NEW ORLEANS (LA)

National Catholic Reporter [Kansas City MO]

December 18, 2025

By Jason Berry

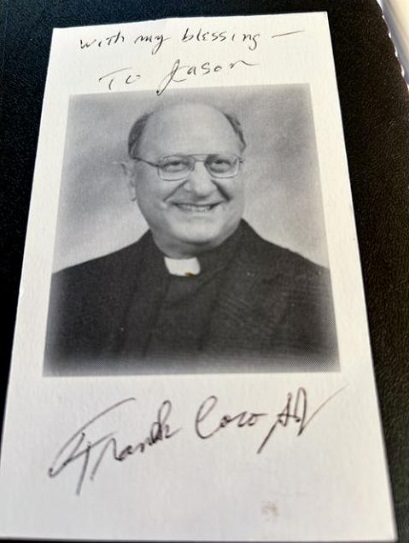

Of my teachers at Jesuit High School of New Orleans, Fr. Frank Coco was special. Balding, animated and jovial, Coco guided us through The Canterbury Tales, reading Old English aloud to show how language evolved.

Coco also played jazz clarinet. During carnival season, he invited us to seek him out with jazz legend Pete Fountain’s Half-Fast Walking Club. Come Mardi Gras morning, Coco — dressed as an Indian, bedecked with plastic beads, clarinet aloft — ambled along St. Charles Avenue with Fountain’s band.

A few of us approached; he put his hand in a sack, saying, “Who-hooo: something for you!” and palmed us doubloons. Then he rejoined the band, wending jubilantly through the crowds.

Jump cut: In the summer of 1985, I was getting slammed in the Daily Advertiser of Lafayette, hub city of Cajun country in Louisiana, for my reporting in the weekly Times of Acadiana on the diocese’s cover-up of pedophile priests. An Advertiser editorialist sneered at “vultures of yellow journalism.”

My first child, Simonette, was 7 months old and the center of celebratory visits at the home of my mother-in-law in nearby Abbeville. My Cajun extended family was supportive if a bit baffled at my reporting. The blowback had me depressed.

The Times was getting favorable mail, as the publishers, Steve and Cherry May, stood their ground to the daily paper’s attacks. As all of that intensified, I got a letter at the Times from the Jesuit retreat center in an outlying village, Grand Coteau. Coco complimented me on “unity, coherence and emphasis” — the traits for good prose stressed at Jesuit High.

The next day, I drove out to the center where he led retreats. We walked along a path shaded by ancient oaks. I let it all out, the betrayal I felt at the church, confiding that Lafayette Bishop Gerard Frey was an alcoholic, absent for long stretches from the chancery. Coco nodded. “He’s not a bad man; but he failed on this, clearly.”

We went inside to a parlor. He kept listening, then said: “Your articles are fair. These things must be known.”

He asked about my spiritual life. I remember fulminating on the violation of innocents, and the larger issue of human suffering vs. a loving god. Free will was itself a mystery, he said at one point. We solved no metaphysical problems but after several hours, a soothing calm settled over me. At the end, he blessed me. “Keep praying, son. You’re on the right road.”

Coco performed with a jazz quartet in Lafayette; I saw him several times after that. He shared fragments of a memoir he was writing (Blessed Be Jazz, published in 2009). I felt boosted as the reporting continued.

In early 1986, my last major report ran in The Times of Acadiana, pinpointing seven priests who were shuffled from town to town after abusing children. Just before publication, editor Richard Baudouin and I had dinner. Richard graduated from Jesuit a few years after me. Over wine, we stewed on how much we did not know. I suggested he write an editorial calling on Frey and the vicar general, Msgr. Alexandre Larroque, to resign. He nodded, and said, “I’ve never written an editorial like that.”

“Richard, no one has ever written an editorial like that.”

Steve May, the publisher, fully supported the editorial. “Who are they to think they’re above the law?” May fumed in his office. “This is outrageous!”

The editorial provoked a call to May from Edmund Reggie, a retired judge in nearby Crowley. Reggie demanded a retraction. May asked Reggie if the article had mistakes. No, said Reggie, but you can’t run an editorial calling on the bishop to step down. Well, said May, the issue is out. Can’t change the editorial.

“Boy, you just shit in your mess kit,” May said Reggie told him.

Reggie and a prominent monsignor fomented an advertisers’ boycott that cost the paper, then billing about $1 million a year, some $20,000, the cost of an ad salesperson’s base salary, before commissions. Cooler heads prevailed, the boycott stopped; the paper kept on. And I moved on, tracking cases in other states.

