA)

Encyclopædia Britannica [Chicago IL]

October 21, 2025

By Heidi Schlumpf

Top Questions

What have been the financial implications of the sexual abuse scandal for the Roman Catholic Church?

In the United States alone, between 2004 and 2023, the church spent more than $5 billion on cases involving sexual abuse by Roman Catholic clergy, and three-quarters of those payments went to victims. The church in Australia paid more than $200 million to victims from 1980 to 2017. Moreover, the scandal has led to a decline in church donations and attendance.

What was The Boston Globe’s Spotlight series on sexual abuse and the Roman Catholic Church?

In 2002 The Boston Globe’s Spotlight series exposed rampant sexual abuse by Roman Catholic clergy in the Boston archdiocese and a cover-up by church authorities. The series found that the archdiocese knowingly reassigned abusive priests to different parishes rather than removing them from the ministry. The scandal caused Boston to become a focal point for the abuse crisis in the United States and resulted in the resignation of Cardinal Bernard Law. In addition, it encouraged hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of victims to come forward globally, and it severely damaged the Catholic Church’s credibility.

Who was Father John Geoghan and what was he known for?

Father John Geoghan was a Boston priest and a notorious pedophile who symbolized the sexual abuse crisis in the Roman Catholic Church. He molested nearly 150 boys, and his crimes were detailed in The Boston Globe’s 2002 Spotlight series. Geoghan was ultimately defrocked, convicted of molesting a 10-year-old boy, and sentenced to prison. In 2003 he was murdered by a fellow inmate.

What is the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, and why was it created?

The Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People (also called the Dallas Charter) is a set of procedures and minimum standards approved by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2002 to address allegations of sexual abuse by Roman Catholic clergy. It includes training on prevention and reporting of sexual abuse and resulted in the creation of national and local diocesan review boards to oversee the handling of abuse allegations.

How did the Vatican respond to the Theodore McCarrick scandal?

In the wake of allegations that Cardinal Theodore McCarrick had sexually abused teenage boys and young men since the 1970s, Pope Francis ordered a Vatican investigation that led to the 2020 McCarrick Report, which revealed serious institutional failures. The report criticized Pope John Paul II for promoting McCarrick in the Roman Catholic Church’s hierarchy despite the allegations, and it led to reforms in reporting abuse by bishops.

*

After Patrick McSorley’s father died by suicide in the late 1980s, Father John Geoghan stopped by the 12-year-old boy’s home to express his condolences. The Boston priest offered to take him out for ice cream. Afterward, Geoghan sexually molested him in his car.

McSorley was one of nearly 150 victims of Geoghan, a notorious pedophile priest who came to symbolize the horrors of the clergy sexual abuse crisis in the Roman Catholic Church. His crimes were detailed in The Boston Globe’s 2002 Spotlight series and in the 2015 movie of the same name. Because of the Globe’s reporting, the archdiocese of Boston became ground zero for the abuse crisis in the United States. The series exposed not only rampant sexual abuse but also a cover-up by church authorities who knew of the allegations yet reassigned abusive clerics to other parishes. The magnitude of the crisis in Boston was appalling. Nearly a thousand children were molested by priests during a five-decade period, according to the archdiocese’s own report issued in February 2004.

But Boston was just the tip of the iceberg. Although reports of abuse had circulated in earlier decades, the Globe’s reporting gave hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of victims in the United States and globally the courage to come forward with their stories. The cost to the church—in legal fees, donations, and the trust of the faithful—has been incalculable.

The damage done

The sexual abuse crisis has severely damaged the Catholic Church’s credibility and permeates every aspect of life in the church today—even the election of a new pope. In May 2025, when Pope Leo XIV walked onto the balcony at St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City and was announced as the new leader of the global Catholic Church, a group of survivors of sexual abuse by priests, nuns, and others in the church issued an open letter to the first U.S.-born pontiff, urging him to take steps to move toward an “abuse-free church.”

The group, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), had six weeks earlier filed a complaint about Cardinal Robert Prevost (Leo’s pre-papal title and name) for mishandling two instances of sexual abuse by priests he oversaw before becoming pope: one in Chicago in 2000 and one in Peru in 2022. In the Chicago case, however, a lawyer representing victims admitted that Prevost might not have been informed of or involved in the abuse investigation. As for the Peru case, it is complicated by the involvement of a controversial lay movement that Prevost, as the bishop of the local diocese, had a role in suppressing, in part because of abuse allegations against the movement’s founder.

