VATICAN CITY (VATICAN CITY)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

October 27, 2025

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

Early this month, Tutela Minorum published its second annual report on clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church at a global scale.

Soon after, Pope Leo XIV met with ECA, a global NGO supporting victims and survivors of clergy sexual abuse.

Despite the goodwill, minor but noticeable mistakes in handling the meeting soured the perception of Leo XIV’s and his curia’s commitment to addressing sexual abuse.

Early in October, Tutela Minorum, the entity created by Pope Francis back in 2014 to prevent clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church officially published its second annual report on the state of the issue behind its very existence.

Soon after the publication of the report, on Monday October 20, Leo XIV met with Ending Clergy Abuse, a global NGO supporting victims and survivors of clergy sexual abuse.

Although there was goodwill in the meeting and in what Vatican News and other Catholic media published about the meeting, it was impossible to miss how the Vatican bureaucracy dealt with the meeting as such. More details on this issue will come by the end of this piece.

The Executive Summary of the report appears as a PDF in the box after this paragraph, and the full report is available for download here, at the website of what officially is the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors known, for short, as Tutela Minorum or simply Tutela.

Their mandate is rather narrow. When Pope Francis created it, through a so-called chirograph, available here, he set it up as “an advisory body at the service of the Holy Father,” with its own, separate, headquarters, website, social media, patrimony, and “public juridic personality.”

Despite those features, it is not a powerful institution in the Catholic Church as it fell under the purview of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, and it lacked the necessary means to achieve its rather modest goals. Its authority, if any, is moral, and only to advise the Pope and whoever wishes to pay attention to what its members say at any given point.

To put it simply, Tutela cannot order a priest in any parish of the Catholic world to actually stop abusing another person. That frailty is in stark contrast with the scale of the crisis as such and with the fact that aligned with Vatican tradition, the creation of the Commission was charged from the outset with oversized expectations. That and the lack of effective power to solve any of the issues shaping the clergy sexual abuse crisis, ultimately came back to undermine it.

It is impossible to go over the many issues Tutela faced in its first four or five years, Suffice it to say at this point that some of its original members, most notably Irish clergy sexual abuse survivor Mary Collins, left the commission.

Collins did it three years after her original appointment in 2014. She did so, criticizing the Roman curia’s unwillingness to fund Tutela’s work and to grant access to information about the issue they were dealing with.

Scandal after failure

After the initial failure to properly fund it, a scandal marred what was a sort of relaunching of the entity in 2021. It involved its now emeritus secretary, Andrew Small, an Oblate of Mary Immaculate priest who used to be the United States Catholic Bishops Conference liaison with the corresponding national conferences of bishops in Latin America.

An expert in finances, confronted with the need to find funding, Small used his access to other funds in the Catholic Church to get the money required to turn Tutela from a label into an entity able to pay a small payroll and develop some regular activities. That turned him and another former official of the entity, Jesuit priest Hans Zollner, into the main characters of a bitter public argument.

So, despite what seemed to be Francis’s best efforts as to render Tutela’s creation as a step in the right direction, more than ten years after that decision, its failures are, by far, more notable than whatever success it could have achieved so far.

That remains a fact even if it has a budget now, it owns a small palace in Rome from where it can conduct its own business, now under a new leader, since Cardinal Seán O’Malley was replaced as president of the commission by French archbishop Thibault Verny, back in July. A previous installment of this series, linked after this paragraph, went into more details as to who is Verny.

The idea of publishing yearly reports on how the Church deals with sexual abuse was a rather late development in the evolution of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, and it took almost eight years for Pope Francis to figure out it would be a good way to begin a healthier understanding of the issue.

Low-quality data

As good as the idea is, however, their first report was, for the most part, the byproduct of rather low-quality, self-reported data provided to them by the conferences of Catholic bishops. In that regard, it is almost impossible to see it as an exercise on transparency or accountability.

Last year, when going over the first report, in a previous installment of this series (see the story after this paragraph) it was impossible to agree with what that report stated of an alleged full compliance based on data previously provided by the Mexican Conference on Catholic Bishops (CEM after its Spanish acronym) with Pope Francis’s policies.

