|

| Credibly Accused

By Matt Grubs

Santa Fe Reporter

February 6, 2019

https://www.sfreporter.com/news/coverstories/2019/02/06/credibly-accused/

Jim Field loved going to church.

As a kid, he remembers waking for morning mass.

"The sun might just about be coming up. And I'd get in the bathtub, I'd clean myself up, I'd hop on my bike and ride to Sacred Heart Church in Farmington," he says. "And I would sit and wait for mass. I just loved being there."

It was around 1960 and the service, he recalls, was in Latin. He didn't understand a word, but something about the ceremony—the quiet, the reverence—resonated with him.

He was 8 years old, getting ready to turn 9 in 1961, when the abuse happened. It was summer. Father Conran Runnebaum, a Franciscan priest, had only been a cleric since 1955. Farmington was his second assignment, starting in 1958.

Field is not sure how many times the priest abused him. Once for sure. Maybe three times, he thinks.

"Conran had me pull down my pants and he pulled up his habit, like a cassock," Field begins. He had no idea what was happening.

"How would I know what was going on? Except, I do remember at one point, enters Miguel … and he's horrified," Field says of another priest, Miguel Baca. Horrified—but also the same man who would later expose himself to, and further abuse, Field.

"I have a memory of later, in the bathroom, which you accessed from outside the church in those days … but it was in that bathroom where those …" Field trails off.

It would be 40 years before the memories, in terrifying flashes, started to come back to him. "My knees went weak and I fell to the floor and began to sob and cry. … It was like lava in a volcano coming up through me," he says.

After he worked up the courage to report the layers of abuse, the Diocese of Gallup investigat

Runnebaum, who died in 2007, is on the list of "credibly accused" priests, brothers, seminarians and laity compiled by the diocese during its bankruptcy proceedings. Baca, also dead, is listed, too.

Both men served for decades not just in Gallup, but in the Archdiocese of Santa Fe. Neither is on Santa Fe's list of abusive priests.

In November, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe filed for bankruptcy protection and reorganization. Its decision to keep the two priests—and potentially scores of others like them—off its public list raises questions about Archbishop John C Wester's stance on making public the painful history of priestly sex abuse as the church faces a legal reckoning with survivors of such crimes.

The archdiocese refused to provide anyone to answer questions from SFR. It sent a brief statement in response to SFR's inquiry, denying it had received any allegations against Conran Runnebaum or Miguel Baca "occurring within the archdiocese and thus we cannot discuss these names any further." It ignored further requests for an interview.

But bishops in New Mexico's other two dioceses in Gallup and Las Cruces have made the decision Wester in Santa Fe has not: Both of their lists of abusive priests and church leaders include the names of men who have been credibly accused elsewhere and have served in the New Mexico dioceses.

"Basically, it helps with being more transparent," says Suzanne Hammons, communications director for the Diocese of Gallup. "Anybody who's a potential survivor … it might give them the courage to come forward."

Attorneys and survivors who spoke to SFR about the decision say abuse victims are often reluctant to speak out for fear they won't be believed. Seeing a name on an official church list can help them, and help the church realize a full accounting of the damage done.

That's especially important in a place like the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, which will soon have a federal bankruptcy court set a "bar date," after which abuse survivors aren't guaranteed their cases will be considered. In dioceses that have significant assets, funds have been set up for survivors who come forward after the bar date. It's unclear if Santa Fe will have such a fund after bankruptcy.

The debate over which priests to include on lists of credibly accused clergy—and even what the term "credibly accused" should mean—is one that's playing out right now in the Catholic Church. Pope Francis recently ordered the US Conference of Catholic Bishops to delay sex abuse reforms until he meets with leaders from world bishops' conferences later this month in Rome.

The Roman Catholic Church is at once hierarchical and monarchal. Total authority is vested in the Holy Father at the Vatican, who tells tens of thousands of cardinals, bishops and priests what to do, and instructs hundreds of millions of lay Catholics on how to interpret God's word.

While there's a hierarchy for priests, once they become bishops, they have near total authority over their diocese. The only person, in effect, who can tell a bishop definitively what he must do is the pope.

The takeaway here in New Mexico is that bishops in Gallup and Las Cruces can't tell the archbishop in Santa Fe what to do any more than they can tell Pope Francis how to run the church. Nor can Wester tell those bishops how they must behave.

The Archdiocese of Santa Fe defines credibly accused to mean "the allegation of abuse could reasonably have occurred."

The church investigates allegations—though it's also supposed to report them to police—and a bishop-appointed review board offers advice on whether allegations are credible. But bishops have the final say.

Merit Bennett was one of the first attorneys in New Mexico to sue the Catholic Church over abusive priests in the 1990s.

