Study Reveals Vast Scope of Priest

Abuse The clergy sexual abuse scandal reached far more broadly across the Los Angeles Archdiocese — and put far more children at risk — than has previously been known, according to a Times study that examined the records of hundreds of accused priests. Although the sexual abuse scandal has been the subject of more than 560 court claims and a report by the archdiocese, basic information on the dimensions of the problem have remained sketchy. The Times analysis is the first to quantify the breadth of the scandal in the archdiocese.

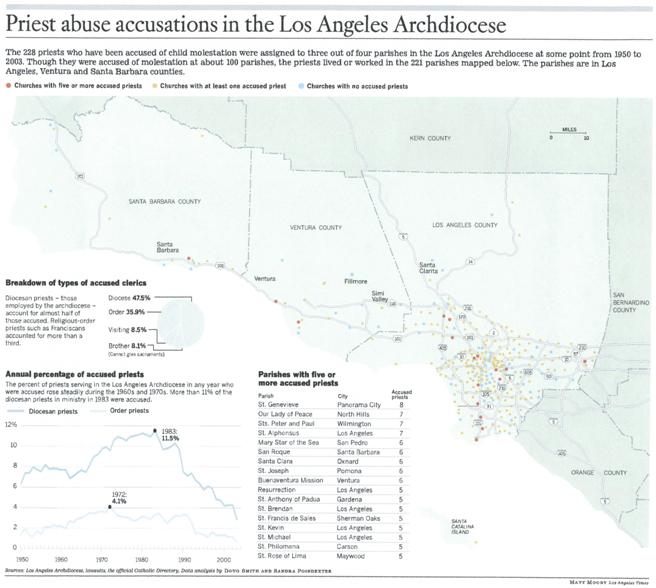

Molestations have been alleged at roughly 100 parishes. But because the accused priests moved around the archdiocese on average every 4.5 years, the total number of parishes in which alleged abusers served is far larger — more than three-fourths of the 288 parishes, according to the study, which examined records back to 1950. The affected parishes were in neighborhoods of Los Angeles, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties both rich and poor, suburban and urban, some predominantly white and others with African American or Latino majorities. The study does not support the contention made by some critics of the church that problem priests were dumped into poor, Latino and African American communities. Based on the allegations, the number of abusive priests peaked in 1983. More than 11% of the diocesan priests — those who worked directly for the archdiocese, rather than for religious orders — who were in ministry that year eventually were accused of abuse.