The Catholic Church’s report on clergy sexual abuse

A few months before the publication of the first report, a previous installment of this series found that, less than half the 96 Mexican Catholic dioceses of Roman Rite (there are three of Oriental Rite, see here or here), had actually complied with Pope Francis’s most significant policy request: creating at least one commission to prevent clergy sexual abuse in each diocese, as the story linked after this paragraph details.

Less than half the Mexican Catholic dioceses prevent sexual abuse

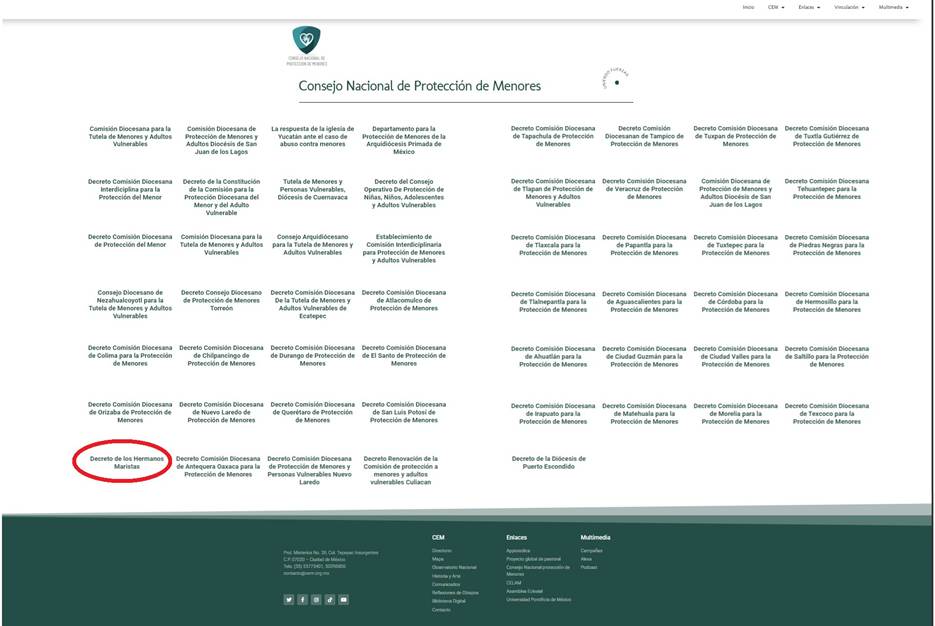

Up until today, Saturday October 25, 2025, if one goes to the CEM’s website it is possible to find a small improvement, but still no evidence to claim, as Tutela’s first report did, that the Mexican bishops are in full compliance.

The screenshot taken from their website (original available here, but only in Spanish) proves that, so far, only 53 commissions are listed and of those one was created by the Mexican province of the Marist Brothers, so, only 52 actually belong to the Mexican dioceses.

Against the 96 dioceses, the compliance rate thus stands at just over 54 percent, eight more commissions since the report published by this series in April 2024, as the story linked before this paragraph proves. So, from “less than half” now CEM stands at “little more than half” the total number of dioceses.

The only other improvement one finds at the Mexican bishops’ website is its design. Beyond that, it is really hard to believe that preventing clergy sexual abuse, even if only of minors is a priority for CEM. And that is without going into the issue of how each diocese claims to reach the alleged goal of safeguarding.

There are dioceses in Mexico where the local commission only integrates its own priests, most of them have some laypersons playing a role, but in some cases it is hard to figure out if the laypersons are actually such, or if they belong to Regnum Christi, Opus Dei or some other “new movement,” whose members are not technically friars or nuns of a religious order but who, in practice, lack the independence from the diocese required to actually prevent clergy sexual abuse.

What was clear a year ago, when going over Tutela’s inconsistent assessment of the Mexican case was that the Commission was misled by a mechanism that leaves its methodology vulnerable to misreporting by the bishops themselves, whether they are from Mexico or elsewhere. And what is worse, this year’s report does not offer a reassessment of what they said about Mexico in 2024.

