Betrayed and Scarred As a Child by a Parish Priest, a Sexual Abuse Victim Looks Back on His Life

By Meg Kissinger

Journal Sentinel Online

April 13, 2002

http://www2.jsonline.com:80/news/metro/apr02/35139.asp

Even now, 27 years later, Scot Edgerton flinches when he thinks of that morning in the sacristy at St. Aloysius Catholic Church in West Allis, and how the priest grabbed him from behind, thrusting his hands down the boy's pants.

"I could see people in the church," he said, tears filling his eyes. "I was screaming, 'Help me! Help!' But no one came to help."

Edgerton is still screaming, in a manner of speaking, and finally someone is listening.

|

| Scot Edgerton leaves morning Mass at Holy Assumption congregation near his home in West Allis. Despite a sexual assault by a priest at another church as a teenager, Scot's faith has remained strong. Before he was assaulted as an altar boy, Scot was considering the priesthood. Photo/Gary Porter |

|

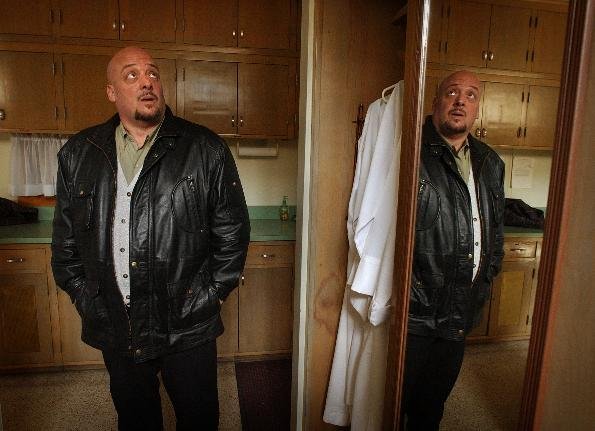

| "Not much has changed here," says Scot Edgerton, taking a deep breath as he revisits the sacristy at St. Aloysius Catholic Church in West Allis, where he says he was sexually assaulted by a priest 27 years ago. Photo/Gary Porter |

|

| Edgerton works in the building located below his home. He is converting the space into a hair salon and hopes to rent it out. Edgerton has run four other shops in the past and now works the third shift at a grocery store. Photo/Gary Porter |

|

| A political cartoon on a dresser mirror in Edgerton's home mirrors his frustration with the reaction of the Catholic Church to allegations of sexual abuse by priests. Photo/Gary Porter |

As the nation reels from allegations of sexual abuse by Catholic priests and the decades of coverup by church officials, Edgerton has chosen to tell what happened to him in an effort to find resolution for himself and the faith community he still loves.

"I'm a mess," said Edgerton, shaking his head. His eyes are red from crying. At 40, Edgerton stands 5 feet 11 inches tall and weighs 318 pounds. With his head shaved bald and his shiny, black leather jacket stretching across his broad shoulders, Edgerton looks more menacing than vulnerable.

"I know I should be over it," he whispered. "But I'm stuck."

Reading the recent news of allegations in Boston and elsewhere in the country has been a continual reminder of how he was attacked by a priest after serving a funeral Mass in 1975 and the months of psychological abuse that followed. Enough is enough, he said. This secret has festered for too long.

Edgerton decided it was time to make peace with the priest who assaulted him. So, he invited a reporter along as he set out to deliver a most surprising message.

"I'm not angry at him," Edgerton said a few weeks ago. "He's sick. He doesn't deserve me to be angry at him. It's taken a lot of years to get here. But I want to tell him he doesn't have that kind of power over me anymore."

He hoped that the priest would apologize. But, more than that, Edgerton craved the chance to tell the priest that he forgave him.

"I've got to let go," he said.

Outgoing, friendly priest

This is his story of that day, confirmed by his mother, documented in a letter that he wrote to Milwaukee Archbishop Rembert Weakland in 1980 and not disputed today by the archdiocese.

Edgerton was 13 years old, an eighth-grader, when his family moved to St. Aloysius in 1974. Having served as an altar boy at his former parish, he was eager to serve Mass at St. Al's. The boy was the only server on duty that day. Before the funeral began, the priest, Richard W. Nichols, approached Edgerton and told him the cassock he had selected didn't look right.

"He took me over to the closet and sort of dressed me, I guess you'd say," Edgerton recalled. "It was strange."

Nichols, an associate at St. Al's, had been ordained a priest in 1958 and served at a number of parishes, including St. Thomas Aquinas Church in Waterford and three churches in Milwaukee - St. Lawrence, SS Peter & Paul and St. Catherine. He had received his doctorate in psychology the year before at Marquette University.

"He was a real outgoing guy," Edgerton recalled. "Very friendly with all of us."

After the funeral had ended, Edgerton returned to the sacristy. He was hanging up the cassock when Nichols grabbed him from behind.

"I thought he wanted to wrestle with me," Edgerton said.

