|

Brendan Smyth's evil deeds can never be forgotten

By Liam Collins

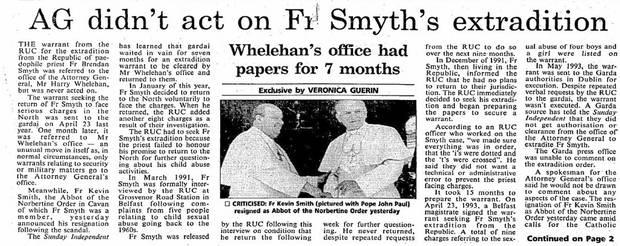

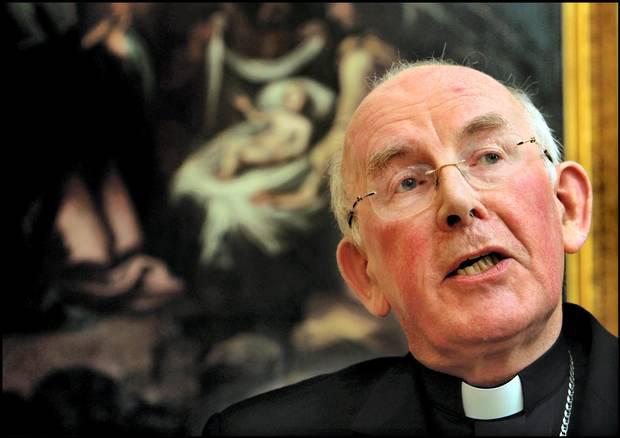

On the 20th anniversary of the serial abuser's admission of his crimes, Liam Collins retraces the scandal that shook Ireland to the top It is high summer in Kilnacrott, Co Cavan. Not even the ominous evergreen trees that surround the one-time Norbertine house and its small graveyard can darken this glorious summer's day. On a country road near the village of Ballyjamesduff, Co Cavan, there is a grotto to the left of the entrance gates, but the statue of the Virgin Mary has been "removed for maintenance" and a sign declares that this is now a 'Soul Sanctuary.' Ignoring a garish blue sign tacked to one of the trees declaring 'Private Grounds', I cross a stile and walk up the pathway to where the most notorious paedophile in the Irish Catholic church's sorry history of abuse is buried. Apart from the distant drone of a tractor saving hay, there is a stillness and silence that belies the harsh reality of one man's notorious life. Can you feel evil? Not on the short walk from the gate to the graveside. To the left, is the large modern complex bearing a white cross that the priests deserted in 2015, leaving the building now known as Holy Trinity Abbey and, to the right, a rectangular formation of graves. Each contains a headstone with the departed priest's vital religious statistics: Born. Vested. Professed. Ordained. Died. Between these milestones of their lives, many of these men probably did a lot of good, but all that has been destroyed by the man whose grave I came to see. It has no headstone, just an inscription in the polished dark limestone surround, with white crosses on either side inscribed: Brendan G. Smyth O.Praem 1927 to 1997 Rest in Peace This innocuous monument contains the last remains of a man whose image came to embody the horror perpetrated by his ilk on the innocent. A man who hid out here in the idyllic Cavan countryside and who, on this day, July 23, 1997, on the eve of his sentencing, finally admitted his "sins against God, offences against individual persons and offences against the laws of the Church". A month later, he died of heart failure in the Curragh prison. In the dead of night, his body was brought back to Kilnacrott and his fellow priests assembled in the church for Mass at 3.30am. Then, bathed in the headlights of the hearse, his coffin was lowered into this grave at 4.15am. Four gardai stood nearby in the shadows as dawn broke over the rolling countryside and Smyth was encased in concrete in his last resting place. In life, he not only desecrated those around him, but the ripples from his activities sullied the reputation of Cardinal Sean Brady and swamped the government of Albert Reynolds. Now, apart from the grave, all that remains of Brendan Smyth is the iconic image of him leering into the camera as he was led in handcuffs from the Central Criminal Court, a photograph that came to represent a scandalous era of clerical sex abuse. Born John Gerard Smyth in Belfast on June 8, 1927, he was ordained a priest in 1945, changing his name to Brendan when he joined the Norbertine Order, also known as the Premonstratensians. He was to receive psychiatric treatment over the years, but nothing would stop his rampage of sex abuse against young boys and girls. "Over the years of religious life, it could be that I have sexually abused between 50 and 100 children - that number could even be double or perhaps even more," he told one doctor. Perhaps even worse was that his crimes were known within his order and within the church in general. But he wasn't reported to the RUC (much of his early abuse was in Belfast) or the gardai. The Norbertine Order shielded and sheltered him, moving him to new parishes and different countries, knowing that he was a serial abuser, which allowed him to continue his appalling litany of crimes against children. One Norbertine priest, Fr Bruno Mulvihill, made attempts to alert the church authorities. But the order to which he belonged was independent of the Diocese of Kilmore and the senior churchman in Ireland, the Archbishop of Armagh. Although Cardinal Cahal Daly was privately furious about what he called the order's "incompetence", his successor Cardinal Sean Brady admitted in 1975 that, as a priest, he did his "duty" when he asked two victims of Smyth to swear an 'oath of silence' after testifying against him at a church inquiry. He said he did so at the behest of the then-Bishop of Kilmore, Dr Francis McKiernan. Arrested in 1991 by the RUC, Brendan Smyth fled across the border to Kilnacrott to await the next move in a game of cat and mouse. Like a lot of disasters, the seeds of Albert Reynolds' destruction began to emerge in two different places, but when they combined, it unleashed a political force that would topple the then Taoiseach. As if mirroring more recent events, it began with judicial appointments. Reynolds, for some unfathomable reason, decided to appoint Liam Hamilton as Chief Justice and Harry Whelehan, then the Attorney General, as President of the High Court. Determined to get his own way in the teeth of spirited opposition from his coalition partner Dick Spring, leader of the Labour Party, Reynolds' obstinacy led to a very public squabble between the two men, who were travelling in different parts of the world at the time. When they finally met, at Baldonnel Aerodrome in late September 1994, an 'accord' was reached to prevent an unwanted election, although Spring did not specifically agree to the appointment of Whelehan as President of the High Court. Simultaneously, journalist Chris Moore had put together a frightening documentary on Fr Brendan Smyth and the cover-up that allowed him to abuse with impunity. Broadcast on Thursday, October 6, 1994, the programme, Suffer Little Children, revealed among other things, that nine extradition warrants by the authorities in Northern Ireland had been lying in the Attorney General's office in Dublin unprocessed on the desk of a senior official, Matty Russell, for seven months. The Sunday Independent carried a front page story on the delay, written by Veronica Guerin, and as controversy raged about the issue, Spring's advisor John Foley told his coalition counterpart Sean Duignan: "The priest changes everything." At a Cabinet meeting on November 10, Reynolds forced through the appointment of Harry Whelehan as President of the High Court and Spring and his ministers walked out as the Government teetered on the brink of collapse. The days that followed were characterised by confusion in the Reynolds camp and hysteria in the corridors of power. There was a document "that will rock the foundations of this society to their very roots", claimed Labour minister Pat Rabbitte. "At the end of the day, when all other questions have been dealt with, one remains," Spring told an emergency meeting of his parliamentary party. "We have allowed a child abuser to remain at large in our community, when we had it in our power to ensure that he was given up to justice." As he furiously tried to save his government, Albert Reynolds told the Dail on November 15, 1994: "I must, today, explain the failure of a system in this specific case; a failure with ghastly and specific consequences for the children of the country. "I must not excuse the failure: I must ensure that it never happens again. "I will give this House a full and detailed report, but a full and detailed report of a failure in our method of dealing with such a crime as child sexual abuse will never and can never be satisfactory." He never got that chance. As the government unravelled, Labour Minister Ruairi Quinn told Reynolds: "We've come for a head, Harry's or yours, it doesn't look like we're getting Harry's." After his resignation on November 17, Albert Reynolds lingered in the Taoiseach's seat in the Dail chamber until almost everybody had shaken his hand in commiseration. Using a simple racing metaphor, he summed it up: "It's amazing, you cross the big hurdles and when you get to the small ones, you get tripped up." Nearing the end of his four- year sentence in Magilligan Prison, Smyth applied for parole. By now the case was getting the full attention of the Irish Attorney General, who successfully applied for Smyth's extradition to the Republic. In March 1997, he was flown from Derry to Dublin and stood trial on five specimen charges of child sex abuse at the Central Criminal Court. On July 23, he made a public apology to his victims in a hand-written statement read to the court by his counsel Gemma Loughran. On July 26, Judge Cyril Kelly asked and answered his own rhetorical question: "Is the defendant likely to re-offend?... in my view, yes," and sentenced him to 12 years in prison. Incarcerated in Arbour Hill Prison, Smyth was later moved to the Curragh in Kildare where he died of a heart attack on August 22 after collapsing in the prison yard. He was 70 years of age. Kilnacrott Abbey and its 43 acres of land was put up for sale in 2008 with a price tag of €3m, but apart from the timing, on the cusp of the property collapse, who wanted to buy a property which contained the grave of one of the most notorious paedophiles we have ever seen? Eventually, the estate was divided. The old abbey, a Tudor-Gothic building some of which dates from the early 1800s, is now The Cavan Centre, a "residential centre for education and community development" established in 1977. When you pass the entrance gates, it is clearly identified as private property "and not open to the public". A lay group calling itself Direction for Our Times, which has 400 prayer groups, including 35 in Ireland, paid €610,000 in 2012 for what is now called Holy Trinity Abbey, containing a large modern building, the graveyard and some surrounding land. It took over Kilnacrott as a "site of pilgrimage" in August 2015, when the Norbertines finally left. "The grave (of Brendan Smyth) can serve as a reminder for all of us of the enormous wounds of so many," the group's chaplain Fr Darragh Connolly was quoted as saying. "We do not feel that these wounds should ever be forgotten or dismissed." As long as Kilnacrott stands, that won't happen.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.