DALLAS (TX)

National Catholic Reporter [Kansas City MO]

December 11, 2025

By Jason Berry

In 1965, just shy of my junior year at Jesuit High School of New Orleans, with good potential as an offensive end, I had an epiphany in the muddy slog of August football practice. Why are you doing something you don’t like? Soon, I quit. And was trailed by guilt for a dereliction of duty. Jesuit vaunted student achievements of all kinds. I played on the golf team and did some pieces for the school paper. Jesuit fostered a fraternal culture, molding friendships I carry to this day.

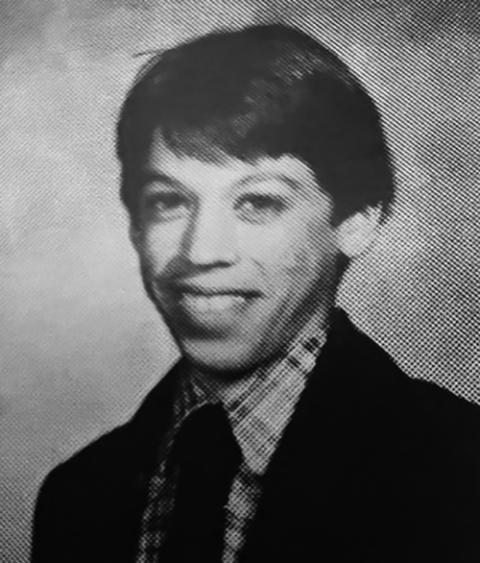

For a writer, the Jesuits’ stress on Socratic thinking was a gift. Question seeks answer, answer sparks new questions, yielding synthesis as the wheel of learning turns. Picture Kevin Trower, the cerebral basketball coach, a layman teaching Latin, pacing the floor with furrowed brow, book in hand on Caesar’s Gallic Wars. “Alea iacta est. The die is cast! What does this tell us? Think, boys! Think!”

The priests encouraged us to be “men for others,” responsibility to those on the margins, emulating Jesus. Francis, the first Jesuit pope, emphasized embracing dignity of the dispossessed, clashing with a creed of wealth as virtue. I had no idea how “men for others” would color my spiritual odyssey, nor how that ethos bears on the surfacing world of abuse survivors.

In 1966, on certain nights, I sat in a school parlor with my religion teacher, troubled by a loving father who, after work, downed a few stiff ones, watched Vietnam War protests on TV, then drifted off to bed. Ashamed to tell Fr. Pat Koch how Dad was there-but-not-there. I brooded over quitting football.

“Think of yourself in five years, Jason. What difference will football make?”

Koch (pronounced Coke) entreated me to pray for a closeness with Jesus. He blessed me when we finished. I left feeling clean, a burden lifted. A few years later, Dad got sober, bounced back as a benevolent paterfamilias. By then, Koch had gone to Jesuit College Preparatory School of Dallas.

Today, I wince on reading about Koch in a 2021 deposition of Fr. Philip Postell, the Dallas Jesuit Prep president from 1992 to 2011. Nine men alleged they were sexually abused as teenagers, with the cases involving five priests in the ’70s and ’80s. Four men accused Koch, who died in 2006 at 78. His Legacy obituary is full of praise from people with memories like mine.

Postell, 20 years younger than Koch, testified they were not close. I recall Postell, who taught at my high school: a scholastic, not yet ordained, easygoing with a wry sense of humor. Postell in testimony was 83, questioned by Brent Walker, an adroit attorney among several lawyers suing the Dallas Diocese, Jesuit Prep and the Jesuits’ Central and Southern Province, among others.

Walker reads from a 1965 letter by an official at the Corpus Christi Minor Seminary: Teenage students complained of Koch, recently ordained, coming on to them. “If you had heard,” Walker asks Postell, who had no role in that conflict, “that a priest got a boy drunk, took off his clothes and got in bed with him and kissing him, that would have been an automatic dismissal, correct?”

An ordination Mass in the chapel of the Corpus Christi Minor Seminary in Texas in 1961 (CNS/John Haring)

Postell: “It would have been a red flag. I would have talked to the offending priest immediately, reported that to the provincial for further action.”

“The problem with Father Koch is an old one,” a seminary priest wrote the Jesuit provincial in 1965. “Every year I have had to speak with Father Koch about demonstrations of affection. … His response was that he resented people spying on him.”

The seminary rector worried about “a very bad source of public relations” if boys quit and told people about Koch.

Why, Walker asks, wasn’t Koch expelled from the order?

Postell said that on such a report today, “we would act pell-mell to dismiss … the priest or at least get him out of that particular venue. In those days we were a little more cautious in moving a guy for many reasons. Abusing a kid sexually was very rare. We didn’t have a vocabulary for it. But knowing what I know now, no one would get that far in the pipeline.”

On Jan. 12, 1966, Koch arrived at Jesuit High New Orleans, with all that tortured correspondence to surface half a century later. I sat across from the young priest exiled from Texas for abusing seminarians my age. How vulnerable I was! He never made a move on me.

