By Stephen Kurkjian and Sacha Pfeiffer

Boston Globe

August 15, 2002.

Three days after Bernard F. Law became archbishop of Boston in March 1984, an anguished parishioner from Franklin wrote Law a detailed letter alleging that a parish priest had twice sexually assaulted his wife and that the parish's pastor and the local auxiliary bishop then treated the couple with hostility when they complained.

In the letter, Gregory B. Nash implored Law to open his "shepherd's heart" to meet with him and his wife and help them deal with the alleged assaults by the Rev. Anthony J. Rebeiro.

But Law did neither.

In a terse letter of response on April 3, 1984, labeled "Confidential," Law said only this about the sexual allegations: "After some consultation, I find that this matter is something that is personal to Father Rebeiro and must be considered such."

|

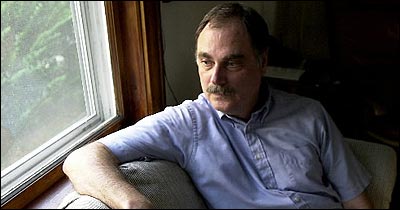

| Gregory B. Nash's request for help from Cardinal Bernard Law was dismissed. Photo by Essdras M Suarez |

Last Saturday, Rebeiro, who is now 71, was suspended from his chaplain's post at the Quigley Memorial Hospital and Soldiers' Home in Chelsea, but not for the allegations Nash brought to Law's attention in 1984. Instead, his removal was prompted by new accusations that he had abused a child at St. Linus Church in Natick in the early 1970s.

In 1984, just before Nash wrote to Law, Rebeiro was transferred to St. Patrick's Church in Natick, and then to parishes in Woburn and Holbrook over the next four years before he began a 12-year stay at St. Anthony of Padua Church in Revere in 1989.

Rebeiro, in a telephone interview yesterday, said he never acted inappropriately with Nash's wife. He said the transfer came at his request after the archdiocese cleared him of the allegations. But he was unable to say who conducted the investigation or who informed him that the charges were found groundless.

Donna M. Morrissey, a spokeswoman for the archdiocese, said last night that she could not answer questions about the issue because it arose in Law's deposition on Tuesday, and Law's lawyers are bound by rules forbidding them to discuss what was said.

J. Owen Todd, Law's personal attorney, said the cardinal "does not have any present memory" of the complaint or his response to it. Todd also said that Law saw Nash's letter for the first time on Tuesday and would have to examine church records before offering a substantive comment.

Rebeiro was accused by Nash's wife of exposing himself and masturbating in front of her in a rectory office. She said he also tried to force himself on her during an unsolicited visit to her home.

In a deposition transcript made public Tuesday, Law admitted to other instances in which priests who had sexually molested children were not removed from contact with children. But the alleged assault at St. Mary's Church in Franklin opens another wound for the embattled archdiocese: charges that a priest sexually abused an adult woman - incidents that specialists say are common but often go unreported or are treated lightly because the church has often reflexively cast the victim as the instigator.

Nash's ex-wife - they divorced in 1993 - said she has long been dismayed by the church response to her allegations. "I was shocked to be approached like I was by Father Rebeiro," she said yesterday. "It was sickening and humiliating. But then to have his superiors treat us like we were the problem, not him ... I lost a lot of faith."

In Nash's letter, and in separate interviews this week, Nash and his former wife decried the abuse but reserved much of their anger for what they described as humiliating treatment at the hands of Rebeiro's pastor at St. Mary's, the Rev. Henry P. Boivin; and Auxiliary Bishop Daniel A. Hart, then head of the Brockton region, and since 1996 the bishop of the Norwich, Conn., diocese.

But even though the allegations involved potential felonies, Boivin turned them against Nash's wife, Nash said in his letter and in an interview this week, asking detailed questions about her past psychological and sexual history and telling Nash she bore some responsibility.

Boivin yesterday declined to discuss the issue. Hart, through a spokeswoman, also refused to answer questions.

The passage of 18 years has not dulled the frustration and outrage that Nash feels toward Rebeiro and Law about the episode. "I thought they would get to the bottom of the problem and offer my wife the care and counseling she needed," he said in an interview Tuesday. "Instead, just the opposite happened. They treated us as outcasts and protected him."

In a day-long deposition on Tuesday, Roderick MacLeish Jr., a Boston lawyer who along with his partner, Jeffrey A. Newman, has been retained by Gregory Nash, questioned Law about his handling of Nash's 1984 complaint. Paula Ford, the mother of an alleged victim of the Rev. Paul R. Shanley, attended Tuesday's deposition and said in an interview yesterday that Law - despite his signature on the letter - testified that he did not recall the complaint. However, Ford said that Law testified that he believed there was a "qualitative difference" between clergy sexual abuse toward a minor and toward a female. Law's lawyers cut off the questioning before Law could explain the difference, Ford said.

MacLeish called Law's letter of reply to Nash as "one of the most striking and insensitive documents that I have ever seen."

It was also during Law's first months in Boston that he made his decision to reassign the Rev. John J. Geoghan to a Weston parish even though he had been informed that Geoghan had admitted to repeatedly molesting seven children in one extended family.

After Rebeiro's suspension was made public, Nash first contacted the Globe and then retained MacLeish, although he says his intention is not to seek a monetary settlement but to ensure that Rebeiro is permanently removed from ministry.

In recounting what happened in 1983, Nash and his former wife said no one at the archdiocese ever asked them to provide details of the two incidents. Instead, they said, they sat through demeaning meetings with both Boivin and Hart.