At first, Edgerton said, he played along. But the priest's grip was getting tighter and Edgerton remembered feeling as if he couldn't breathe.

From where he stood, Edgerton could see some of the mourners lingering in the back pews. Edgerton said he struggled to break free but Nichols managed to push his hands down the boy's pants and grab his penis.

"I can see funerals really excite you," Edgerton said the priest told him.

At that point, Edgerton spun around and broke loose, running from the church into the courtyard.

"I remember sort of roaming around aimlessly," said Edgerton. "There was a Rexall Drug Store across the street, and I went in and bought a candy bar."

His head felt as if it was spinning, he recalled, and he was panting for air.

"The next thing I knew, it was lunchtime," Edgerton said. "Hours passed that I had no idea what had happened."

Whatever the physical attack did to confuse him, the months of harassment that followed served to terrify him, Edgerton said.

"He was after me," Edgerton said.

For the next several months, Edgerton said, he did everything he could to stay away from the priest. When the two met in the hallways or in church, Nichols frequently commented on the boy's appearance.

Those pants look great on you, the priest would say. Or, "How's my shining star today?" Eventually, the remarks grew more taunting, Edgerton recalled.

He remembered the priest saying, "Those pants are getting a little tight. Careful. No one likes a fat boy."

"I remember thinking, 'OK. He doesn't like fat boys. So, that's what I'll become,' " Edgerton said.

"I built a nice little wall around myself."

Feeling guilty

By his senior year at Pius XI High School, Edgerton weighed more than 400 pounds.

Looking back now, Edgerton knows he did nothing wrong. But at the time, he said, he felt so guilty about what had happened.

"I blamed myself for being there," he said. "I wondered if I hadn't done something to encourage him."

As if to fulfill his own prophecy, Edgerton began to act out, sneaking out of the house at night, going to bars, acting recklessly, making decisions he now regrets.

He argued often with his parents, who chalked up the boy's behavior to his confusion about growing up.

It was during this time, Edgerton now knows, that Nichols asked for and was granted a break from parish assignments so that he could pursue his career in child psychology. He set up an office on S. 108th St., just a few miles from the church.

Despite his secret wild side, Edgerton remained active in parish activities, especially a folk choir that he had helped to organize. But he was growing more restless and confused. When it came time for him to decide what to do with himself after high school, Edgerton broke down and told his parents everything.

"We were shocked," recalled his mother, Shirleyan Jacobsen. "You're supposed to be able to trust a priest."

Another boy in Edgerton's class had told his parents of a similar incident involving Nichols and, despite worries that they would be ostracized for causing a fuss, the four parents made an appointment to talk with the pastor.

"He told us to have Scot write a letter to the archbishop and explain what had happened," Jacobsen said. He did and, in a hand-written reply, Weakland asked Edgerton if he could forgive the priest.

"I decided not to go on to college," Edgerton said. "I see now that I was scared to move again. The last time I had moved, it was to join St. Aloysius, and you can see how well that turned out."

Through the pastor, Edgerton was offered counseling, paid for by the archdiocese. Edgerton remembers attending five or six sessions with a therapist named Leo Graham. Graham, who died in 1999, counseled a number of abuse victims in the archdiocese. He surrendered his license in 1987 after accusations of sexual misconduct with a patient.

"That helped," Edgerton said of meeting with Graham. But events over the next several years would prove agonizing to Edgerton, who worried whether he had done enough to stop Nichols or whether the priest would abuse other boys.

As it turned out, his fears were warranted.

Not reported to licensing board

What Edgerton has learned over the past few weeks has shocked, saddened and angered him.

Records show that even while paying for counseling for Edgerton in the early 1980s, archdiocesan officials continued to allow Nichols to perform priestly functions. Most disturbing to Edgerton now is the fact that the priest was working as a child psychologist at a clinic in West Allis at the time, and that, even though the archdiocese knew of this allegation, there is no record that anyone from the office reported Nichols to the police or to the state's licensing and regulations board that monitors the actions of psychologists.

"What did they think was going to go on in his office?" asked Edgerton. "How could they take that risk?"

In an interview Friday, Weakland said Nichols was removed from many priestly duties in 1981 after Edgerton's letter, though he was permitted to say Mass for the School Sisters of Notre Dame at their convent in Elm Grove. But the archbishop could not recall whether the archdiocese had notified the state licensing board about the complaints against Nichols after they surfaced in 1980.

"I was curious why the board of psychologists allowed him to continue to practice," Weakland said.

Jerry Topczewski, archdiocesan communications director, said archdiocesan practice in 1980 was not to report the abuse to authorities but to encourage the victims to do so. But Jacobsen, Edgerton's mother, said that when she and her husband met with the pastor at St. Aloysius to report their son's claims, the pastor urged them not to take the matter any further. That priest has since died.

"They wanted this taken care of as quietly as possible," Jacobsen said.