As far as the report published this year, Tutela’s document claims to be “anchored in the framework of Conversional Justice, with a specific focus on reparation for victims/survivors.”

Conversional justice is Tutela’s take on the issue. For them, this notion of justice depends on four pillars: truth, justice, reparation, and institutional reform (see pages 25-31 of the report).

In doing so, one finds an attempt to broaden the scope of Tutela’s authority and mandate, which could be good for the issue, if it is actually supported by a thorough understanding of what reparations entail and if Tutela is able to convince the conferences of bishops, the bishops, and the Catholic laypersons to actually follow some of its recommendations.

Main problem there is that one can find how, in social media, there are active efforts from priests and laypersons challenging the very idea of the existence of a global crisis of clergy sexual abuse while trying to discredit whoever dares to share content furthering that notion.

Also, as much as Tutela’s report highlight the need for the Church to actively engage with this notion of “conversional justice,” the very lack of data about the extent of the crisis makes very hard to believe that the Catholic Church’s hierarchy is actually willing to develop such model of “conversional justice” to address the clergy sexual abuse.

Streamlined protocol?

One only needs to see how, at least in two pages of the report (9 and 16), its authors talk about the need to develop a “streamlined protocol for the resignation and/or removal of Church leaders or personnel in cases of abuse or negligence” and compare to what is currently happening in two countries with long-standing traditions of Catholic practice and how they deal with the issue of the “early” resignations of bishops accused of either being predators or of covering up for predator clergy.

In Peru, where Leo XIV cut his teeth as bishop, and already with him as Pope, there was a few weeks ago the report of the “early” resignation of a bishop who engaged in abuse of his religious leadership with at least ten females in his diocese.

Three weeks ago, the Post-Data section of the story available after this paragraph went over the case of Ciro Quispe López’s resignation, at 52, as bishop of Juli, Peru.

Latin American Catholics lose trust, is sexual abuse the culprit?

There one finds a story all too familiar with whoever has followed even from a distance the 40-years-long clergy sexual abuse crisis knows that something very bad should happen when Rome forces out a bishop in his early 50s.

Despite that consciousness of the reasons behind “early resignations” such as that of Quispe López, as with many other “young” emeritus bishops there is no official information as to the reasons why they were forced out of office.

The Holy See’s Bollettino for September 24, 2025, simply stated in one sentence: “The Holy Father has accepted the resignation from the pastoral care of the territorial prelature of Juli, Peru, presented by bishop Ciro Quispe López.”

Some of the Conservative Catholic media attacking Francis during his tenure as Pope, rekindled their attacks on the Argentine Pontiff using Quispe López’s case as an excuse, but with little or no actual interest in the fate of the bishop’s victims.

One had to go to local Peruvian media, sources such as Hildebrandt, the weekly magazine, to learn that Quispe López was a rather promiscuous “celibate”, one who on top of being very sexually active, was more than willing to use easy-to-hack apps such as Whatsapp to set up sexual encounters with his many partners.

Quispe López’s case offered an excellent chance to be transparent about the real reasons for sending into early retirement someone who will not only retain the salaries the Peruvian government is willing to pay the Catholic bishops, but who will also retain the title of “emeritus bishop”, free to preside over sacraments and rituals with the sole exception, perhaps, of ordinations.

After Hildebrandt’s piece it would be hard to find a Peruvian, Catholic or not, willing to believe the old tale about “health reasons”, as Quispe López’s predecessor there claimed when Francis forced him out of office.

Outside of Peru, in the English-speaking world, African newspapers were very willing to broadcast the news about Quispe López’s exist from Juli. Moreover, after Hildebrandt’s early revelation, the scale of the abuse increased significantly, with a report published in Ghana claiming the bishop was accused of having 17 “secret” sexual partners.

Despite that, for whatever reason, Rome decided to process Quispe López’s case with the same opacity that many cases of bishops’ “early” resignations have been managed since the clergy sexual abuse crisis emerged back in the early 1980s.

Catholic bishops forced to resign, looks can be deceiving

Back in 2023, this series published the installment linked before this paragraph dealing with the overall number of bishops forced to resign over the last four decades before reaching the usual 75-year-old mark. So, there is a real need to actually inform about the real reasons behind such “early” resignations”.