In his March 1984 letter, Nash expressed his frustration to Law. "Our experience with the archdiocese has been deeply troubling. It has reminded us of one of those large corporate entities which silently closes ranks to protect one of its own. We would like to think we are one of the church's own, that we should be protected," Nash wrote, adding: "It is also uncomfortably reminiscent of the rape victims who traditionally have been raked over the coals, who have been victimized a second time by being made to feel responsible, who have been ostracized by their own."

In that letter, and in interviews this week, Nash and his former wife, whose name is being withheld by the Globe because she is an alleged victim of sexual assault, recounted the two 1983 incidents.

The first took place in May 1983 in the rectory of St. Mary's Church in Franklin after an evening group prayer meeting. After the meeting, Mrs. Nash, as directed by Rebeiro, locked up the church building and brought the key back to him at the rectory.

Rebeiro, she said, met her in a first-floor parlor and after closing the door to the room and blocking her way out, told her that she was a "bad girl" for having come to the rectory and that he needed to spank her.

Mrs. Nash recalls mumbling some protest but within moments, Rebeiro had dropped his pants, exposed himself, and masturbated.

"I left horrified and bewildered," she recalled. According to prosecutors and defense lawyers, if a person exposes himself in public or makes a sexual gesture with their genitals to another person, they can be charged with open and gross lewdness, which is considered a sexual abuse felony.

While she does not know why Rebeiro singled her out, Nash's former wife said it may be related to her having told Rebeiro months before that she had once been raped. "I remember him telling me that in cases like that he always thought the best thing was to relax and enjoy it, which I thought a pretty awful comment," she said.

Embarrassed by the rectory episode, she decided not to inform her husband. Instead, she told a priest friend. His advice: Avoid Rebeiro. Forgive him for the alleged incident. But do not report him to his superiors.

Several months later, she said, she informed her husband of the episode and together they decided to keep their distance from Rebeiro. "We were very involved in the church with our children," Nash said. "We wanted to avoid disrupting that relationship we had with the church."

But that hope evaporated shortly after Christmas 1983. Mrs. Nash was alone in her house while her husband was in Florida when Rebeiro appeared at the house. With the Nash children watching television in another room, Mrs. Nash said, Rebeiro tried to caress her. When she pushed him away, he asked her to unbutton her blouse so she would feel more at ease.

"He kept coming after me, pawing me, trying to touch me, and I kept pushing him away. It was very uncomfortable but I didn't want to scream out because it would have alarmed the children," she said yesterday. Finally convinced that he was unwanted, Rebeiro got up to leave. But after a few steps he turned back, grabbed Mrs. Nash, and kissed her open-mouthed on the lips until she shoved him away, she said.

When she told her husband, they decided to report Rebeiro to Boivin, the pastor. Meeting with Boivin on New Year's Day, Nash outlined the specifics of what his wife had told him. Boivin's response, as detailed in Nash's later letter to Law, was to question Nash about his wife's sexual and psychological history. "He implied that if any of what I said was true, she must bear some of the responsibility," Nash wrote.

In a separate meeting the next day with Mrs. Nash, Boivin subjected her "to the same line of questioning and innuendo," Nash wrote. However, following their meetings, Boivin outlined a plan under which he would question Rebeiro about the matter and order him to stay away from the Nash family.

Weeks later, the Nashes, having decided that Rebeiro should be removed as a priest, sought out Bishop Hart.

After listening to them, Hart told the Nashes that this was the first time he heard any complaints about Rebeiro, and as for their credibility, he told the Nashes: "I don't know you from Adam," according to Nash's letter to Law.

Although Hart made no promise to look into the matter or refer it to his superiors, the Nashes are convinced that he took their complaint seriously. Rebeiro was transferred to Natick.

But the Nashes, by their account, also felt like outcasts in their parish. Boivin, they said, told them they were no longer welcome at St. Mary's and should find another parish.

And even though Boivin gave them $800 to help pay for Mrs. Nash's psychotherapy, Boivin told them that they were taking money that would have bought food for the parish's needy, Gregory Nash recalled.

Incidents of priests engaging in unwanted sexual encounters with adult women are far more common than reported incidents suggest, according to specialists in clergy sex abuse.

A. W. Richard Sipe, a therapist and former priest who has written several books on the subject, said Law's handling of the Rebeiro case underscores how devalued women are in the church. From his own studies, Sipe said, he has found that complaints from women are routinely dismissed, most often after church officials reflexively conclude that it is the victim who seduced the priest and led him into sin.

Law's brief response to Nash, Sipe said, "is eloquent for its lack of concern and for its signal that women do not count in the church."

Barbara Blaine, president of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, who was sexually molested by a priest when she was a minor, said church officials most often blame women when women accuse priests of molesting them.

"The church sees the act as a weakness by the priest," she said. "They do not see it as a crime, but as a small violation of their vow of celibacy."

And because society in general and the church in particular have often reacted dismissively or skeptically when women allege sexual abuse, it is inevitable that many female abuse victims are reluctant or unwilling to go public with their experiences, according to Boston lawyer Wendy Murphy, a former prosecutor who frequently represents sexual abuse victims.

"Before we even think about believing them, we wonder about their mental health background and we wonder about their sexual history," Murphy said.

Moreover, she added, the challenges faced by female victims in the secular world are magnified in a church setting where, she said, the hierarchy is much more dismissive of women.

Michael Rezendes, Thomas Farragher, and Walter V. Robinson of the Globe Staff contributed to this report.

Stephen Kurkjian can be reached at kurkjian@globe.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.