Where's "Father Manuel'? Police Hunting Fugitive Priest, Teacher Accused of Raping N.J. Teen

By Mark Mueller

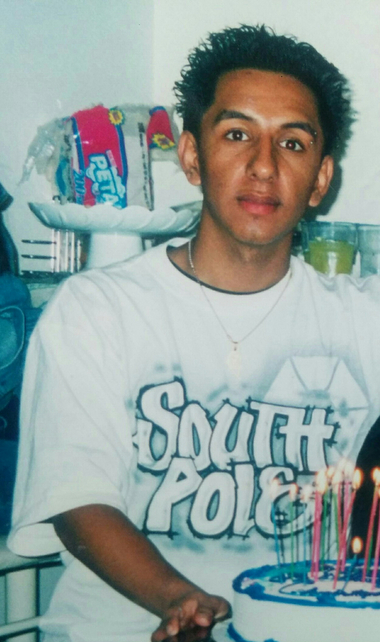

Twelve years ago, amid allegations he raped a 15-year-old boy in the rectory of a Plainfield church, the Rev. Manuel Gallo Espinoza vanished. The Archdiocese of Newark, where Gallo Espinoza had served as a visiting priest, said he apparently fled to his native Ecuador after church officials informed him of the claim and suspended him from ministry. Authorities never interviewed him. Within months, the investigation went dark. Now, with the filing of a lawsuit by his alleged victim and an examination by NJ Advance Media, federal and county authorities have expressed renewed interest in finding and questioning the 51-year-old priest. The NJ Advance Media investigation — drawing on law enforcement documents, public records and interviews — found that Gallo Espinoza obtained a visa to return to the United States in 2005. Three years later, unbeknownst to authorities in New Jersey, the man accused of raping a teenage boy took a job as a high school teacher in Prince George's County, Md., the inquiry found. Gallo Espinoza abruptly left the post in February of last year, a spokesman for the district confirmed. The spokesman, Max Pugh, said he could not disclose the reason for the departure because it was a personnel matter. Pugh said he was unaware of any allegation of sexual misconduct involving the former teacher. It's not clear where Gallo Espinoza is now. At his last known address — a block of modest one-and two-story homes in Lanham, Md. — neighbors said no one fitting his description lived at the house. One neighbor said she believed the home had been unoccupied for months. The Archdiocese of Newark, which found the accuser's rape allegation credible last summer, issued a public appeal in March for anyone with information about Gallo Espinoza to contact the Union County Prosecutor's Office. Later that month, two agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement visited Gallo Espinoza's alleged victim, asking about his account and showing him photographs of a man they believed to be the priest, who is not a U.S. citizen. Mark Crawford, the New Jersey director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, an advocacy and support group, said he was present at the meeting, held in a government sport utility vehicle outside the accuser's apartment building in Elizabeth. An ICE spokeswoman, Jennifer Elzea, declined to answer questions about Gallo Espinoza or say why the agents went to see the alleged victim. "As a matter of agency policy, ICE can neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation unless and/or until an enforcement action is pursued," Elzea said. 'Thank God I'm not dead' The priest's accuser, Max Rojas Ramirez, said he wants Gallo Espinoza to be prosecuted for the alleged assault, which he says set his life on a downward spiral from which he has yet to fully recover. New Jersey abolished the statute of limitations on sexual assault in 1996. "I want to see him in handcuffs," said Ramirez, now 28. "I've been through hell, and thank God I'm not dead, because I could be right now." NJ Advance Media does not typically name alleged victims of sexual assault. It is doing so in this case with Ramirez's approval.

He openly acknowledges previous problems in his life, including drug use, suicide attempts and several stays in psychiatric hospitals — issues he traces directly to the alleged rape. Currently unemployed, he said he wants to use his name and disclose his prior difficulties to show he has nothing to hide. Ramirez said Gallo Espinoza assaulted him in a bedroom at the rectory of St. Mary's Church in Plainfield just before Easter in 2003. Ramirez, then a member of the church's youth group, said he swiftly told his godfather, now a priest in Mount Arlington, and a second adult who served as the youth group's leader. Less than two weeks later, a representative of Catholic Charities in the Diocese of Metuchen reported it to the prosecutor's office, Catholic Charities confirmed. In that same time period, the archdiocese told Gallo Espinoza he could no longer serve as a priest because of a sexual abuse claim, said Jim Goodness, a spokesman for the archdiocese. Soon after, Gallo Espinoza was gone. Active investigation Mark Spivey, a spokesman for acting Union County Prosecutor Grace Park, said that as a rule, he could not discuss investigations involving allegations of sexual assault. A law enforcement official with knowledge of the case, however, confirmed the probe had been reactivated and said investigators would welcome new information about the alleged attack and the priest's whereabouts. The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the nature of the case, said the prosecutor's office conducted a thorough investigation 12 years ago but that it could not develop sufficient evidence to bring charges, in part because Gallo Espinoza fled before he could be questioned. Complicating the probe, the official said, Ramirez did not respond to requests for an interview, a contention Ramirez denies.

He said he continued to live with his mother in Plainfield until he was 19 and that no one from law enforcement reached out to him. He said he did not report the alleged assault directly to police at the time because another parishioner — a close friend of Gallo Espinoza — told then-teenage Ramirez he would go to jail for accusing a priest. NJ Advance Media is withholding the parishioner's name because he could not be reached for comment. Ramirez said he eventually reported the alleged assault to police himself in 2010, after he began to get his life together. Two years later, he approached the archdiocese with his attorney, Greg Gianforcaro, and was interviewed by the Archdiocesan Review Board, a panel that investigates claims of sexual abuse. In the summer of 2014, after considering Ramirez's claims and finding them credible, the board recommended Gallo Espinoza be dismissed from the priesthood, or laicized, said Goodness, the spokesman for the archdiocese. "We certainly don't think he should be in ministry, and we have cooperated with authorities here so they could find him," the spokesman said. A priest can be laicized only by the Vatican, and requests for laicization must come from a clergyman's home diocese. Goodness said Newark Archbishop John J. Myers recommended to his counterpart in the Diocese of Loja, Ecuador, last summer that Gallo Espinoza be defrocked. To date, Gallo Espinoza has not been laicized, though the Diocese of Loja has suspended his priestly faculties, Goodness said. The spokesman said the archdiocese did not know the priest had been working with students after he fled New Jersey. NJ Advance Media found Gallo Espinoza worked as a Spanish teacher at Parkdale High School from May 1, 2008, through Feb. 28, 2014. The public school, in Riverdale, Md., is a few minutes' drive from his most recent address. His employment was verified by birthdate and Social Security number. In addition, public address records show the same man once lived at the St. Mary's rectory in Plainfield. NJ Advance Media obtained a copy of his visa from the district through a public records request. The district's spokesman declined to comment on the rape allegation. As a rule, he said, all teachers undergo a criminal background check before they are hired. 'Looking for guidance' It began, Ramirez said, with confession. At 15, Ramirez said he was aboil with emotion, confused and ashamed that he had an attraction to men. The attraction was all the more tainted because, at age 8, a male cousin had molested him, he said. He thought speaking to a priest might help him sort out his thoughts. Gallo Espinoza, known to Ramirez as "Father Manuel," had come to St. Mary's a few months earlier, assigned there by the archdiocese after his arrival from Ecuador. He was not unfriendly, Ramirez said, but he was not especially talkative. Ramirez said he saw him mostly at youth group events, sitting in the back of the room and observing. When Ramirez decided to speak to a priest about his confusion, it was Gallo Espinoza sitting in the confessional, he said.

"I was looking for guidance and trying to figure out all these things, and eventually I came to tell him about the attraction I had toward guys," Ramirez said. "I told him what happened to me when I was younger. I had never told anyone about the abuse, and I thought it was the best place to tell it." The confession lasted no more than 10 or 12 minutes, Ramirez said. Gallo Espinoza, he said, offered no sage advice, telling him only to say a Hail Mary and pray on it. As Easter neared, the St. Mary's community prepared for an enormous Good Friday procession through the streets of Plainfield. Gallo Espinoza was to help lead it, with Ramirez, then an altar boy, at his side. A week before Good Friday, Ramirez said he was at the home of the youth group leader with other members when Gallo Espinoza called, asking to speak with him. The priest said he needed to see him in person, Ramirez said, and came to pick him up at about 10:30 p.m. Ramirez said he believed Gallo Espinoza wanted to go over their responsibilities for the upcoming procession. He learned otherwise when they pulled into the St. Mary's parking lot, he said. Gallo Espinoza chose a dark spot in the corner, then climbed out of the car and took a case of beer and a portable radio from the trunk, Ramirez said. Gallo Espinoza, he said, lit a cigarette, cracked a beer and began to unburden himself. "He started talking about how he doesn't feel good," Ramirez said. "He was telling me about people's confessions, about the things they've done, how he had a hard time listening to their crap. That's the word he used. He said he couldn't handle it anymore. He was depressed. He said he wanted to kill himself." There was another issue troubling the priest, Ramirez said. "He said somebody he knows in Ecuador is extorting him and wants to take his money," Ramirez said. "At that moment, he didn't say why. I'm sitting there thinking, 'What am I doing here? Why is he telling me all this?'" It was near midnight when Ramirez, exhausted, asked Gallo Espinoza to drive him home, he said. The priest refused, he said, insisting he spend the night at the rectory. Ramirez didn't call his mother. It wasn't unusual for members of the youth group to have sleepovers, and when he was with people from St. Mary's, his mother didn't worry, he said. Ramirez's father didn't live with the family. Gallo Espinoza, in a black shirt and white collar, led Ramirez in a back door, through the rectory kitchen and to a bedroom, the accuser said. Gallo Espinoza told him he would sleep in a different room, though he continued to pace in the kitchen and drink beer, Ramirez said. The teen drifted off. 'This is what God wants' It was the weight that woke him, Ramirez said. "I just felt something very heavy on top of me," he said. "It hurt. I was in pain. My eyes popped open, and he had his whole body on top of me. He started touching me and kissing me. I was shaking. I couldn't move. I couldn't talk." Speaking in Spanish, Gallo Espinoza told him everything would be OK, Ramirez said. "Don't worry," Ramirez said Gallo Espinoza told him. "This is what God wants."

He said the priest stripped him and began raping him. Ramirez said he then blacked out. It was morning when Ramirez awoke. Gallo Espinoza, he said, walked into the bedroom and matter-of-factly told him he wanted to give him a phone. "He says, 'With all the stuff I'm going through, you seem like a good guy to talk to,'" Ramirez said. The priest went on, Ramirez said, offering him a computer as well. Despite his fear and physical discomfort, the prospect of a phone and a computer excited Ramirez, he said. In a family of modest means, he had neither. Gallo Espinoza then drove him home, Ramirez said, stopping by briefly again later to deliver the phone. Over the next several days, Ramirez said, the import of what happened hit home. He slept through the weekend, he said, waking only to cry and eat. On Monday, April 14, he walked to the home of his godfather, Jeive Hercules, and told him everything, Ramirez said. Hercules, now an assistant pastor at Queen of Peace Church in North Arlington, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Ramirez said Hercules contacted the youth group leader, Antonino Salazar, and that the three drove to St. Mary's, where the two men confronted Gallo Espinoza in an office while the teen waited in the rectory, Ramirez said. When the three emerged, Ramirez said, Gallo Espinoza stared at him in fury. "He looked like he wanted to kill me," Ramirez said. "I was scared." He said Salazar then brought him to a Catholic Charities office in Bound Brook, where the teen told a priest and a nun he'd been sexually assaulted. Ramirez said the priest led him away and told him he was calling the police to report it. Terrified he would be arrested, Ramirez said, he fled the church and found his own way home. He said it was the only time he intentionally avoided police in connection with the Gallo Espinoza investigation. Ramirez said he does not, in fact, know if the priest in Bound Brook made the call that night. The record reflects that Douglas J. Susan, the compliance officer for Catholic Charities, notified the prosecutor's office of the alleged assault in a phone call and by letter on April 25, 2003, 11 days after Ramirez says he reported it to his godfather and the youth group leader. NJ Advance Media's efforts to reach Salazar for comment were unsuccessful. Authorities interviewed him through a Spanish-language interpreter in June of that year, according to a copy of his statement. In it, he said Ramirez told him Gallo Espinoza had "sexual relations" with the teen. Asked about Ramirez's demeanor when he made the claim, Salazar responded, "He was crying." Missed opportunities? It remains unclear how quickly Gallo Espinoza fled and whether his sudden departure could have been avoided. Goodness, the spokesman for the archdiocese, said Gallo Espinoza "just disappeared" without informing anyone. "I can't be specific in terms of time, but it was relatively soon," Goodness said. Asked if informing Gallo Espinoza of the allegation amounted to tipping him off, Goodness said the archdiocese followed protocols crafted by the nation's bishops in 2002 — the height of the clergy sexual abuse crisis — to strengthen protections for children. Under those protocols, a priest is to be removed from ministry as soon as an allegation is made, regardless of its authenticity. Priests are entitled to know in general terms why they are being removed. Crawford, the New Jersey director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, contends the prosecutor's office missed an opportunity to question Gallo Espinoza by not moving immediately to find him once the archdiocese reported the allegation. The advocate also criticized investigators for not doing more to look for the priest in the months after he fled and after Ramirez came forward to police in 2010, a period when Gallo Espinoza was teaching in Maryland. "It's a travesty of justice and a failure," Crawford said. "They should have been looking for him then, and they should be looking for him now." Ramirez said he, too, wants Gallo Espinoza to be located by police. He said he filed suit against the archdiocese, in part, because he hoped it could lead to information that might reopen the criminal case. The suit was filed in March. "What I want most is for him to be criminally charged," Ramirez said. "That was my intent from the start."

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.