Early this year, the series set at 30 the total number of bishops Pope Francis had forced out of office in 2023 and 2024, linked after this paragraph.

Pope Francis forces out of office 30 bishops in two years

It must be noted, however, that with Quispe López, the “early” character of his resignation is valid only when considering his age. In any other respect, he wasted his and his flock’s time by remaining bishop for the little less than seven years he was the head of the diocese of Juli.

France, once again

More recently, on Thursday, October 23, French media published stories about Jean-Michel Alain di Falco Léandri. He is one month shy of 84, and yet, he is still making headlines after Mediapart (content in French and behind a paywall), a digital French medium published a report on his “equivocal relationship,” with who used to be an underage male.

The evidence of Di Falco’s “equivocal relationship” comes from 130 letters (contents in French) he wrote to Aurélien from 1987, when he was 15-year-old, until 1993.

Moreover, Di Falco was writing said letters while moving from being a priest in the archdiocese of Marseille, in Southern France to Paris, where he was appointed as the spokesman of the French Conference of Catholic Bishops, then headed by Albert Decourtray, the archbishop of Lyon.

Di Falco held that position for little over nine years, until 1996. Next year, Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger, then archbishop of Paris and a powerful figure in John Paul II’s curia, promoted Di Falco to auxiliary bishop of his diocese in 1997.

At the French capital Di Falco would be in charge of the project to launch KTO, the French national Catholic TV network. His work there, gave him a chance to become a major player in other Catholic entities dealing with the media, including the now defunct Pontifical Council for Social Communications, now Dicastery for the Communications.

Di Falco remained an auxiliary bishop in the French capital until 2003. That year, in a rather odd move, he became the auxiliary bishop of Gap, a suffragan diocese of Marseille, taking over two months after his appointment as auxiliary. That happened when then bishop Georges Lagrange resigned little more than a year before reaching 75.

Main problem now for emeritus bishop Di Falco is that, early this year, Aurélien decided to end, at 53, his life. When that happened, the details of Di Falco’s letters to Aurélien became available for the French media.

If that was not enough, before the letters became public in Mediapart, Libération, the French daily newspaper published back in July information about Di Falco being a person of interest in a probe where Di Falco is accused of spiritual abuse of a nonagenarian who died in 2013. Somehow, Di Falco became the heir of his 17 million Euros fortune, despite being unrelated to each other.

On top of the letters he wrote to Aurélien, already during his tenure as auxiliary bishop of Paris, in 2001 and 2002, Di Falco was facing accusations of sexual assault, when he was a young priest in the 1970s (contents in French). He benefited from the statute of limitations in both cases, so Di Falco was able to remain in office.

Both accusations did nothing to derail his appointment as bishop of Gap, a small town, 92 miles or 148 kilometers North of Marseille.

So, whether one looks at Juli, Peru or at Gap, France, there is an actual need to improve the vetting of future bishops, but also to inform about why some of them are able to keep getting promotions despite accusations or about the real reason behind early “resignations.”

This year’s report

This year’s Tutela report adds some external context to the assessment. For each of the countries it covers, a total of 22, it acknowledges the information offered by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. It is unclear how much the Catholic bishops actually trust such source, as it is, as many other commissions and committees of the United Nations’ system, the target of criticism for the adoption of what the most conservative Catholic bishops have construed as one of their existential enemies: the so-called “gender ideology.”

Despite the implicit tension there, it is noticeable that this year report adds that element to the overall assessment Tutela does of what the Catholic Church does to prevent abuse in each of the countries considered.

It would be impossible to go over each of the 22 countries and two religious orders considered in this year’s report, the male-only Brothers of Christian Instruction of St. Gabriel, the so-called Monfortains, and the female-only Missionary sisters of Our Lady of Africa.

Overall, the report seems to indicate that at least Tutela is aware of major issues. Among the most notable at a global scale, what it calls “the partial and often insufficient role of financial compensation for victims.