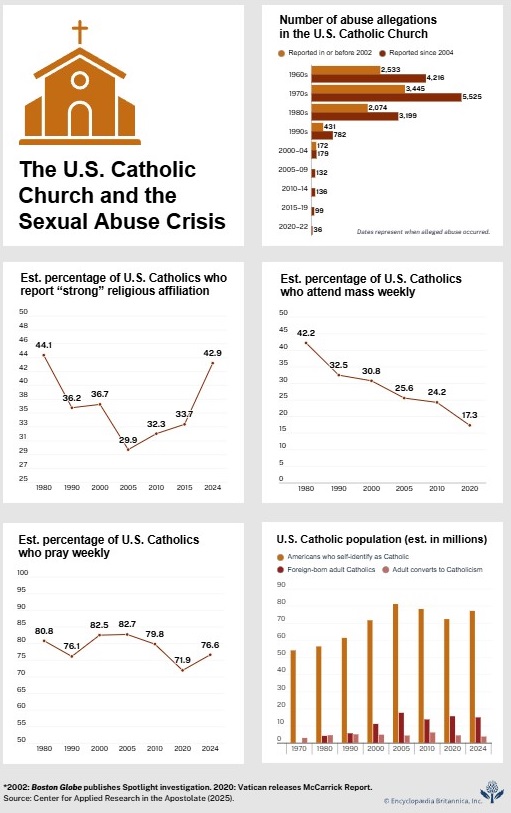

According to a 2025 Pew Research Center survey, a majority of Catholics in the United States see sexual abuse and misconduct as an ongoing problem in the church, even as the number of reported instances of abuse by priests and deacons has declined since the 1980s. According to a 2004 report commissioned by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and conducted by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, the number of allegations increased in the 1960s and peaked in the ’70s. Overall, the John Jay Report identified nearly 11,000 allegations against 4,392 priests—an estimated 4 percent of all priests—in the U.S. from 1950 to 2002. Very few of the alleged perpetrators were ever convicted.

For Catholics, and for those outside the church, the idea that some priests, nuns and other religious, and lay ministers and volunteers would use faith in God to groom victims for abuse, and then would rely on families’ and church leaders’ trust in the institution to evade punishment, is especially heinous. Although policies have been enacted to prevent abuse and encourage accountability, the decades-long history of abuse and cover-up still angers rank-and-file Catholics and casts a shadow on church leaders, not to mention haunting its victims.

Furthermore, the scandals have led to a persistent decline in church attendance in the United States, according to a 2015 study that examined 3,000 abuse allegations from 1980 to 2010. In addition, researchers in England found that a third of Catholics there who previously went to mass had reduced their attendance or stopped going altogether as a result of the abuse crisis.

A global crisis

Clergy sexual abuse is not just an American, or even a Western, problem. In 2014 the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child released a report condemning the Vatican’s response to sexual abuse of children by clergy across the globe. And the problem may be worse than has been documented. In some developing countries, where most of the world’s Catholics live, victims may be less likely to come forward, which makes data about the prevalence of abuse difficult to analyze.

Moreover, not all of the church’s abuse victims are children or laypeople. In Africa a report issued in 1998 found that nuns had been frequent targets of sexual harassment and rape by priests and bishops. In some cases, a religious sister became pregnant, and the offending priest insisted that she have an abortion, even though Catholic teaching condemns abortion during any stage of pregnancy.

In Ireland the government found nearly 2,400 allegations of abuse at schools run by religious orders between 1927 and 2013, and some Irish women have alleged that they were raped in so-called Magdalene laundries—former religious-run institutions for unwed mothers.

Lay movements in the church have also been home to sometimes widespread sexual abuse, especially among charismatic founders and leaders. Marcial Maciel, a Mexican priest who founded the Legion of Christ in 1941, sexually abused minors, including seminarians, and fathered multiple children. A close confidant of Pope John Paul II, Maciel evaded repercussions until the Vatican, under Pope Benedict XVI, ordered him to retire to a life of prayer and penance in 2006. The Legion did not acknowledge his abuse until after his death in 2008. The order’s website now includes the statement that “we do not consider him a role model due to the gravity of his actions.”

Australian Cardinal George Pell was the most senior Catholic cleric to be convicted of child sexual abuse, in 2018, although his convictions for molesting two 13-year-old choirboys were overturned on appeal. Pell died in January 2023.