I had not heard from Jesuit Fr. Pat Koch in many years when his letter came, Aug. 1, 1991, on the stationery of Jesuit College Preparatory School of Dallas, to say he had a new assignment. I had just received a contract for Lead Us Not Into Temptation, my book on clergy abuse. It includes Koch and Coco among Jesuits thanked in the acknowledgments.

Koch wrote of a transfer to a Lake Dallas retreat house: “I felt God nudging me in that direction. I will of course miss the young people I have been accustomed to dealing with for most of my life. I have many, many happy memories from my years of teaching at Jesuit of Dallas, Spring Hill College, Corpus Christi Minor Seminary and Jesuit of New Orleans.” He concludes: “I cherish your continuing friendship and love.”

I see now that he left Jesuit Prep not by God’s nudging, but more likely forced out by Jesuit superiors. He had had a seven-year period as principal of the school, a brief one-year term as president, and several secondary positions from which abuse allegations subsequently arose, according to Mike Pedevilla, one of the former students who accuse Koch of sexual abuse.

After the settlement in Dallas with the school and the Jesuit province, survivors called Pedevilla, and he learned that Jesuit Prep had made at least four secret payments predicated on victims’ silence.

How does one assess a disparity so gigantic of Koch’s “happy memories” and his destructive impact on youths that exploded more than a generation later?

Before those revelations, Koch officiated at the wedding of a lawyer who sued the Lafayette Diocese on behalf of victims of Fr. Gilbert Gauthe.

Blessed be jazz

Across the years, I have written about the church crisis, intercut with other books and projects on New Orleans. I followed jazz, an art form spawned by Black cultural memory and polyrhythms, as a stream of hope. Sometimes I went for stretches unable to attend Mass. I go back for reasons I keep trying to explain.

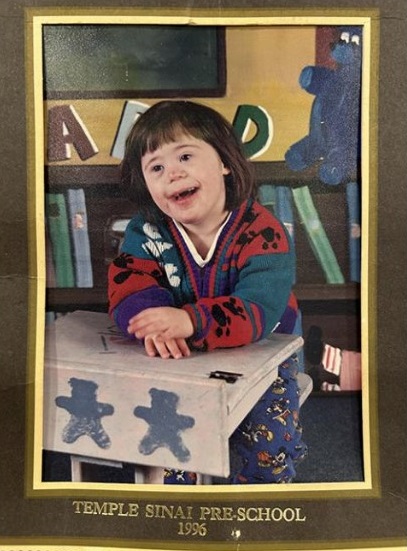

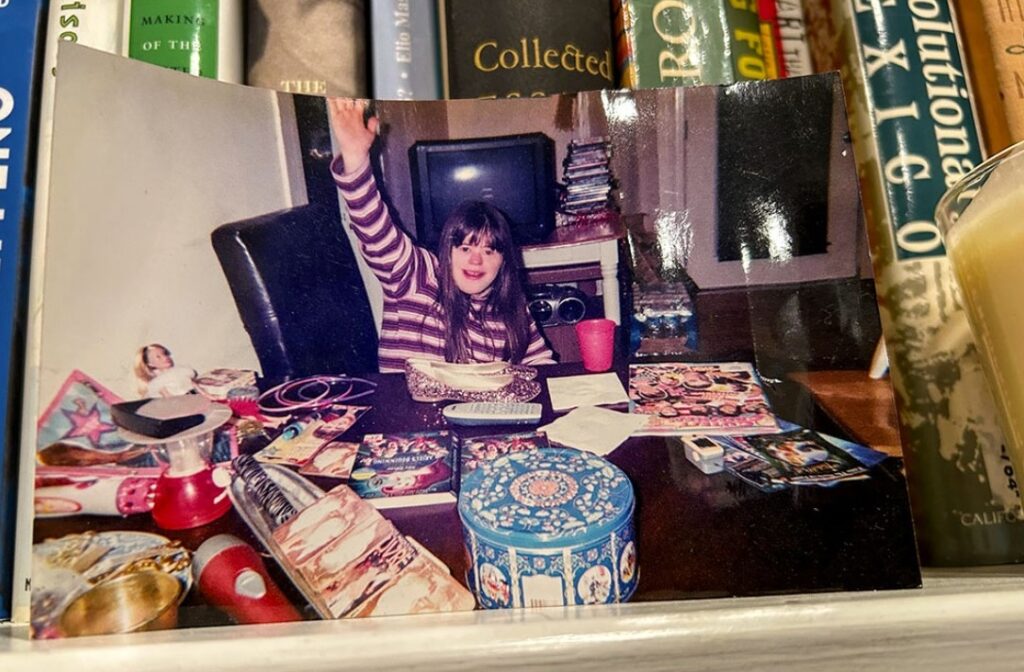

In 1991, my second child arrived. Ariel, a girl with Down syndrome. Soon thereafter, an anger attack hit me. I was furious — after so much struggle on the book, a disabled child! And then I centered myself as we faced the task of dealing with Ariel’s limitations.

