BOSTON (MA)

National Catholic Reporter [Kansas City MO]

January 2, 2026

By James M. O'Toole and Ryan Di Corporo

[Photo above: Historian James O’Toole is the author of the book For I Have Sinned: The Rise and Fall of Catholic Confession in America. (Courtesy of James O’Toole)]

In October 2025, Washington state agreed to withdraw a controversial mandate compelling priests to report allegations of sexual abuse specifically revealed during the sacrament of confession. The bill, supported by Catholic advocates for clergy abuse survivors but contested by the state’s three Catholic dioceses and the Justice Department, faced intense opposition from church officials as representing a blatant violation of religious freedom and another example of government encroachment on church affairs.

Under canon law, the seal of confession is absolute and inviolable; Seattle Archbishop Paul Etienne warned priests in May that they would face excommunication for breaking it. But Catholic supporters of the Washington statute say the church has a legal and ethical duty to report sex abuse, even abuse discussed during the sacrament, to the proper authorities — and that keeping secret these potential crimes only protects predators.

Of course, the state’s attempts to root out sexual abuse by focusing, in part, on the privacy of confession assumes that American Catholics are still celebrating the sacrament. But only a minority of the faithful are seeking out confession at all, finds author James O’Toole in his urgent, provocative new study of the sacrament, For I Have Sinned: The Rise and Fall of Catholic Confession in America.

O’Toole, professor of history emeritus and the university historian at Boston College, details the growth and eventual decline of confession in the United States, prompting questions about the sacrament’s future. A former archivist for the Boston Archdiocese, O’Toole spoke with the National Catholic Reporter about the once-widespread popularity of the sacrament in U.S. parishes, the ongoing controversy surrounding clergy-penitent confidentiality, and the social changes that he says dramatically reduced Americans’ visits to the confessional.

This interview has been edited for style, clarity and length.

NCR: In your book, you note that during the early 20th century “regular confession had taken hold as a defining characteristic of American Catholic religious life.” How did the sacrament gain prominence in the United States, specifically? How frequent was confession among Americans in previous centuries?

O’Toole: I see it in terms of the growth of Catholic infrastructure — ready access to church and priests and sacramental activity. In the early years of Catholicism in this country, during the colonial period and up until the time of the Civil War, that infrastructure really just wasn’t there, or it was spotty. As the infrastructure was put in place, priests could increasingly exhort their parishioners to develop regular [religious] habits. And laypeople said, “Okay, we’ll do that. That’s what being a Catholic is.”

As that infrastructure spread, it then became possible for priests to preach regular confession, and parishioners heard that message. I think as priests were increasingly telling their people that going to confession was a regular part of being Catholic, it helped increase the demand.

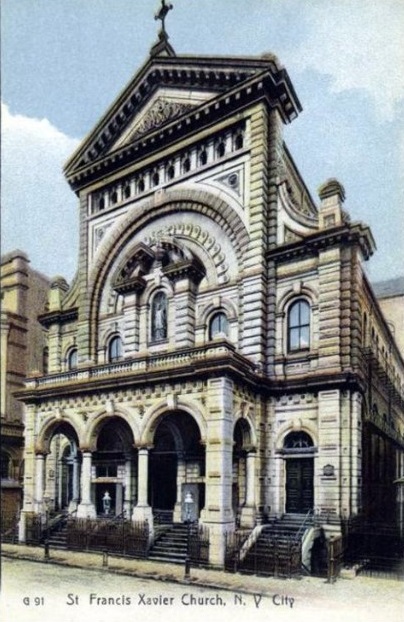

Your book contains some eye-popping statistics regarding the popularity of the sacrament in the late 19th century. For example, between July 1896 and June 1897, the Jesuit-run Church of St. Francis Xavier in New York City reported more than 173,000 confessions, about 475 a day. How was this possible? Did priests of that era spend most of their time hearing confessions?

They spent an awful lot of their time hearing confessions. Those numbers could be inflated by having schools in the parishes, where kids are brought to confession on a regular basis.

I think hearing confessions was a central part of what priests did all day long. I write in the book: “Parishioners and pastors encountered one another, however anonymously, most often in the confessional.” That was the point of contact, more so than Sunday Mass. At Mass, the priest was up on the altar talking in a foreign language, but in terms of personal encounter, it was in the confessional.

You write that the church developed a complex and specific system for categorizing the gravity of different sins and that the threat of perdition lurked around every corner. Did Catholics mainly understand their faith through avoiding sin? How did this thinking influence Americans’ relationship to confession?

That’s an interesting way to phrase it. Interesting to me is this notion of occasions of sin, not actual offenses themselves but circumstances in normal, everyday life that might lead me to sin. Once that idea has taken hold, you’re going to be thinking of sin all the time. Or you’re going to be urged to think about it all the time.

In the end, I suppose, that’s why people were going to confession so regularly. They had a way of looking at their own personal behavior and judging it in moral and ethical terms. The elaborate classifications of sins provided laypeople, I think, with words they could use in confession to confront that aspect of human behavior.

A priest’s decision to withhold absolution from a penitent under some circumstances remains controversial. It surprised me to read that absolution would be, occasionally, withheld from female penitents because they continued to use contraception, which church teaching prohibits. Was this the main reason for not granting forgiveness? What effect did this have on women seeking the sacrament?