That is why, most of this section will be centered on what it says about the measures taken so far by the Italian and Portuguese conferences of Catholic bishops.

As much as the report contains valuable insights about the plight of victims and survivors and makes repeated calls for the hierarchy of the Church to acknowledge the need for change, it is hard to understand why Tutela decided to call “focus group” what are, by their own description listening sessions with individual victims.

Tutela states in p. 32 of the report what follows:

- First, while the term used is “focus group”, the methodology involves individual listening sessions with victims/survivors, who do not interact with each other. Second, this focus group does not constitute a form of social science research. Nor is it a form of therapy, although the Commission certainly acknowledges the importance of such, and the focus group methodology includes steps to avoid harm given the vulnerability of victims/survivors. Finally, the focus group does not replace other forms of ongoing engagement with victims/survivors, and thus is not designed to constitute the only or even primary form of the Commission’s engagement with victims/survivors.

There is no additional explanation of why they decided to identify what they did, which is useful, with a concept used by the social sciences to gather information by assembling small groups of individuals sharing some common traits (age, gender, national origin or ethnic background, income, and education, the most common).

Had the section be called “Victim/survivor profiles” or “experiences” or “accounts” it would be as useful as the current section starting on page 32, without forcing the reader of the report to try to understand what is the upside of calling “focus groups” what the report openly admits are not actually focus groups or, even worse, why using that notion of “focus groups” to label their own strategy of information gathering?

It is some kind of odd “cultural appropriation”? Is it an attempt to bring more confusion to the Church’s handling of clergy sexual abuse?

If so, then Tutela Minorum is actually achieving something there although it is impossible to understand what that could be. More so, when one goes over what scholars who have been using, testing, improving, and crediting this methodology for more than 40 years now have been publishing, as summarized in this piece from the Sage Research Methods Community.

It would be perfectly valid for Tutela to offer their findings, labeling them as “individual interviews,” instead of calling them “focus groups” while acknowledging their method, whatever it is, has nothing to with the current standard understanding of what focus groups are.

This suggests either a lack of technical understanding of standard research methods or a deliberate attempt to borrow academic language without adhering to its requirements. And what is worse, in doing so, this entity of the Catholic Church only hurts itself.

The Italian case

Putting these and other issues aside, the section dealing with the Italian Conference of Bishops (content in Italian), or CEI after its Italian acronym) in the report is major. Mostly because, there are some major reports dealing with clergy sexual abuse in Catholic settings in France, Germany, Ireland, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

There was, at some point during the pandemic, a report from Portugal, but as Tutela’s report acknowledges that report has been taken out of circulation with no signal as to when the Portuguese bishops will be willing to make it available again. In that regard, of the most populous European countries with large Catholic populations, the only two missing are precisely Italy and Portugal.

There is no way to compare what Tutela did with Italy in this report with what the Sauvé Report is in France, but at least what Tutela puts in black and white at this point offers a more precise glimpse at the state of the issue in Italy.

The report is the result of meetings with several regional delegations and the answers given to questionnaires sent by Tutela. Despite the dismal responses, a positive aspect of what Tutela did in Italy is the possibility of expanding this model to other countries, where it is counter-productive to rely only on the national conference of bishops as the sole source of information.

Even if Tutela acknowledges a proliferation of diocesan offices and listening centers for reporting and assistance reflecting a certain acknowledgment of the scale of the crisis there, it also highlights “inconsistent resources and staffing” and disparities in the personnel and resources available.

Tutela warns about how many of the offices lack “stable and sufficient staff and financial resources,” while others are only active “when needed”. Similarly, Tutela stresses the absence of a “centralized office” to handle the reports and the delivery of the expected services.

Besides this logistic and financial issues, the report stresses the role of “cultural resistance” including a notable feature of global Catholic culture: silence. This is relevant, among other reasons for the role it plays in reinforcing cultural taboos associated to Catholic clericalism.

Tutela‘s report acknowledges the role said culture of silence plays as a roadblock to discuss abuse, making it difficult for victims to even talk with their families about abuse, and even harder to report it to authorities.

It also plays a role in the difficulty the Catholic Church has to actually dialogue with victims/survivors, their relatives and advocates.