[Note: This map with graphs is also available as a PDF,

and the same data is presented as a statistical

summary The widespread placement of alleged abusers raises the question of whether molestations may have gone unreported at many parishes. J. Michael Hennigan, the lead defense attorney for the archdiocese, said he thought the immense publicity about clergy sexual abuse had drawn out most victims. But David Clohessy, executive director of the victim support group Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, said he believes many victims remain unknown and unwilling to pay the emotional price for stepping forward. There's "a great misconception" that when one victim comes forward, others will follow, Clohessy said. In reality, he said, "the next 15 victims breathe a sigh of relief" that someone else is shouldering the burden. Cardinal Roger M. Mahony, who has led the archdiocese since 1985, declined to comment on The Times study. Hennigan said the church never knowingly put children at risk. Archdiocese officials routinely transferred priests, especially early in their careers, he said. In at least eight cases, the archdiocese allowed priests to remain in ministry after receiving information about their alleged sexual interest in minors. Hennigan said all priests who were transferred after complaints received psychological evaluation and treatment before they were returned to parishes. Mahony has since removed them all from ministry. Church officials have said their policy toward alleged abusers evolved over time into the current "zero-tolerance" stance. But, Hennigan added, "I am not aware of a single instance in the archdiocese in which a credible allegation was made about sexual misconduct and the solution was to simply transfer him to another parish." Since the archdiocese was confronted by a flood of lawsuits 2 1/2 years ago, Mahony has declined litigants' requests to tell parishioners if accused priests ever worked or lived at their churches. Mahony also has fought release of confidential church files containing complaints, correspondence and priest assignments. The files would detail what diocesan officials knew about the allegations and what they did about them. The cardinal and his lawyers argue that releasing the data would violate the privacy of individual priests and the church's constitutional right to keep certain religious matters confidential. Lawsuits for the most part have been filed against the church, rather than individual priests, and in some cases identify the alleged abusers only as John Does. The parishes where they served during the accusations are not always named in the suits. The litigation has been in closed-door mediation almost since the cases were filed, further limiting public airing of the facts of the scandal. Because the accusations are too old to prosecute and the church insists it intends to settle civil complaints out of court, most molestation complaints may never be proved or disproved. To prepare its study, The Times tracked the assignments from 1950 through 2003 of 228 priests who have been named by plaintiff's attorneys or identified by the archdiocese as the subject of abuse complaints. The study does not include 19 priests whose names were released by the church on Tuesday. It also does not include as many as 30 priests whose names the church has withheld because church officials feel the complaints against them lacked credibility. The study shows a slow climb in the percentage of accused priests in the archdiocese from the 1960s through the '70s. The increase was especially notable among diocesan priests as opposed to those in religious orders. Overall, the analysis shows that the percentage of priests in Southern California who were accused of molesting children largely tracked estimates that 4% to 5% of priests nationwide are accused. But diocesan priests in the archdiocese were accused at a rate of at least 7% across the decades, which is higher than estimates of the national average for diocesan priests. Religious-order priests such as Franciscans, who answer to other superiors and move in and out of Los Angeles parishes, were accused at less than half the rate of the diocesan clerics. Religious-order priests usually do not work in parishes or elementary schools where they would have charge of young children, Hennigan said. Starting in the 1950s, the percentage of diocesan priests who eventually would be accused of wrongdoing climbed steadily from about 6% to a high of 11.5% in 1983. From there, the percentage of accused priests gradually fell, remaining above 5% until 2002, when Mahony implemented the "zero-tolerance" policy and removed seven accused priests from ministry. Hennigan said the church found the same sharp rise in alleged abuse, peaking in 1979. "The curve is quite a sharp one; it goes up sharply and falls off sharply," he said. "We have talked about it internally. I don't understand why that peak." An independent review board studying the sex-abuse crisis nationwide found that a "laxity" in seminary admissions, the sexual revolution and radical changes within the church sent the number of accused priests soaring around 1980. Hennigan attributed the drop-off starting in the 1980s to improved screening of priest candidates, the introduction of sexuality curriculum in seminaries, and recruitment of older candidates with life experience. A few churches had unusual concentrations of alleged abusers, the study showed. Seventeen parishes had been assigned five or more accused priests over the 55-year span of the study. Several parishes had two or three at the same time. Critics such as former Benedictine monk A.W. Richard Sipe say the church nationwide tried to keep the scandal quiet by shuffling priests from parish to parish instead of reporting them to police or firing them. "There were thousands of kids who were put at risk because these were not one-time offenders or offenders in only one parish, but they were moved from parish to parish," he said. "As a parent, it makes me furious," said Margaret Schettler, who works at Our Lady of Grace Catholic Church in Encino and has counseled parishioners and abuse victims. "It could have been my children." Today, most of the accused priests are dead or retired, or have left the area, and newer parishioners are unaware that their churches were touched by the scandal. Lindy Lizenbery became a parishioner at St. Genevieve's in Panorama City in 1978 and now works in the church office. Eight priests who worked at the parish at one time have been accused. Lizenbery said she doubts all eight are guilty. "There were those that I thought, 'Probably,' and a couple that I said, 'No way,' " she said. "If one of these guys did something to a child, that's one too many." But most parishioners contacted by The Times said they did not want to talk about clergy sexual abuse. "Everybody has to live there," said an usher at Holy Family Catholic Church in Glendale, explaining why people did not want to talk. "It has to do with simple, common parishioners who don't want to engage their fellow parishioners in something as sensitive as this." But because of the dearth of information, many Los Angeles-area Catholics are unaware their own parishes were affected by the scandal. "Some people are afraid of the issue," Schettler said. "Some wish survivors would just get over it." Times staff writer William Lobdell contributed to this report. * Priest abuse accusations in the Los Angeles Archdiocese The 228 priests who have been accused of child molestation were assigned to three out of four parishes in the Los Angeles Archdiocese at some point from 1950 to 2003. Though they were accused of molestation at about 100 parishes, the priests lived or worked in the 221 parishes mapped below. The parishes are in Los Angeles, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties.

Diocesan priests -- those employed by the archdiocese -- account for almost half of those accused. Religious-order priests such as Franciscans accounted for more than a third. Diocese 47.5%

Sources: Los Angeles Archdiocese, lawsuits, the official Catholic Directory. Data analysis by Doug Smith and Sandra Poindexter |

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.