"It's a moving target … 'credibly accused,'" he tells SFR. He says the church's arbitrary definition isn't something that binds the legal system. "We're dealing with kids. [Survivors] who were raped when they were kids. … We don't know a fraction of the extent of this."

Brad Hall's Albuquerque law firm has sued the archdiocese on behalf of victims dozens of times. "The logic of the list is to provide notice," says associate attorney Levi Monagle.

"Victims find their validation frequently in these lists," Hall explains. "If they're abused by Runnebaum or Baca and don't see either of their names … that can be the difference between someone who comes forward [and someone who doesn't]."

READ THE LIST OF CREDIBLY ACCUSED PRIESTS FROM SANTA FE, LAS CRUSES AND GALLUP.

It's how some survivors realize that what happened to them was abuse, the attorneys say. And given the number of priests who have decades of abuse charges in the Catholic Church, it's likely at least some of the men who served in the Archdiocese of Santa Fe without an accusation here still committed a crime.

"Trying to mediate this public access to the truth is something they've lost the right to, in my opinion," Monagle says.

Hammons, with the Diocese of Gallup, says there's no national standard within the church for determining what accusations are credible. And even if the bishops could agree on something among themselves, she says, "The pope is the only one who can come in and say, 'You have to do this.'"

After a stunning report from a Pennsylvania grand jury last year chronicled decades of systematic abuse and cover-ups by the Catholic Church, New Mexico was among the states to begin its own investigation. Attorney General Hector Balderas' inquiry isn't done yet, but spokesman David Carl signaled the office's dissatisfaction when SFR asked about the archdiocese's choice to exclude priests like Runnebaum and Baca from its list.

"Failure to provide accurate information, including an accurate accounting of credibly accused clergy, is inappropriate and only serves to delay justice," Carl says in an email.

At the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, all of SFR's inquiries were met with sighs and frustration. "The church has no business doing this," says Michael Norris, a member of the organization's national board of directors.

Norris says he went to the church in 2001 with his accusations about a priest in Louisville, Kentucky. The diocese there told him he didn't need to worry about a priest who was much older now than when he committed the alleged crimes. His sex drive, Norris says the church told him, wasn't what it used to be.

"I sat there for 12 years until another victim came forward," he tells SFR.

Former SNAP president David Clohessy is equally as skeptical about the church's efforts.

"Bishops continue to do the absolute bare minimum. And they don't put out complete lists because they don't have to," he says. "As long as bishops can split hairs, they do."

Field, who lives in an old farmhouse in Warren County, Indiana, is on the phone. A block away from SFR—and probably audible to him on the connection—the bells from the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi peal away.

As he talks, Field gets so focused on what he's saying or remembering that he doesn't seem to hear questions. He just plows on, determined to get through what took him decades to talk about.

"It's very disturbing that these leaders—you know, the archbishop and Father John, the vicar general—can't understand why it would be important to list these pedophile priests on their website as credible allegations," he says.

A decade ago, angry, hurt and craving acknowledgment, Field decided to sue Gallup.

|

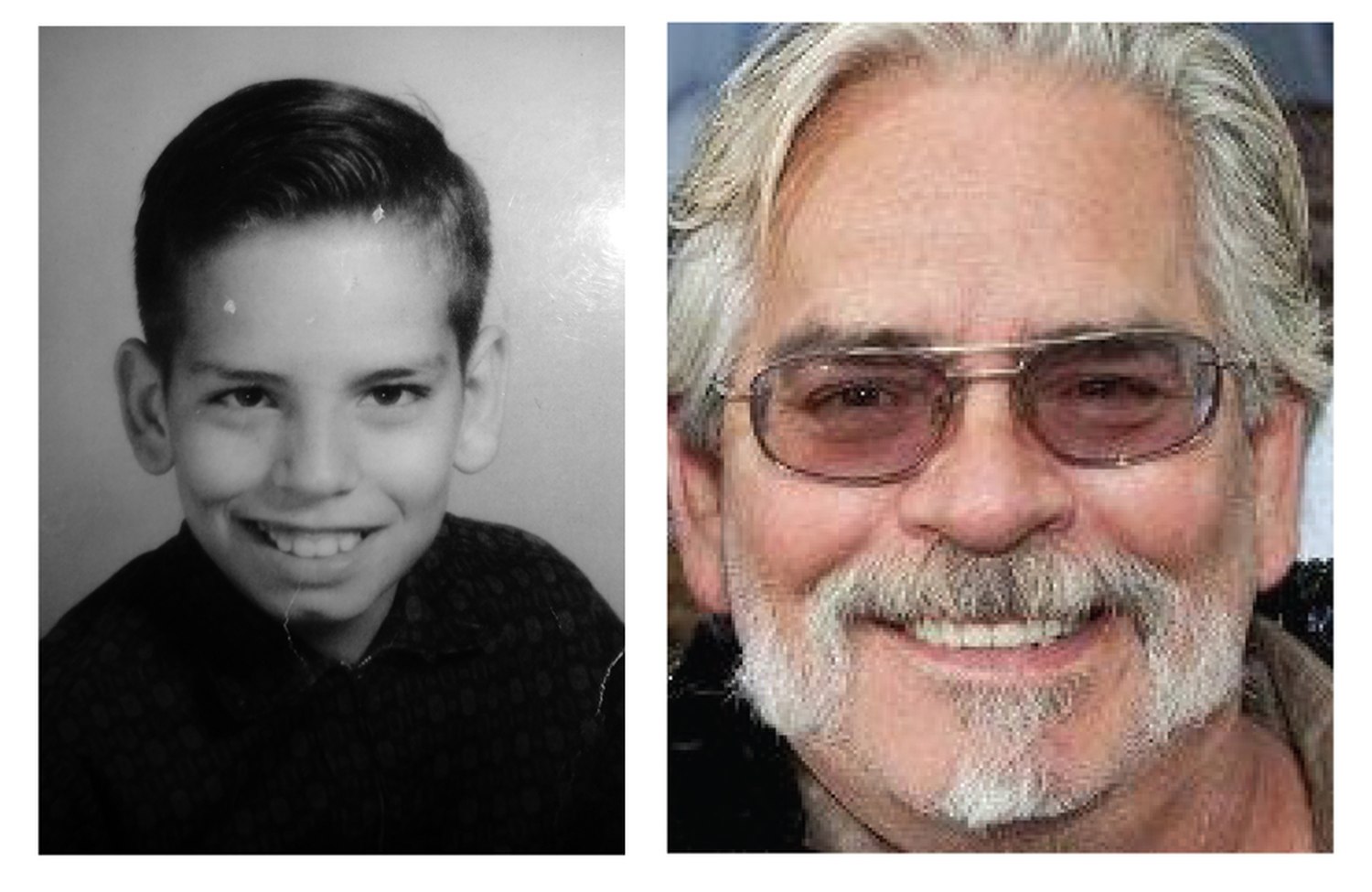

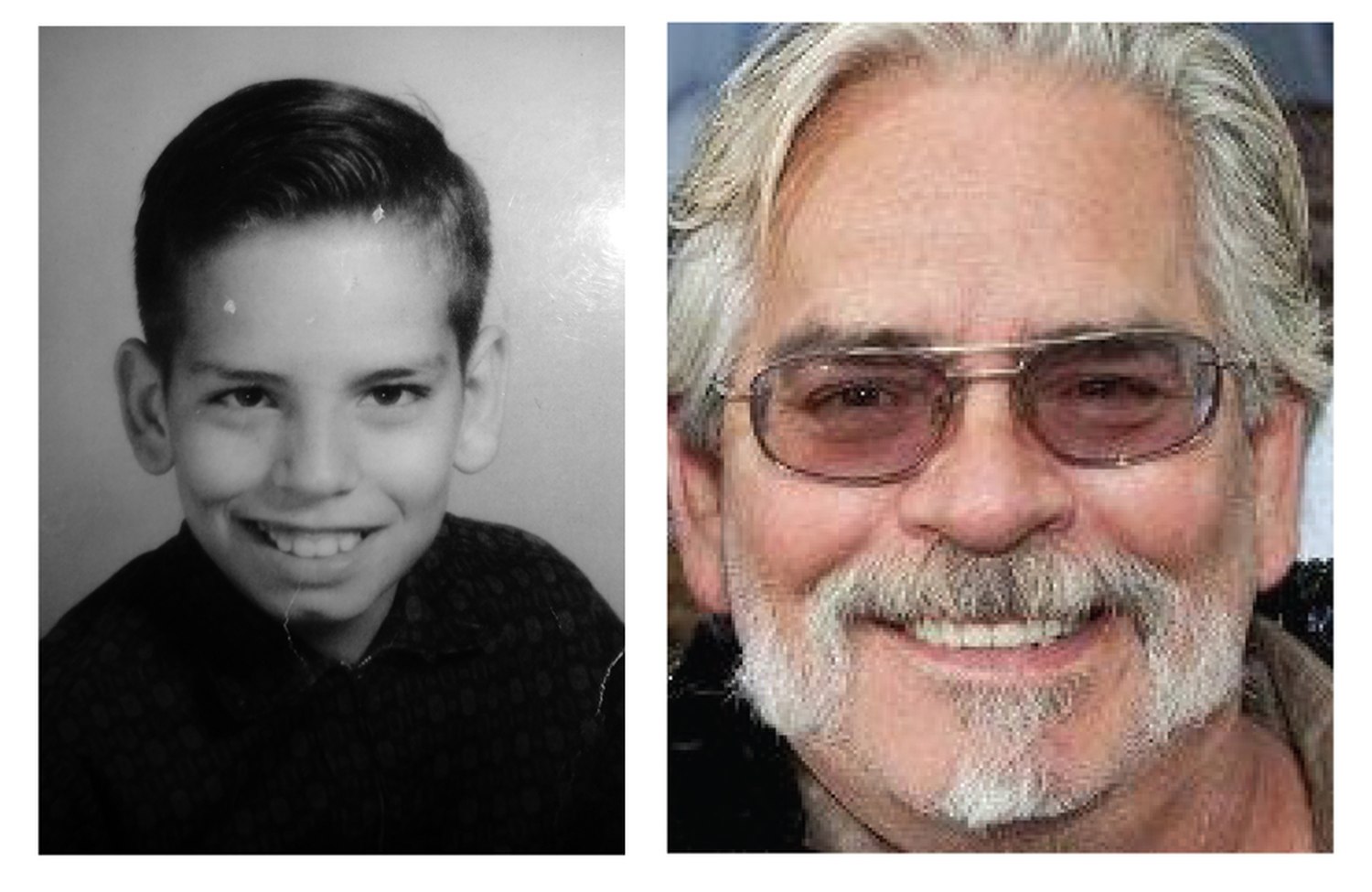

Jim Field says he first recalled his abuse some 40 years later as he listened to a morning news show in the early 2000s interview with a survivor of priestly sex abuse in Boston. | “It’s taken years,” Field says about coming to grips with the abuse. “And to this day I realize how it gravely, gravely affected my adult life.” | Courtesy Jim Field | Courtesy Jim Field

|

"The story checked out. I did our research. There had been credible complaints about particularly Runnebaum and Baca in the past," recalls his attorney, Jeffrey Trespel. The diocese settled before Trespel had to file a suit. The amount is confidential.

"[Runnebaum and Baca] had been shifted around to a number of parishes," Trespel says. "And of course they usually stuck them in poor, rural places where nobody was going to say anything; where the church had a lot of sway."

By 1980, Runnebaum was in the Archdiocese of Santa Fe. A Farmington Daily Times article from May of that year has him returning to Sacred Heart for a special mass. He also served at Our Lady of Belen parish. A 1991 church history that's still alive online today reports Runnebaum's assignment there as "youth oriented." His obituary says he served in Pojoaque and Arroyo Seco. Santa Fe Archbishop Michael Sheehan presided at his funeral in 2007.

Baca traveled around frequently and appears to have served in San Fidel, near Grants, with Runnebaum for a time. He led spiritual retreats and eventually served in the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, too. Newspapers show Baca traveling frequently in and out of archdiocesan territory.

Kathleen Holscher, the endowed chair of the University of New Mexico's Roman Catholic Studies program, says situations like Baca's present a particular problem for the church in tracking abusive priests. "That story is a very familiar story," she tells SFR. "That actually shows up in the Pennsylvania grand jury report."

Father Edward Graff is the man she's talking about. He was a priest in Allentown, Pennsylvania, who "raped scores of children," according to the report. After decades there, he came to the now-shuttered Servants of the Paraclete rehabilitation center in Jemez Springs. Dozens of pedophile priests passed through the facility and into parishes around the archdiocese, including Graff in the 1980's. He continued to abuse children, and was eventually caught in 2002 in Texas.

"He's not on the archdiocese's list either," she says.

Bishops and archbishops have to be dedicated to getting the full picture, she says, and willing to expend resources to do it.

Referencing another diocese's list, though, wouldn't seem to cost much.

Holscher thinks the number of men who might fall on an archdiocesan list of those credibly accused elsewhere could be "at least dozens of priests, if not hundreds."

Trespel says the archdiocese has no excuse.

"I think they're obstructing justice. I think they are playing games with their parishioners and with the public at large," Trespel says. "They have a duty to disclose those priests with credible allegations, wherever in the world they are."

All these years later, Jim Field still goes to church.

READ RESPONSES FROM SANTA FE CATHOLICS

On a recent Friday, he postpones another phone call to honor a commitment to help the priest at the local parish set up for eucharistic adoration, a ceremony in which Catholics worship, pray and meditate in front of communion materials—bread and wine.

"I love my church," he says.

Sometimes, he says, other parishioners or priests will notice his willingness to help and say he's special.

He's heard that before—at Sacred Heart, from the priests who abused him.

"I was very special, and they would tell my parents that they were sure I would grow up to become a priest," he remembers. Ever frank, he says it gives him the creeps: "I don't want to be special. I just want to be ordinary."

Jim Field has spent a lifetime trying to come to grips with a faith that refuses to die, and the church in which it was so grievously harmed. Even in his darkest times, he says, he would kneel and say the prayer of St. Francis.

|