|

She accused a Mishawaka priest of sexual abuse. She got Bishop Rhoades' attention.

By Caleb Bauer

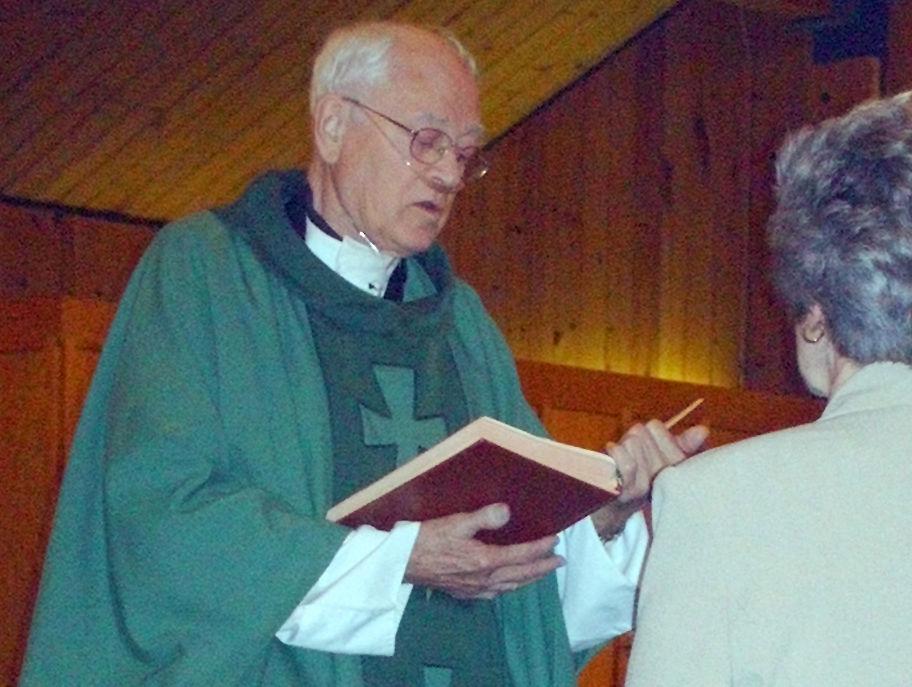

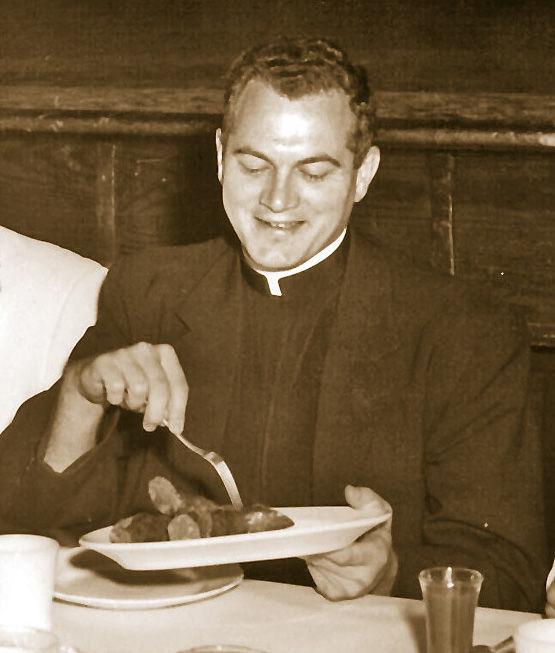

When Bishop Kevin Rhoades announced his plan to release names of priests in the Fort Wayne-South Bend Diocese accused of abuse, he said the revelations of rampant abuse in Pennsylvania weren’t the only factor in his decision. He also credited a woman who had reported sexual abuse to the diocese — and had urged him to release the name of her abuser. “I was so conflicted,” Rhoades said at a news conference Friday. “She was asking me to release the name. So to be honest, this whole issue of releasing names is something that even before the Pennsylvania grand jury report I’ve been considering.” Carolyn Andrzejewski-Wilson watched the live broadcast of the news conference on her computer at her North Carolina home. She knew Rhoades was talking about her. Almost two years ago, the former Mishawaka resident met with Rhoades to relay her story about abuse at the hands of the Rev. Elden Miller, a former priest at St. Joseph Church and Queen of Peace Church in Mishawaka. She urged Rhoades to publicly release all credible accusations against Miller and to be a “trailblazer for transparency.” Even though Andrzejewski-Wilson met with Rhoades nearly two years ago, the bishop didn’t announce his plan to release accused priests’ names until after the allegations in Pennsylvania became public; Rhoades’ handling of two cases in that state were included in the grand jury report. Andrzejewski-Wilson is not sure Rhoades would have acted if not for the Pennsylvania controversy. But she doesn’t want to question his intent. She focused instead on her decision to come forward, which she says was inspired by The Holy Spirit. “All of a sudden, I felt like I had this courage, that it was time to talk,” she said in an interview from North Carolina. Andrzejewski-Wilson was not the first person to accuse Miller of abuse. The diocese has found abuse allegations from four people against Miller to be credible, including Andrzejewski-Wilson, according to the diocese’s victim assistance coordinator, Mary Glowaski. Miller died in 2008. Andrzejewski-Wilson, 63, says the abuse began in the 1960s, when her grandmother cooked and cleaned at the rectory at St. Joseph. She was 6 when she was first abused. Over the next five years, she said, Miller sexually abused her “more times than I can count,” at both her grandmother’s house on Main Street and inside the church rectory. “When we were growing up … everyone thought Father Elden Miller was so wonderful,” Andrzejewski-Wilson said. “He could do no wrong.” She suppressed memories of the abuse for years, fearing church officials wouldn’t believe accusations against the popular Miller. She didn’t tell her family either; Miller was often a guest for dinner at her grandmother’s home. Finally, after she turned 11, Andrzejewski-Wilson confronted Miller and told him to stop, which he did. She continued living in Mishawaka and South Bend, working as a social worker, and eventually married and had two kids. Twelve years ago, she moved to North Carolina to be closer to one of her four grandchildren.

Revealing her story

Andrzejewski-Wilson filed an official report with the Fort Wayne-South Bend Diocese in September 2015. She said a spiritual director at her parish in Charlotte helped her find the courage to come forward. In June 2016, Andrzejewski-Wilson sat down with Rhoades. She brought photos of herself from ages 6 through 11, placing them in front of the bishop. In addition to pushing for transparency, she said, she also urged the bishop to work to change Indiana’s statute of limitations for child abuse. Under the state’s laws, charges cannot be filed after a victim turns 31. Andrzejewski-Wilson initially worried about a “David versus Goliath” situation with the Catholic Church, but she credits Rhoades, Glowaski and others at the diocese for taking her accusations seriously. Andrzejewski-Wilson says she has forgiven herself for not stepping forward earlier. She felt guilty for staying quiet in 1998, when she learned Miller would help re-open a school at Queen of Peace Church. “When Queen of Peace started the school, I got sick. I started throwing up,” Andrzejewski-Wilson said. “I thought ‘My God, they’re future survivors.’ and I couldn’t forgive myself for a long time for not talking about it then.” She says she is sharing her story now to give fellow survivors of priest sex abuse the confidence to contact the Church and law enforcement authorities. In the Fort Wayne-South Bend Diocese, allegations of priest abuse are directed to Glowaski or Vicar General Rev. Mark Gurtner. Glowaski gets in touch with the accuser, helping them reach a decision on whether to file an official report. “We understand that trust of us comes at a terrible cost for them,” she said. “We’re asking them to trust someone who’s part of this institution.” Once a report is made, Glowaski notifies Rhoades and Gurtner, and the diocese begins investigating the allegation and notifies law enforcement in cases where the priest is still alive. Then, victims are offered a sit-down with Rhoades, and the diocese may cover certain needs, such as counseling and medical costs. “Most of the allegations that we receive are with priests that we (already) have multiple allegations against,” Glowaski said. “There could be times when I’ll speak with someone for months before they make an official report.” In the case of Miller, Glowaski said she couldn’t discuss details of the three other people who have credibly accused him of abuse because, unlike Andrzejewski-Wilson, they haven’t given her permission to speak publicly. But she confirmed that a plaque at Queen of Peace School honoring Miller was recently removed. Now that she has finally revealed her story, with a receptive audience at the diocese, Andrzejewski-Wilson hopes to inspire others to step forward. “This isn’t about me anymore,” she said. “I just want survivors to realize there is help, and I hope that one more survivor may finally have their voice back.” Contact: cbauer@sbtinfo.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.