An Unbearable Secret

By Richard Baker and Nick McKenzie

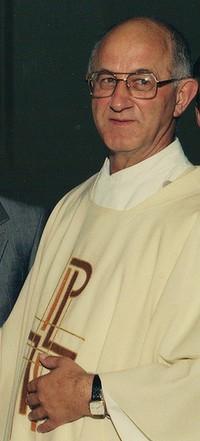

As a child and young man, Tony Hersbach was regularly sexually abused by a Catholic priest. He told no one for more than 20 years, and when he finally revealed all to the church hierarchy, it did nothing. By Richard Baker and Nick McKenzie. TONY Hersbach was 42 when he told his wife that the man who married them and played grandfather to their children had regularly molested him during his youth. Lu Hersbach's reaction to this bombshell was disbelief. The priest whom her husband had accused of despicable acts had been a dominant influence in their lives ever since he married them as 19-year-old sweethearts. Over the next 24 years Father Victor Gabriel Rubeo would dine with them on Sunday nights, accompany them on holidays and attend their children's birthday parties. He opened their mail and entered their bedroom unannounced. "The man was so entrenched in our family that when I was told … [it was like] someone really close to you has died. You have this sense of disbelief and I guess I hung on to this sense of disbelief for as long as I could," Lu Hersbach says. In contrast to his wife's disbelief, Hersbach felt immense shame for having exposed their four children to a man he knew to be a paedophile. "It staggers me now even to think that I allowed Rubeo to stay in my life. I know he had control over me but I still feel a lot of guilt and shame that I didn't protect my children," Hersbach, 59, says. Rubeo had abused Hersbach from when he was 11 years old until he was 18 at a house in Laverton in Melbourne's west during the mid to late 1960s. Although the physical abuse ended when Hersbach was 18, Rubeo's psychological hold over him continued until the younger man found the courage to confront the then 61-year-old priest in April 1994. But if Hersbach expected contrition from Rubeo, he got the opposite. "He just totally minimised it and said, 'What are you worried about, something that happened in the past', and it is not such a big deal." Soon after this confrontation, Hersbach told his wife about the abuse and reported Rubeo to the Melbourne archdiocese. As revealed by The Age today, the archdiocese's response to Hersbach's complaint was extraordinary. A priest, Father Frank Klep, who had just been charged with - and would later be convicted of - child sex abuse, was permitted by the archdiocese to be Rubeo's spiritual director. Rubeo, who did not deny Hersbach's allegations of abuse when confronted by senior church figures, was allowed to continue as pastor at the Boronia parish in Melbourne's outer east. His parishioners were not told about his alleged offences. Nor was Victoria Police. Hersbach's story encapsulates the range of experiences felt by many clergy abuse victims. It reveals a concerted effort by the church to harbour a paedophile priest. Indeed, the church's silence exposed children in Catholic communities unaware of Rubeo's history to a paedophile until December last year, when Rubeo died with 30 fresh abuse charges hanging over him. Despite having met Melbourne archbishops George Pell and Denis Hart to discuss Rubeo's acts and his desire for pastoral care, Hersbach remains bitterly disappointed by the archdiocese's handling of his case. "Despite all of this, I have still got a deep spiritual hunger but I probably don't look to the church or organised religion any more," Hersbach says, adding that not once in the 18 years since he reported Rubeo has anyone from the archdiocese inquired about his welfare. "I think there is a real sense of abandonment by the church in that regard," he says. HERSBACH first met Rubeo when he was in grade 5 at St Mary's Catholic School in Railway Street in Altona. The son of Dutch migrants, Hersbach had a tough, working-class upbringing in a housing commission estate in Laverton. His father had been deeply affected by his experiences in World War II and would often drown his problems in alcohol. His mother, a devout Catholic, missed her family in Europe. Rubeo was a charismatic priest in his early 30s who would tell jokes and play footy with local kids. He came to Hersbach's school seeking volunteers to become altar boys to assist with Mass. Hersbach and his twin brother Will put up their hands. Rubeo also ran a youth club each Friday night in a small hall near a temporary church in Laverton, not far from Hersbach's home. The priest would soon become a welcome visitor to Hersbach's house, helping the twin brothers with their homework. In 