Her slow-budding discovery of language in ritual word games we shared gave me hope despite the sadness of knowing she would never be robust. At 2, she survived open heart surgery. We soon learned her lungs were compromised. As Ariel showed resilience, pressures built on my wife and me. In 1996, we divorced, with a shared custody agreement.

Ariel settled in at St. Michael Special School, founded by nuns in the Irish Channel neighborhood of New Orleans; her religion lessons came home. I began a nightly prayer ritual as she lay in bed, call-and-response, saying, “Thank you, Jesus,” and she would run down the litany of her mom, Lisa; her sister, Simonette; Aunt Mimi; grandmothers in both homes; adding pets and Disney cartoon characters. The dawning of her tiny cosmos gave me hope beyond the darkness of my reporting. I kept praying for her to live.

In 2004, after the long waltz of a midlife courtship, I was about to marry again. I had no intention of getting an annulment, answering personal questions about a failed marriage to canon lawyers in a chancery I knew had sheltered pedophiles. My former wife wanted no annulment either. So I was ineligible for a church wedding.

My erudite mother, who had given me books by Thomas Merton, Walker Percy and Dorothy Day in high school, wondered if a priest might bless the union. One priest told me canon law forbade it. I called Coco, whom I hadn’t seen in several years, and gave him the facts. His Socratic approach was consoling.

“Well, I think we must ask, what is the greater good? Is it better for Jason and Melanie to marry before the state, without the church’s spiritual comfort? Or should the church play a role? I think we can say yes for the greater good.”

We married in the Audubon Golf Club before 80 people. After the judge pronounced us wedded, Coco stood. “The state has spoken. Jason and Melanie are married.” He then read the rite of Christian marriage; we said “I do” again — probably violating canon law — and he blessed us. Then he pulled out the clarinet and played “Love Is a Many Splendored Thing” to some misty eyes.

New Orleans in context

In 2018, Pope Francis made a dramatic shift on the abuse crisis after a trip to Chile, where people protested the cover-up of a powerful priest in Santiago. The pope soon met with survivors, ordered an investigation of the Chilean hierarchy and accepted resignations from one-third of the country’s bishops, including a prelate he had previously defended. “I was part of the problem,” the pope told the survivors he met with in Rome.

“Those of us journalists who were younger had a particularly hard time,” Colleen Dulle, a Vatican correspondent for America Media, the Jesuit news organization, writes in a new book, Struck Down, Not Destroyed.

“Now, we were having to confront the evil within the church as employees and representatives of the institution,” notes Dulle. “We all believed that for the church to move forward in any credible way, it first had to confront the whole truth.”

Meanwhile, nonreligious elite East Coast private schools like Choate, Deerfield, Phillips and Horace Mann had also paid negotiated settlements to abuse survivors.

Catholic religious orders have a different asset profile than dioceses. A bishop can close parishes, sell churches or liquidate other holdings to cover settlements. Religious order schools often have generous alumni support and property off-limits to a diocese. In New Orleans, a suburban street leading to Louis Armstrong International Airport is called Loyola Drive, much of the land once owned by the Jesuits. But few religious orders have assets to rival the diocese they serve.

Jesuit High School of New Orleans has a distinguished history of National Merit Finalists. Its notable alumni include Mitch Landrieu, the former mayor and infrastructure czar under President Joe Biden; Marc Morial, a former mayor and now head of the National Urban League; jazz singer and actor Harry Connick Jr.; retired baseball star Will Clark; and novelist John Gregory Brown. The $12,600 tuition is near the lowest of Jesuit schools nationwide. JHS’s full cost per student is $17,454, the balance covered by donations. The school has need-based scholarships.

Jesuit College Preparatory School in Dallas charges $26,300. Georgetown Prep in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., has a tuition of $46,065. Alumni donations are pivotal to most Jesuit schools.

