BAYEUX (FRANCE)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

June 7, 2025

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

The crisis at Bétharram exposes the fault lines of France’s response to clergy sexual abuse, leading to further politicization of the issue.

The Church’s weak response leaves the survivors of abuse at Bétharram at the mercy of French politics, revictimizing them on a daily basis.

Despite French secularism and prior efforts from the Catholic Bishops to acknowledge the depth of crisis in their country, François Bayrou’s response to the crisis at Bétharram is verbose and inefficient.

Whoever follows French news these days would notice how many stories are associated, one way or the other, to issues of sexual abuse and violence. Last year, France, Europe and the world were in shock after knowing the details of Giséle Pelicot’s quest for justice.

More recently, France experienced a similar collective shock when a trial revealed details of how Joël Le Scouarnec, a surgeon, abused at least 300 of his patients. If that was not enough, France has had to contend with the effects of putting on trial a master thespian: Gérard Depardieu.

A fixture of global entertainment since the 1960s, Depardieu seized every chance at hand to turn the court into a stage. Yet, despite his theatrics, as the trial was not held at Cannes, the legal proceedings concluded with his sentencing to 18 months in prison.

Regarding the clergy sexual abuse crisis, it could be said that France’s current cycle of reckoning started by the end of the pandemic, back on November 6, 2021, when the French Conference of Bishops acknowledged their mistakes at the Atrium of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes (see the main picture for this story).

They did so, by calling their Church to “begin a journey of justice and forgiveness,” as the general secretary of the conference, Father Hugues de Woillemont, said that day. The day before, the Episcopate at large issued a statement, available in French only here, that would be similar to many other statements from other bishops worldwide.

It was not for the release of the Sauvé Report (available here in the official English-language translation), where the French bishops acknowledge specifically concrete, systematic mistakes of the Catholic Church in the French-speaking world and more specifically in France.

Despite the calls for forgiveness, Jean-Marie Delbos, a survivor of abuse at Bétharram, did what many victims all over the world have to do to force the Catholic bishops and public opinion at large to pay attention to their plight: he yelled at the bishops while holding a sign and carrying a copy of his own abuse report file.

By doing so, Delbos forced France to be aware of the scale of abuse at Bétharram: hundreds of young males abused, sexually or otherwise, by priests and staff at the Catholic school going back at least to the 1950s. More recently, after François Bayrou, became Prime Minister in December 2024, attention increased as, back in the 1990s, his son was a student there and his wife was the Catechism teacher at the school.

Beyond its direct implications, the case is also a stark reminder of how the French laws of secularism or laïcité have been ineffective to prevent abuse, while offering little or no actual help to the victims now facing the backlash of decades of violence against them in the name of God and country.

This is particularly relevant as Bétharram is not the sole case of violence, sexual or otherwise, in French schools. After Bétharram became a global scandal, alumni of other French schools, Catholic or not, are coming forward with similar accounts of violence, sexual or otherwise, inflicted as punishments to instill discipline.

Crucially, as one reviews the painful testimonies of survivors from Bétharram and other French Catholic schools, it is difficult to find a reverie of the Gospels. Instead, their accounts bear striking resemblances to the punitive systems that inspired French philosopher Michel Foucault’s 1975 masterpiece Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison.

Catholic heartland

Besides Bétharram, in the same region near the border with Spain, there are the Catholic schools of Saint-François-Xavier at Ustaritz (opens a story in French) in the French Basque Country; Notre-Dame du Sacré-Cœur at Dax (story in French), Notre-Dame de Garaison in the Upper Pyrenees (a story on the case in French).

In Paris, accusations emerged at the prestigious Stanislas Catholic school, as this story in French tells. Founded back in 1804, Stanislas is the epitome of elite Catholic education in France and Europe.

A key case was that of Notre-Dame Divine Bergère, a school owned and operated by the Society of Saint Pius X, SSPX, located at Gers, 55 miles or 80 kilometers north of Lourdes, the heartland of French Catholicism.

SSPX, an “order” of sorts not in full communion with Rome, was founded in Switzerland back in the 1970s by French bishop Marcel Lefebvre, who repeatedly blasted Paul VI for the changes to the Mass rituals, and ultimately challenged John Paul II’s authority.