Adherence to a culture of silence, where the priest is still perceived as deserving special treatment, leads to what the report identifies as “poor dialogue with victims.”

Story of Lisbon

As far as the Portuguese Episcopal Conference, CEP after its Portuguese-language acronym, the report follows a similar path although CEP was actually willing to commission a less ambitious report on sexual abuse it offered a different take from the criminological approach followed by the USCCB 2002-4 pioneering report commission to the John Jay College of Criminal Law.

It was also different from the French Sauvé Report, building its knowledge over the foundation of an extremely large sample poll with enough cases to be representative of each municipality in France.

The Portuguese report followed a more psychoanalytical approach. Originally, it was published in both Portuguese and English and was hosted on its own website.

Someone in Lisbon was not pleased with the findings, which confirmed, from a different perspective what other studies had said about clergy sexual abuse, so the report disappeared and these days it is only possible to find, if anything, the Executive Summary in Portuguese.

So, no surprise when reading over p. 94 how displeased are the authors of Tutela’s report with what they call the “inaccessibility of the full report.” The report stresses how, currently, the only publicly available document is the Executive Summary.

Following the line of criticism used when addressing the Italian case, the commission expresses its concern with what they call the “lack of clarity on victim support.” As many other conferences of bishops worldwide, the Portuguese bishops offer some “therapeutic services” through the so-called Grupo VITA (opens content in Portuguese).

That group has been the target of criticism in the Portuguese-speaking world for the lack of transparency of their ties to the Catholic Church in Portugal. Even in their own website they acknowledge the fact that they lack a “stated goal,” and yet they play a rather prominent role in shaping the way the Catholic Church deals with clergy sexual abuse there.

They claim close “collaboration with the National Coordinating Team of Diocesan Commissions, those commissions, the institutes of consecrated life, the societies of apostolic life and other church structures,” without actually stating what is its own canonical or civil status in its website.

It should not surprise how, when dealing with the Portuguese case, Tutela is warning about the existence of what it calls “transparency and information gaps,” including but not limited to the “lack of clarity regarding the budget and sustainability of safeguarding formation.”

And the same could be said about the absence of an effective “audit mechanism” to evaluate the local Church’s safeguarding policies, practices, and claims. What exists is Grupo VITA claiming to be close but not dependent on the Portuguese conference of bishops, and that is it.

The report also highlights the “lack of clarity regarding the relationship and cooperation with the Conference of Religious and the Conference of Secular Institutes.” In other words, there are difficulties when bishops and superiors of religious orders have to deal with cases of clergy sexual abuse, and usually the effects of such difficulties affect the victims, not the dioceses or the orders.

Overall, there are 13 “critical recommendations” to CEP, emphasizing a continued need for transparency and a victim-centered approach.

Finally, it should be noted that Both the media and the victims’ advocates in Italy and Portugal agree with the report’s findings. They see the report as an official validation of sorts of their long-standing complaints of negligence and institutional cover-up by the local bishops.