Of the more than 40 church bankruptcies, the Jesuits’ Oregon Province took Chapter 11 in 2009 and resolved it in 2011 with a $166 million settlement to victims from the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, where the order sent missionary priests known to be serial sex offenders. The 500 claims “were primarily from Alaska natives and Native Americans who said they were abused as children by priests at the order’s schools in remote Alaskan villages and U.S. Indian reservations,” Catholic News Service reported.

Starting about 2015, Jesuit High settled several cases that centered on the late Pete Modica, a school custodian and former minor league baseball player. In the early 1960s, Modica had received a suspended sentence from a suburban court after admitting he had oral sex with two 13-year-olds. Somehow, he got hired at Jesuit in the 1970s and began grooming neighborhood kids he then abused.

Jesuit Fr. Cornelius Carr was accused but not convicted of participating in the abuse against one youth, Richard Windmann, who lived nearby. Windmann received a $450,000 settlement “after the Jesuit order had settled other 1970s-era abuse claims, implicating other employees at the Mid-City campus, such as Donald Dickerson — a teacher who was studying to be a priest — and a religious brother named Claude Ory,” Ramon Antonio Vargas, a 2005 Jesuit grad, reported in 2019.

Dickerson, now deceased, was frequently reassigned, as revealed in the documents from Dallas, where he had victims, too. The Jesuits face a lawsuit against Loyola University New Orleans over allegations that Dickerson years ago raped a freshman, age 17.

Jesuit High faces three lawsuits outside of the archdiocese’s long-dragging litigation. Settlement attempts collapsed, says attorney Richard Trahant, a 1985 graduate, after an attorney for the school turned the discussion over an agreement into a harsh cross-examination of his client.

The school has filed motions seeking to dismiss the cases, a strategy Trahant derides “as playing for time. To this point, they have lost at every appellate court and recently went back to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which upheld the constitutionality of the law they are challenging. It’s a real Hail Mary pass.”

In response to an interview request for this report, Fr. Thomas Greene, the Jesuit provincial (and a former attorney) who was central to the Dallas agreement, replied: “We [the province] do not comment on litigation, but I would refer you to the submissions made by our counsel in the cases you mention.”

On May 19, law firms representing the high school and the Jesuits’ Central and Southern Province filed a writ application to the Louisiana Supreme Court — which had previously upheld the legislature’s new law — asking it to review the law. The court can do so or turn the case back. The Jesuits’ attorneys argued that their clients’ property rights were constitutionally violated by allowing survivors extended time to file cases seeking compensation for abuse. The new law, they argue, is gravely flawed:

The legislature could have, for example, established a state fund to indemnify parties such as JHS and the UCS Province for losses suffered as a result of revived claims. The legislature also could have limited the damages recoverable through revived claims, as it has limited damages in other contexts … (imposing $500,000 limit for personal injury claims against the state and its political subdivisions … [or] imposing $500,000 limit for medical malpractice claims). Alternatively, the legislature could have revived only claims against the actual perpetrators of alleged abuse, or established a higher burden of proof for revived claims — as some other states have done.

If the legislature had done any of these things, or made any effort whatsoever to provide some offset or other compensation for the property that was being taken, this Court could then consider whether the compensation provided is constitutionally adequate. Instead, the legislature apparently never even considered any method for providing fair and reasonable compensation for defendants who would face costly lawsuits and potentially ruinous liability due to the revival of previously expired claims. This failure renders [the revised laws] unconstitutional on their face and, therefore, unenforceable in this lawsuit or in any other case.

The high court denied the writ, sending the Jesuits back into litigation with the survivors.

Meanwhile, a sign of shifting attitudes in Catholic South Louisiana came in June when attorney Kristi Schubert tried a case on behalf of a 68-year-old man, abused decades ago by a now-deceased Holy Cross brother. The jury verdict of $2.4 million was a flare to institutions like Jesuit, and at least three other high schools that also face such claims, according to Trahant.

Soren Gisleson, an abuse survivors’ litigator, graduated from Jesuit in 1988, three years after his colleague Trahant, and in 1999 from Loyola law school. The Jesuit cases have made Gisleson revisit the geography of his youth.

A prominent Uptown lawyer’s son, he rode his bicycle as a boy on the Loyola campus and leafy Audubon Park nearby. Years later, as the abuse lawsuits made news, Gisleson got emails from out-of-touch high school friends that, he says, he never opened.