He did so when in 1988 him and fellow rebel Brazilian bishop Antônio de Castro Mayer consecrated four schismatic priests as bishops. One of such bishops was notorious British Holocaust negationist Richard Nelson Williamson. All of them, Lefebvre, Castro Mayer, and Williamson died ‘out of the Church,’ according to their Catholic Hierarchy bios.

At their school in Gers, SSPX had to admit that violence was prevalent at Notre-Dame Divine Bergère, proving that, despite their claims about the “advantages” of their brand of Catholicism, exempt from the problems affecting the Church at large, abuse also happens in their establishments.

What is worse, believing themselves to be leaders of a “Catholic French Counter-Revolution,” they lack the controls that Rome has painstakingly developed over the last twelve years. SSPX promotes a sect-like culture, willing to challenge the authority of five Popes in a row. And when dealing with clergy abuse, sexual or otherwise, they claim to follow the rules of the arcane 1917 Code of Canon Law, without any amendment and with no actual recourse as they do not acknowledge the authority of the Pope or the Roman Curia.

Left to their own devices, their victims are in a darker place than victims of a diocese or an order in full communion with Rome. If you read French, follow the account at what used to be Twitter of the collective of survivors of the SSPX here or at their website.

It is not out of chance that they use Pius X’s name as a key feature of their core identity. Invoking Pius X’s Pascendi Dominis Regis, an encyclical from 1907, they have challenged the authority of the last five Popes, while promoting sect-like attitudes.

This is more relevant as the SSPX is active in the English-speaking world, with a large community of faithful in Kansas (see this story from 2020 at The Atlantic). In Canada, they boast about their presence in English and French-speaking communities, as their own Canadian website states.

In the Spanish-speaking world, they are active in Mexico and more so in Argentina, where they own the seminary of La Reja. More recently, they are able to gloat about their close relation with the current Vice President, Victoria Villarruel.

Carefully crafted images

Way before Bétharram became a scandal, seizing headlines all over the world, a majority of the French Catholic bishops were willing to acknowledge that the carefully crafted image of a Church intent on doing the right thing had concealed widespread clergy sexual abuse.

Their insight led them to commission a never-before-seen probe of the issue. They asked French policy eminence, Jean-Marc Sauvé, to be the lead researcher of a multi-pronged study. It included a very large sample poll, large enough to have enough cases for each French municipality and unprecedented access to the files of all but one French diocese and the vast majority of the orders in communion with Rome.

The fact that the diocese where the school of Our Lady of Bétharram sits was the sole dissenter, unwilling to come clean about what had been happening in its territory speaks volumes about the concerted efforts to keep abuse, sexual or otherwise, at Bétharram as France’s best-kept secret.

The diocese is that of Bayonne-Lescar e Oloron, an institution founded, by their claim, in the 4th century, way before France existed as a country, when that region of the world was still part of the Roman Empire.

That said, the episcopal records there only go as far as 1309, when Clement V appointed Pierre de Marenne. Clement V, born Raymond Bertrand de Gouth has the “merit” of being the first of the five Popes of the so-called Avignon Papacy, when Church and Crown were deeply associated in France, so much than the Pope moved his residency to French territory.

It is unclear if the current bishop, Marc Marie Max Aillet, was protecting himself or if he has been protecting the emeritus bishop Pierre Jean Marie Marcel Molères.

John Paul II appointed Molères back in 1986 as coadjutor, a hint that something was already in Rome’s radar then. On top of Molères’s appointment as coadjutor, there is the fact that Rome accepted the previous bishop’s resignation on the very day he reached 75.

The combination of the appointment of a coadjutor and an immediate acceptance of the resignation of bishop Jean-Paul-Marie Vincent is a sign people following the clergy sexual abuse crisis has learnt to understand as a symptom that something odd, to say the least, is happening at a diocese.

The story linked below from January of this year goes over Pope Francis’s forced resignations in the last two years of his tenure. Key among them was that of Dominique Marie Jean Rey, the emeritus bishop of Fréjus-Toulon, in the French Mediterranean coast.

Pope Francis forces out of office 30 bishops in two years

Rey’s case echoes Molères’s in more than one aspect. His succession was preceded by the appointment of a coadjutor, current head of the diocese bishop François Marie Pierre Touvet, who took over a few months after Rey’s 75th birthday.

What is worse, Rey’s troubles with Rome had to do with his relationship with groups in the French Catholic far-right, willing to go into the kind of sect-like behavior commonly associated with predatory cults.

Sadly, there is a wing of the Roman Catholic Church and French civil society unwilling to acknowledge the risks in Rey’s behavior. The split is clear when one goes over the two main French newspapers’ accounts of Rey’s resignation.

Le Monde stresses the many issues affecting the diocese of Toulon, including financial mismanagement. That detail is harder to understand when one takes into consideration that Rey is an economist trained at a French university. He had professional experience in that area before entering the seminary in the late seventies.

Conversely, Le Figaro dismisses the appointment of a coadjutor and Rey’s fast-tracked resignation as part of Pope Francis’s revenge on the Rad-Trads or “Tradis”, as the French newspaper calls them, while praising Rey’s ability to bring his diocese back to life.

In any case, as far as Bayonne is concerned, it would be during Molères’s tenure as bishop (1986-2008) that the bulk of the abuse reported these days happened, so there is a rather large chance that Aillet’s decision to keep the diocese’s files secret was the byproduct of several decades of mishandling of the diocese of Bayonne.

Karmic ironies

Ironically enough Rey consecrated Aillet as bishop back in 2008 when Benedict XVI appointed him to Bayonne. The other prelates consecrating Aillet were Molères and Cardinal Jean-Pierre Bernard Ricard, then archbishop of Bordeaux.

Another irony lies in the fact that, despite the careful design of the Sauvé Report, the care the many researchers put into providing the most accurate report of the extent of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church to date, the findings were under the fire of the right wing of the French and European Catholics for “overstating” the reach of the crisis.

However, on social media, it is possible to trace the French and European Catholic right’s condemnation of Sauve’s care. French identitarians, Italian sovereigntists, and supporters of Vox and other Spaniard right-wing groups found it intolerable his choices for the committees.

If you read French, you can over the kind of vitriolic responses the French bishops got from angry social media accounts criticizing Sauvé’s decision to include in the committees behind the report, among many others, a physician who identifies himself as Muslim, a theologian who identifies herself as non-Catholic, and—the absolute abomination—a “feminist sociologist,” whom they thereby implicated, in the usual tone of Catholic sect-like groups as “anti-Catholic.”

The last months of 2021 were a relentless parade of accounts linked to factions of the European identitarian right, attacking the French bishops decision to commission a credible study, unlike the farce their colleagues south of the Pyrenees would commission months later, in 2022.

In Madrid, the Spaniard bishops asked Javier Cremades, a full member, numerary of the Opus Dei, as they call themselves, to come up with a semblance of a report, as the “Credibility” section of the story linked after this paragraph tells.

Vatican admits sexual abuse undermines the Church’s credibility

Sauvé’s critics got a karmic response of sorts when, less than two years after releasing the Sauvé Report, the very foundations of the French Catholic Church were, once again, put under the severe stress when details about Abbé Pierre’s abuse came to light.

Abbé Pierre, a hero of the French Resistance to German Nazi occupation, a larger-than-life figure willing to go the extra mile for French and European homeless people, able to spearhead a global movement in his name. He was a priest and champion of social justice, turned out to be a sexual predator in Mexican Marcial Maciel’s or Argentinean Julio de

Hero, priest, and sexual predator: the story of Abbé Pierre

A previous installment of this series, linked above, dealt with Abbé Pierre’s case, while several installments of the same series have used one of the Sauvé Report’s key findings, an estimate to calculate the actual, current, number of victims of clergy sexual abuse.

An estimate of the number of victims of sexual abuse in the Church

Pervasive violence

While the focus has been over the last few years on Catholic institutions in France and elsewhere, it is important to note that the public system in France had already gone through a reckoning in previous decades. Of the publicly available data, it is possible to track down information about different types of violence going back to 2008.

This French-language page hosts all the available official reports starting in 2009, while the most recent report, from 2024, is available here.

The earliest report, from 2009, the so-called Repères et Références Statistiques (something close to Statistical data and references, available as a French PDF on the same government page as all the previous reports cited in the previous paragraph), states, at p. 56:

- Over the 2007-2008 school year, public secondary schools recorded 11.6 acts of serious violence per 1,000 students. These serious incidents are primarily personal assaults (81 percent), manifesting equally as verbal abuse and physical assault. Invasions of privacy, sexual violence, racketeering, “happy slapping” (recording a physical assault of a person using a mobile), and hazing, reported to school officials, are relatively rare. Relatively less frequent—15 percent of serious incidents recorded—are property attacks, consisting mainly of theft and damage to school premises or equipment. Finally, four percent of the reported incidents are related to the security of the school’s premises, half of which involved the use of some drug.

So, 18 years ago there was already evidence about the extent of the violence in French schools. However, it was not until some of the survivors from Bétharram called out what had been happening there that there was an acknowledgement of how pervasive violence has been in the Catholic school system in France.

A legacy of the many iterations of the «Me Too» movement, with its new dynamics of a global public opinion fueled by the Internet, the growing conscience about the reality of sexual abuse and its pervasive long-term effects on the health, education, and professional performance of those affected by abuse, made the reports from Bétharram credible.

What comes as a surprise at this point is not abuse as such. It is François Bayrou’s defense of his alleged ignorance about what was happening at the school where his son was a student, where his wife used to teach catechism, at a time when he was the French minister of Education while, given the peculiarities of the French political system, a local government official, an authority, in the region where Bétharram is located.

Major Leagues

His defense has been in full display for the last three months or so. There was a legitimate expectation that he would come clean with a credible explanation of his role in this case, especially what was his knowledge of the issue, during the May 14 hearing at the French National Assembly.

Furthermore, his hearing was preceded by testimonies from former public officials, former professors, alumni, and other parties who said they were aware and at least three of them offered a sworn testimony about how they informed Bayrou about the abuse at the school.

They claimed having done so at the time Bayrou was minister of Education of the national government. He held that position from March 30, 1994, through June 3, 1997, during the presidencies of François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac, as part of the governments of prime ministers Édouard Balladur and Alain Juppé.

Given that French politicians are able to serve concurrent offices at the National, regional, and local governments, he has been, since the late 1980s, a key political figure in the French Pyrenees and France at large, having occupied almost all elective offices except that of President of France.

He used to be a member of the now disappeared Union for the French Democracy (Union pour la démocratie française), that was dissolved in 2007, when Bayrou became leader of the smaller Democratic Movement (Mouvement democrate), known in France as Modem.

His return to the major leagues of French politics is more the byproduct of the erosion of the old parties and the extreme fragmentation of parties and movements there, than the function of his or his Modem party’s popularity. Currently, they hold 33 out of 577 seats in the lower house of the French Congress and four out of 248 seats in the Senate.

He became Prime Minister after Michel Barnier’s short-lived “100 days” government (September 5 through December 13, 2024) fell. He became the prime minister as part of the Ensemble (Ensemble pour la republique), a confederation of parties. As part of that coalition, Bayrou controls 159 out of 377 seats in the lower house, a bit over one-fifth of the total number of MPs.

As it happens in Canada, the French Prime Minister does need to be an elected member of the lower house of the National Assembly, he only needs to gather enough votes to be asked by the President to form a government.

Political maneuvering

Through Ensemble, Bayrou was able to built a government under Emmanuel Macron’s Presidency, but in constant risk of facing a similar fate to Barnier’s, as proven by the repeated calls to face confidence votes in the National Assembly.

Last Wednesday, June 4, Bayrou faced the latest challenge to his mandate. Although the opposition was unable to gather enough votes, questions remain as to his ability to manage repeated calls for his resignation, enhanced by his tone-deaf claims that he was fully unaware of what was happening at Bétharram.

Despite his ability to overcome the confidence vote, fact is that there is a deficit of trust in his handling of the crisis at Bétharram and in his overall performance as Prime Minister.

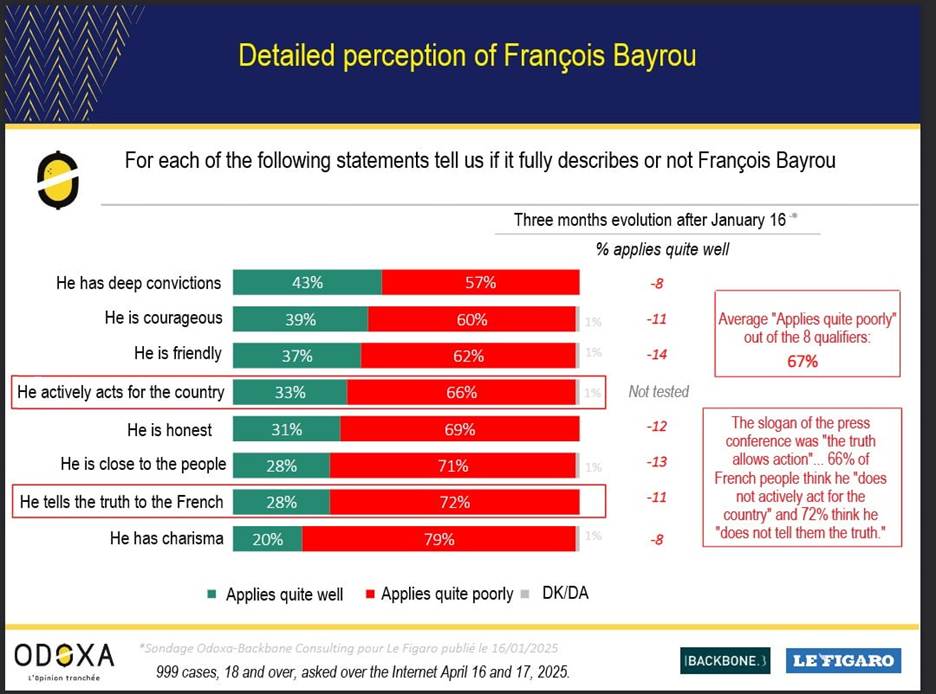

A month before his hearing, Odoxa, a French pollster published a poll done over April 16 and 17, 2025. A graph from that poll appears after this paragraph. The key take away from it is the French public opinion’s low trust and negative opinion of Bayrou and his performance as Prime Minister.

More than two thirds of French persons 18 and older have a negative opinion of Bayrou. It is clear, if one goes over the full poll from Odoxa, available as a PDF here only in French, that Bayrou is not the sole recipient of French society’s distrust in its political leaders, but should that come as a consolation for Bayrou?

That is precisely why it is more dangerous for Bayrou, a self-described practicing Catholic, devoted father, and political chieftain of his hometown, to stick to the jingle about knowing nothing about abuse happening in his own hometown, at the school where his son was a student, and his wife used to teach Catechism.

He can do so, as the statute of limitations has prescribed for most of the atrocities perpetrated in Bétharram by the end of the 20th century, but it is hard to translate that political calculation to something in the Catholic Church’s doctrine or even harder in the Gospels.

In that respect, the crisis in Bétharram confirms many of the systemic patterns of systematic denial and cover up, a key aspect of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, that usually leads to the also systematic gaslighting of the victims and their families. When that is not enough, then comes the harassment and threats or, conversely, the turning of the tables, rendering the Church as the victim of a vast conspiracy to destroy it.

In following those patterns, Bayrou dismisses the testimonies of one former judge, one former policeman, and one former professor who explicitly told the Congressional probe that they informed Bayrou, then minister of Education about the abuse.

Spreading the guilt

Far from acknowledging his own mistakes, Bayrou tried to “share the guilt” with other French politicians. His target was Socialist former minister and former MP Ségolène Royal. She was an official at the French national education authority by the end of the 20th century.

While she was very able to call out Bayrou’s tactics, similar to those of Richard Nixon at the height of the Watergate scandal, she was unable to provide a “smoking gun” of sorts. That is to say, so far, there is no irrefutable evidence that Bayrou or the many different authorities in the French government were aware of what was happening at Bétharram or, for that matter, at any other private or public French school by the end of the 20th century.

The fact that France, as many other countries started to pay attention to the issue of violence, sexual or otherwise, during the first decade of this century, proves that there was some ability of the French political class to acknowledge that something was happening in the public schools, as reflected in the first digitally available volume of Repères et Références Statistiques, from 2009, cited before.

However, it is hard to go back, and it seems impossible to prove with a document that Bayrou knew what was happening at Bétharram. That has been his defense, and it looks as if will remain so.

For the time being, the Bétharram crisis continues to unfold, serving as a stark reminder that the wounds of abuse, left unaddressed, fester across generations and institutions.

It must be noted that Bétharram is not relevant only for what happened at France, at the actual site where the school has been operating for more than a century. Behind the school, there is an eponymous religious order, active, with schools all over the world.

Even if victims of violence in France have now new venues to achieve a measure of justice, that is something not readily available for victims of other members of the order behind Bétharram.

The Argentine Network of Survivors of Clergy Sexual Abuse (opens link in Spanish) is actively seeking to gather as much evidence as possible to detonate similar processes to the one currently unfolding in France, as to offer survivors a chance to find justice.

Next week, Los Angeles Press will publish a translation of a very detailed assessment of what has been the crisis at Bétharram and its implications for the French and global Catholic Church by French Catholic priest Camille Rio. He published back in December 2024 with us a English- and Spanish-language assessment of the report issued by the Foreign Missions order with which he has been associated for several years.

Secrecy and omerta behind sexual violence at the Foreign Missions

His assessment of the crisis at Bétharram goes deeper into the global nature of the order behind the school and what needs to be done to actually address the crisis in France and elsewhere.

The true measure of a Church calling itself Christian cannot be the success at the carefully crafted denials or tactical deflections. The key lies on whether or not it addresses the need to protect all its faithful and to deliver justice to those who have suffered in silence for far too long, regardless of technicalities.

A mirror for all to look at

Until that is achieved, Bétharram remains a mirror, reflecting not just the struggle of French survivors of clergy sexual abuse, but a global challenge to find justice for the survivors.

Deep in the cracks of this case there is also a cautionary tale for those overemphasizing Church and State separation as the sole or main guarantee to avoid the excesses of organized religion.

It would be hard to imagine a more radical model of Church and State separation than French laïcité, as set in the early 20th century and reaffirmed every time its Constitution or secondary laws have been reformed.

It is clear that models of Established Church as the Church of England in the United Kingdom or the Catholic Church in Peru, Colombia, and other Latin American republics also offer no guarantees on the issue. They actually aggravate abuse, as the Peruvian Sodalitium case proves.

However, the fact that countries with alleged secular states as France or Mexico are on the record as having offered near-to-perfect conditions for predators as Abbé Pierre or Marcial Maciel, should make it clear that there is a need to address clergy sexual abuse without falling for oversimplified intuitions.

French newspaper Libération with news of Abbé Pierre serial abuse, July, 2024.

Only in France, by far one of the more robust and reliable judiciary systems in Europe, up until 2021, 90 percent of rapes reported never went to trial. The rulings of the Pelicot, Le Scouarnec, and Depardieu trials offer hope about the ability of the French system of justice to improve, but survivors from Bétharram and other schools, who were attacked in the 20th century have little or no chance to find that kind of relief.

The French episcopate has been willing to acknowledge that fact and the devastating effects of their Church traditional approach to deal with clergy sexual abuse. So there are ways for French survivors to access some measure of justice, as Delbos himself was able to do, and as this story at the Sisters Global Report site tells, but there are still notable deficits in other countries, with former students of other schools owned and operated by the order at Bétharram. Hence the interest of the Argentine Network of Survivors, as an example.

The Colombian mirror

Over the last week, Colombian Archbishop Gabriel Ángel Villa of Tunja, used the Sunday Mass in his diocese to challenge the judiciary’s ruling ordering the Catholic Church to release data about their priests’ appointments to perform their duties.

His message follows a rather incendiary piece published over that diocese’s website by local priest Raúl Ortiz Toro (available only in Spanish here), who bitterly complains about the ruling.

To make matters worse, Ortiz Toro’s bitter complain was adopted as a war cry by Colombian priests active over social and amplified by their loyal faithful obsessed with the idea of judiciary overreach, a blow of sorts, to attack the Catholic Church on behalf of so-called “woke ideology.”

Instead of accepting their Church’s and their own mistakes to seize the chance at restoring trust among the faithful and survivors, the Archdiocese of Tunja renders itself again as victim of a wide conspiracy. Ultimately, the ruling only forces them to do what is readily customary in other countries: knowing a priest’s professional assignations, where and for how long.

That is something already available for the bishops at a global scale over websites as Catholic Hierarchy or GCatholic, but similar data for priests is hard to gather. The difficulties to access said information facilitate the use of the “geographic solution,” that is to say, transferring priests without a record, a proof, of where and if he was transferred.

The Oblates and the “geographic solution” to clergy sexual abuse

Even some dioceses in Argentina and Mexico have achieved timid improvements on this issue. Why the Colombian archdiocese of Tunja, and given their behavior over social media, other dioceses of that South American country are betting once again on rendering themselves as victims?

A genuine path forward demands unfettered transparency, a commitment to systemic reform including accountability and specific punishments, both within the Catholic Church and from the civil authorities when dioceses or orders do not comply with specific goals or benchmarks.