Meeting with ECA

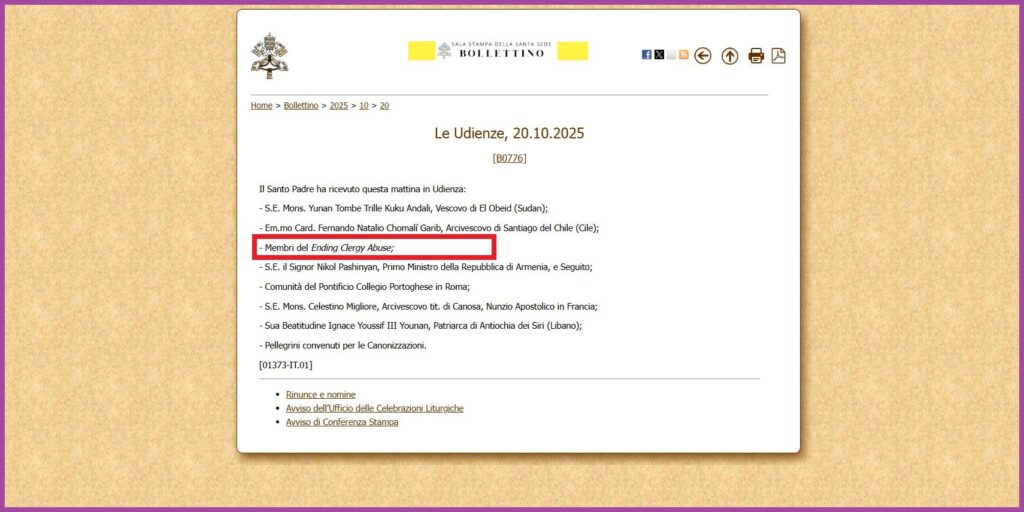

Soon after the publication of the report, on Monday October 20, Pope Leo XIV met with members of Ending Clergy Abuse, ECA, a leading global survivor NGO. Usually, that kind of meetings are reported by the so-called Bollettino. Back in the late 20th century, it was an actual bulletin, printed in paper, later sent over telex or fax to the media registered at the Sala Stampa of the Holy See.

