|

Survivor’s story: daughter of a Saint says she was abused by priest

By Kim Chatelain

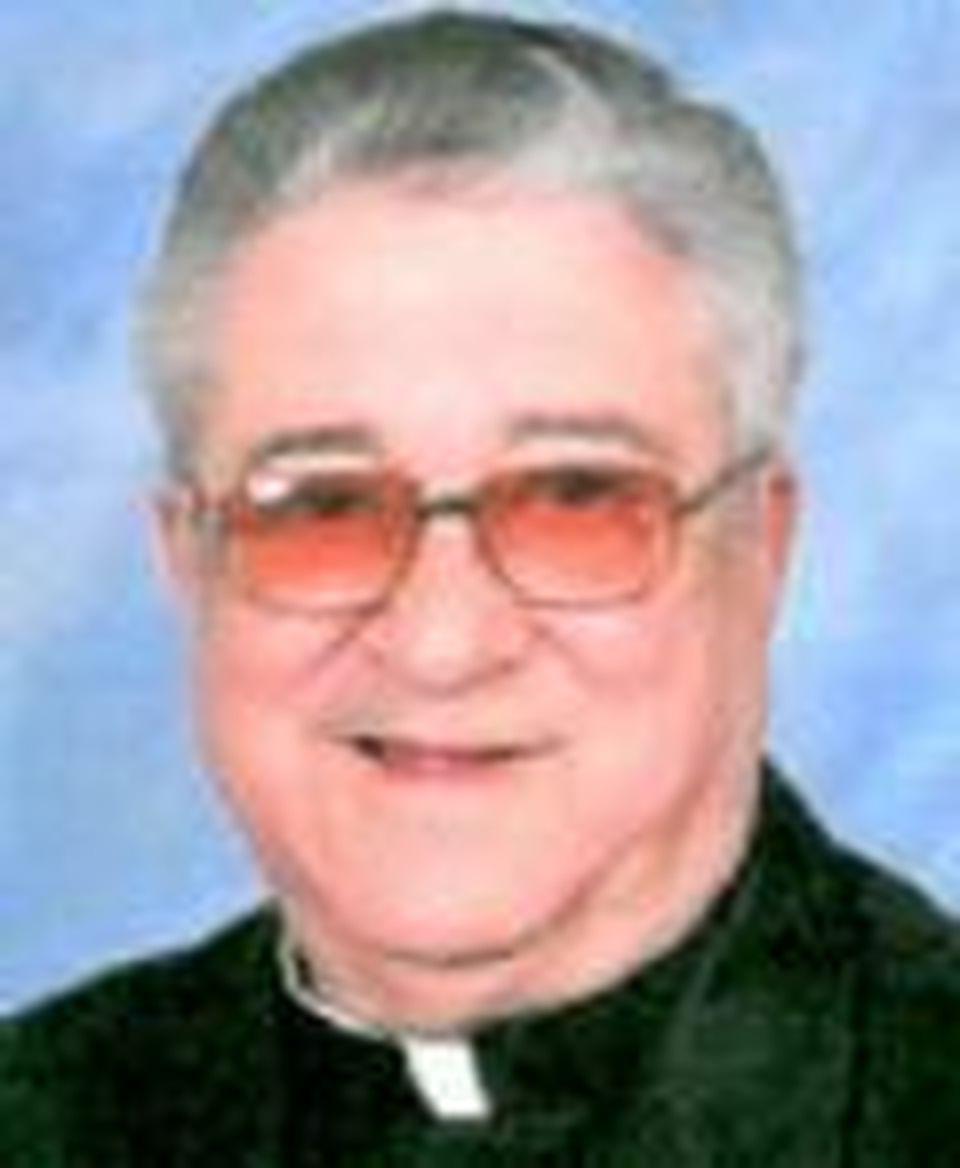

Linda Lee Stonebreaker says she was four-and-a-half years old when a Catholic priest picked her up at a preschool in River Ridge and sexually assaulted her in his car. The year was 1968, long before clergy abuse in the world’s largest Christian church entered the public’s consciousness, and before Stonebreaker was old enough to fully understand the gravity of what she says happened. Confused and intimidated by the priest, Stonebreaker says for years she told no one. She feared she wouldn’t be believed, would go to hell for revealing the abuse or would bring about an attack on the priest by her father, Steve Stonebreaker, then a 6-foot-3, 235-pound linebacker for the New Orleans Saints with a well-documented penchant for fisticuffs. She says she repressed the memories until her father’s suicide in 1995 caused images of the molestation to resurface and prompted her to call authorities to file a complaint against the priest. After law enforcement authorities told her the statute of limitations for a criminal case had expired, Stonebreaker once again buried the nightmarish thoughts. In 2014, Stonebreaker said, other difficulties in her life once again dredged up memories of the sexual abuse. “I really needed to get help,” she said. Having moved to California, she said she reached out to the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which referred the case to the Archdiocese of New Orleans. The New Orleans archdiocese said its victim’s assistance coordinator launched an investigation, as per its policy. The archdiocese, in a statement, said it confronted the clergyman, who “vehemently” denied the incident. He lapsed into a coma and died about three months after the archdiocese received the complaint and before the case was vetted by an independent lay review board. The panel, which is chaired by a psychiatrist, is tasked with determining whether allegations of abuse are credible. “There was no finding of a credible allegation since the matter had not yet been presented to the Independent Review Board,” the archdiocese’s said in a statement to NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune. “There are no other allegations of abuse against this priest during his ministry.” The priest in question served in the diocese for more than 50 years and retired as a monsignor. Since 2014, the Archdiocese of New Orleans has “continued to provide pastoral care and counseling to the person who made the complaint as is our policy,” according to the statement. Stonebreaker said that care includes weekly visits to a therapist in California. Stonebreaker, 54, said she has “tremendous gratitude” that the archdiocese did not ignore her complaint and is paying for her therapy. But she wonders if she is really the clergyman’s only victim, or if others are simply reluctant to step forward, as she was for so many years. She’s telling her story, she said, in hopes it may help others. “I know I’m not special,” said Stonebreaker, who recently posted on social media a brief description of the incident and the name of the priest she said abused her. “I know that pedophiles don’t strike just once.” The archdiocese did not name the accused clergyman. In a Facebook post Oct. 17, Stonebreaker identified him as Louis P. LeBourgeois and called on the archdiocese to publicly name him. On Nov. 2, the archdiocese released the names of 57 clergy members who it says have been “credibly accused” of molesting minors over many decades. LeBourgeois was not among those listed. Stonebreaker’s story illustrates a growing debate over the recently released of list of abusive priests in New Orleans and across the United States and the difficulties involved in identifying credible abusers. While releasing the names answered calls for transparency and is viewed by many as a step in the right direction, some critics question whether other pedophile clergy members have managed to avoid public exposure under an internal review system whose parameters were set by the same institution that had for decades provided cover for abusers. ‘I have a duty to speak up’ LeBourgeois was born August 23, 1935, in New Orleans, attended Our Lady of the Rosary elementary school and received his secondary education at St. Joseph Seminary north of Covington and Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., according to his obituary in The Times-Picayune. He was ordained into the priesthood June 3, 1961, and – according to the archdiocese – has an unblemished clerical record. During the 1960s and early 1970s, he served at an associate pastor at St. Charles Borromeo in Destrehan, St. Matthew the Apostle in River Ridge and St. Agnes in Jefferson. He was pastor at St. Peter Church in Reserve from 1975 to 1983 and held the same position at St. Christopher the Martyr in Metairie from 1983 to 1990. LeBourgeois was the state spiritual director of the Catholic Knights of America and served as chaplain of the Jefferson Parish Fire Department. On July 18, 1988, he was awarded the Prelate of Honor, signaling his rise to the position of monsignor. He retired to the North Shore and continued to celebrate Mass at various churches in western St. Tammany Parish, doing so with a portable oxygen tank near the end of his life. He died July 1, 2015. He was 79. The obituary characterized him as a stalwart proclaimer of God’s teachings. The New Orleans archdiocese was the first in the state to release names of accused clergy members. Other Louisiana bishops are contemplating whether or when to release such lists. The Archdiocese of New Orleans responded to inquiries from NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune about Stonebreaker’s case, but its statement redacted the clergyman’s name, in part because the case had not been evaluated by the review board, it said. Stonebreaker said she has nothing to gain financially by making the disclosure. She said victims need to confront such issues to find healing and offenders need to be held accountable. She decided to speak out after reading recent media accounts of an August report from a Pennsylvania grand jury that chronicled clergy abuse and systemic coverup in six Catholic dioceses in that state. The report named more than 300 priests credibly accused of sexually abusing more than 1,000 child victims over decades. Her allegations also come at the height of the #MeToo movement, which has prompted many women around the world to share stories of sexual abuse they’ve held secret for many years. “I have a duty to speak up,” Stonebreaker said. ‘I was so scared’ In 1968, Stonebreaker attended a preschool near her family’s River Ridge home. One late spring afternoon while her mother was home with the flu, Stonebreaker said, the school’s owner arranged for her to get a ride home with Le Bourgeois , who happened to be at the child care center. Although she recognized the priest from St. Matthew Church, where her family attended Mass, Stonebreaker said she was reluctant about getting a ride from him. Her family had schooled her to never get into a car with strangers. Because she was not fully potty-trained and wearing “big girl underwear,” Stonebreaker said she was afraid to have an accident while in the car. “I remember being very nervous,” she recalled. The priest told her to get into the front seat and drove away from the preschool. Stonebreaker said he eventually told her to move closer to him and he reached his hand between her legs and began to molest her. At first, Stonebreaker said, she thought he was checking to see if she had had an accident. But eventually he asked her, “This feels good, doesn’t it?” As he drove around River Ridge, apparently taking a circuitous route to her family’s home while molesting her, Stonebreaker said she recalls him stopping at a stop sign and waving to someone working in a front yard garden. She said the priest eventually exposed himself and made her put her mouth on his penis. Because she had brothers, Stonebreaker said she knew - even at age 4 - the basics of the male urinary system. “I was so scared he was going to pee in my mouth,” she said. As she cried, Stonebreaker said, Le Bourgeois told her, “I’m only doing to you what other men will do to you in the future, only I’m doing it first.” “All I wanted to do was get out of the car,” Stonebreaker recalled. The priest eventually drove to her family’s home. Before she got out of the car, Stonebreaker said he told her, “If you tell anyone, God is going to send you to hell. If you tell your mother or father, they won’t believe you.” As she entered the house, Stonebreaker said she screamed to her mother, “Why didn’t you come and get me?” But she didn’t tell her mother what had happened. Stonebreaker said that was the only time the priest touched her, although she remembers seeing him at her home not long after the incident. She said she doesn’t know why he was there, but during his visit she remembers LeBourgeois quietly telling her, “Remember, don’t tell.” For years, she didn’t. ‘It all came rushing back’ An aptly-named football player if ever there was one, Steve Stonebreaker was selected in an expansion draft by the New Orleans Saints in 1967. Initially reluctant to relocate to Louisiana from Baltimore, where he had played for the championship-caliber Colts and had a thriving insurance business, Stonebreaker eventually gave in and became a member of the original Saints team. He and his wife settled with their five children into a two-story home on Dart Street in River Ridge, about a half-mile from St. Matthew the Apostle Catholic Church. The 1967 Saints were a rambunctious, colorful collection of rookies and veteran cast-offs known more for their collective personality than their 3-11 record. Sporting a macho surname and an aggressive style of play, Stonebreaker quickly got a reputation for getting involved in fights – once being fined $1,000 for blindsiding Giants center Gregg Larson after a game. Endearing himself to Saints fans, Stonebreaker later remarked the fine was the best money he ever spent. After his career with the Saints ended in 1968, he stayed in the area and ventured in various businesses, including stints as publisher of a Saints tabloid called “Grid Week” and as owner of Stonebreaker’s Restaurant on Edenborn Avenue in Metairie. On March 28, 1995, Steve Stonebreaker was found lying on the floor of his garage at the Dart Street family home, inches from a vehicle’s exhaust pipe. His death was ruled a suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. The late Peter Finney, the legendary sportswriter for The Times-Picayune, paid tribute to Stonebreaker in a column, calling him “the most original of the original New Orleans Saints.” While Steve Stonebreaker became a sports celebrity in New Orleans, he had become a larger than life figure in his daughter’s life. His suicide coincided roughly with the fourth birthday of Linda Lee Stonebreaker’s oldest daughter. The combination had a profound impact, she said. “Knowing that my daughter was at the age that I experienced the assault had really hit me,” she said. “After his death,” Linda Stonebreaker said of her father, “the floodgates opened. It all came rushing back. I could remember everything.” Having moved to California at age 24, Stonebreaker said she decided to seek therapy to help her cope with the flashbacks she was experiencing. It was then that she decided to report the incident to authorities. She said she called the New Orleans District Attorney’s Office and the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office [MT6] and was told the case was too old to investigate. She also put in a call to the Archdiocese of New Orleans to find out if LeBourgeois was still a priest. A woman answering the phone told her he was no longer Father LeBourgeois, but rather Monsignor LeBourgeois. Stonebreaker said the news shocked her. Not only was LeBourgeois still a clergyman, but he had been promoted. “I got scared. I put it down and left it alone,” she said. She got on with her life, which included two marriages and four children. In 2014, Stonebreaker said she began having personal relationship problems that therapists told her were related to childhood experiences. It was then that she reached out to the Catholic Church hierarchy. After telling her story to the victim’s assistance coordinator in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, Stonebreaker said, a formal investigation was opened. She said Jacquie Ruiz, a California-based private investigator and former FBI agent, was assigned the case. Contacted recently, Ruiz said she was not at liberty to discuss the Stonebreaker case and referred questions to the Archdiocese of New Orleans. Stonebreaker said Ruiz found her allegation credible and made plans to fly to New Orleans to interview LeBourgeois, who had denied the incident in the early stages of the investigation. But before Ruiz could make the trip, LeBourgeois was hospitalized with pneumonia and eventually slipped into a coma, according to Stonebreaker and the Archdiocese of New Orleans. A few weeks after LeBourgeois died, Stonebreaker said she received call from the New Orleans archdiocese and was told the investigation was being closed. She said she was told that hers was the only complaint against the longtime clergyman. ‘It’s a long journey’ The issue of clergy abuse has gradually been uncloaked over the past several decades. The revelations began with the wrongdoings of the Rev. Gilbert Gauthe, a priest in the Diocese of Lafayette who in 1985 was convicted of sexually abusing as many as 39 young children. Other scandals surfaced over the years, leading up to the 2002 Boston Globe reports into clergy abuse and coverup that prompted criminal prosecutions of five Roman Catholic priests and brought the issue of sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy under a national spotlight. The August report by the Pennsylvania grand jury, and recent revelations in other countries, have reignited the crisis in the church over the abuse and the hierarchy’s efforts to hide it. Catholic leaders have said the vast majority of offenses outlined in the explosive Pennsylvania report occurred before preventative measures were put in place by the U.S. Conference of Bishops in 2002. The "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People" established guidelines to prevent clergy abuse. It has been updated three times since 2002. New Orleans Archbishop Gregory Aymond has said there have been no credible reports of clergy abuse in the local archdiocese in more than a decade. In releasing the names of the credibly accused clergymen, the archbishop said he did so “for the sake of the victims, the survivors, for their healing, for our transparency and to pursue justice.” But Aymond said he hesitated releasing the names because many of the accused are now deceased and cannot defend themselves. According to the organization that runs BishopAccountability.org., dozens of the nearly 200 dioceses in the U.S. have released lists of priests accused of abusing children in past decades. Stonebreaker feels strongly that all dioceses should release the names of accused priests, a move that may allow survivors of such abuse to come forth and lighten the burden they have been carrying. Now a semi-retired massage therapist, Stonebreaker said she shared the story of her abuse with her mother decades after the incident and has since shared it with other family members, friends and those involved in the investigation. Letting it out has proven helpful for her, but Stonebreaker wonders how many others are living with pent-up memories that they’ve been unable to share or have been reluctant to report. “I have had treatment constantly and I’ve been on a journey of healing,” she said. “But it’s a long journey. I want to help other people take a healing journey.” Contact: kchatelain@nola.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.