By Peter Rugg

The Pitch

October 9, 2008

http://www.pitch.com/2008-10-09/news/the-ghosts-of-st-elizabeth-s/

The cold face of the St. Elizabeth rectory gives no indication of comfort within. Inside, its walls are painted in bright crimsons and calming blues, adorned with pictures of the Savior. Some priests ended their lifework here, meeting their Maker in the bedroom where windows overlook the courtyard behind the church. Built in 1948, the rectory was designed to house four priests and a live-in housekeeper. Today, the priest lives alone.

Robert Bates has not been inside the building for more than 20 years, though it often crosses his thoughts.

Bates did not attend the church. He and his mother were members of St. Vincent de Paul at 31st Street and Flora, where his mother did clerical work for the church. His father left when he was 2, and his nearest male relative was a half brother, from his mother's first marriage, who was already old enough to have fathered a boy the same age as Bates.

In 1980, a young man named Earl Johnson came to St. Vincent de Paul to finish his education and preparation for the priesthood. He was a tall, burly man, with a rough beard and rosy cheeks. While he worked at St. Vincent de Paul, Johnson lived in the St. Elizabeth rectory.

|

| The Ghosts of St. Elizabeth: For Kansas City's Catholic sex-abuse victims, this was a parish of pain. Photo by Peter Rugg |

He took an interest in Bates, then 12, and the two became friends. Johnson tried to provide everything Bates needed. He bought the boy so many meals at Kentucky Fried Chicken that Bates still avoids the restaurant.

Bates and his friends — three neighborhood brothers known as good athletes — became regular guests at the rectory on weekend nights. There were few rules. They would stay in the rectory's entertainment room, eating popcorn or watching movies all night. "We pretty much ran the block," Bates remembers.

The priests at St. Elizabeth were heavy drinkers, and they encouraged the boys to share their habits, Bates says. He could always ask the priest for a bottle. Once, when Bates and his friends were drinking in a nearby park and saw police walking toward them, they ran for shelter at the rectory, leaving the beer behind.

If gifts didn't convey his affection for Bates, Johnson would grip him and pull him close, whispering in his ear that he was a good boy, that Jesus was proud of him and loved him.

|

| The Ghosts of St. Elizabeth: For Kansas City's Catholic sex-abuse victims, this was a parish of pain. Photo by Peter Rugg |

"I'd never been around men before," Bates says. "I didn't know how to take any of it. Then he'd be bear-hugging me when we were alone and talking to me and bringing God into it. I didn't know if that's how men acted."

Only once did Bates question Johnson's friendship. On one Saturday visit, he and a friend had agreed to help clean the rectory. Johnson greeted them and insisted that they change so they wouldn't dirty their good clothes. Johnson provided them with T-shirts and shorts two sizes too small and gave each a feather duster. Then he set them to work reaching up to dust the light fixtures. As Bates dusted the dining-room lights, he looked down at a gathering of priests eating dinner together. They were giggling, whispering and pointing at him. Bates dismissed it as a social mannerism of adult males that he didn't yet understand.

|

| Bishop Robert Finn of the Catholic Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph reportedly listened uncomfortably to Robert Bates’ story. Photo by Peter Rugg |

Two weekends after cleaning the rectory, Johnson called Bates. He invited him to the rectory and promised him that the athlete brothers would be there. It was late summer.

Johnson picked him up that night and drove him to the rectory. Other priests were there, some whose names Bates didn't know. The brothers weren't there, but Johnson promised they'd be along.

"Oh well, I guess that's just more fun for us then, right?" Johnson told him later when the brothers didn't show up.

|

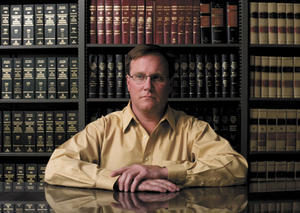

| Steve Schleicher says he offered to buy St. Elizabeth’s rectory so he could tear it down. |

Johnson suggested that they camp out in the basement. Bates followed him down the stairs, then into a room where Johnson laid out a sleeping bag.

Bates lay in the dark trying to sleep, feeling Johnson shift against his body. He pretended to be asleep, then he felt the man's hands.

God just save me, Bates thought. If you save me from this please, God, I'll do anything. Please, God Jesus.

A door opened, and light cut into the room. Standing there was a lean, balding priest. Bates didn't know who the man was.

Thank God. Thank God. He sent you here to save me ...

The priest looked at the bundle on the floor. "I'm sorry," he said. Then he shut the door and left them alone.

Later, Bates says, Johnson cried and asked for forgiveness. He

begged him not to tell anyone and promised to buy him things. Bates

just lay there. For another two summers, they repeated the scene. Bates

told no one.

In August, Bates and 46 other victims of sexual abuse were awarded $10 million from the Catholic Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph. The settlement brought an end to a case filed by attorney Rebecca Randles, who began representing victims in 2002, one year after reports from Boston spurred a Catholic sex-abuse scandal nationwide. Along with Johnson, the suit named 11 current and former priests. At least three of them lived at St. Elizabeth. Randles says approximately half of the cases involved the rectory.

Located at 75th Street and Main, St. Elizabeth is the spiritual home of more than 1,000 Kansas City families. The rectory's best-known former residents are Monsignor Thomas O'Brien and the Rev. Thomas Reardon, the men most frequently named in the lawsuits. Neither Randles nor the diocese could provide their contact information, and The Pitch was unable to locate them for this story.

But O'Brien and Reardon are now notorious for behavior alleged in court documents. From the 1970s to the mid-'80s, for example, they threw parties at Lake Viking, an hour north of Kansas City near Gallatin, where they plied young boys with alcohol and forced them into such sexual acts as masturbation, oral sex and sodomy.

As part of the settlement, the diocese made nineteen non-monetary commitments — it would pay for counseling, for example, and wouldn't provide job references for priests named in the suits. Randles touted it as the most far-reaching set of promises yet negotiated in this type of case in the United States. In the first of the 19 non-monetary agreements, the diocese pledged the following: "Through a press statement to the secular media and through publication in The Catholic Key, the Diocese will continue to publicly acknowledge the wrongfulness of sexual abuse by the perpetrators, and will acknowledge that its own response to reports of sexual abuse has, in the past, been wrong."

The victims didn't get everything they had asked for, though.

Among the terms that the diocese refused was a request for church officials to turn over ownership of the church rectory. These days, the pews of St. Elizabeth swell with parishioners, many of whom were educated in the school next door or send their children there today. Randles says many of her plaintiffs wanted to see the building torn down.

Today, the rectory is home to the Rev. Terry Bruce. At 62, he has the fit frame of an athlete and receding white hair. Having spent 41 years in the Catholic Church, Bruce came into the parish, in 2005, knowing its history.

"There's always been tension here, and I've never really known what the right way is to deal with it," Bruce says. "It's ground zero."

The Sunday after the settlement was announced, Bruce stood at the altar. He had decided to talk about it. He waited until the day's visiting priest was finished with his sermon and the Mass was almost over before speaking.

He wasn't sure what the reaction would be.

"This ominous cloud that has hung over our heads has cost us far more in intangible ways than any 10 million dollars," he told his congregation. "Of course, the boys are the first victims. But then there are their parents, spouses, siblings, children, classmates. All priests come under a jaundiced eye. There is a loss of faith, confidence and credibility on the part of all of us.

"A sure way to feed the embers and keep them alive and driving them deeper is by denying that anything ever happened or by accusing the accuser and blaming the victims," he continued. "That justly infuriates all involved. This is not over."

After the Mass, there was no visible reaction. People filed out of the pews as they did on any Sunday. On the way out, one whispered about the abuse: "I just couldn't believe a Catholic could do that."

While Bruce encourages his congregation to continue talking about what had happened, viewing the discussion as a necessary salve, others think the church hierarchy is as committed to silence as ever, no matter what apologies it offers.

"All this apology stuff, whatever [Bishop Robert] Finn says, that's bullshit," says Bates, who was last inside St. Elizabeth in 1982. "They fought every one of us in court as long as they could. At the end, they weren't even arguing it happened — just lawyers asking about dates and times trying to find a way to beat the statute of limitations. The only thing they're sorry about is having to pay. Nothing is over."

The Pitch attempted to speak with Finn for this story. Diocese spokeswoman Rebecca Summer refused to allow comment from any church administrator. "This is a time of healing," she said. "There is a very real need for healing. So to continue to further the discussion beyond what we've already [publicly] furnished is not respectful of everyone involved."

By 1993, Bates was a police officer. He had gone through periods of depression and drug use. He wanted to help people but when he saw another officer do anything that hinted at abuse of power, he backed the officer into a corner. His superiors told him that he was too aggressive.

That summer, he got a call about a disturbance at a business at 35th Street and Prospect. It was a small bar with an orange and yellow awning over the front door and words painted over the windows. Bates parked at the scene and waited for backup.

By the time they went inside, the men who had started the trouble had already left. Bates was taking a report from the bartender when he saw Earl Johnson leaning against the wall, looking at him. He looked the same as he had at St. Elizabeth.

Bates says Johnson approached him like an old friend, asking how he had been. He says Johnson mentioned that he had left the priesthood and was teaching elementary school.

Bates' mind raced as he remembered the nights in the rectory. This motherfucker is talking to me like everything is everything? Take out the service revolver. Aim it at his chest. Empty it. Blood everywhere, watch him fall down and die.

Suddenly, Bates noticed that his partner was pulling him away. He hadn't realized that he was poking his finger into Johnson's chest and screaming obscenities.

"I told my partner he'd done something to my family a long time ago," Bates says. "She was a female, and I didn't know her that well, and I'm not a person who's just going to open up like that. I cried for days after that happened."

Later, Bates berated himself for letting an opportunity go. He knew that he was now an adult and in a position of authority, and he thought that he could have done something.

Not long after the encounter, Bates left the police department and became a firefighter.

"The fire department was great because if I show up, I'm coming to save your ass," Bates says. "I'm not taking you to jail. I'm not dealing with disturbances. I'm coming to save you. Everyone was happy to see me. I loved being a fireman. But I suppressed this shit for 20 years, and eventually it all got fucked up."

He had flashbacks and nightmares. Already a drug user, he used more to cope with the memories. He stayed up all night during his shifts at the fire station while everyone else rested.

Both he and his mother had stopped going to church years earlier. She was sick, and he decided that she should know what had happened to him.

"Over the years, she'd started to figure the church was bullshit, so I thought it would be OK to tell her," Bates says. "She was just broken when I told her. I think she felt responsible because she trusted him. It might have even killed her, for all I know." She died of a heart attack later that year, and Bates felt even guiltier.

The first time he tried to commit suicide, he took all of his mother's heart medicine. Someone found him and took him to the hospital to get his stomach pumped. "The pain's so bad from getting that done, you wish you had died," he says.

Sometimes he showed up for a shift at the firehouse, but just as often he didn't. Everyone knew he was using. His erratic behavior cost him his job in 2001. He left with the $20,000 left in his retirement fund. It was gone in three months.

At his worst, Bates would disappear for a week. His wife would find his car parked in front of what she assumed was a crack house. She would have the car towed and leave Bates there. He tried to commit suicide again, this time using the gas hose from the back of his stove to try to poison himself. A neighbor smelled gas and called the utility company before Bates succeeded with his plan.

Bates never saw Johnson again.

x

Before Bruce ever took over at St. Elizabeth, he knew Reardon and O'Brien. Bruce had been a seminary student with Reardon and remembered him as an outgoing, driven student with a winning personality. Reardon was known for his ambition and boasted that he had become a bishop.

"He was very smart. They were both very smart and worked very hard for a lot of people," Bruce says. "But they had a flaw. Everyone has a flaw. Theirs were very costly."

Perhaps more shocking to Bruce than the sexual abuse itself was the way the church dealt with the allegations. At the age of 15, he had an encounter with another seminary student who made sexual advances. Bruce reported the student to the administrators. Bruce never knew what happened to him, but the assumption was always that he had been expelled. He supposed that priests would be treated equally if they did the same.

He has tried to address what happened but never found a method with which he was comfortable. One time, a former parishioner, abused as a child, called him to discuss a support group, but Bruce says the man never contacted him again. He considered a healing Mass and discussed it with some older parishioners who worked in the church offices, but Bruce says they assured him that no one would be interested. He thought about a ceremonial blessing of the rectory but again decided that no one would care.

"I want to do things, but it's always seemed like there's no market for it," Bruce says. "Of the parishioners who were involved, most have moved out.... It seems like we should talk about it sometime and take the guilt off the victims, but there's still that cloud over discussing it."

The stigma prevents Bruce from talking as much as anyone else. He has made no inquiries of the general congregation and has limited his talks with the victims. He says nothing because he's afraid of saying the wrong thing.

"It's hard to find victims unless they come to you," Bruce says. "I just don't know how to proceed. If I knew how to find people or what to say, I would, but I don't."

The closest Bruce came to an in-the-flesh conversation was when he met Steve Schleicher, an attorney who had been a student at St. Elizabeth School in the 1970s.

Schleicher can look at a picture of his seventh-grade class and point to a half-dozen black and white faces, picking out the boys unlucky enough to have attracted the priests' attentions. Schleicher says he was never abused but has always wanted to do something for the many who were. His father, Charlie, was a member of St. Elizabeth for 45 years, and the two had conversations about the many children who had been molested in the rectory. Schleicher then started to think about tearing it down.

Schleicher had met Bruce a few times but didn't talk much with him until after Schleicher's father became ill and the priest paid a visit. In 2006, Schleicher talked with Bruce about doing a healing Mass for the victims. He says he got a letter from Bruce saying it was the right thing to do, but it never happened. Soon after, he went to diocese Vicar-General Robert Murphy with an offer to buy the building. He sat across the desk from him and took out his checkbook. Murphy turned him down.

Schleicher says he knew the offer would be turned down but had hoped for some serious consideration. "To me, this is a clear question of right and wrong, and about what lasting symbol you're going to see there."

He never went into the rectory until his father's funeral later that year.

Bruce says he doesn't see the purpose in Schleicher's offer.

Turning the land into a memorial park, he says, wouldn't heal anything. "If it did, fine. But I don't think anyone is benefited by it. Forgiveness is the only thing possible, and that's their choice for their own sake, to move forward."

Chris Nunilo wants the litigation to mark the last time he ever has to talk about what happened to him at St. Elizabeth. At 46, he doesn't go to church. He doesn't think the diocese cares about what happened to him, and he doesn't care what happens to St. Elizabeth. Like Bates, he filed his suit anonymously; unlike Bates, he asked that he be identified by a pseudonym in this story.

Nunilo was a classmate of Schleicher's in the mid-'70s. He began attending St. Elizabeth when he was 12. His family had moved from Des Moines, Iowa, to Kansas City when he was in kindergarten, and by the time he was ready for sixth grade, St. Elizabeth was considered one of the best parochial schools in the city. He worked at the rectory, answering phones and filling O'Brien's office refrigerator with soda. On Sundays, he was an altar boy.

His story is so common among the litigants. On weekends, O'Brien invited him to Lake Viking, gave him alcohol, and showed him and his classmates pornography. O'Brien masturbated in front of him and tried to cajole him into sex. Once, O'Brien promised him that he could talk a female parishioner into giving him a blow job, if he wanted it.

"It was an open secret to everyone," Nunilo says. "You'd call the rectory 'the parlor.' Monsignor was 'Mon Beat Yours.'... They'd just try to talk you into things, like get with the program, you know?"

He worked at the rectory for about a year and a half, and his parents encouraged him to continue. Aside from the sexualized environment, Nunilo says there were perks to being there.

"If I got into trouble at school, I could just skip out and go serve Mass. You could get away with a lot."

He tried to tell his mother about O'Brien early on.

"I think Monsignor O'Brien might be gay," he said. "He's doing things that make me feel uncomfortable."

"Honey," she answered, "you must have misunderstood."

Nunilo's family moved. He left St. Elizabeth School when he was in eighth grade and he stopped being an altar boy. He didn't speak again of what had happened until 2001, when his mother died and O'Brien officiated at the funeral Mass. It was the same year that he got his license to practice as a therapist specializing in victims of post-traumatic stress and sexual abuse.

"My younger brother was very upset, and I asked him, 'What's wrong?' He told me that mom knew now." Nunilo says O'Brien had done more to his younger brother than to him. His brother, who still believed in God, thought his mother would know everything now that she was gone, even though he had never told her.

Less than a year after they heard about the abuse cases in Boston, they found Randles, who was already taking abuse cases.

Compared with his classmates, Nunilo supposes that his life has been charmed. One boy with whom he went to school committed suicide. Many have had drug problems. At worst, Nunilo has had a series of failed relationships and says he has a hard time staying with someone.

"I've never been married. I've had my moments of substance abuse but nothing too bad. I fought my way back," he says. "As for the rectory, you know, it's a building. Tearing it down is Steve's deal. But some type of acknowledgment would be nice."

The week after the settlement, Bates was called in to tell his story again. This time, a priest would be there to hear it.

The flashbacks started again almost immediately after the announcement. That Monday, his wife arrived home to find their spare-change jar empty, and a suitcase was missing. She thought he had gone to a crack house and wondered how long it would take him to kill himself with his share of the settlement.

Bates says he wasn't staying with drug dealers, but he won't elaborate. "I was around," is all he'll say. "I was everywhere. I just couldn't be around anyone. That was a bad week, and I was used to running." By Thursday, his wife considered filing a missing-persons report.

He had, however, stayed in touch with his attorneys. On the day that Bates was scheduled to speak, he arrived at the attorneys' offices early. They took him into a conference room. Across from him sat Bishop Finn.

"It was a trip because when you're actually with him, you can see what's real and what isn't real," Bates says. "I think he really thought he was putting on a good show of remorse. It was a pitiful spectacle."

Bates started his story. Finn's head was bowed. Bates says the bishop kept his gaze on the floor.

"It's like he was really sick of hearing about this. He's shifting back and forth. It's like it's physically painful for him to be there."

As he watched Finn, Bates started to enjoy telling the story. The few times he'd told it had been wrenching ordeals. This time, he felt as if it was finally making the right person uncomfortable.

"I ran out of stuff to say and I didn't want to let him go. I didn't want this to be over for him," Bates says.

At last, Bates exhausted every word he could find. Finn wiped one dry eye with a handkerchief. The two men stood, and Finn offered his hand and his apology. Bates took the hand and looked Finn in the eyes. "I wanted him to know I wasn't beaten. I don't know if he got that, but that's what I wanted to get across to him in my eyes. I wanted him to know what they took. It was maybe the first time I'd ever really confronted them."

Bates returned to his family that Friday. He's in therapy now, hoping to finally leave his shameful secret behind him.

One night last month, at a party with his neighbors, everyone was going around the room and sharing the worst things that had ever happened to them. Bates told the story.

"I want people to know what they did to me," he says. "What else can they do to me now? Nothing."

As for the rectory? "They ought to burn that son of a bitch down."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.