Indeed, three years after Edgerton came forward, a boy reported Nichols to the state licensing board, saying he had engaged in oral sex with Nichols while a patient in the West Allis counseling office in November 1978. In a deposition signed in September 1984, Nichols admitted that the oral sex had taken place with the boy in his office. Six months after that, in February 1985, an article in The Milwaukee Journal revealed the allegation and the priest's admission. Four days later, a spokesman for the archdiocese announced that it was launching an investigation of Nichols.

The following month, Nichols surrendered his license and the state licensing board dropped its disciplinary actions against the priest. Nichols left Milwaukee, moving to a house in Neshkoro, a town in Marquette County.

Topczewski said Nichols was barred from performing any priestly duties after the state began its investigation, although Nichols still was not formally removed from the priesthood. The archdiocese notified the diocese of Madison, which oversees churches in the Neshkoro area, of Nichols' limited status, Topczewski said.

Nichols was diagnosed with cancer and moved into a condominium that he and his mother bought in New Berlin in 1996. He died of a heart attack in July of that year. His funeral Mass, celebrated by Bishop Richard Sklba, was held at the Holy Family Chapel at Notre Dame of Elm Grove where Nichols had served as chaplain in the years after Edgerton's complaint and before he moved to Neshkoro.

Edgerton cried when he learned last week that Nichols had died at age 63.

"I heard rumors, but I didn't think it was true," he said.

There was so much he wanted to say to Nichols, and so many questions he wanted to ask him.

"I wonder if he ever came to terms with what he had done," Edgerton said.

Nichols' sister, Joyce Portz of Sun City, Ariz., said her brother was very troubled. He had tried many times to be granted permission to say Mass again, only to be denied by Archbishop Weakland.

"At first, we thought the things they were saying about him weren't true, but now," Portz said as her voice trailed off. "Well, I guess we'll just let sleeping dogs lie. No, actually, we'll let dead dogs lie."

Portz said she was heartened to hear that Edgerton does not harbor ill feelings toward her brother. She is angry, she says, at the manner in which the allegations were treated.

"They hushed everything up," she said of church officials. Ultimately, that did not serve her brother well, either, Portz said.

"We've been through a lot."

Return to the sacristy

Edgerton's search for resolution led him to the Cousins Center in St. Francis to the same office where he first complained about Nichols 23 years ago - and, ultimately, to the sacristy in West Allis where the attack happened.

Edgerton met Monday with Barbara Reinke, director for Project Benjamin, the archdiocese's program for those who have been sexually abused by priests. He told her how he's bounced around over the years from one "crappy job" to another, how he works third shift now as a grocery store clerk, how his anger keeps interfering with his relationships.

"I'm so sorry this happened to you, Scot," Reinke told him. "This much I can promise you. We will get you some help."

The archdiocese will pay for counseling from a therapist of his choosing, she said.

"Keep yourself open to the idea that this might take some time," she told him.

"I think I'm finally going to get some peace," he said, wiping tears from his cheeks.

That same day, Bishop Sklba returned his call and said that he, too, was sorry Edgerton had been hurt.

Edgerton had heard from friends that Father Thomas Suriano, pastor at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church at S. 58th St. and Forest Home Ave., had delivered an emotional homily last Sunday, offering an apology to all the victims of sexual abuse on behalf of the Catholic Church and calling on the leadership to end the cycle of coverups.

Edgerton called the priest that night and asked if they could get together.

During their meeting, Suriano said something that Edgerton had waited more than a dozen years to hear.

"I told him that I wanted to tell Father Nichols that I had forgiven him and he told me, 'Scot, I accept your forgiveness.' Wow. That felt very good," Edgerton said. "It's amazing how powerful it is to hear those words."

Weakland said last week he was glad that Edgerton has come forward to tell his story.

"I think it is an important part of his ability to heal," the archbishop said. Asked what he would say to Edgerton, Weakland said, "I would apologize very deeply to him and tell him that I hope that he gets some very good counseling."

Still, there was one last chore to be done.

Edgerton marched up the steps to St. Aloysius as the early spring sun made its way through the afternoon clouds. The door was locked. He waved to the janitor who was sweeping the hallway.

"Mind if we come in and look around a bit?" Edgerton asked.

His heels clicked as he walked down the aisle to the sacristy on the side of the altar where the sprays of purple and yellow flowers announced the joy of Easter resurrection.

He inched toward the closet where the cassocks hang.

The cupboards were neatly marked. Chalices. Vestments. Communion wine. Hosts. They are the symbols, so rich, of Edgerton's faith.

"People always ask me how I can still be Catholic," he said. "I don't know. My relationship with God is one thing. What happens with another human being is something else."

He stood there for a minute and sighed.

"This is where it happened," he said. "Right here. See how you can see out into the church?"

Edgerton looked around for a while, his eyebrows twisting toward one another. Then he stood up straight, took a deep breath and chuckled.

"Want to know something funny?" he said. "It's a lot smaller than I remember."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.