Reading about Koch’s abuses threw me into a strange zone between appreciating his influence on me and revulsion at what he did to those other men.

For senior retreat, Koch asked me to share a room with one of seven Negroes (the word used then) in our class of 160. Jesuit was among New Orleans’ first white schools to integrate; still, one heard sotto voce racism by some classmates and the N-word at the homes of a few friends. My parents weren’t activists, but they supported integration and forbade any language like that in our house.

Donald Soniat was the son of the local NAACP leader. As we sat on separate beds, he recounted his father’s Civil Rights activism (events I’d followed like foreign news) — his dad arrested for sitting in the wrong part of a city hall cafeteria. My dad was vice president of an unrelated cafeteria chain. Donald opened my eyes to Black struggle.

A few years later, as a Georgetown undergraduate, I followed The Washington Post coverage of the South’s racial conflicts, embarrassed about where I was from. A week after graduation in 1971, I went to Mississippi and joined Charles Evers’ longshot run for governor. Seeing events through a prism of Black people changed me. But not for Koch and Soniat, where would life have taken me? In 1973, I published a book on the campaign and became a freelance writer.

Declamations in Dallas

The 2018 Pennsylvania Grand Jury report investigating the church found 1,000 victims of priests and long-secret documents exposing bishops’ deceitful strategies protecting predators. The report spurred some 26 state attorneys general to conduct investigations; Texas was among them. Dioceses began releasing perpetrator lists.

On January 31, 2019, the Dallas Diocese issued a list naming Koch, who had not been on the Dallas Jesuits’ list.

The news hit Mike Pedevilla like an electrical charge. An executive with a national health care services company, Pedevilla was a 1983 Jesuit Prep graduate from a prominent North Dallas family. He told me about his freshman year, when Koch began abusing him, and how it continued. With too much pot smoking and getting into fights, he still made it to graduation “because my mother kept meeting with the young Assistant Principal Mike Earsing, who saw some good in me.”

Pedevilla told no one for decades. Now there was TV coverage of Koch’s name on the list in Dallas, and a list by the Diocese of Corpus Christi, Texas.

Pedevilla met with high-profile plaintiff lawyers Charla Aldous and Walker. They knew a lawsuit against Jesuit Prep would be explosive. File as a John Doe, advised Walker. Pedevilla agreed, but from the lawsuit’s description of him, five friends quickly called, in sympathy, but warning that he was in for the fight of his life. He told Walker to make his name public.

After all the years of bottled trauma, Pedevilla sat in a preliminary meeting with his lawyers and the school attorneys. The school president, Earsing, whom he recalled from many years before, approached him. Pedevilla said: “I don’t want to hurt Jesuit Prep.”

Earsing, he says, replied: “I’m the one who’s sorry. Thank you for doing this,” as the two men embraced, fighting back tears.

Separate from that, David Finn, a former judge, spoke for Koch’s family and friends, aghast and threatening a protest at the Vatican. “Father Koch is revered by many Dallas Jesuit students, myself included,” Finn stated. “His picture used to hang up, until this allegation came out a week ago, at Dallas Jesuit and at St. Rita’s Church where he was a priest for years. … The family’s position is that, by erring on the side of caution you might have some collateral damage here. Maybe the bishop made — and I’m not saying it was intentional — but maybe he made a mistake in including Father Koch on the list.”

After meeting with Koch’s family and Finn, Bishop Edward Burns stated that the process to compile a list of priests “credibly accused” of child sex abuse “began with an outside group of former state and federal law enforcement officers who went through all of our priest files and identified those which contained allegations of the sexual abuse of minors.” The Diocesan Review Board with professional lay experts made final recommendations for disclosure.

Brendan Higgins, a former reporter-anchorman at KTVT, the CBS station in Dallas-Fort Worth, filed suit against Jesuit Prep and the Jesuit province, alleging abuse by Koch. Higgins filed suit under a pseudonym but soon went public, too. Two other plaintiffs sued with pseudonyms, saying Koch had abused them.

“We never wanted to sue the school,” Higgins told NCR. “We were not angry with Jesuit Prep because of what one pervert did to us. But we didn’t want the Vatican to clear him.” The Vatican appeal fizzled; two more men filed cases as Koch victims.

As news of the lawsuits spread, Pedevilla attended a funeral where one of the school’s biggest benefactors pulled him aside. “Mike, my wife and I are behind you 100%.” The donor told him to call Lee Taft, a lawyer who had left a high-dollar Texas practice to earn a Master of Divinity at Harvard, and now, back in Dallas, specialized in conflict resolutions.

“We wanted to spare the school as much of the loss as possible,” Pedevilla told me, “and force accountability directly on the Jesuits. Lee Taft was absolutely pivotal; he was the architect of this reconciliation model.”

Taft declined an interview request for this article.

As negotiating sessions quickened after the COVID-19 shutdown, Pedevilla sensed a breakthrough with the arrival of a new Jesuit provincial, Fr. Thomas Greene, a product of Jesuit New Orleans, and an attorney before entering the Society of Jesus. Greene, says Pedevilla, was “apologetic, open-armed, ashamed of what he said his fellow Jesuits did.”