1964, Rubeo told Hersbach that he was going to buy a house in Laverton so he could be closer to him. Hersbach was 10 or 11 years old. Months later, Rubeo bought a house in Ulm Street, Laverton, just doors away from Hersbach. "It was about this time that Rubeo suggested that I do my homework at his house as it was a lot quieter," Hersbach told police in a 2011 sworn statement. Hersbach's first inkling that Rubeo was sexually interested in boys came when he was 11 or 12. After the Friday night youth club, Rubeo invited a small group of boys back to his home. "I remember that Rubeo gave us cigarettes and beer," Hersbach told police. "I remember that Rubeo would encourage us to swear at each other, he would laugh at us. I remember that he would tell us dirty jokes and then laugh at us … he suggested we play the Strip Jack Naked game." The boys and Rubeo stripped off their clothing one piece at a time until all were left in their underwear. Things went no further and the boys got dressed and went home. But Rubeo's behaviour would soon become more disturbing. Hersbach was in grade 6 when Rubeo first touched him sexually. His parents had begun to let him stay overnight at the priest's house. Nothing untoward happened on the first few sleepovers, but one night everything changed. "When I went to bed I was wearing pyjamas … at some stage during the night … I woke up to find Rubeo lying in the single bed under the covers with me. When I woke I felt Rubeo put his hand on my penis … I remember that he was rubbing my penis and testicles with his hand," Hersbach told police. "He grabbed my hand with his other hand and put it on his erect penis. My hand was directly on his penis, he moved my hand up and down with his hand … I didn't speak and I was pretending that I was asleep. "I remember the next morning nothing was said. Rubeo didn't acknowledge that anything had happened. I didn't say anything because I felt bad, I was ashamed and I didn't know what to think." This scenario was repeated frequently as Hersbach progressed through his teenage years. He and Rubeo were frequent visitors to a prestigious restaurant in Lonsdale Street called the The Latin. Rubeo would always order oysters and then go on to a pasta dish. Upon returning to Rubeo's house, the priest would fetch bottles of liqueurs and pour shots of Drambuie, Cointreau and Dom Benedictine for the 15-year-old student. After the drinks, what Hersbach describes as "the ritual" would occur. "I remember that we were both sitting on chairs and we began to take our own clothes off .. it seemed as though the alcohol was the trigger." Sometimes the pair would have intimate dinners at Rubeo's house on a Saturday night. The table would be set with a white tablecloth, fine china and wine glasses. "On reflection, I see he was almost having a date with me," Hersbach recalls. "I hated that stuff going on, I really did. But after a while I probably initiated it at times. No words were ever spoken during any of it and I could never look at his face." Perhaps Hersbach's most painful memory is not one of abuse but of Rubeo's early attempts to exercise control over his life by masquerading in public as his father. Hersbach was a talented junior footballer playing with the Footscray under-19s in the Victorian Football League. With his father working most Saturdays, it was Rubeo who would accompany Hersbach to his games. "He didn't wear his priestly garb, he just wore civilian clothes and everyone thought he was my father," he says. One day Hersbach's father did turn up and was standing in the outer when a team official noticed him. In front of teammates who all believed Rubeo was his father, the official pointed out Hersbach's actual dad in the outer. "I wanted to find a hole to crawl into because here was this priest masquerading as my dad. A true priest would have gone out there and brought him [dad] in and told the truth about who he was." Rubeo said nothing and let Hersbach drown in his own embarrassment. THE process that led to Hersbach meeting Gerald Cudmore, the Melbourne archdiocese's vicar-general, in August 1994 was hellish and drawn-out. The "big huge secret weighing me down" had caused Hersbach, by then a popular school teacher, to suffer serious bouts of depression and occasional outbursts in the classroom. File notes held by the archdiocese show that Cudmore (now deceased) asked Rubeo about Hersbach's claim and that Rubeo did not deny it. Told that Hersbach, at that point, did not wish to press charges, Rubeo admitted he had also abused Hersbach's twin brother during the same period in the 1960s. Neither boy knew the other had been abused until much later in life. Rubeo also hinted at another victim in a different area of Melbourne. The notes show Rubeo offered to resign. But his offer was not accepted and he continued to work in the parish in Boronia, with parishioners unaware of his criminal admissions to Cudmore. Astonishingly, Cudmore oversaw the appointment of Father Francis Klep as spiritual director to Rubeo in September 1994. At that time Klep was facing charges of child molestation and was convicted months later. However, his counselling role to Rubeo continued. Although Rubeo and Hersbach were both provided with counselling by the church, no disciplinary action was taken against the priest. Nor were police contacted by the archdiocese. A spokesman for the archdiocese admits the response, viewed by today's standards, was inadequate. HERSBACH is confident that Rubeo would have gone on working with unknowing parishioners if it were not for police receiving a sexual abuse complaint about the priest from an adult woman in 1996. Although he denied the woman's claim, Rubeo admitted to police a few instances of abusing the Hersbach brothers. As a result he was charged with two counts of indecent assault and pleaded guilty in October 1996. This represented a fraction of his sustained abuse of the Hersbach twins. Rubeo was given a two-year good behaviour bond. This time, the church accepted Rubeo's resignation. But it still did not tell his Boronia parishioners of his criminal acts. They found out only when a small article appeared in a Melbourne newspaper six months after his guilty plea. After the newspaper story appeared, the then parish priest wrote to two associated schools to inform them of Rubeo's court outcome. Rubeo retired with full benefits from the archdiocese's superannuation fund and moved to Portarlington on the Bellarine Peninsula. There is no evidence to suggest the Catholic community in the area was told of Rubeo's past. However, an archdiocese spokesman says "details of his convictions had received media coverage". Last year, detectives from the Knox police sexual offences unit travelled to Portarlington to lay 30 fresh abuse charges against Rubeo after taking several statements from the Hersbach brothers. Hersbach said he was told by one of the detectives that when they arrived they found Rubeo alone in his house with a 10-year-old boy. There was nothing to suggest the boy was being mistreated, but the thought of the boy alone with Rubeo horrifies Hersbach. "Whether he was being abused or not I'll never know, but I strongly suspect he groomed that family in the same way." On December 16 last year, Rubeo was to face a committal hearing in the Melbourne Magistrates Court on the 30 new abuse charges. It was a day for which Hersbach had waited more than 40 years. "Finally, the truth about Rubeo would come out … but the rug was pulled out from under our feet again," he says. At 10am on that day, a detective called Hersbach to tell him that Rubeo had died hours earlier from natural causes, aged 78. A few days later, one of Hersbach's children rang the Melbourne archdiocese to find out about Rubeo's funeral arrangements. Those details were never provided to the Hersbach family and no death notice for Rubeo appeared in any Victorian newspaper. The impact of Rubeo's abuse on Tony Hersbach has been immense. It has caused him severe mental health problems and cost him two successful professional careers and relationships with friends still connected to the church. "It's been heartbreaking to see how it has affected him," Lu Hersbach says. "The church needs to take full responsibility for what happened instead of duck-shoving it." The archdiocese spokesman says Hersbach has been offered and received support through the Catholic Carelink agency. He says Hersbach is welcome to contact the archdiocese to obtain further pastoral care. Despite decades of secrecy and anguish, Hersbach has survived when many others who have experienced similar abuse have not. He says he was moved to tell his story publicly when he saw the photographs of victims of clergy abuse who had taken their own lives on the front page of The Age last April. "I know if it wasn't for Lu and the kids I could be one of them," he says. Hersbach's advice to others who have suffered in silence is to do what he could not and talk to someone as soon as possible. "The hardest part is to not keep it secret."

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.