Catholic Church Still Breaking Its Own Laws, 16 Years after Priest Abuse Scandal Exposed

By Candy Woodall

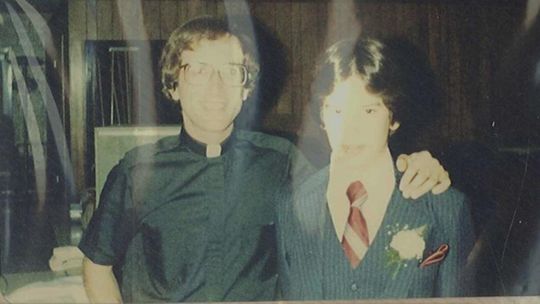

In 2002, bishops decided that accused priests removed from ministry could no longer practice mass publicly or be known as priests. But family, friends and neighbors knew the accused Rev. Thomas Scala only as “Father Tom.” When some of his neighbors were asked by a reporter earlier this year if they knew Thomas Scala, they said “no.” But when asked if they knew a priest who lived at Scala’s address, they frequently said, “Oh, yeah! That’s Father Tom.” Scala had been accused of sexual misconduct with three children while he served as a priest in York County in the 1970s. He died in October at the age of 71 in Florida, where his neighbors believed he was a retired priest. They did not know about the allegations against him. The Diocese of Harrisburg might have removed Scala from ministry – though it won’t say when – but it demonstrated no oversight to ensure Scala was not still acting as a priest, even if he wasn’t practicing in a church. “We are not an agency that would track predators or registered sex offenders like that,” diocese spokesman Mike Barley said during a September interview with the York Daily Record. Scala went to St. Michael’s in Clearwater for Christmas and Easter masses, which are two of the busiest days of the year with the pews packed with families. Parishioners had no idea Scala was accused of child sex abuse. They had no idea he was anything more than a retired priest who was safe to be around, according to the Rev. Sylvester Taube, a priest in the Archdiocese of Detriot who was a friend and neighbor of Scala's in Florida. Taube believes Scala celebrated mass alone at his home most of the time, but can’t be sure. Taube was in Detroit for at least half the year, if not longer. The Harrisburg diocese was trying to laicize Scala, who was fighting the process that would have stripped him of the priesthood, a paycheck and insurance provided by the church. It was a “complicated” process and could take years, Barley said. Scala was recognized as a priest to the time of his death in October. His obituary used the noble title of reverend. “The hope is these situations don’t happen again,” Barley said. It’s not just the Harrisburg diocese. Other than the formal Prayer and Penance program and facility used by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, the York Daily Record determined there is no plan in place in any diocese in Pennsylvania or those contacted in other states to monitor for defrocked priests who might still masquerading as priests in good standing. Prayer and penance: More than 78 predator priests in Pa. still paid by Catholic church It’s nearly impossible for any diocese to track the whereabouts and constant actions of priests banned from ministry. Such men cannot practice in a church operated by a diocese, but the church cannot control whether the priest acts like a trusted minister in good standing to lure more victims. This very scenario is why some archbishops in 2002 claimed the prayer and penance program was better than defrocking to make sure abusive priests didn’t have access to children. Rules set at Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2002

Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory was president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2002 and led what he described as a successful meeting in Dallas. He said the policy changes meant there would be “no free pass, no second chances, no free strike” for priests accused of abuse. In 2014, Gregory was caught in a scandal of a different kind. Parishioners in his Atlanta diocese were outraged when they learned he used part of a $15 million donation to the church to build a $2 million archbishop’s estate. He ultimately sold the home after living in it for three months, despite his vow of poverty. He gave himself a second chance, as he is still serving as the archbishop in Atlanta. Of the policies passed in Dallas, York Daily Record reporting has shown that the following are not be followed in in multiple dioceses: Any priest who has ever abused a minor will be permanently removed from ministry Accused priests are barred from celebrating mass publicly Accused priests are banned from presenting themselves publicly as priests Accused priests can only celebrate mass privately and lead “a life of prayer and penance” The church must adopt practices of “transparency and openness” in responding to the public and media Of the 196 dioceses in the U.S., only half have come forward with lists of abusive priests, according to Terry McKiernan, president of BishopAccountability.org, a watchdog site that tracks abusive clergy.

Of the 301 priests named in Pennsylvania's landmark grand jury report this year, many were identified as respected clergymen in their obituaries and more than 78 are still on the church payroll. And laicization, the process that officially removes a priest from the priesthood, has been a slow process. It requires approval from the pope himself. Without any legal path to justice in several states because of expired statutes of limitations, abusive priests who were kept hidden by the church for decades are automatically granted a second chance. And in 2002, some bishops thought that was fair. Bishop Thomas G. Doran, who served in Rockford, Illinois in 2002, said church canon law was older than the U.S. Constitution and superseded it. “When we do this, we rat out our priests, and I’m not in favor of doing that,” he was widely quoted as saying at that time. Doran retired in 2012. Several other bishops thought the policies were too tough on priests and ignored the Catholic principles of forgiveness. Bishop John T. Steinbock, who served in Fresno, California, until he died in 2010, said credibility was a concern. Accusations, he said, could come from “some crazy person, which we all have in our dioceses.” Some bishops agreed with him and objected to automatically reporting all allegations to law enforcement, claiming the church should decide whether the allegations are credible. Ultimately, bishops in 2002 passed the new policies by a vote of 239-13. One of the most supportive voices was that of Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua, who served as archbishop in Philadelphia.

Catholic leaders needed to support the new policies to reassure parents that their children would be safe and so “our faithful, without any embarrassment, will be able to say, ‘I’m proud to be a Catholic,’” he said. But some of the thinking that existed then is why lawyers, victims and experts believe rules are still being broken today. “The church has proven it can’t police itself and set its own rules. We continue to see that in the thousands of priests being named and the thousands of victims coming forward,” said Mitchell Garabedian, an attorney who has represented abuse survivors since before the Boston scandal broke in 2002. More questions than answers The level of self-policing in the Catholic church, and the slow-moving state and federal investigations into priest abuse make it difficult to assess how well the following policies are being implemented: All dioceses are required to check backgrounds of staff in contact with kids A priest’s record must be fully reported to a diocese where he’s being transferred No confidentiality agreements Transparency and openness in dealing with the public and news media Annual public reports on safe environment programs Every diocese reaching out to every victim to offer counseling and other services Dioceses are not subject to Right-to-Know laws that would compel them to make evidence of those policies publicly available. State and federal investigators can look into those things through lawsuits, but that information can take years to reveal.

Victims say they don’t trust information coming out of dioceses today and that they were not contacted by dioceses to receive counseling and services. “The only calls I’ve had about my well-being are from Attorney General Josh Shapiro and his staff. They’ve called at 9 p.m. on a Thursday before just to say, ‘How are you?’ To me, that is incredible,” said Michael McDonnell, a leader with the Philadelphia chapter of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. “How can we allow the church to police themselves? Their best thinking got us to where we are today,” he said. James Faluczak is both an abuse survivor and a priest who left ministry because he “couldn’t stand the system anymore.” He served in the Erie diocese for 18 years until 2002. In that time, he said he was told by four diocesean officials not to share abuse information with the district attorney. One of the reasons Faluczak is sure the problems continue today is because of who’s still in power. “Bishops today all say their predecessors were the problem, but all these men were in positions of power when it was going on. They were immersed in it. You don’t become bishop today without the Catholic church being able to trust you, even if the victims don't,” he said.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.