The concern on the part of priests hearing confession, with regard to contraception, was not just with what they saw as sinful practices themselves. It was a question of recidivism. The presumption was that a person using contraception, if they confessed it, would probably continue to use it for at least some time. That was interpreted by priests as, “Well, they’re not really sorry. They know it’s wrong, but they’re going to continue to do it.” That was the basis for the denial of absolution. And I think that’s why, increasingly, men and women both simply stopped confessing it.

You write that the inviolable secrecy of the sacrament helped make confessing less “odious” to American Catholics. But “the investigation and exposure of clergy sexual abuse has prompted reconsideration of the absolute nature of the seal.” How can the church balance the confidentiality of the sacrament with its duty to protect the faithful, especially children, from harm? Do you think the church would ever allow exceptions to the seal?

This is a really tough one. This is one of those things where I say, isn’t there a way for society to do two things at once? We can obviously protect children and others from abuse, but we can do it without undermining … the free exercise of religion on the part of the church. How you do that is what’s being worked out. The church itself needs to maintain the scrutiny and disciplining of priests who err in this way. My own views are really very conflicted on this.

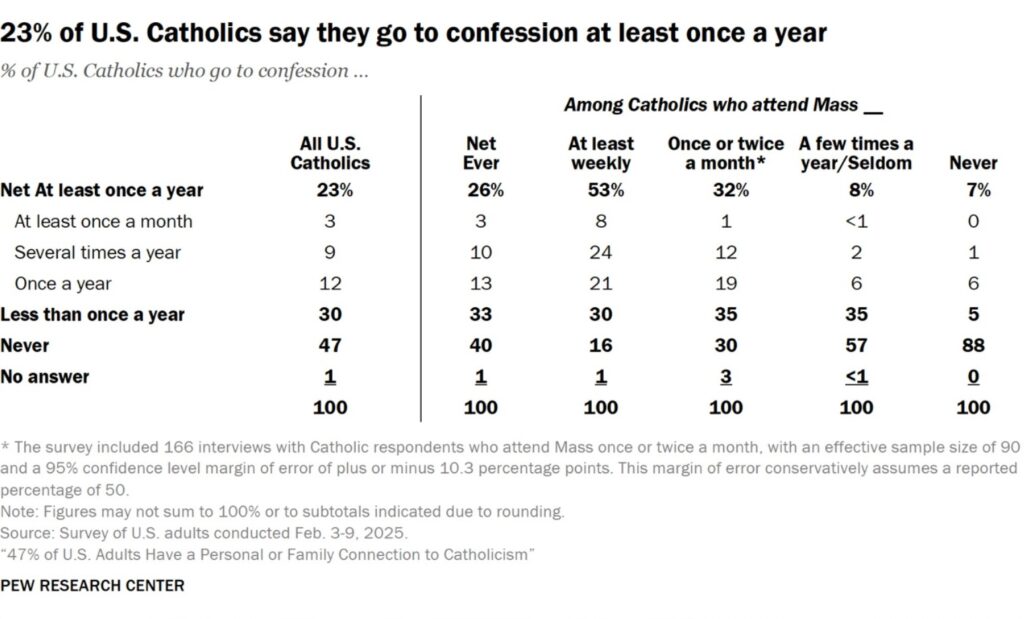

Your book discusses a sharp decline in the frequency of confession among American Catholics over several decades. You cite a 1975 survey that found the number of Catholics who sought out the sacrament decreased 21 percentage points, from 38 to 17%, in a single decade. Recent data reveals that only 23% of U.S. Catholics attend confession at least once per year. Do you expect numbers to decline even further?

Well, I don’t expect them to go up appreciably. At Boston College, where I am, students go to confession with their friends. Interview those same students 10 years after they graduate. Will they still be going to confession? I think we know the answer to that. They won’t.

About a month after my book came out, Christian Smith, a sociologist at Notre Dame, published a book called Why Religion Went Obsolete. He has studied baby boomers and post-boomer generations. His argument is basically that there was a social and cultural “perfect storm” around the turn of the present century. And when you combine that with scandals within the church, people in the post-boomer generations are just living in an entirely different mental world in which religious identity and practice becomes kind of obsolete. It just doesn’t say anything to them. I think that is what’s going on in regards to confession.

You offer several causes of death for the sacrament. But can you pinpoint a primary cause for confession’s current unpopularity among Catholics?

I’m reluctant to do that. One of the things that we academics do is try to complicate things rather than simplify them. I think it was the fact that all of those things were happening at the same time. As the church insisted on the sinfulness of contraception, I think that was the decisive case for any number of women.

More generally, I’d say the spread and acceptance of modern psychological concepts. As I wrote the book, I came to the conclusion that it was a really important part of the story. It implanted in people’s minds the idea that human behavior is a complex thing, and it’s more complex than the older system allowed for.

At the end of your book, you ask: “With confession gone, practiced today by only a tiny minority of Catholics, what, if anything, will take its place?” Do you foresee the sacrament evolving into something radically different — or is it really dead?

The sacrament, in its present form, probably is dead. People just aren’t doing it. It seems to me the church’s response to that circumstance is often: “We’ll just tell people again that they should be going to confession. They don’t understand how important it is. They don’t understand what it can do for them.” All that may be true, but just telling people to go back to confession hasn’t worked for the last 60 years, and I don’t see anything that’s going to change it.

That’s why I think new forms need to evolve, just as the practice of private confession itself evolved from the older forms of public penance and exclusion from the community. It seems to me the church is at the kind of hinge point it was at in the seventh century.

What that new form is going to be I don’t know. Historians do the past, not the future. Of course, it’ll take a couple of hundred years for that to happen. We’re not going to be around to see it.