Greene asked if the survivors would agree to interviews with a Houston investigator for the Jesuits. They agreed.

Higgins also came from North Dallas’ affluent Catholic society; he was adopted. His father was a corporate lawyer, his mother a local Right to Life leader. “On paper, it looked like I won the lottery. But my dad was a violent binge drinker, the victim of an Irish Catholic upbringing in the northeast, that cycle where his dad beat him and he beat the shit out of my brother and me, maybe not as bad. My mom took me to protests at abortion clinics. I had a detached upbringing.”

His parents insisted he enroll freshman year, 1983, at prestigious Jesuit Prep. “My friends were going to other schools. I was sullen, walking around with my shoulders slumped, sad-looking I’m sure. Koch had been to my house when I was growing up. He was my freshman theology teacher. He told me, ‘I know your dad’s kind of brutal.’ He kept talking to me; in retrospect I think he saw me as a target.”

Things brightened his sophomore year. Higgins was a standout on the tennis team, “one of the best in the country at the time, and I had a girlfriend.”

In the fall of 1984, Koch told Higgins’ mom he was headed to New Orleans to say a funeral. Would Brendan like to go and visit the Louisiana World Exposition? Higgins resisted; she urged him to see the world’s fair.

“We were staying in a dormitory with some empty rooms at Loyola. Koch told the sister when we arrived that we’d stay in the same room. She was stone-cold: Oh, no, he’ll have his own room. I had a creepy feeling. At bedtime, he wanted me to sit on the bed as he lay down, wanting to talk. I said no. I went to bed. I woke up with him standing over me, stroking my head and his other hand stroking his penis. I ran out of the room to a bathroom in the guest suite area and sat against the door, looking at a mirror, thinking, You’re by yourself. Nobody’s going to help. I sat there for hours.”

The next day, he deflected more advances by Koch, says Higgins. “It was pretty horrific.”

Back home, he told no one. As spring semester ebbed, he defiantly told his parents he would not go back to Jesuit Prep. Junior year he transferred to Hillcrest, a public high school. He went on to University of North Texas, graduating with a degree in broadcast journalism. By the time he was 30, he was an NBC reporter in New York.

After his father died, he moved back to Dallas to help his mother, landing at the CBS affiliate. Today, with two sons who have graduated from college, he is an independent producer. Despite his contempt for Koch, Higgins says he donated to Jesuit Prep in later years, regretting he’d had to leave.

Postell’s pretrial testimony was a turning point. At the end of the long deposition, Postell said of the reassignment history of Koch and four other priests: “I’m embarrassed, I am ashamed. I apologize for the harm it has done, for what the school has done to these young men. I see some of the long-range damage done.”

On March 31, 2022, The Dallas Morning News reported that a settlement reached by the parties “calls for reforms in how the school, the Diocese and the religious order handle abuse reports. Details about the financial compensation for victims remain undisclosed.”

Two additional Koch survivors, represented by other attorneys, participated in the negotiated settlement — totaling six men accusing Koch of abuse at Jesuit Prep.

Postell’s name was removed from the school’s stadium, which Pedevilla insisted be part of the agreement.

Higgins, without disclosing specifics, said the Jesuit order paid most of the claims. “Nobody in our group wanted to hurt the school. The school went toe to toe with the province.”

Earsing, the school president, said in a statement:

Rather than turning away from our past, we will memorialize it by creating a special space in our chapel where our community may pray for all people who have been abused by priests or anyone in religious authority. We live in a time where we are confronting anew painful facts about our country, our fellow citizens, and our Church…. In coming forward, these men have exemplified our school’s motto of being “men for others.” For that, I am forever grateful. Because yesterday we were apart, and today we are reunited.

Greene, the provincial, officiated at a Mass of Hope and Healing for clergy abuse survivors and families, held at Jesuit Prep.

On May 19, 2022, Higgins and another Koch survivor who had left for another school received honorary Jesuit Prep degrees. The night before, Higgins dreamed he was stuck in a meeting with his parents and Koch, coaxing him to stay at the school. As Earsing placed a medal of St. Ignatius, founder of the Jesuit order, around his neck, Higgins choked up.

“Some really great people there went out of the way to do the right thing,” Higgins told me. “The Catholic experience was a big problem for me, but culturally, I’m a longtime St. Vincent De Paul volunteer. I go to church but it depends — sometimes an Episcopal church, sometimes a Catholic. Dogmatically I’ve never bought into the full Christian teaching, but I do like the ethical barometer.”

by Jason Berry

Read this next: New Orleans Archdiocese bankruptcy pulls abuse survivor into prolonged ordeal

Editor’s note: This is Part 3 of a four-part series looking at the long-term consequences of the priest abuse scandal and the legal entanglements that have followed, especially in the New Orleans Archdiocese. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here. The Fund for Investigative Journalism supported this series.This story appears in the The Reckoning feature series. View the full series.