“These cases track other abuse survivors’ claims, but they tend to demystify my upbringing, the idea that New Orleans was this magical place where great things happen and we were the best and brightest at Jesuit; your experience will elevate you as leaders of men. The older I get, I realize how complicated it is looking back. The past is different things to different people. Some rely on the past to pat themselves on the back: Hey, see how well I’ve done! Others seek a truer grasp on reality. When you confront the experiences that people unlike you had — not the past you remember — it’s like sand shifting under your feet.”

That reality of a changing past, breaking the terrain of common memory, is the Roman Catholic Church’s epic task as the aching crisis wears on.

A national perspective

“What monetary figure applies when a figure of God has raped someone? It’s a spiritual wound difficult to comprehend, much less heal,” Jesuit Fr. Gerard McGlone, a psychotherapist with long experience treating victims and religious perpetrators, told me. A clergy abuse survivor himself, McGlone is a research fellow at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs.

“The huge challenge we face, as a religious order and the larger church, is how do we put reparation figures in the light of restorative justice? I have often thought of a parent who loses a child, the pain that never goes away. It’s our sacramental being as a church, our duty as Christians to acknowledge sins of the past, to see them as crimes of history, and give traumatized people a road to healing. The settlement in Dallas met the survivor and tended to the wounds.”

On Dec. 10, 2018, the Jesuits’ Central and Southern Province released a list of credibly accused priests, including the late Fr. Donald Pearce. In my high school years, Pearce was the prefect of discipline and later president. An imposing figure who smoked cigarettes in his office, he once complimented me on an article for the school paper. I avoided him so as not to land in penance hall. Many years later, a man who was ahead of me in school said Pearce had paddled him so hard for some infraction he thought he was “getting erotic kicks” out of it.

With capsule summaries of Koch, Pearce, Dickerson and others, the updated Jesuit website evinces tortured logic:

A finding of credibility of an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor or vulnerable adult is based on a belief, with moral certitude, after careful investigation and review by professionals, that an incident of sexual abuse of a minor or vulnerable adult occurred, or probably occurred, with the possibility that it did not occur being highly unlikely. “Moral certitude” in this context means a high degree of probability, but short of absolute certainty. As such, inclusion on this list does not imply the allegations are true and correct or that the accused individual has been found guilty of a crime or liable for civil claims.

Pearce’s capsule bio says, “Estimated Timeframe of Abuse: 1960s.” He retired in 2003 “due to poor health” and died in 2016. The capsule on Koch is terse: “deceased when allegation established.”

In March 2022 in Dallas at the final negotiation with the lawyers, survivors and Jesuit provincial Greene, Pedevilla said he had heard from 140 men claiming abuse at the school, though many of them would never file suit for fear of personal or professional repercussions if their identities were known. Pedevilla asked that the Jesuits establish a reparations fund and a path for survivors to find reconciliation outside the legal process. Greene said nothing, but his attorneys vetoed it.

In response to the crisis, the Jesuits’ Fordham University in New York began a sweeping study of how Jesuit institutions should respond to clergy abuse within the ranks, inspired in part by an investigation that Georgetown University began of the long-term impact from its early Jesuit slaveholders, who sold 272 African-blooded people to Louisiana plantations. The Georgetown Memory Project is a template for universities facing these issues.

Historic sex abuse is more challenging. Fordham’s Taking Responsibility initiative has recommendations by various scholars, some of which spotlight specific cases as symptomatic of the larger crisis. From Page 33:

One of the most publicized cases of clerical sexual abuse in the U.S. concerned the late former Jesuit priest Donald McGuire. McGuire not only received his Ph.D. from Loyola [of Chicago] in 1976, he also taught at Loyola Academy and developed mission and retreat programs in Chicago and numerous other locations. His official posting and address, however, was always Chicago. He officially lived here during the years 2002-2005, when criminal charges were brought against him, and well-publicized lawsuits followed. McGuire was arrested in 2005, and subsequently sentenced to seven years of prison time in 2006. His sentence was increased to twenty-five years in 2009 after he was additionally convicted of a federal crime. McGuire died in federal prison in 2017. But as recently as 2019, a new victim has come forward.

Profiling a sexual criminal associated with a university, or school, right there for anyone to read, is part of the painful road toward restorative justice, doing right by victims of the past. Failure to confront that hidden past invites it to betray us again.

And yet, defenders of my high school might argue, why the hell should we give some public declaration or website space to priests or laymen who betrayed the Ignatian ideals by plundering young lives, tearing up fragile families? Particularly dead priests who stand now like narcissistic ghosts hungry for attention at being profiled? If we have to make settlements, pay, apologize, move on.