Jean Vanier, a Swiss-born Canadian lay activist and theologian who founded the well-respected L’Arche movement, which provides homes for people with developmental disabilities, was determined, after his death in 2019, to have abused at least six women in France between 1970 and 2005.

The abuse crisis in the United States

In the United States the abuse crisis became a concern for some Catholics when two newspapers broke the story of clergy abuse. In 1985 the National Catholic Reporter (NCR) and the Times of Acadiana in Louisiana copublished a series of articles about Father Gilbert (Gil) Gauthe, a serial pedophile who eventually went to prison for his crimes. “The story was not one man who happened to be a priest with a terrible criminal pathology,” Jason Berry, the freelance journalist who wrote the pieces, told NCR in 2025. “It was really the story of a cover-up.”

Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago was among the first church leaders to confront the issue of sexual abuse by clergy, creating a victim assistance ministry in 1992. The following year Bernardin was publicly accused of abuse by a former Cincinnati seminarian, who claimed that he had recovered repressed memories of being molested by Bernardin as a teenager, but in 1994 he withdrew the charge. One of the first public accusations against a cleric in the United States, the case brought attention to the reliability of such recollections which, because of the complexity of human memory, are often difficult or impossible to corroborate. However, shortly after recanting his accusation, the former seminarian reached an out-of-court settlement with the Cincinnati archdiocese in a lawsuit involving abuse by another priest.

The year 2002 was pivotal in bringing attention to the issue of abuse and cover-up with The Boston Globe Spotlight team’s exposé of Geoghan and other priests who had been shuttled from parish to parish, even after officials at the Boston archdiocese knew of their abuse of children. The movie Spotlight (2015) won the Academy Award for best picture in 2016, which drew even more attention to the scandal. The Boston revelations were instrumental in bringing the issue to the attention of everyday Catholics in the pews. The Spotlight series led to the resignation of Boston Cardinal Bernard Law, to the emergence of lay advocacy groups, such as Voice of the Faithful, and eventually to changes in the church’s approach to abuse cases.

Boston also became a symbol of the financial costs—and often of injustice toward victims—in settlements of abuse lawsuits. After initially agreeing to a $30 million deal with 86 victims, including McSorley, the archdiocese reneged, and the victims ultimately accepted $10 million. In 2004, Boston clergy abuse survivor William Oberle told The New York Times, “The money’s nothing. It doesn’t bring closure.” Geoghan, meanwhile, was removed from the priesthood, found guilty in 2002 of molesting a 10-year-old boy, and sentenced to prison, where he was murdered by a fellow inmate a year later. The tragedy did not end with his death. McSorley became an outspoken voice for survivors, but he struggled with alcohol and drug addiction and died in 2004 at the age of 29. After McSorley’s death Oberle told the Times, “I said when Geoghan died, at least he’ll never molest another child again. But he’s still molesting them. He’s still affecting these children.”

In response to the firestorm after the Boston Globe exposés, in 2002 the USCCB, at the time led by Bishop Wilton Gregory, approved a set of procedures and minimum standards to address allegations of sexual abuse by clergy. The Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People required training on prevention and reporting of child sexual abuse, and its zero-tolerance policy mandated reporting allegations to authorities and suspending the accused during investigation. The document—known as the Dallas Charter for the city where the USCCB’s annual meeting took place that year—also created a national office and review board and local diocesan review boards to oversee the handling of abuse allegations.

The Dallas Charter has been updated periodically throughout its history, but it has been criticized for failing to address the problem of bishops who have been accused of abuse or who were complicit in abuse cover-ups. This became apparent in the summer of 2018 when news about Cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s abuse of seminarians became public after decades of rumors and attempts to bring his behavior to the attention of church officials, including Pope John Paul II. The once-powerful archbishop of Washington, D.C., McCarrick was removed from ministry and eventually from the priesthood for multiple instances of assaulting children and adults. He became the highest-ranking cleric in the United States to face criminal charges for sexual abuse, although cases against him in Massachusetts and Wisconsin were dismissed because he had developed dementia. He died in April 2025.

Also in 2018, just weeks after the McCarrick revelations, the attorney general of Pennsylvania released a grand jury report that summarized a two-year investigation into the history of sexual abuse in six of the state’s eight dioceses. The report identified more than 300 priests accused of abuse over a 70-year period, although only 2 had been involved in abuse since 2008. When the grand jury’s report was combined with data from the other two Pennsylvania dioceses, it showed that about 8 percent of priests had been accused, nearly double the percentage found by the John Jay study in 2004. The Pennsylvania report prompted other states, including Illinois and Maryland, to conduct similar investigations.

The Vatican’s response to the crisis

In response to the McCarrick scandal, Pope Francis ordered a Vatican investigation, which revealed institutional failures at the highest levels—failures that had led to repeated promotions of McCarrick despite rumors of his alleged sexual misconduct as early as the 1970s. In the 461-page McCarrick Report, released in 2020, much of the blame fell on Pope John Paul II (who died in 2005 and had since been canonized as a saint). John Paul had appointed McCarrick archbishop of Washington and made him a cardinal in 2001 despite being warned in 1999 by New York City’s Cardinal John Joseph O’Connor that McCarrick was known to invite seminarians to sleep with him at a summer cottage.

According to the McCarrick Report, Pope Benedict XVI had also failed to formally investigate him, but he had accepted McCarrick’s resignation as archbishop of Washington at the customary retirement age of 75 and given him informal instructions to maintain a lower profile. Although Benedict is remembered for some of his abuse reforms when he served as head of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) and, later, as pope—including removing nearly 1,000 abusive priests from their ministry—he was also criticized as being initially slow to recognize the magnitude of the crisis.

Pope Francis’s tenure was punctuated by attempts to respond pastorally to the crisis but also by missteps that would lead some commentators to call his legacy on the issue a mixed one upon his death in April 2025. In 2014, for example, one year after Francis was elected to the papacy, he established a first-of-its-kind Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, headed by Cardinal Seán O’Malley of Boston. The group, however, was beset with controversy, and several prominent members resigned in frustration at its inability to enact policy recommendations. During a visit to Chile in 2018 Francis defended a bishop accused of covering up for a notorious abuser, but he seemed to have a change of heart and later met with victims and apologized.

In February 2019, in the aftermath of the McCarrick allegations, Francis called a Vatican-level summit on abuse. That same year he released the apostolic letter Vos estis lux mundi (“You Are the Light of the World”), which established a new global system that filled the gaps for investigating bishops accused of abuse or cover-ups. The legislation was updated and made permanent in 2023.

Financial fallout and lasting trauma

Although it is impossible to put a number to the cost of the sexual abuse scandal on the Catholic Church, the financial damage has been considerable. In the United States alone more than $5 billion was spent between 2004 and 2023, according to a report from the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University. Three-quarters of those payments went to victims. The church in Australia paid more than $200 million to victims of sexual abuse from 1980 to 2017.

These figures, as sobering as they are, do not even include the decline in donations, credibility, and church affiliation and attendance over the decades or the effect on victims’ mental health and lives. Studies have found an increased risk of suicide among victims of childhood sexual abuse, and others have spoken of abuse as causing a “moral injury” of psychological, emotional, spiritual, religious, moral, and relational trauma.

But victims often refer to themselves as “survivors,” and some say that speaking out has given them some peace. “I want anyone out there who’s had to go through this to do something about it, because you’re not alone and there’s a lot of people that will help,” Linda Carroll said in 2014 when she filed a lawsuit 45 years after she was abused as a second-grader by Father James Porter, a notorious abuser in Minnesota who claimed to have molested 100 children over three decades. Carroll added, “I’ve suffered from depression my whole life, and I’m done—not standing in the shadows and not ashamed and not going away.”

Heidi Schlumpf is an award-winning journalist and podcaster with three decades of experience covering religion, spirituality, as well as political, social, and women’s issues. She spent 16 years with National Catholic Reporter as a columnist, correspondent, and executive editor/vice president. She previously served as managing editor of U.S. Catholic magazine and a reporter at Chicago’s archdiocesan newspaper. Her work has appeared in Mother Jones, CNN Opinion, Religion News Service, Commonweal, and Sojourners.

Schlumpf has been a cohost of the Francis Effect podcast for five years. She also is a part-time faculty member in theology at Loyola University Chicago. She previously taught journalism as an associate professor of communication at Aurora University in Chicago.

A graduate of the University of Notre Dame, she also earned a master’s of theological studies from Garrett Evangelical Theological Seminary at Northwestern University, where she studied with feminist theologian Rosemary Radford Ruether.

She is the author/editor of Elizabeth A. Johnson: Questing for God (2016), the Notre Dame Book of Prayer (2010), and While We Wait: Spiritual & Practical Advice for Those Trying to Adopt (2009).