|

Settlement expected to affect diocesan services

By Seaborn Larson

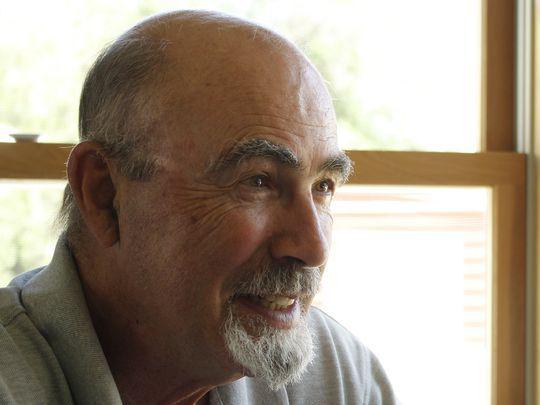

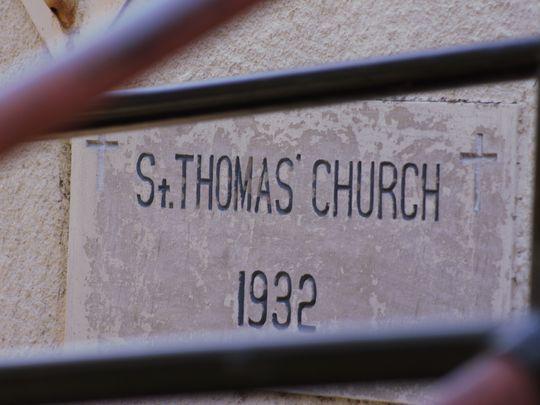

[with video] The Great Falls-Billings Diocese this month is working through the claim review and settlement process with victims alleging sexual abuse and their attorneys. Church officials believe the settlement won’t directly affect the parishes, although some are waiting to believe it until the final settlement amount is announced. Since the deadline to file a claim in the case, 86 people have come forward to enter claims of sexual abuse by priests, nuns and brothers, according to Vito de la Cruz, a Seattle attorney representing 38 of them. The dates of abuse range from 1947 to 1994. Attorneys for the victims say the Great Falls-Billings Diocese is the 15th to file for bankruptcy en route to settling with sexual abuse victims. Bishop Michael Warfel said before negotiations that the settlement will impose a loss of resources, and already has. “I used to have a person staffed in the office of worship, I don’t anymore, and I’m not planning on hiring anyone right now for that position. That would be an example,” Warfel said. "There would be a curtailing of some [services], realistically, until we get back on our feet." The Great Falls-Billings Diocese covers approximately 94,158 square miles, almost 64 percent of the state. The region contains approximately 400,000 people, 35,000 of them members of Catholic parishes spread throughout the region. Attorneys representing the victims say they don’t intend to seek a settlement that would financially sink the diocese. In a release on March 31, church officials say the diocese and its insurance carrier will both contribute to the settlement for the currently identified victims. There will be additional settlement funds also set aside for additional victims who come forward in the future. “Our goal has never been to break the diocese,” Cruz said when the diocese first filed for bankruptcy on March 31. “We know the church does good work in the most part. [The bankruptcy and settlement] can allow them to continue to do good work.” The diocese itself, according to federal bankruptcy documents filed March 31, listed total property value at about $20.7 million, between $13.8 million in “real property” and $6.9 million in “personal property.” No diocesan property has been sold to fund the settlement, but church officials stopped short of saying the move was out of the question entirely. The diocese also listed $3.2 million in total investments. Total liabilities are listed at $14.7 million. The diocese also writes in the filings that it is holding approximately $2.5 million in various cash accounts. The diocese doesn’t own that $2.5 million, but is holding it in trust, storing it or borrowing it. Parish contributions have varied some each year, coming in at $9.4 million at the end of the 2015 fiscal year and $6.2 million at the end of 2016. "What I've experienced when I go out to the parishes, they're operating pretty much as normal," Warfel said. "In terms of what we offer as a diocesan office, I think certainly there's going to be less than we've been able to do in previous years." What long-term effects the settlement will have on the diocese remains to be seen, said diocesan attorney Greg Hatley. The whole point of the bankruptcy filing, he said, is to allow victims, the church and their attorneys to work toward a settlement fund the diocese can survive through. “While it’s in the process, obviously we can’t answer those questions,” Hatley said. “That’s why we’re engaged in this transparency in the effort to go through this process; so that we’re in a position to emerge from it, not only in a conciliatory fashion as it relates to the abuse survivors and dealing with them, but also to put the diocese in a viable financial situation so that we can continue forward with our good works for the current and future Catholics in eastern Montana.” The parishes across the eastern half of Montana, however, should not be heavily affected, Warfel said. Parishes fund the local church through donations, events and bake sales. In Billings for example, two church properties, the Holy Rosary and Our Lady Guadalupe, have both been approved by a federal bankruptcy court judge for sale. The proceeds won’t go toward the settlement, but instead toward a new church to replace them. Meanwhile, the new K-8 St. Francis School, tagged at $18 million, is set to open this fall, and the St. Thomas the Apostle Church project, another $4.5 million, is also nearing the project’s end. Crews this summer also put some work into the St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Harlem, built in 1932. Ralph Schneider, bookkeeper/treasurer for the Harlem parish said the community and the Catholic congregation, many of them lifelong members, supports the parish’s projects like this one. “Those types of things we pay for,” Schneider said. “It’s not the money we collect from the parishioners. It comes from church bazaar-type things. That’s how small communities survive.” What the settlement payments may affect, Schneider said, is the Care and Share payments the diocese receives from each parish. The diocese uses the Care and Share, which is reassessed each year, to pay for continuous outreach services. “If we get a traveling priest, that’s paid for,” Schneider said. “They use it for outreach to the poor and for the kids.” The Care and Share currently sits at about 25 percent of the parish’s income, Schneider said. That assessment could see a hike in order to fill in the gaps created by the settlement process. But Schneider hasn’t seen any sign of that yet, five months after the bankruptcy filing. “We’ll find out about the next assessment,” Schneider said. Jim Stang, a California attorney for a committee of victims representing the 86 at settlement negotiations, said in July it’s difficult to guess where the Great Falls-Billings Diocese settlement will land by comparing with previous settlements spurred by similar allegations. The Helena Diocese settled with more than 360 victims for about $20 million, while the Oregon Province of Jesuits shelled out $166 million for nearly 500 victims. Schneider was somewhat frustrated by the lack of action by the church to eradicate clergy and laypeople accused of sexual abuse; he was frustrated for everyone involved. “It’s kind of shooting yourself in the foot because you choose to ignore it,” he said. “It’s really tragic. It’s tragic for the individuals raped and abused, the communities it happened in. It’s tragic that the diocese chose to ignore it.” The settlement comes at a time when the parish is shrinking, as are revenues. Schneider, 70, said he’s one of the youngest members of the Harlem church, which sees about 15 people on average. “There are no young children in the church anymore,” he said. “The youngest one just graduated high school. The writing’s on the wall for us,” he said. “You won’t have enough people going to church to keep it open.” Schneider said there are simply no jobs to anchor families in the community; pretty much the same story illustrated by small towns around Montana and the country. The businesses in Harlem, like the grocery store and lumber yard, are bolstered by the traffic coming through en route to Havre. The Fort Belknap community three miles away plays a big role in that, he said. The Catholic Church in Harlem won’t be marred by a past of harboring priests accused of sexual abuse; Schneider won’t let it. Each parish receives a copy of court documents sent to the diocese regarding the lawsuit filed containing more than 70 victims, but Schneider usually throws them all away. When approached by the Tribune, he wasn’t aware that Rev. Edmund Robinson, one of the most abusive priests publicly accused of abuse, was a predator. Instead, Schneider wants to stay focused on keeping his parish afloat. He said the simple costs of paying the light bills could spell the end, but that doesn’t mean anyone is less encouraged to attend each service. Schneider joined the church in the 1990s and carries on just like the rest of the congregation who have lived their lives congruent with the church values, not swayed by the "few bad apples” who cloaked themselves there. “We’re naturally optimistic,” he said. “We just keep doing it.” Contact: slarson@greatfallstribune.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.