A part of me, proud of my Jesuit education, gets that. Why invite more bad publicity? The Dallas resolution suggests another path but there is no guarantee it will be used again in Dallas, where Pedevilla keeps hearing from victims.

The survivors in their quest for justice, and a measure of healing, function like the chorus of a Greek tragedy, warning us that a moral order has been broken. In Greek drama, the chorus is on the side of the gods, however jaded or meddlesome they may be. In our day, the survivors occupy a zone between God and the church.

How do we repair a structure that long seemed good, as we witness its evil underside? Gisleson’s notion of a changing past invites a reckoning. Jesuit High encouraged its students to be “men for others.” How should men for others respond to wounded brethren, hidden in shame?

Over many years of reporting on this crisis, I have met dozens of survivors and read the testimonies of countless others. Along the way I became friends with Fr. Bruce Teague, a Massachusetts priest who allied himself with survivors after the 2002 Boston Globe Spotlight series. Teague announced that he, too, was a youth abused by a priest.

Teague and I share an appreciation of Flannery O’Connor’s Christ-haunted characters. Teague visited the grave of the priest who abused him as a boy. “I’m in the process of trying to forgive him,” he told a reporter in 2003.

I make regular visits to a cemetery near my home where Ariel is buried. She died in late 2008, just past 17, after a long struggle with heart failure. The beauty of her radical innocence is a light ever bright for me.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, she spent stretches with me while her mother was dealing with adjustors over her flooded house. My house did not take water. At Ariel’s insistence, trying to understand “her-cane,” we went driving in the broken mud-town. As we drove along streets with the waterline etched on empty houses, I played gospel music for uplift, telling her how the houses would slowly get rebuilt.

Before the flood, at a corner of Claiborne Avenue near her mom’s house, a homeless Black man had stood begging. Each time we approached, Ariel tugged my elbow, and I stopped, giving the man money. She waved to him, he waved back. After the flood, he was no longer there.

“Man gone,” she said. I tried explaining how people left to find safer places, slowly repeating the information as she repeated, “Man gone.” This went on for a while.

Months later, as I left a convenience store on Claiborne, a raggedy voice said: “How’s that lul girl?” There he was. I handed him a fiver. “She’s OK; she asks about you.” He nodded. “Tell her I came through.” I shared this small tale of elation with Ariel as the city limped along.

Sometime later, as the recovery took hold, I went to Mass with Ariel and my mother, Mary Frances, at Mater Dolorosa on Carrollton Avenue. Ariel loved the liturgy, without grasping the sermons; she swayed to songs she could not sing and relished the exchange of peace, shaking hands and waving to people. One Sunday, retired District Attorney Harry Connick Sr., who has since died, entered the pew to Ariel’s left, unaware that I sat a few feet away.

Connick detested me for what I had written about his botched prosecution of a notorious predator priest, Dino Cinel, whose cache of pornography — including videos of his young victims, discovered by another priest — was transferred by church attorneys to the DA’s office. There it sat, until a staff investigator leaked dubs to a TV reporter, who surprised Connick on camera, asking if he had stalled “because it was Holy Mother the church?”

Connick blurted: “That was an absolute consideration.” Cinel was eventually tried and acquitted; the church paid civil settlements. Sometime later, on a satellite interview with Connick and Geraldo Rivera, I ripped into Connick.

When the handshake of peace began, my little girl turned to the aging pol and said, “My name Ariel Berry.” He smiled, and she took his hand and pulled it over, saying, “This my dad, Jason Berry.” Connick blushed, taking my hand.

In driving around the city, thinking of my child as a person for others, I give money to people begging on street corners. Some of them sleep on benches at a park near my grocery store. On visits to Ariel’s grave, I pray for a visitation of her spirit; that happens occasionally in dreams whose messages are not altogether clear. I wonder what the radical innocence she radiated means in a world so broken and corrupted as ours.

Two or three times a month I go to Mass, seeking a connection to my daughter’s spirit, searching for liturgies that occasionally lift me, more often not. I say prayers of thanks for the family that shaped me, the relatives and friends among the beloved dead, and the priests like Frank Coco who taught me. I suspect it is a prompting of Ariel that has me, at times, praying for the soul of Patrick Koch.

Editor’s note: This is the final installment of a four-part series looking at the long-term consequences of the priest abuse scandal and the legal entanglements that have followed, especially in the New Orleans Archdiocese. Previous installments: