A Priest's Troubled Path

Abuse allegations followed Rev. Louis Miller through career

By Andrew Wolfson

awolfson@courier-journal.com

The Courier-Journal

June 23, 2002

http://www.courierjournal.com/localnews/2002/06/23/ke062302s230487.htm

[Note from BishopAccountability.org: A survivor's name has been redacted

from this article at the survivor's request.]

To adults like Anna Dale Ernest, ''Father Lou'' was a super priest who

could get things done.

From the church roof to the gym floor to the parish parking lot, if something needed fixing, replacing or paving, the Rev. Louis E. Miller took care of it.

''He worked like a dog and always seemed to have a smile on his face,'' said Ernest, a former parish council president at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Church, the fourth and final church where Miller was a pastor or associate.

|

| Photo illustration by Mike Covington. [One survivor's name has been redacted.] |

Seven years after Miller left St. Elizabeth, he was still so admired in the parish's working-class Louisville neighborhood that in 1997 he was named Schnitzelburg's ''No. 1 Citizen.''

His reputation with certain children was something very different.

He was a predator, they now allege.

From the playground to the locker room, in hallway closets, hospital rooms and the church sacristy and even at his family's gatherings, Miller is accused in lawsuits of molesting 57 children in four parishes and on the watches of three archbishops.

Miller, 71, who retired in March after Archbishop Thomas C. Kelly removed him from his last assignment, declined to comment for this story. Miller, who now lives at a retirement community for priests in Louisville, has not been charged with any crimes in connection with the dozens of lawsuits filed since April 19 that accuse him of misconduct but name the Archdiocese of Louisville as defendant.

Many adults who knew him as a friend struggle to reconcile the accusations with the person who would camp by the bedside of the sick and dying and stir the turtle soup at the parish picnic.

Dale Depoyster, who headed St. Elizabeth's parish council in 1986 and 1987, said Miller was a strong leader: ''He was a caring man, but also a man's man -- a tough character who didn't come across as a pushover.

''He followed the rules and he did all the priestly things right.''

But the accusers -- most of them now middleaged men -- paint a portrait of a man who is alleged to have stalked children, using circumstance and the authority of his collar to cull victims for his sexual gratification.

[photograph redacted]

|

| [Name redacted], who said Miller sexually abused him when he was a sixth-grader at Holy Spirit School, said the priest seemed "a pathetic figure" when [Name redacted] met with him in 1997 to confront him. Photo by J.T. Lovette. |

[Name redacted], 52, who attended Holy Spirit School in the early 1960s

and has filed a lawsuit claiming Miller sexually abused him as a sixthgrader,

wrote to Miller in 1997 in advance of a therapeutic confrontation with

the priest arranged by Kelly:

''I remember most distinctly the feeling of dread when I was called to see you for any reason . . . I remember my throat beginning to close in fear and a feeling of powerlessness. I felt like I . . . was completely without protection. This gave way to feelings of hopelessness since . . . the church was completely behind you with all of its power.''

Despite the dozens of lawsuits that implicate Miller, few families say they reported him to their church or to the archdiocese at the time of the alleged abuse, and only one person -- Miller's niece, Mary C. Miller -- said she went to police about it.

|

| Dr. William Handelman held a photo of himself at 10 or 11. He said that he told his parents the Rev. Louis Miller had abused him, and that several parents complained to Holy Spirit's pastor until Miller was transferred in 1961. Photo by Dirk Shadd. |

Eight plaintiffs, however, say they or their parents did tell a priest, principal or the archdiocese about Miller's alleged abuse. If the plaintiffs' recollections are accurate, Miller was reported at least once in each of the four Louisville-area parishes where he worked.

An examination by The Courier-Journal of Miller's transfers and what the plaintiffs have alleged in suits and interviews indicate the archdiocese was or could have been aware of sexual complaints against him in four instances when it moved him out of parishes.

The archdiocese doesn't record the reason for transfers of priests, so there is no record of why Miller was moved, said Cecelia Price, its spokeswoman.

|

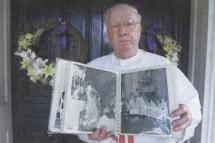

| In 1992, the Rev. Al Hartlage held photographs taken during his ordination in 1956. Hartlage, now retired, was ordained the same day as Miller and said of him, "He has always been my friend." Photo by Durell Hall Jr. |

The archdiocese has declined to comment on the lawsuits. Brian Reynolds, its chief administrative officer, said questions about Miller's performance as a priest were better left to people in the parishes he served.

A devout family

Born on the last day of 1930, the fourth of eight children, Louis Edward Miller grew up in the West End in a devoutly Catholic family whose life revolved around the old St. George parish.

|

| Miller was hugged in 1980 by a woman after baptizing her child at St. Elizabeth of Hungary, where he served from June 1976 to January 1990. Nine people have accused him of abuse in connection with his time spent there. Courier-Journal file photo. |

One of his aunts was a nun, as was a cousin. Two more cousins were priests, including the Rev. John Weyhing, later dubbed the ''Street Priest'' for ministering to the down and out at taverns and shelters.

Miller's father, Theodore J. Miller Sr., worked for the L&N Railroad for years, then ran the old Miller Hardware store at 26th and Market streets. Miller's mother, born Eleanor Erhart, tended to the children -- seven of them boys.

The family squeezed into a 1,500 square-foot home in the 1800 block of Gaulbert Avenue built five years before Miller was born. They never had much money, recalled the priest's sister, Eleanor Sanders, who now lives in Evansville, Ind. To make ends meet, they baked bread and raised chickens and pigeons in their back yard.

|

| The Rev. Louis E. Miller worked at four Louisville-area parishes before retiring in March. |

Young Louis had no talent for sports but liked to hunt, fish and gig for frogs, Sanders said. She said she didn't remember him having a lot of girlfriends; instead, he hung out with his many cousins.

''He was never a wild one,'' she said. ''He was pretty serious.''

After three years at the old Flaget High School, he transferred to St. Mary's College in Kentucky to finish high school and at the same time start his seminary training. He then ''took his theology'' at St. Meinrad in Southern Indiana, according to a profile published in the archdiocesan newspaper, The Record, before he was ordained on May 26, 1956.

The first accusation

As he prepared for ordination in 1956, there was nothing that suggested the serious and studious Miller would be anything but a good priest.

Fellow seminarians at St. Meinrad say Miller was hard-working and well-liked. ''He has always been my friend and all I have ever known of him is good,'' said the Rev. Albert Hartlage, who was ordained the same day as Miller and is now retired.

The first accusation against Miller dates to the early 1950s. In one of the lawsuits filed last month, Miller is alleged to have sexually abused a boy while working as a counselor at Camp Tall Trees in Meade County, Ky.

The archdiocese said it was unable to verify that Miller worked at the camp.

Miller's first priestly assignment was at Holy Spirit Church and school as associate pastor.

So began a career in which he is alleged to have abused 56 children -- four girls and 52 boys.

At Holy Spirit, where he worked until 1961, Miller is alleged to have molested 24 students, including 14 members of the class of 1963 who were in sixth grade at the time, according to lawsuits filed in Jefferson Circuit Court.

The mothers of James B. Corcoran Jr. and William Handelman say their husbands complained to the pastor, the Right Rev. John Vance, about Miller. Timothy L. Baker also said his father complained to Vance.

Years later, Miller would say in a deposition that he wasn't forced out of Holy Spirit. ''I was due to leave, so I left.''

Miller was transferred to St. Athanasius parish, where he worked in 1962 and 1963. In lawsuits filed this year, accusers contend Miller preyed on six children there.

Michael A. Gnau and William G. Brown both say their parents complained to the pastor, the Rev. Francis Bossung. Gnau said his father complained about a second alleged incident, and Miller was reassigned to SS. Mary & Elizabeth Hospital.

At the hospital, where Miller served the next 10 years as chaplain, two men allege that he abused them when they were childhood patients. Another has alleged Miller molested him when he was a visiting altar boy.

After a decade there, the archdiocese moved Miller to what would become his first assignment as a pastor, at St. Aloysius in Pewee Valley.

At that parish, where he was an associate and then pastor from 1973 to 1975, he is alleged to have abused a dozen children.

Joseph Thornberry, whose son John was a student at St. Aloysius, said he complained to the principal, two other priests and the archdiocese that Miller had abused his son.

About the same time he was at St. Aloysius, Miller is alleged in suits to have abused a niece and a nephew in settings outside the church, including family gatherings.

Archbishop Thomas McDonough moved Miller from St. Aloysius in November 1975. Miller had no assignment for four months and then was given two temporary assignments at St. Ann's in Howardstown and Our Lady in Hodgenville.

In June, McDonough assigned Miller as pastor at St. Elizabeth of Hungary, where he worked from 1976 to 1990. While at the parish, Miller is alleged to have molested nine more children.

In December 1989, Miller went to Archbishop Thomas C. Kelly and told him that a former student at St. Elizabeth, Mark Delmenhorst, and his parents had complained to him that Miller molested him 12 years earlier, the archdiocese has said.

Delmenhorst filed suit against Miller, the archdiocese, St. Elizabeth and the United States Catholic Conference in 1990. The archdiocese vigorously defended itself, arguing in court papers that Delmenhorst, despite being only 15 at the time of the alleged abuse, contributed to his own injuries.

The suit was eventually settled out of court.

Miller worked most of the next 12 years at Sacred Heart Village, a retirement home.

The archdiocese has defended the decision to allow Miller to continue to function as a priest after his work at St. Elizabeth, noting that medical professionals advised that with treatment, there was no reason to think Miller would pose a danger to anyone.

Reynolds, has noted that there are no allegations of abuse by Miller after he was placed on the restricted ministry.

In March, Miller opted to retire after Ronald T. Landry, 54, who lives in South Florida, and others complained directly to the archdiocese that the priest had abused them.

Pair say they complained

The archdiocese has maintained that it has found no record that it received sexual abuse complaints against Miller during the 1960s or 1970s.

But John and Joseph Thornberry said in interviews they didn't know how that could be true.

John Patrick Thornberry, 40, who in 1975 was an eighth-grader at St. Aloysius School and an altar boy and lector in St. Aloysius parish, said that one fall day that year, Miller had him pulled from class, supposedly to run an errand. Instead, Thornberry told the newspaper, the priest brought him to the rectory basement, where Miller pulled down his own pants, put the boy's hand on his penis and forced him to masturbate the priest until he ejaculated.

Joseph Thornberry said in an intervew that on that day, his son came to him 90 minutes after his bedtime and said, '' 'Father Miller bothered me today.' ''

''My wife and I were stunned,'' the elder Thornberry said. ''We were angry.''

Joseph Thornberry said he reported his son's allegations to the principal and two priests, both of whom said they would take care of the matter and see that Miller wasn't left alone with children.

Joseph Thornberry, a retired tooland-die maker for General Electric, said he also called the archdiocese and demanded that Miller be removed from the parish. He said he doesn't remember whom he spoke with, but one week later Miller called and asked if he could come to the family's house to talk.

''We didn't know what he would do,'' Joseph Thornberry recalled, ''so my wife sat upstairs in our bedroom with a loaded .22.''

''He said he wanted to stay in the parish until after Christmas because he'd put in a lot of work on the school's Thanksgiving and Christmas programs,'' Joseph Thornberry said. ''We said no.''

Joseph Thornberry said Miller conceded he'd had '' 'a little contact' with John but it was one of those 'brief things' and it wouldn't happen again.

''He said he wasn't a pedophile and wasn't a homosexual,'' Joseph Thornberry said. ''He apologized and said he hoped John was all right.

''I told him, 'I ought to just kick you in the crotch and call the cops,' but I didn't.'' He said his son didn't want to see Miller punished.

John Thornberry, who now lives in Colorado, where he's a theater producer, said Miller also later requested a meeting at the school with him.

It took place in the cafeteria, John Thornberry said, so others would be present.

''I don't remember much about the conversation,'' John Thornberrry said, ''except that he asked, 'If I didn't like what was going on, why didn't I say stop?' ''

Two weeks later, the Thornberrys say, Miller was moved from St. Aloysius parish -- before the holiday programs.

John Thornberry said he didn't find out until years later that Miller had been assigned to another parish. He said he's forgiven Miller, but not the archdiocese.

''I think it was absolutely criminal that he was allowed to go anywhere,'' John Thornberry said.

From [Name redacted]'s 1997 letter:

''It is hard for me to think about the physical experiences but I believe it is important to do so. I remember one particularly difficult time during server practice when there were five or six of us boys present. We were all in the sachristy. You called on each of us to stand in front of you with our back to you and facing the others. You then would take our hands behind your back and rub your penis with them while you conducted the class. My own experience of this was . . . terror and paralysis . . . in front of my peers. They knew what was happening but couldn't acknowledge it in any way and I couldn't express my own feelings because of fear of retribution from you. This experience left me with a feeling of deep shame. . . .''

Relatives' allegations

Many of Miller's accusers recall that he was friendly and helpful to their families.

James C. Hess, now 29, who contends in his lawsuit that Miller molested him at St. Elizabeth between 1983 and 1988, recalled that Miller came to his house for a party to celebrate his first Communion and drove Hess' father to the hospital when he had a heart attack.

''I thought the world of him,'' Hess said, until the alleged abuse began.

Miller also allegedly preyed on his own family members, according to one suit filed in 1999 by a niece, Mary C. Miller, and another on June 7 by a nephew, Mark A. Miller Sr.

Mary C. Miller alleged that at two family gatherings when she was 10 years old, Miller twice kissed her on the mouth with his mouth open, and five years after that, forced her to hold his penis while he sat next to her on a couch.

Louis Miller's sister-in-law, Mary Jane Miller, said in a deposition that none of the allegations against the priest were ever discussed in the family as a group.

''It's an old German family,'' she said in a deposition given last year in Mary C. Miller's suit, which was settled. ''You circle the wagons. Nobody talks about it.''

Neither woman would agree to be interviewed for this story.

But Louis Miller's nephew, Mark A. Miller Sr., told the newspaper that ''as long as I can remember, the Miller family literally worshiped my uncle. Maybe it was the times in which they grew up . . . or because he had a very powerful charisma.''

Known for good deeds

Colleagues at St. Elizabeth and other parishes said they saw no evidence that Miller was doing anything wrong.

The Rev. Bernard Craycraft, who is retired, said he visited every family in the parish when he succeeded Miller at St. Athanasius -- and none had any complaints about Miller. Patrick Whelan, who worked with Miller at St. Aloysius before leaving the priesthood, said he saw no evidence of wrongdoing.

At St. Aloysius, Miller blacktopped driveways, built sidewalks, and fenced, mowed and marked the parish's nearly abandoned cemetery. He oversaw the renovation of an an old coal cellar, enlisting Boy Scouts to clean it out and parish members to rewire and air-condition it.

At St. Elizabeth, he took on an even bigger project, the total renovation of the church, recalled then-Deacon Kenneth Osborne.

''He was always on the go,'' Osborne said. ''I considered him almost a workaholic. All indications were that he was a good priest.''

The Rev. Paul J. McGuire, a Wisconsin-based scholar who lived in the St. Elizabeth rectory with Miller from 1986 to 1989, while McGuire was Bellarmine University's campus minister, said Miller's conduct was ''absolutely beyond suspicion.''

Experts on sexually abusive clergy, while not commenting on the Miller case, say that the worst offenders often are the most stellar pastors, and that their good deeds can provide a cover for their misconduct.

''They take their ability to manipulate people, the same skills they use for good, and use them for bad,'' said Patrick Schiltz, who has defended Roman Catholic dioceses against hundreds of claims and is now dean of St. Thomas School of Law in St. Paul, Minn.

''You can't sexually abuse 100 children unless you can get 100 children to trust you and the parents of 100 children to trust you.''

Minnesota lawyer Jeff Anderson, who has litigated more than 600 child sexual misconduct cases against Catholic clergy, said predatory priests are often charismatic, seemingly kind and effective.

''They use their charm and and the power of their collar to serve their own insidious needs,'' he said. ''If they were stumbling and bumbling, they would be unable to covertly seduce and prey on their victims.''

Visiting the sick, comforting the dying, anointing the dead and other priestly functions can provide a cover for sexual misconduct by making allegations hard to believe when they surface, said Jason Berry, co-author of ''Lead Us Not into Temptation: Catholic Priests and the Sexual Abuse of Children.''

From [Name redacted]'s 1997 letter:

''More important . . . perhaps than any physical violations, . . . were the abuses of your power and authority and your betrayal of the trust and confidence that our parents gave you. You became an evil role model in our lives and a symbol of deceit and hypocrisy in the world. I can say without reservation that your influence turned me completely against the Catholic Church and everything that institution represented.''

One man seeks healing

After decades of therapy and selfdoubt, [Name redacted] decided in the early 1990s that the only thing that would completely heal him was to publicly expose the priest he said had abused him at Holy Spirit.

On Oct. 19, 1992, [Name redacted] wrote Kelly, saying he intended to write a letter to The Courier-Journal about what happened to him and to publicly name the priest.

''So many people -- so many children are victims,'' including ''many other boys at Holy Spirit,'' [Name redacted] wrote. ''We must do everything we can to stop the cycle of abuse. One important way is to try to help heal every survivor by sharing our stories to expose the abusers and understand what causes people exploit children this way.''

[Name redacted], a teacher and counselor for [Name redacted], the California-based [profession redacted], told Kelly he was contacting him in advance only because the archbishop knew his parents well and they respected him.

A week later, Kelly wrote back, expressing deep sorrow for [Name redacted]'s pain and begging forgiveness on the part of the church, but saying there might be an alternative ''to the public course of action you contemplate.

''While I recognize that this is a matter for you to decide, I am also anxious to spare your parents the pain of public disclosure,'' Kelly wrote.

''Nonetheless, I freely acknowledge that therapy and counseling may well have brought you to the point where such disclosure is necessary for your own well being, and that I would regard as having the highest priority in a matter that has been a source of so much pain to you for so many years.''

[Name redacted], 52, who lives in Northern California, said in an interview that he believes Kelly sincerely was trying to help him but also was trying to protect the archdiocese from bad publicity. ''He worked the guilt angle on me,'' [Name redacted] said.

The archdiocese confirmed the authenticity of the letters but declined to comment on them.

[Name redacted] said Kelly agreed that the archdiocese would pay the cost of some of his therapy and, several years later, to set up a meeting between [Name redacted] and Miller.

In November 1996, Kelly wrote to [Name redacted] that Miller had agreed to the session, ''even though he feels great remorse and pain about the past.''

Before their meeting on May 6, 1997, [Name redacted] said, he wrote his letter to Miller to clarify his thoughts:

''. . . Past encounters with you deeply affected my personality and my experience of myself as a man. My introduction to sexuality was altered dramatically by these encounters. . . . I have spent my whole life seeking . . . some kind of appropriate initiation into manhood where I could regain my own personal power and self-respect. . . . I look forward to seeing you and addressing these matters with you in person.''

They met in the office of Miller's therapist, Dennis Wagner, who sat in on the session. He declined to comment.

Miller ''asked me to forgive him,'' [Name redacted] said recently in an interview.

He said Miller ''acknowledged he had acted improperly with me and other children, but when I asked him about specific experiences, he said he couldn't remember.''

[Name redacted] said he had remembered Miller as a powerful presence, but now he seemed a pathetic figure. ''He seemed in fear that I was going to punch him out.

''I wasn't,'' [Name redacted] said. ''I just wanted to take my power back -- and it worked.''

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.