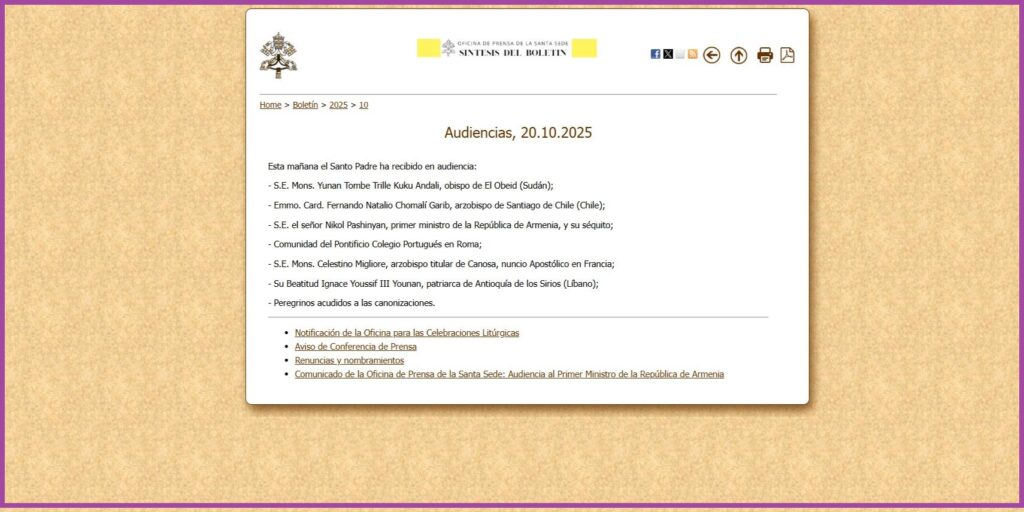

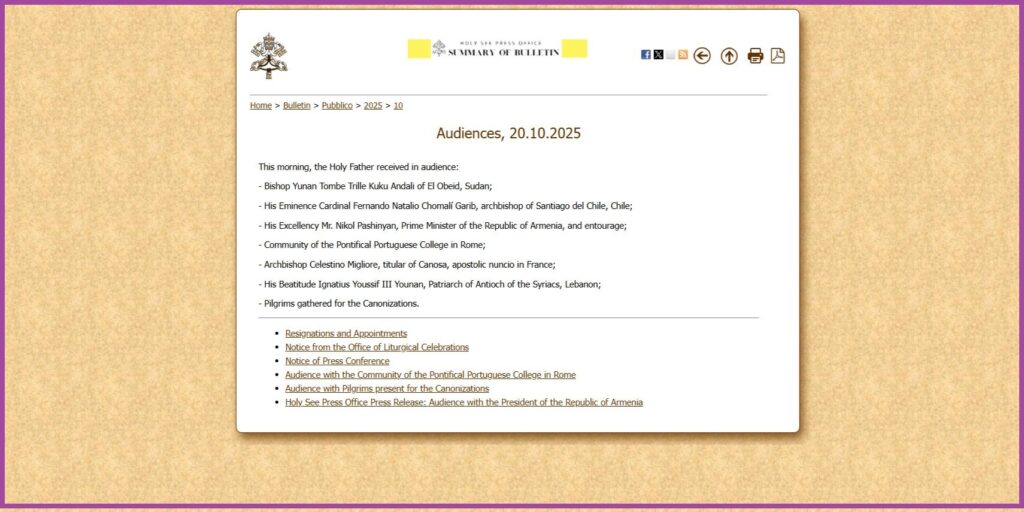

These days, the Bollettino exists as a trilingual edition, Italian, English, and Spanish, at the Vatican’s main website.

Usually, the three versions of the Bollettino mirror each other, so the information is the same in each of them. Some days, however, things do not go so smoothly. Oddly enough, Monday October 20, 2025, the day Leo XIV met with ECA, after meeting with one of Chile’s staunchest defenders of sexual predators, the archbishop of Santiago and Cardinal, Fernando Natalio Chomalí Garib, was one of those days.

Even if minor, the mistake is reminiscent of how, back in the 1990s, John Paul II and his curia would do their best to pretend that abuse was only an issue to be concerned with in the English-speaking world, so whatever was said about abuse in those days was available only in English.

It is almost impossible to try to figure out why the differences in the three versions of the Bollettino, Ending Clergy Abuse did its best to not make an issue out of the discrepancy, and its leaders shared over social media the expectation of having a productive relationship with Pope Leo XIV after the meeting.

Up until Saturday October 25, the discrepancy remained as can be seen in the screenshots in Italian, above this paragraph, where one finds the reference to Ending Clergy Abuse, but that does not happen neither in English nor in Spanish, as the screenshots after this paragraph prove.

One of ECA’s leaders is Matthias Katsch, a German survivor of clergy sexual abuse, he presides Eckiger Tisch in his country, and back in August, he published with Los Angeles Press a piece, linked after this paragraph, summarizing his experience on how to address clergy sexual abuse in Germany.

Stories that matter, how to reappraise sexual abuse

This discrepancy in the Vatican’s official medium was noted by the press, as it stood in contrast to the meeting’s significance—it was the first time Pope Leo XIV had met with an organized, global activist group of survivors. The delay and lack of immediate, multi-language confirmation in the official record were widely interpreted as reflecting the ongoing internal tension and institutional resistance within the Vatican that Tutela Minorum’s report criticizes.

After the meeting, ECA issued a statement and held a press conference where they praised the meeting as a “deeply meaningful conversation” reflecting a “shared commitment to justice, healing and real change.”

ECA framed their approach as that of “bridge-builders, ready to walk together toward truth, justice and healing,” indicating their aim at collaborating with Leo XIV centering on the need for actual Universal Zero Tolerance.

ECA shared their Zero-Tolerance Initiative, emphasizing the urgent need for consistent global standards where any credible accusation of abuse results in a permanent removal from ministry. Co-founder Tim Law noted that the Pope was sympathetic but acknowledged “there is great resistance” to make that happen. Their full statement is available here.

Katsch saw the Pope as willing to “help heal child sexual abuse in the Church,” but added realistically, “the times where a pope is saying one sentence, and everything is settled are over.”

Later, by Friday October 24, Matthias Katsch published this over his Facebook account, availabe after this paragraph or, if not in full display, also here:

Monday was a historic moment: for the first time, a Pope received not individual victims/survivors but an alliance of affected and activists. This has a new quality.

Together with Sergio Salinas, Evelyn Korkmaz, Janet Aguti, Timothy Law, and Gemma Hickey from Ending Clergy Abuse (ECA), we met with the Pope for the first time.

In the private audience with Pope Leo XIV, we spoke openly about what has moved so many of us for decades: justice for those affected, the implementation of a Zero-Tolerance policy, adequate compensation, and genuine protection for children and adults in need.

Since its founding, Ending Clergy Abuse has consistently advocated for the creation of independent accountability mechanisms, the promotion of access to ecclesiastical archives as part of the healing and reparation process, and the inclusion of survivors in reform efforts.

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez