An Oft-accused Priest, One Victim's Story and the True Meaning of Bankruptcy

By Sean Kirst

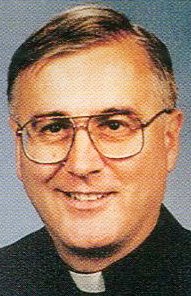

The word has a new imperative for the Buffalo Diocese, which last week sought federal court protection after 260 men and women filed lawsuits over the past six months under the state’s Child Victims Act, alleging they were abused by Catholic clergy or staff in Western New York. Yet Michael Eames, 60, has his own definition of bankruptcy. He learned it as a teenager, he said, through the behavior of a priest Eames describes as "a wolf." Eames is one of 15 men who have filed Child Victims Act lawsuits maintaining they were abused as youths by Donald Becker, now 77 and living in retirement in Florida. The sheer number of CVA allegations against Becker, who has never faced criminal charges, dwarfs those of any other priest from greater Buffalo, living or dead. Diocesan officials have said they removed Becker from active ministry in 2003 because of credible evidence of abuse. They reached a settlement with another Becker accuser even before the Child Victims Act process began. According to court documents, the diocese is not providing Becker with any legal help against his accusers. “The decision to provide legal counsel to individual priests is decided on a number of factors and on a case by case basis," Greg Tucker, a diocesan spokesman, wrote in an email. "In the case of Rev. Becker, he is not being provided counsel.” Becker, for his part, has publicly denied sexually abusing children. "No, I did not," Becker told Dan Herbeck of The News, in 2018. "Certainly not sexual. … This is quite shocking."

He stopped serving as a priest, he told Herbeck, because of Parkinson's disease. Contacted recently, Becker said he has been asked by his lawyer to decline all comment. To Eames, an admission from Becker would at least give all these survivors an element of healing that once seemed impossible: Utter, unequivocal vindication. “He’s ruined a lot of lives," Eames said. "There has to be some sort of judgment.” His description is similar in many details to several of the accounts involving Becker, who served at nine Western New York parishes between 1968 and 2002. Eames recalled that when he was about 14, after his freshman year in the mid-1970s at St. Francis of Assisi High School in Athol Springs, a friend told him of a Hamburg priest who occasionally allowed teenagers to drink. Eames remembered Becker from attending school at SS. Peter & Paul. He and his buddy began stopping by the rectory. Becker, he said, would sometimes hand them a beer, even in the presence of other priests. Before long, Eames said, he was part of a group of teens who casually traveled with Becker to his cabin at Java Lake. They drank freely, Eames said, and did jobs around the property. His mother – without knowledge of the alcohol – was always thrilled when Becker called, “thinking I was being put into good hands,” Eames said. A day arrived, Eames said, when none of his friends were around. Becker asked if he wanted to go to the cabin, do some work and then stay the night. To Eames, it seemed "a totally safe" adventure, a teenage getaway. At the cabin, he said, Becker brought out some beer and a bottle of whiskey. Eames, with little knowledge about drinking, began mixing the two and drinking fast. Before long, he said, he was blackout drunk. The next thing he remembers, he said, was waking up in the morning – head throbbing, in his pajamas, amid the smell of vomit – while Becker was sexually assaulting him in bed. Overwhelmed, Eames pulled away and put on his clothes. He struggled through doing some more work on the property before Becker drove him home. Sick and distraught, Eames thinks now he would have broken down and told his parents if by chance they had seen him as he walked in. “My dad was at work and my mom was busy,” Eames said. In his room, stunned and ashamed, he vowed never to mention to anyone what happened. Becker kept calling the house, and Eames said he ducked the calls. “I tried to shut it out,” he said. He blamed himself for the assault, furious that he allowed himself to be so vulnerable, self-loathing he found himself unable to dismiss. “It kind of put me into almost a limbo, struggling with what had happened and who I was," he said. "I kind of lost some years there from the pure shock and that has kind of followed me through life.”

Eventually, his first marriage collapsed. “I was depressed and I didn’t know why,” Eames said. He married again but could not break the downward spiral, often weeping – seemingly for no reason – in front of his wife, Lynda. Finally, a day came in 2006 when he simply made a choice. He told his wife everything. Her support, then and now, was a major step toward ongoing recovery. A friend directed him to Catholic Charities, where a counselor offered help. Eames said he wrote a letter about Becker to the diocese, which led to a meeting with auxiliary Bishop Edward Grosz. When asked about Becker, Eames said that Grosz replied: “He is doing a life of penance.” Eames received treatment for depression from therapists and psychiatrists, provided by the diocese. He became a regular at Buffalo-area meetings of SNAP, or Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. He soon met others who had their own stories about Becker, only intensifying the questions Eames still asks today. When did the diocese first hear these allegations, and why was the priest for so long allowed easy access to youths? “Becker," Eames said, "had left a trail of broken young men.” He has tried, as best he can, to repair damage in his life. Years after their divorce, Eames called his first wife to explain why he struggled. He wishes now he had confided in his mother and father, who had no way of understanding what must have seemed to be a chain of self-destructive choices. “My parents went to their graves thinking I was a screwball,” Eames said. Two years ago, Norbert Orsolits, a longtime diocesan priest in Buffalo, admitted to Jay Tokasz of The Buffalo News that he abused “probably dozens" of children. That statement upended decades of diocesan secrecy. A year later, the approval of the Child Victims Act created a window for survivors to go to court.

Eames had already taken part in a diocesan "reconciliation and compensation program," rejecting a settlement he saw as inadequate. He hired William Lorenz Jr. of the HoganWillig firm to handle his case. "The Child Victims Act," Lorenz said, "restored power to survivors." While Eames is appreciative of counseling obtained through the diocese, he said he had no options within that arrangement. His life was turned upside down by a priest whose predatory actions, he contends, were tolerated for too long. Eames is going to court to seek a reckoning for what he calls “45 years of being lost.” He wonders, like hundreds of others, how bankruptcy will affect his case - and any potential revelations. Albany Bishop Edward Scharfenberger, now serving as apostolic administrator in Buffalo, has said repeatedly that he believes real transparency is the only way to build regional trust. Last week, responding to a question about Becker, he told The Buffalo News' editorial board that an open airing of such a searing history might be a place to start. "Certainly, you can take a case as you mentioned like Donald Becker," Scharfenberger said. "We could certainly take isolated cases where there was particular egregious 'actings out,' take a look at that and examine those records, and make some sort of accounting for that." While Eames waits, he contemplates a fundamental understanding. At least 16 men, some of retirement age, say they were assaulted by the same Catholic priest. Many have spent years trying to find their way to consolation, fearing they somehow brought this pain upon themselves. To Eames, all that suffering reaffirms one point. At 15, in a way Eames said he cannot forget, a man he trusted illustrated what bankrupt really means. Sean Kirst is a columnist with The Buffalo News. Email him at skirst@buffnews.com or read more of his work in this archive.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.